Reducing the Immigration Backlog High-Skilled Immigrants Face Record-Long Wait Times to Work, Invest, and Innovate in the U.S.

A record backlog of immigration applications has resulted in record-long wait times for highskilled immigrants to come to the U.S. to work, invest, and innovate. The U.S. takes two to 10 times as long to process most employment and skills-based immigration applications as do other rich English-speaking nations. Many high-skilled immigrant applications that take several years in the U.S. are processed within one business day in the United Kingdom. The pandemic slowed the processing of immigration applications but did not cause the current crisis, which was years in the making. In order to alleviate this backlog and make it easier for immigrants— and especially high skilled immigrants—to contribute to the country, this report proposes a series of reforms that should be implemented by United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) and other agencies.

Policy Recommendations

- USCIS should expand premium processing to all immigration benefits, allowing immigrants to pay for faster services. Doing so would provide USCIS with the necessary revenue to end the backlog in four to seven years, while imposing mandatory time limits on the processing of applications.

- Revenue from premium processing should be used to hire new immigration officers to quickly process premium applications first, and then to reduce processing times for regular applications.

- USCIS should call on retired adjudicators to come back to the agency in a part- or full-time capacity, giving them the option to collect retirement and additional pay, while the agency works on hiring and onboarding new staff to reduce backlogs more quickly.

- Reducing the use of work-authorization form I-765 to only the categories of noncitizens that strictly require it would help reduce the workload of USCIS and immediately give work authorization to millions of noncitizens every year, months in advance.

- The State Department should reinstate visa stamping inside the U.S.

- USCIS should make online filing available to all employment-based immigration forms.

- Customs and Border Protection should expand automatic revalidation for H-1B, O-1, and L-1 visa holders and their dependents and expand it to other allied nations.

- Allow immigrants to easily downgrade their EB filing category online with USICS.

Introduction

"Other countries may seek to compete with us; but in one vital area, as a beacon of freedom and opportunity that draws the people of the world, no country on Earth comes close. This, I believe, is one of the most important sources of America’s greatness."—Ronald Reagan, January 19, 1989

As President Reagan remarked, immigrants are one of the most important sources of America’s greatness. Immigrants—especially high-skilled immigrants—drive innovation and entrepreneurship. Immigrants have founded most of America’s billion-dollar companies,[1] despite representing less than 14% of the U.S. population now and much less a few decades ago.[2] Immigrants have also accounted for 28% of all U.S. Nobel Laureates (112 out of 400). The empirical evidence suggests that high-skilled immigrants benefit the labor-market outcomes of less skilled native-born workers while having an ambiguous effect on those of other high-skilled native-born workers, and they benefit the whole population through faster innovation and more investment that raises wages and creates jobs.[3]

“No country on earth” came close to the U.S. in attracting high-skilled immigrants in the Reagan era, but in the 21st century, the country is becoming less desirable for the world’s brightest minds and entrepreneurs. While the number of people who want to permanently leave their countries of birth has risen from 630 million[4] to more than 750 million[5] since 2005, the number of those who would move to the U.S. has declined. Highly skilled foreigners, in particular, are less interested in immigrating to the U.S.: only 9% of interested migrants to the U.S. are college-educated, while 40% didn’t finish high school, compared with 19% who are college graduates and 22% who are high school dropouts for Canada.[6]

The difficulty, as well as the complexity, of the U.S. immigration system has likely contributed to the decline in interest. A constellation of federal policies has made it more difficult for high-skilled immigrants to come to the U.S. and to innovate and start new companies once they are there. The backlog of pending immigration applications has nearly tripled in the last seven years, resulting in longer wait times. Outdated rules delay the employment start date of millions of immigrants.

Americans understand the importance of high-skilled immigration. While immigration as a whole is a controversial political issue, high-skilled immigration is rightfully not. Some 75% of Americans want to encourage and make it easier for high-skilled immigrants to come to the country, including the majority of those who say that they want to “reduce [total] immigration.”[7] Yet widespread support for high-skilled immigration has not translated into similarly supportive policies.

Regardless of what one thinks about the ideal level of immigration, everyone should support a simple and timely process for all legal immigrants, especially those with high levels of education, rare skills, and entrepreneurial potential. There is a strong case for admitting more high-skilled immigrants; but first, we need a simple, efficient, and modern bureaucracy to attract and select immigrants from the largest possible pool of highly skilled individuals. This report identifies why legal immigration processing backlogs have grown and suggests policies that will eliminate them, shorten processing times, and therefore reduce the cost of legal immigration for all—but especially for high-skilled immigrants.ts, forbid entrepreneurship, and increase costs to both the government and immigrants.

Important Definitions and Acronyms

| USCIS | United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS)—a branch of the Department of Homeland Security—oversees lawful immigration to the United States. USCIS determines eligibility for immigration benefits such as visas and naturalization but does not issue visas; visas are issued by the Department of State. |

| CBP | Customs and Border Enforcement (CBP) guards the borders of the United States. CBP staffs legal ports of entry, where it can legally admit immigrants or parole them. |

| Immigrant vs. nonimmigrant visas |

Immigrant visas are those that allow the individual who holds one to enter the U.S. and stay permanently. After an immigrant visa holder settles in the U.S., he receives a permanent residency card, commonly called a “green card,” which the immigrant can then use to travel. Nonimmigrant visas are all other visas—including tourist, student, or work visas—that allow someone to come to the U.S. temporarily. |

| Immigrant intent | Immigrant intent means that the immigrant intends to stay permanently in the United States. All immigrant visas require immigrant intent. |

| Nonimmigrant intent | Nonimmigrant intent means that the visitor intends to eventually leave the U.S. after the terms of his legal stay end. Most nonimmigrant visas require nonimmigrant intent at the time of the grant of the visa. Intent can change after the visa holder is in the U.S., although the process can be complicated. |

| Dual intent | Dual-intent visas can be granted to those who intend to stay and those who intend to return. Nonimmigrant visas such as the H-1B and L-1 are dual-intent. |

| I-90 | Form filed with USCIS by green-card holders to replace lost green cards or to renew if they haven’t naturalized. Immigrants with green cards must renew them every 10 years. |

| I-129F | Form filed with USCIS by a U.S. citizen to sponsor a noncitizen spouse for permanent residency. |

| I-130 | Form filed with USCIS by U.S. citizens and some green-card holders who want to sponsor their relatives to live permanently in the United States. These could be the parents or children of U.S. citizens or the children and spouses of green-card holders. |

| I-140 | Form filed with USCIS by U.S. companies or some immigrants to determine whether they are eligible for employment or skills-based permanent residency. |

| I-485 | Form filed with USCIS by those with an approved I-129F, I-130, or I-140 who are already in the U.S. to receive a green card without going abroad to a U.S. consulate to obtain an immigrant visa. This process is called “adjustment of status.” |

| Consular processing | The process of obtaining an immigrant visa for those outside the United States. For those not already in the U.S., consular processing is the only way to seek permanent residency. Those inside the U.S. can seek permanent residency by filing form I-485. |

| I-539 | Form filed with USCIS by those in the U.S. on a nonimmigrant visa to change to another type of nonimmigrant visa. |

| I-526 | Form filed with USCIS by those who make large investments and create a certain number of jobs in order to apply for permanent residency. |

| I-751 | Form filed with USCIS by immigrants to remove the conditions on permanent residency; often used by immigrants who are the spouses of U.S. citizens after they are married for at least two years. |

| I-765 | Form filed with USCIS by noncitizens seeking a work permit. |

| I-829 | Form filed with USCIS by immigrant investors already in the U.S. with green cards to remove the conditions on their permanent residency and verify that their investment is still viable two years later. |

| I-924 | Form filed with USCIS by regional investment centers seeking designation for the first time so that EB-5 investors can pool their capital in these investment opportunities. |

