One needn’t support the recently-enacted tax legislation to be disturbed by the tenor of much criticism of it. Many opponents, and indeed some press reporting, took for granted that if one voted for a significant tax cut after having expressed longstanding concerns about federal deficits, one must be an irredeemable hypocrite. But lower taxes and smaller deficits can coexist.

Some examples of the criticism: Neera Tanden wrote in NBC news of the “staggering hypocrisy” inherent in passing “shameful tax cut legislation” after sponsors had previously warned of a “forthcoming debt crisis.” Robert Schlesinger opined in US News & World Report that the legislation suggested “an incredible case of cognitive dissonance or simple breathtaking hypocrisy and/or duplicity.” Ezra Klein fumed at Vox that lawmakers who supported the bill were “nihilists.”

This refrain was repeated on editorial pages nationwide: you could be for deficit reduction, or alternatively you could be for tax cuts. Only a nihilist hypocrite could possibly have taken both positions.

Beyond its closed-mindedness, this outpouring of indignation was all premised on a mistaken foundational assumption. It is entirely possible to be for both lower taxes and smaller deficits. In fact, I would argue this was not only possible but that it represented the most responsible policy position given the projections lawmakers faced when the tax bill was debated. (Disclaimer: the following should not be misinterpreted as necessarily an endorsement of the specific tax legislation, nor of prioritizing tax relief over fiscal consolidation).

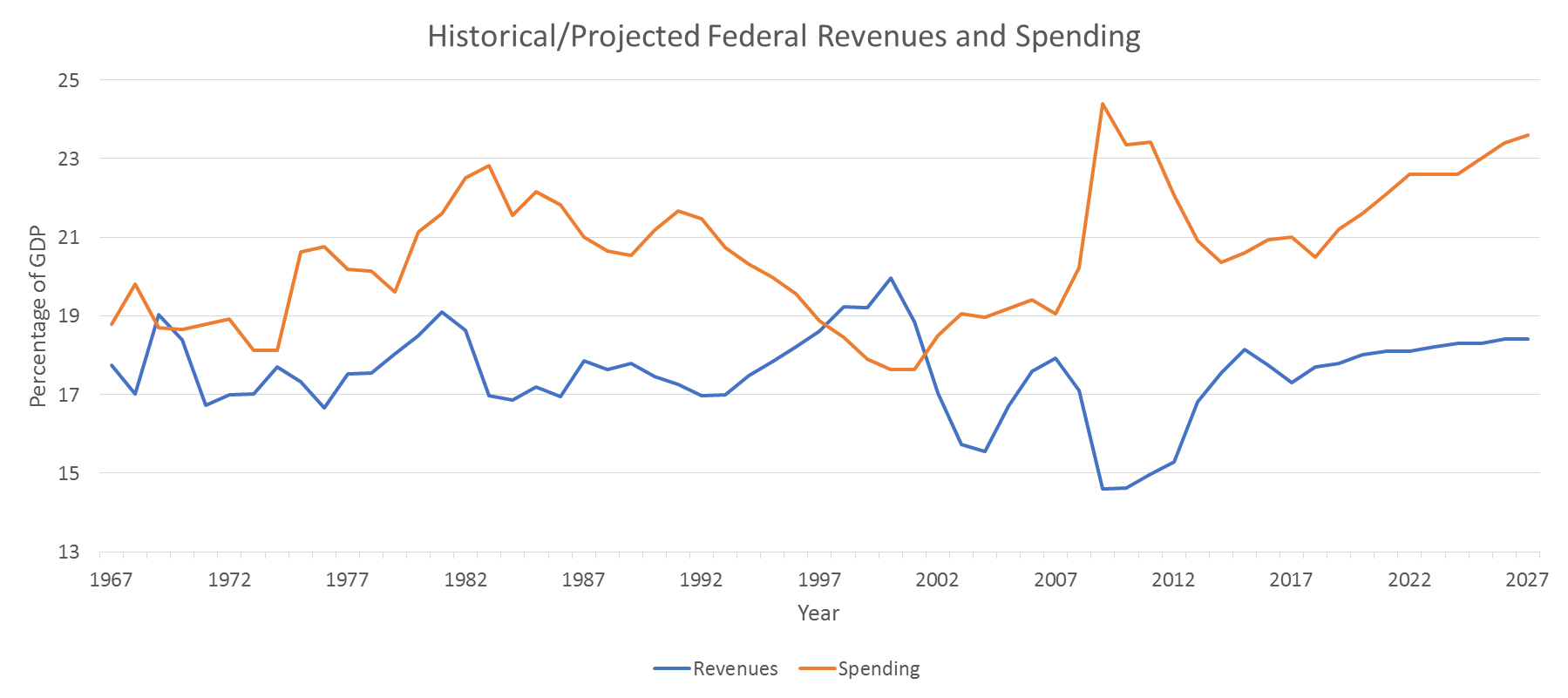

When the tax bill was debated, lawmakers faced baseline budget projections that looked like this:

Everything on this graph is shown as a percentage of GDP, so in effect this shows how both federal spending and (to a lesser extent) revenue collections are growing faster than our economic output. Beyond the time window shown here, the long-term fiscal picture looked even worse. Spending would continue to rise dramatically faster than our ability to finance it, threatening escalating deficits in the decades ahead. The graph also shows that undertaxation is not the cause of this fiscal gap. Over the next decade, tax burdens were actually projected to be higher than the historical average, and to increase gradually faster than our economic capacity.

This was not and is not a stable situation. Taxing and spending as a share of our economy cannot keep increasing forever. (Actually, there is a theoretical sense in which we can spend more than 100% of our economic output if all spending takes the form of domestic income transfers. In other words, we could theoretically tax people several times the amount of their income, providing that we simultaneously write government checks that give it all back to them. However, this is neither practicable nor politically feasible. In the real world we must moderate both our tax and spending growth). Fixing this problem within historical political norms would mean cutting future spending growth substantially – but importantly, also lowering some future tax growth, even as projected deficits are reduced.

In other words, the baseline budget picture was such that there was no contradiction between reducing projected deficits and lowering projected tax collections. Indeed, that is exactly what a solution consistent with historical experience would require.

Now, there is a standpoint from which it would be inconsistent to claim support for both lower taxes and smaller deficits – specifically, if one argued that projected spending growth must never be slowed. Some progressives seek not only to preserve currently projected spending growth but to add enormously to it. In this mindset, deficits could only be closed if tax collections rise faster than projected. Importantly, this would still not produce a stable budget situation because tax collections would need to grow much faster than Americans’ ability to pay them. Nevertheless, some advocates effectively take this policy position.

But those who voted for the tax bill are not generally guilty of this. To the contrary, those members have repeatedly been assailed for their allegedly heartless determination to cut spending. House Speaker Paul Ryan has even been depicted -- in one particularly revolting ad a few years ago -- as dumping an innocent grandmother out of her wheelchair over a cliff, because of his efforts to address rising entitlement spending. And just a few months before their tax vote, lawmakers were attacked for supposedly taking away people’s health care, because of their efforts to tackle hundreds of billions of dollars in projected spending growth under the ACA.

It is legitimate to oppose legislation to slow the growth of federal spending if one believes that spending is needed. But one cannot fairly attack legislators who try to address runaway spending growth, and then later assail those same legislators as hypocrites for widening the deficit.

Now, it is fair to criticize sponsors of deficit-widening legislation for denying they are increasing the debt. There has been a regrettable amount of such denial, where the public would have been better served to hear arguments as to why the benefits of tax cuts outweighed the downside of a debt increase. One can simply assume growth-stimulation effects under which tax cuts do not add to long-term debt, but non-partisan scorekeepers widely reject them -- in the same way they rejected assumptions crafted during the last administration to conclude additional stimulus spending could pay for itself. Advocates should acknowledge adverse fiscal consequences of any legislation under consideration, even as they argue for its passage.

The bottom line is this: prior to the tax legislation, lawmakers faced projections in which both tax burdens and spending patterns exceeded historical norms and were projected to rise still further, driven principally by growth in the major federal health entitlements and Social Security. The merits of this specific tax bill aside, a responsible and sustainable fiscal policy would reduce both projected spending and deficits substantially, while also slowing tax growth somewhat, and ensuring that neither taxes nor spending ultimately grow faster than our ability to finance them. Recognizing these realities involves no hypocrisy, but attacking lawmakers for fiscal recklessness – just a few months after taking political advantage of their efforts to rein in part of the federal spending explosion -- most certainly does.

Charles Blahous, a contributor to E21, holds the J. Fish and Lillian F. Smith Chair at the Mercatus Center and is a visiting fellow at the Hoover Institution. He recently served as a public trustee for Social Security and Medicare.

Interested in real economic insights? Want to stay ahead of the competition? Each weekday morning, E21 delivers a short email that includes E21 exclusive commentaries and the latest market news and updates from Washington. Sign up for the E21 Morning Ebrief.