| I-924A | Form filed with USCIS by regional investment centers seeking annual certification to maintain status. |

| N-400 | Form filed with USCIS by immigrants with permanent residency to obtain citizenship. |

| EB-1 | Immigrant visa for those with extraordinary ability and global recognition. Immigrants or their employers file an I-140 to obtain an EB-1. |

| EB-2 | Immigrant visa for those with exceptional ability and advanced degrees. Employers file an I-140 to sponsor an EB-2 for an immigrant. |

| EB-2 NIW | An EB-2 visa with a National Interest Waiver (NIW), which removes the need for an employer sponsor to file an I-140. |

| EB-3 | Immigrant visa for skilled and non-college-educated workers. Employers file an I-140 to sponsor an EB-3 for an immigrant. |

| EB-4 | Special catch-all category of immigrant visa for various types of immigrants, including allies of the U.S. military abroad and religious workers. |

| EB-5 | Immigrant visa for millionaire investors who create jobs in the United States. |

| Regional investment centers | A more streamlined path to obtain an EB-5, through investment in a government-approved regional investment center, rather than direct investment. |

| TEA | Designated high-unemployment or rural areas where the investment threshold for the EB-5 visa program is reduced to $800,000. |

| B-1/B-2 visas | Nonimmigrant visas granted to short-term visitors to the U.S. for tourism or business purposes. They do not allow holders to work. |

| E-2 visa | Nonimmigrant visa granted to investors (and their families) from countries with treaties with the United States. |

| E-3 visa | Nonimmigrant work visa reserved for Australian citizens who come to work at a specialized occupation. It is similar to the H-1B visa but requires nonimmigrant intent. It was created as part of a free-trade agreement with Australia. |

| F-1 visa | The main nonimmigrant student visa for international college students. It requires nonimmigrant intent. While it is not a work visa, it allows international students to work on campus and elsewhere under certain conditions. |

| CPT | The F-1 visa Curricular Practical Training Program allows F-1 visa holders to work full-time for up to one year, or part-time indefinitely, in order to do internships and other work required as part of their course work. |

| OPT | The F-1 visa Optional Practical Training program allows F-1 visa holders to work one year during their program or after graduation in jobs related to the field of study. It does not require employer sponsorship. |

| STEM OPT | STEM OPT is a two-year extension of the OPT program for F-1 graduates in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math fields. |

| F-2 visa | Nonimmigrant dependent visa for the minor children and spouses of F-1 students. Like the principal visa, it requires nonimmigrant intent. |

| H-1B visa | Nonimmigrant work visa for immigrants in specialized fields that require a college degree or greater experience and employer sponsorship. It is a dual-intent visa. |

| H-1B1 visa | Nonimmigrant work visa similar to the H-1B visa but with reserved spots for Chilean and Singaporean citizens created as part of free-trade agreements with both nations. However, unlike the H-1B visa, it requires nonimmigrant intent. |

| H-2A visa | Nonimmigrant work visa for seasonal agricultural workers in selected fields. It requires nonimmigrant intent. |

| H-2B visa | Nonimmigrant work visa for seasonal non-agricultural workers in selected fields. It requires nonimmigrant intent. |

| H-4 visa | Nonimmigrant dependent visa for the spouses and minor children of H-1B, H-2A, and H-2B visa holders. It is a dual-intent visa for the dependents of H-1B visa holders; and nonimmigrant for dependents of H-2A and H-2B visa holders. |

| J-1 visa | Nonimmigrant exchange visa for researchers, professors, and participants in medical training and cultural programs. It requires nonimmigrant intent and, in some cases, requires the immigrant to spend a number of years in his home country before returning, after the visa expires. |

| J-2 visa | Nonimmigrant dependent visa for the spouses and minor children of J-1 visa holders. |

| L-1 visa | Nonimmigrant work visa for the workers of multinational companies in specialized fields to come to the United States. It is a dual-intent visa. |

| L-2 visa | Nonimmigrant dependent visa for the spouses and minor children of L-1 visa holders. |

| O-1 visa | Nonimmigrant work visa for individuals with extraordinary ability in their fields. It requires nonimmigrant intent. |

| TN visa | Nonimmigrant work visa, created as part of the North American Free Trade zAU*7SZCXAgreement, for citizens of Mexico and Canada in certain professions that require a minimum education or experience. It requires nonimmigrant intent. |

| TD visa | Nonimmigrant dependent visa for the spouses and minor children of TN visa holders. |

| Incident to status | This term is used to refer to benefits or rights that aliens in a specific legal status are entitled to without the need to apply for them, such as work authorization for certain statuses. |

| TPS | Temporary Protected Status is a legal status granted by the president of the United States or the Secretary of Homeland Security to all the citizens of a designated country that is experiencing conditions that make it unsafe for the citizens of that country to return safely—such as a natural disaster, war, disease, or a humanitarian crisis. TPS is available to aliens regardless of whether they enter legally or illegally, or whether they hold another legal status at the time. TPS allows migrants to work for any employer and protects them from deportation. Designations last up to 18 months and must be extended by the executive to continue. |

| DED | Deferred Enforced Departure is a presidentially granted protection from deportation that may also authorize immigrants to work; it is similar to TPS but is not a legal status. |

| Refugee | Under U.S. law, a refugee is someone who is outside the U.S. and “is unable or unwilling to return” to his country of nationality “because of persecution or a well-founded fear of persecution on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion.” The president determines how many refugees to admit and from which parts of the world. |

| Asylum seeker | An asylum seeker is someone who meets the definition of a refugee but is already present in U.S. territory. There is no limit to the number of asylum seekers admitted, since they are already present in U.S. territory. Unlike refugees, they are not immediately authorized to work and must apply for authorization. |

| DACA | Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals is a program created by the Obama administration that protects a number of immigrants who entered the U.S. unlawfully before June 2007 before they turned 16 years old, meet certain educational characteristics, and have not committed serious crimes. They can obtain work authorization. |

| EAD | An Employment Authorization Document is usually a card issued by USCIS that proves that an immigrant has work authorization in the United States. |

| I-94 | An electronic record of arrival and departure issued at legal ports of entry by CBP agents to those legally admitted into the U.S. for a period. |

| PERM | The Program Electronic Review Management is the process and system developed by the Department of Labor to certify that employers seeking to hire immigrants permanently—i.e., sponsor them for a green card—have complied with all laws regarding prioritizing U.S. nationals for the job and paying so-called prevailing wages. |

Growing Backlog and Slower Processing

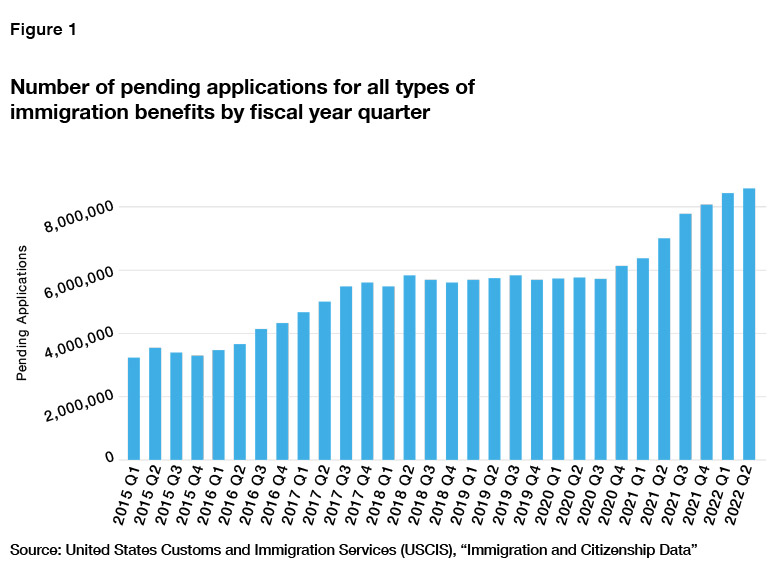

Since 2014, the number of outstanding applications for any type of legal immigration benefit has nearly tripled, from 3.2 to nearly 8.6 million applications in the backlog[8] (Figure 1). Those waiting for their applications to be processed include U.S. citizens sponsoring noncitizen spouses, companies sponsoring high-skilled immigrants, refugees asking for a work permit, and even millionaire immigrants trying to get a green card in exchange for investing and creating jobs in America.

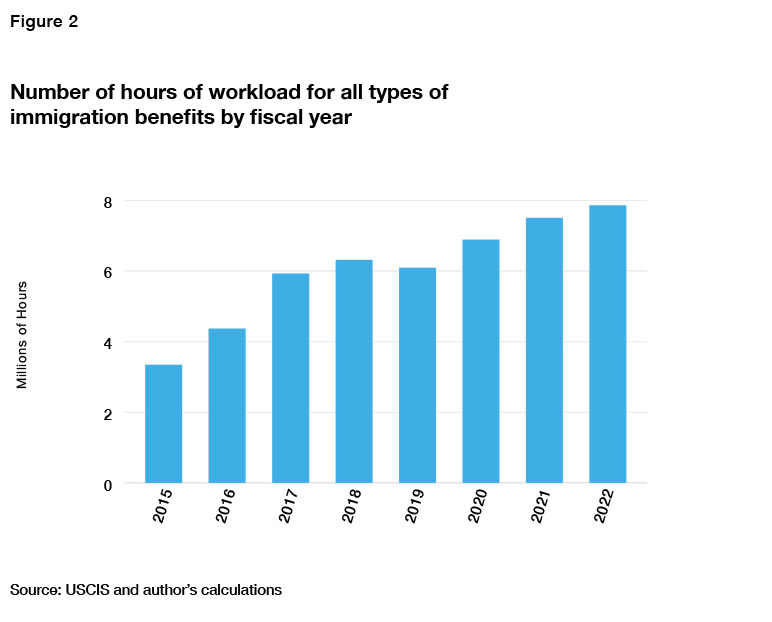

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) is the agency tasked with reviewing and adjudicating all these immigrant applications. Using the most recent available estimates[9] for adjudication time, I found that it would take the agency nearly 8 million hours of work to clear its current backlog—up from less than 4 million hours in fiscal year 2015 (Figure 2).

This means longer wait times for all kinds of legal immigration applications. Between 2014 and 2022, the weighted median processing time for all applications increased by 80%, from two months and three weeks to five months.[10] Processing times vary greatly even for the same form, partly depending on which processing center facility is assigned the case.

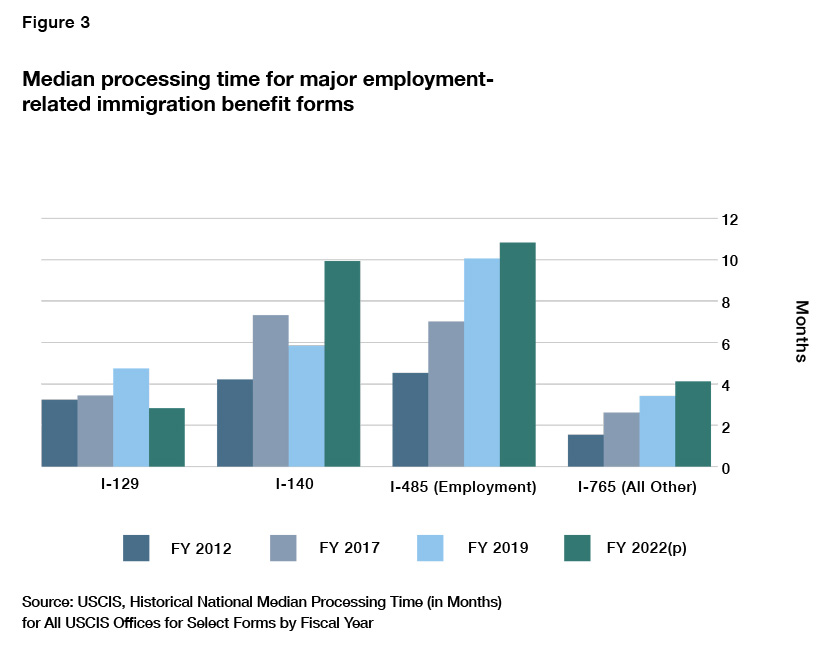

High-skilled immigrants and investors are caught in the backlog as much as anyone else. Ten years ago, a work permit application for an international student or the spouse of a work visa holder, form I-765, would be processed in a month and a couple of weeks; it now takes over four months. The form itself has grown, from one page in 2012 to seven pages today.[11] An application to obtain permanent residency (a green card), form I-485, for a high-skilled immigrant used to take four months and a couple of weeks in 2012; now, it takes nearly 11 months (Figure 3).

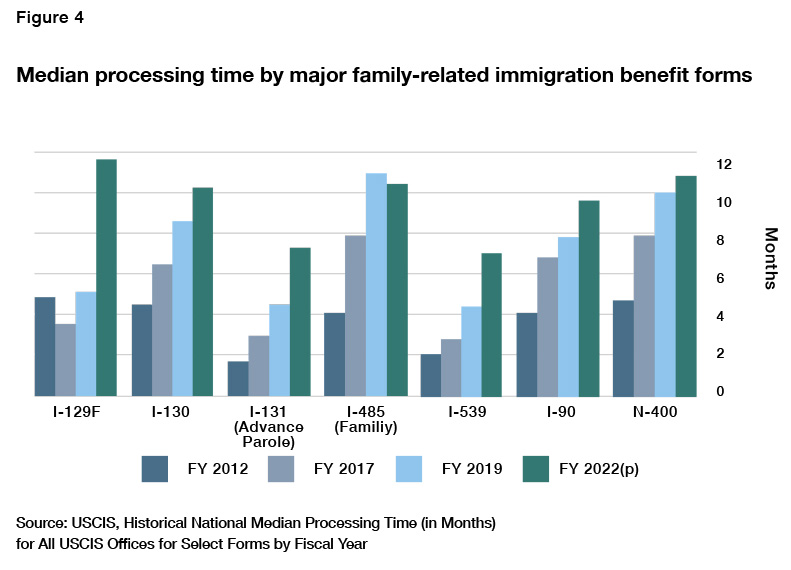

For some family-based immigrants, the situation is even worse (Figure 4). In 2012, form I-130—a request for permanent residency for an immediate relative—was processed in a little more than four months. It now takes over 10 months. But the process does not end there: if the immediate family member being sponsored is already present in the U.S., he must also file form I-485, which used to take four months to process in 2012 but now takes 10 months.

For permanent residents who have already been in the U.S. for several years, it also takes longer to become naturalized. Naturalization applications, form N-400, took five months to process in 2012; they now take 11 months.

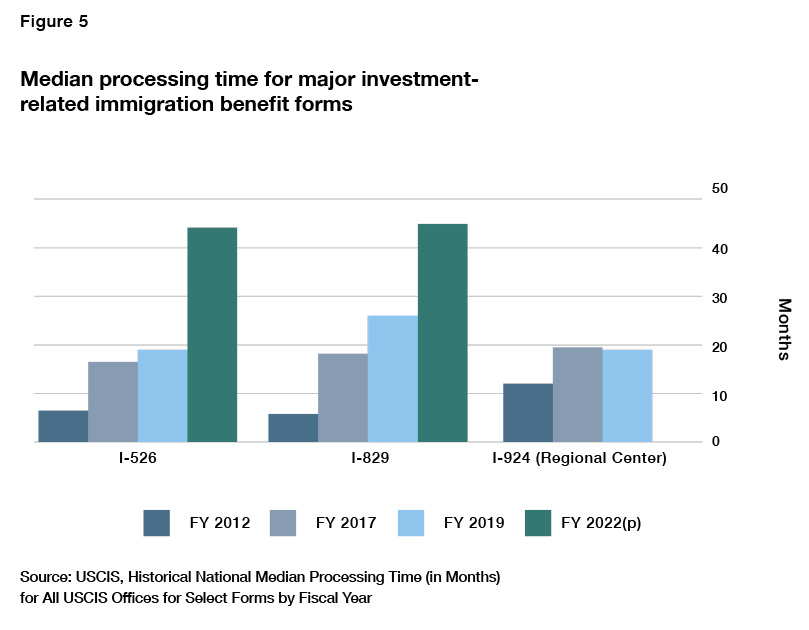

The most affected immigrants are those who wish to invest millions of dollars and create jobs in the U.S., i.e., those who apply for an EB-5 immigrant visa, a form of permanent residency. These immigrants must file form I-526 to verify that their investment is over a certain amount and creates at least 10 direct jobs for U.S. nationals. In 2012, USCIS took seven months to respond to these requests; the agency is now taking 44 months, or over 3.7 years, to do the same. Even after these investors are approved and in the country, they must file another form (I-829) two years later to confirm that they are pursuing the commercial activity that they claimed that they would carry out. Only then do they receive full, unconditional permanent residency. But USCIS now takes another 3.7 years to process form I-829; it used to take less than six months just 10 years ago (Figure 5).

These are the median time frames, which means that half of all applications take longer— sometimes much longer. For instance, the median processing time for adjustment of status (form I-485) is 10.5 months so far in fiscal year 2022, but USCIS also reported that 80% of cases are processed within 15.9 months. In other words, one in five adjustment-of-status applications takes 16 months or longer to process.

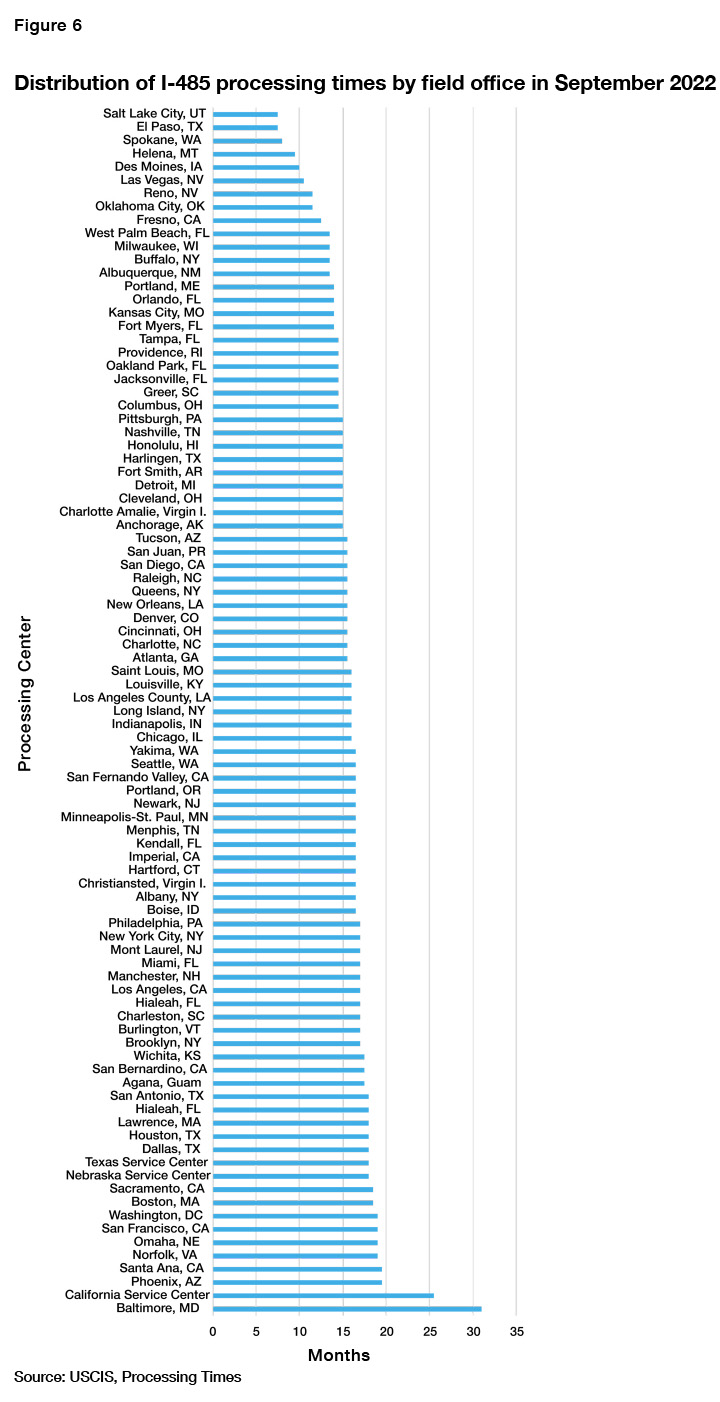

Processing times also vary widely, depending on the center that processed the immigrant application (Figure 6). While 80% of I-485 forms are processed within 7.5 months in Salt Lake City and in the El Paso USCIS field offices, the Baltimore office takes 31 months to process 80% of its applications.

These disparities are also present in other areas. Some 80% of applications for employment authorization (I-765) are processed within 8.5 months in the National Service Center, compared with 17 months in the Nebraska Service Center. An H-1B visa extension request, filed by companies whose H-1B employees want to stay for a second three-year period, takes one month to process in the Texas Service Center and five months in the California Service Center.

Bureaucratic delays in processing two forms—I-485 and I-765—are especially harmful to the largest number of legal migrants. Form I-485 is an application for permanent residency for those who have been sponsored by their employer or who qualify to self-petition. It is also filed by migrants legally present in the U.S. under another status or visa, as an alternative to traveling abroad to seek a consular interview if they are eligible under employment, family, or other greencard category. Form I-765, a work-authorization request, is the most filed immigration form.[12] Most of the applicants are those waiting for a decision on their green-card application (form I-485), international students seeking work authorization after their degrees (F-1 OPT), and asylum seekers.[13] The delays in processing I-765 forms puts many applicants in the uncomfortable positions of not working for many months or risking their legal status by working.

The increased backlog was not caused by the pandemic or by more rigorous security screening— there is simply more demand and less work performed by government employees. Indeed, today’s processing times reflect the continuation of a worrisome and bipartisan pre-pandemic trend. Between fiscal years 2012 and 2017, roughly corresponding to Barack Obama’s second term in office, non-premium (regular) I-140 and I-485 applications wait times shot up by about 50%, a trend that has continued under both the Trump and Biden administrations.

Those seeking to live, work, or study in the U.S. in 2022 are waiting a combined 5.2 million years for responses to 8.3 million immigration forms, an average of seven months and 16 days per form that they filed. If processing times had stayed at 2012 levels, the average processing time would have been less than three months. These delays are unacceptable for the world’s richest and most powerful nation.

USCIS Funding

USCIS is one of the federal government’s few self-funded agencies.[14] Running the legal immigration system costs taxpayers nothing; instead, it is completely financed by the fees paid by immigrants when they apply for a benefit. A typical immigrant will pay thousands of dollars just in fees to the government during the process of becoming a U.S. citizen.[15] Applications for all benefits have risen quickly in the last decade, which has brought more work but also more revenue with which USCIS should have been able to keep up; and the agency has sharply raised fees, even after adjusting for inflation, thus bringing in even more revenue. The agency has hired more employees and processed more applications—but not enough to keep pace with demand.

This self-sufficiency was brought to its limit in 2020 amid the Covid-19 pandemic, when travel bans sharply reduced all types of applications. This led USCIS into a historical budget shortfall that threatened to furlough thousands of employees and shut down legal immigration even further.[16] In response, Congress passed the Emergency Stopgap USCIS Stabilization Act,[17] which gave extraordinary funding to USCIS to keep it functioning and reduce immigration backlogs.

Premium Processing: The Market- Based Solution to Immigration Backlogs

For some forms, USCIS allows applicants to pay for “premium processing,” which legally requires USCIS to respond to applications quickly, between 15 and 45 days, depending on the type of application.[18] Currently, these are the only applications that the agency processes in a timely manner, and many important forms, such as I-485 and I-765 (discussed above), are not eligible for premium processing. The service is expensive; it can cost another $2,500 on top of the regular fee for form I-140.

The 2020 Emergency Stopgap USCIS Stabilization Act required USCIS to expand the number of forms eligible for premium processing,[19] and it increased fees for those that were already eligible. This law also authorized the president to expand premium processing to all other immigration forms not specifically mentioned in the bill. But USCIS has been slow to implement the law; it has taken a phased approach[20] and is just now expanding premium processing to two greencard categories in form I-140 that were not previously eligible.

To fix the immigration backlog and shorten processing times, the president or the secretary of Homeland Security should drastically expand premium processing to all main immigration benefits. Expanding premium processing would increase USCIS funding and staffing exclusively dedicated to reviewing immigrant petitions. Most important, it would legally bind the agency to adjudicate petitions in a timely fashion.

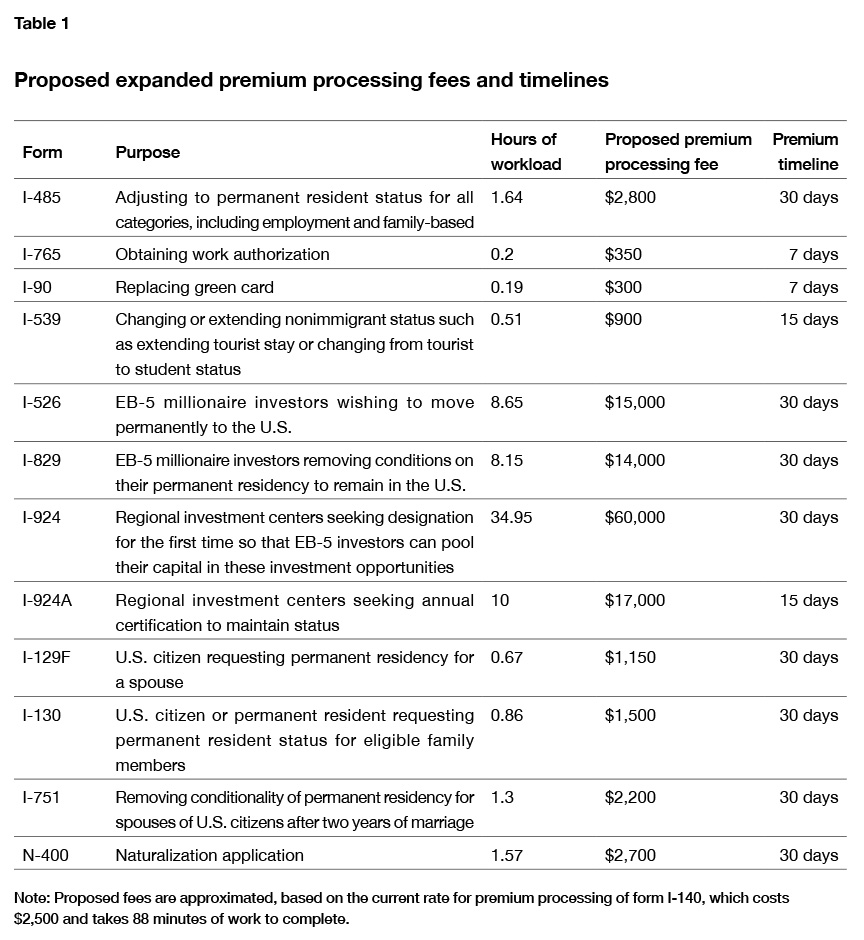

The implementation and pricing of expanded premium processing should be based on how much work a given form requires the agency to do. Consider form I-485, which is not currently eligible for this service. The agency reports that it takes an average of 98 minutes[21] to adjudicate each employment-based I-485 form, and the median processing time is currently 10 months.[22] With premium processing, the agency could be required to respond in just 45 days. Given that the agency charges $2,500 for 45-day premium processing of form I-140[23]—which takes an average of 88 minutes to adjudicate[24]—a reasonable fee for I-485 should be proportionally greater, at $2,800. At that additional price, many employment-based migrants would probably pay to save 10 months.

To avoid a sudden inflow of applications before USCIS has enough time to hire more immigration agents, the agency should phase in the premium processing expansion, as it is already doing for certain I-140 categories. The agency should start with petitions that have been waiting for over a year and then advance in a predictable schedule. For instance, forms filed before January 1, 2022, would be eligible to upgrade to premium processing in January 2023; those filed before March 1, 2022, would be eligible in February 2023; and so on, until newly filed forms are eligible in January 2024.

USCIS should simultaneously expand premium processing across the board, including for investment-related immigration petitions, family-based immigration, naturalization, and other requests. The proposed expansion is detailed in Table 1. Expanding premium processing to immigration categories not related to high-skilled migration would benefit high-skilled immigrants. First and most important, the revenue from expanding premium processing to unrelated categories would allow USCIS to hire more employees to process all types of petitions, including those of high-skilled immigrants and their families. Second, reducing processing times for other immigration benefits could entice more high-skilled migrants to come to the United States. Many high-skilled immigrants marry other immigrants after obtaining their permanent residence, they hope to naturalize and become U.S. citizens, and they hope to bring their parents to live with them.

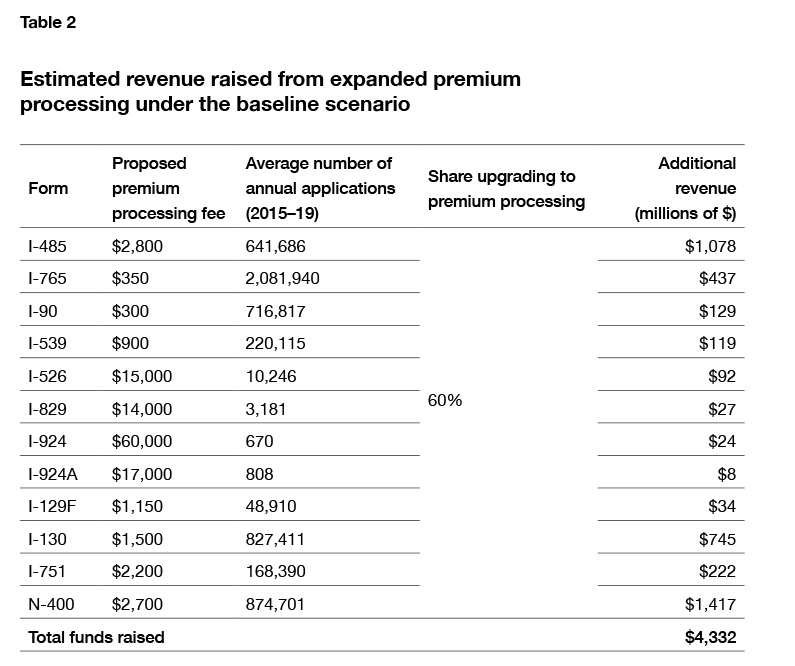

This expansion of premium processing for these categories will greatly increase revenue for USCIS, which it should be required to use to hire staff and modernize its system. While it is uncertain how many would apply in the initial phase as the service is gradually phased in, we can use the data on how many take advantage of the service where it is currently offered to make assumptions about how many will choose premium processing once the phase-in is complete. We can combine that figure with an estimate of a reasonable price for each form, as we did for form I-485, in order to arrive at the total revenue that USCIS could expect from expanding premium processing.

Expanding premium processing to the main immigration forms listed in Table 2 could raise an additional $4.33 billion annually for USCIS. For comparison, the fiscal year 2021 budget for USCIS totaled $4.75 billion,[25] which means that this reform could almost double the USCIS budget. The premium usage rate would depend on the form, but 60% is a conservative estimate. The rate for form I-485 would likely be much higher, since obtaining permanent residency is critical for employment and legal security in the U.S., and the regular processing time today is nearly one year. Other forms, such as naturalization applications (N-400), may see lower usage because immigrants can afford to wait for the benefits.

Even using a generous estimate of nearly $240,000[26] in employment costs for each additional USCIS agent—which represents its entire budget divided by its 20,000-strong full-time equivalent workforce[27]—the added revenue would fund 18,235 new USCIS employees dedicated to processing these premium applications and all the infrastructure maintenance and services that they require. If just half these new employees are responsible for processing immigrant petitions and they work the nationwide-average 34.5 hours per week,[28] USCIS will have a total of 16.4 million more hours of adjudication annually.[29]

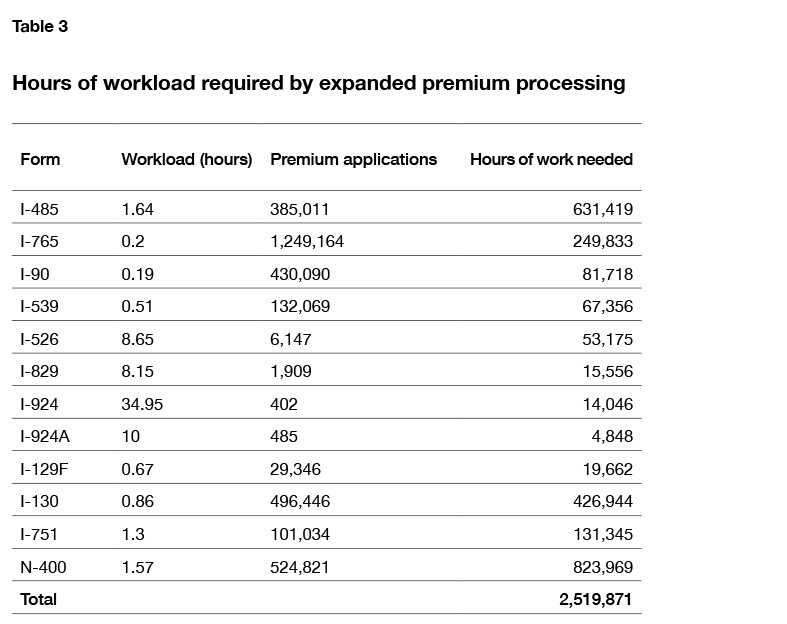

Expanding premium processing reduces inefficiencies by allowing those who need a quicker decision to pay for it. But it also benefits those who do not pay for the service. Of the 16.4 million adjudication hours available because of the proposed premium processing expansion, premium requests will require an immediate 2.5 million hours (Table 3), leaving approximately 13.9 million hours available to adjudicate non-premium petitions. Even under an extremely pessimistic scenario, where only 30% of applicants choose premium instead of 60%, the new revenue would still cover approximately 9,118 new USCIS employees, half of whom could be dedicated to adjudication alone, leaving still some 6.9 million hours of adjudication work available after processing all the premium applications.

For comparison, the current total backlog of all immigration benefit petitions will take about 8.1 million hours to complete.[30] We do not have workload estimates for all forms, but the ones that we lack data for are not major parts of the backlog. The additional revenue from expanding premium processing would allow USCIS to hire enough adjudicators to clear all the immigration backlog in one to two years without any changes to immigration law or procedures.

The hiring process, security screenings, and onboarding for a new immigration officer can take several months. Even after a new officer is vetted and hired, the required onboarding course reportedly takes some 200 hours to complete.[31] However, USCIS has previously been able to hire quickly by allowing retired immigration officers to return at their last salary rate, while they also collect their federal employee retirement benefits.[32] Returning USCIS employees could get to work immediately, since they have been through background checks and have decades of experience. USCIS could also offer more generous overtime pay for current immigration officers to do premium processing in the first year of expansion in order to quickly reduce the backlog as new, more permanent, jobs are filled.

There is no public information on how many retired USCIS employees there are, but we know that the agency’s 19,000 employees accounted for 0.68% of the federal civilian workforce in 2021.[33] In 2018, there were nearly 2.7 million retired federal employees[34]—so, assuming that immigration officers account for the same 0.68% share of retired federal workers, it is reasonable to estimate that there are 18,000 former USCIS employees. Even if only 5% of them were willing and able to come back to work temporarily as the agency hires new permanent employees, that would mean nearly 1,000 new USCIS employees, meaning that it is reasonable to assume that hiring could start immediately after premium processing begins to be phased in.

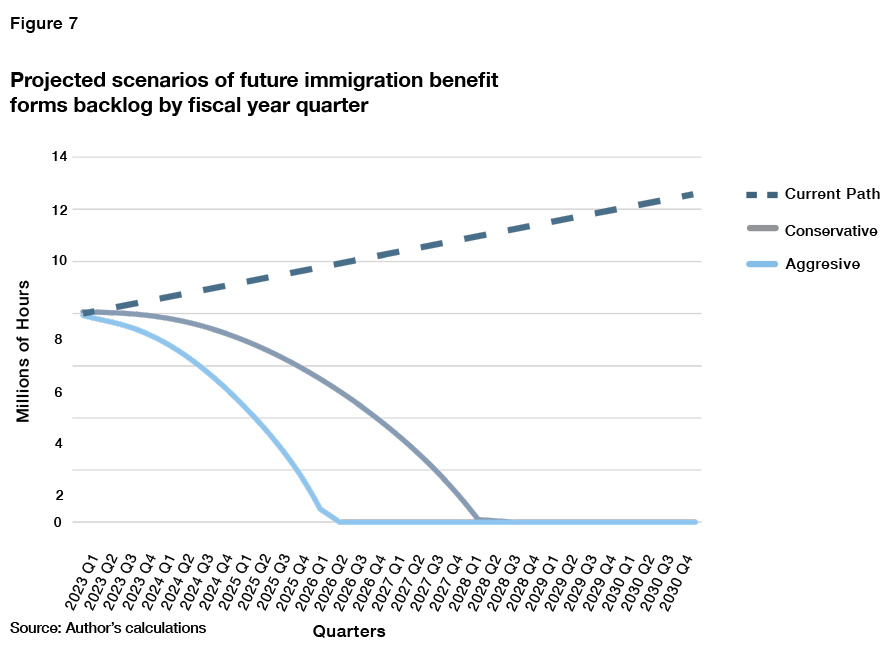

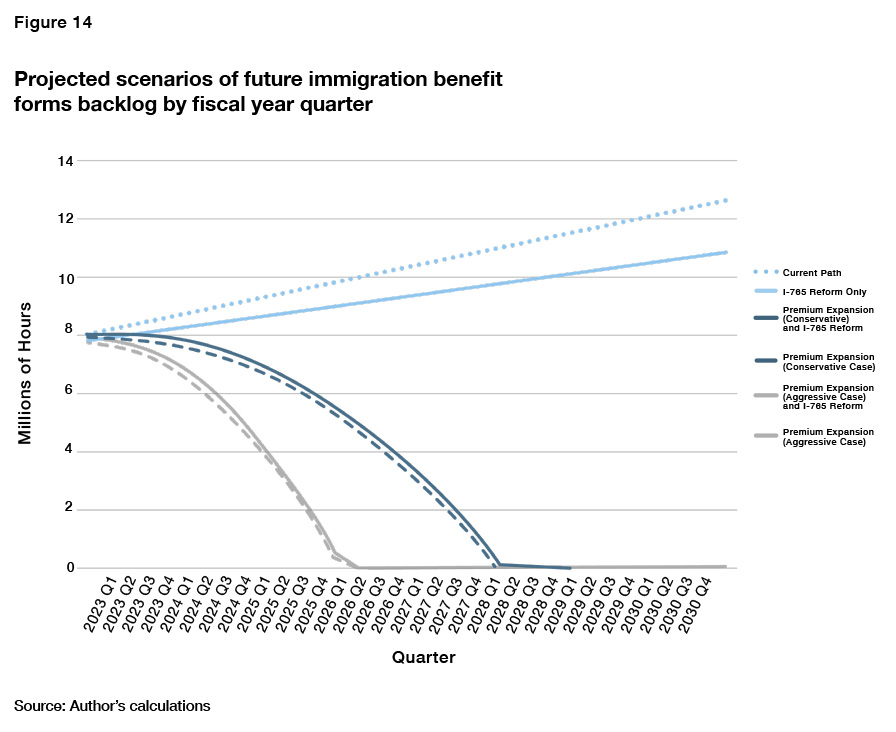

We can model how long it would take to clear the backlog if the expansion of premium processing had been implemented starting in fiscal year 2023, which started on October 1, 2022. In Figure 7, I present the current projected backlog, as well as two scenarios for the number of new hires USCIS could add with the revenues from expanded premium processing, taking into account the agency’s current size (20,003 full-time-equivalent employees) and the national average annual hiring rate of 4.21% through October 2022.[35] In the conservative scenario, premium processing would allow the agency to add 842 more employees than it is currently projected to add each fiscal year. In the aggressive scenario, I assume that the agency will be able to hire 1,824 more employees than projected each fiscal year. These assumptions are realistic—and even conservative—given that between fiscal years 2015 and 2021, USCIS increased its annual hiring rate by 6.8%.

Although shortening processing times for all these immigration benefits may raise demand for them—meaning that the backlog could not be reduced as quickly—it is important to note that more demand, especially for premium processing, also means more fee revenue for the agency to hire more employees. Greater demand, therefore, could even help reduce the backlog at a faster pace than projected because of the spillovers from the premium processing revenue to process other applications.

Assuming that the increasing trend of immigration applications since 2015 continues, the backlog of immigration benefit forms is projected to reach 12 million workload hours by the end of the 2029 fiscal year, up 50% from the 8 million workload hours of backlog today.

Under both scenarios described in this report, the immigration processing backlog would be completely erased within the next five years. Under the conservative scenario of hiring speed, backlogs are erased by the first quarter of fiscal year 2028, taking a total of five years. Under the aggressive scenario, the backlog is erased even earlier by the first quarter of fiscal year 2026, just three years from implementation.

Ending Form I-765 as We Know It

Another cause of long immigration processing delays is the sheer number of forms required, many of which are unnecessary. USCIS should start phasing out many required forms and combining others in order to reduce processing times for immigrants and dedicate more time to important immigration petitions.

The most filed and overused form is the I-765 work-authorization request. Many categories of noncitizens are almost automatically approved for a work permit upon filing this form, unless there is a clerical error, such as a misspelled name or a missed checkbox. Individuals in those categories should not be required to file form I-756 and should instead receive automatic work authorization through other means so that USCIS can focus its resources elsewhere.

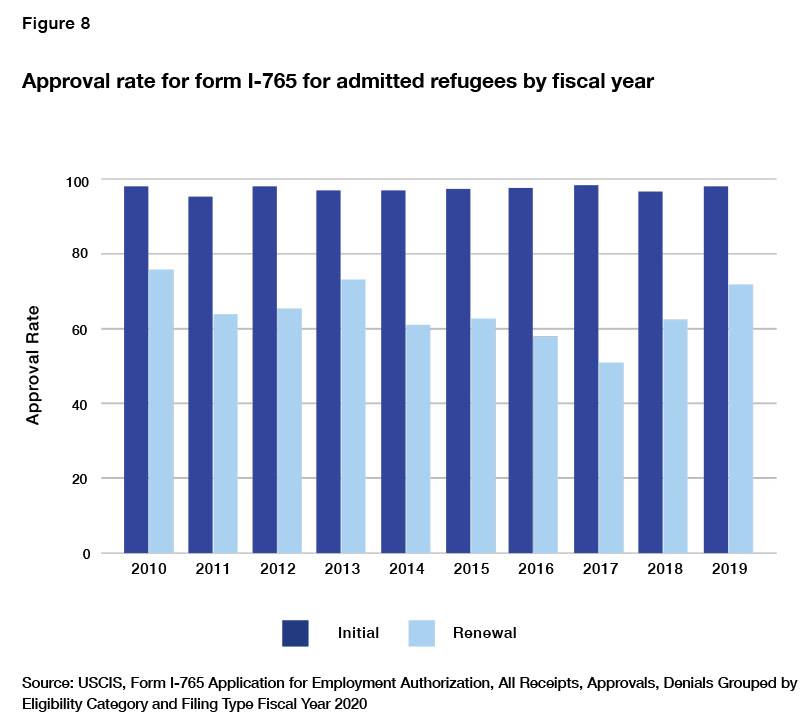

Recently arrived refugees, vetted abroad and admitted through the State Department, can work legally right away with only their passport stamp. Nevertheless, USCIS files form I-765 for them after they get to the United States. Over 97% of these I-765 applications are approved—and thus a one-year work permit is issued—while only about 66% of renewal applications are approved (Figure 8).[36] To reduce backlogs, USCIS should not file form I-765 for refugees and should instead allow them to work using their visa stamp for at least 18 months, since refugees are eligible for green cards one year after arriving. An 18-month period would give refugees time to file for permanent residency, while freeing up USCIS resources.

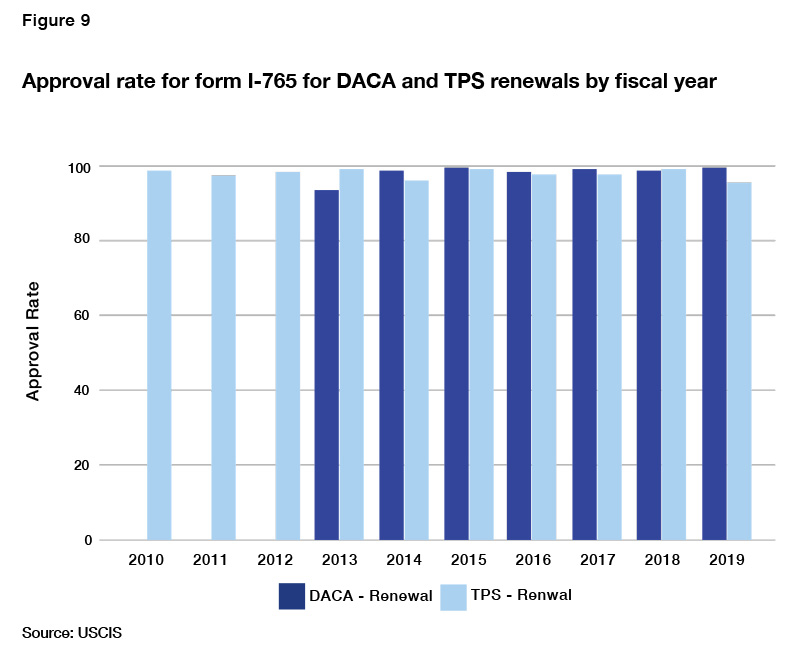

The same is true for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) recipients, who must renew both their DACA status and work permits every two years. Instead, USCIS should merely ask them to renew their status and automatically extend their work permit without requiring them to file form I-765 again. The approval rate of DACA work-permit renewals is over 99%, and they represent 25% of all work-permit requests every two years.[37] Another similar category is Temporary Protected Status (TPS). TPS recipients—who now outnumber DACA recipients— have to file form I-765 even more frequently, every 18 months. These renewals are also almost always approved (95%) and represent 8%–19% of all I-765 forms filed annually (Figure 9). USCIS should automatically extend the work permits of TPS recipients every time a TPS designation is extended by the president or the secretary of Homeland Security.

These simplifications of immigration procedures may seem unrelated to high-skilled immigration, but they are very much related. USCIS employees should not be spending tens of thousands of hours each year, the equivalent of many hundreds of additional USCIS employees, to process unnecessary paperwork when they could be adjudicating a more time-consuming immigrant investor petition to create hundreds of jobs in the U.S. or the petition of a CEO of a multinational opening a new office. Since resources are finite, simplifying one part of the immigration system leads to positive spillovers for the rest.

Two other groups that should be exempted from filing form I-765 are those adjusting status to permanent resident and the spouses of H-1B workers with an approved I-140. The first group represents the largest share of immigrants filing form I-765—some 47% of all applications in 2019—and the category that most directly affects high-skilled immigrants.

Depending on the category that they fall into, immigrants who have filed form I-485 to adjust status may have to file form I-765 to work at all, or to change jobs if they are already on a work visa. Since 2011, immigrants who have applied for permanent residency can also file form I-765 alongside a request for “advance parole,” which allows immigrants to leave and reenter the country while their application is pending. Since 2015, the H-4 spouses of H-1B workers who have received an approved form I-140—the step before adjusting to permanent resident—can also file for employment authorization using form I-765 without filing form I-485. This was meant to benefit mainly Indian immigrants facing a decades-long green-card backlog caused by per-country caps who could not file form I-485 until a green card became available to them.

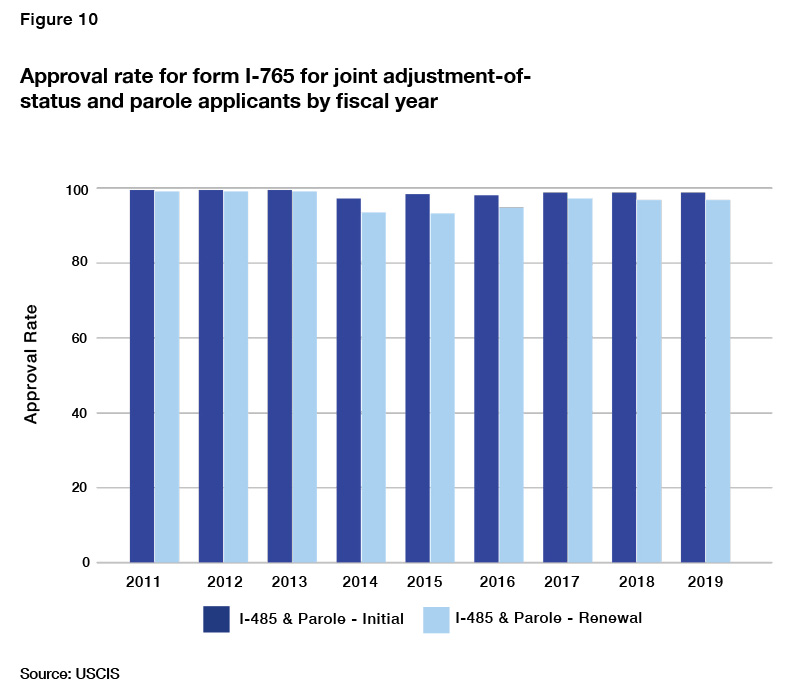

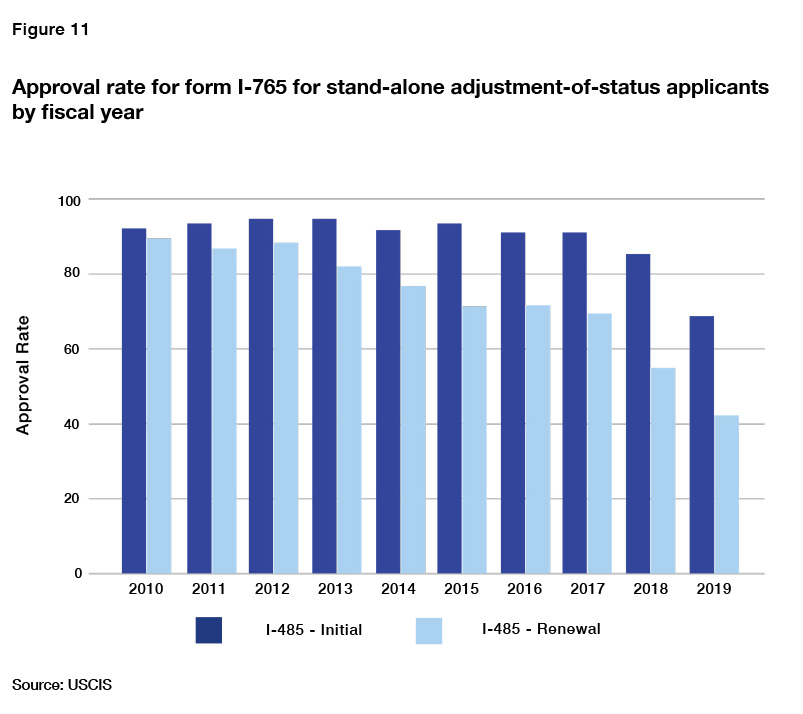

As shown in Figures 10 and 11, the I-765 approval rate for these groups combined is very high— approximately 90% over the last 10 years. For some in this group, the approval rate has trended downward in recent years—most likely, because their application for permanent residency was approved first. USCIS took 8.5 to 17 months to process 80% of I-765 forms filed by immigrants with pending adjustment of status applications. Since the median processing time for form I-485 is 11 months, many immigrants likely obtained their green cards while they waited for the permit that was supposed to let them work while they waited for the green card.

The requirement to file form I-765 for immigrants adjusting status has become futile. The U.S. government is forcing immigrants who are already in the country and will most likely obtain their green cards to wait for them either without working or without switching employers, should an opportunity arise. This creates uncertainty, makes life more difficult for high-skilled immigrants, and slows down our economy.

H-4 spouses of H-1B visa holders with approved I-140 petitions should also be exempt. Many of these individuals currently have to wait over a year before working while their I-765 petition is approved. But these migrants are, in all likelihood, highly skilled themselves. One estimate by the American Action Forum suggests that nearly 90% of the H-4 visa spouses of H-1B visa holders have a college degree and nearly half, a graduate degree.[38] Those who have an approved I-140 petition are likely to be even more highly educated and have greater earnings potential.

Instead of forcing immigrants to wait a year before working while the government processes forms that are almost guaranteed to be eventually approved, USCIS should allow immigrants to work and travel abroad by showing a receipt notice for form I-485 and an approval notice for form I-140 or I-130, not requiring the filing of form I-765 or an advance parole application. Additionally, USCIS should allow H-4 spouses of H-1B workers with an approved I-140 petition to prove work authorization, using the certificate of their marriage to the H-1B holder, their visa stamp, and the form I-140 approval notice. This would not change eligibility for work authorization, and it would save USCIS hundreds of thousands of hours of work annually, which could be spent reducing the backlog of permanent residency applications that is causing this problem in the first place.

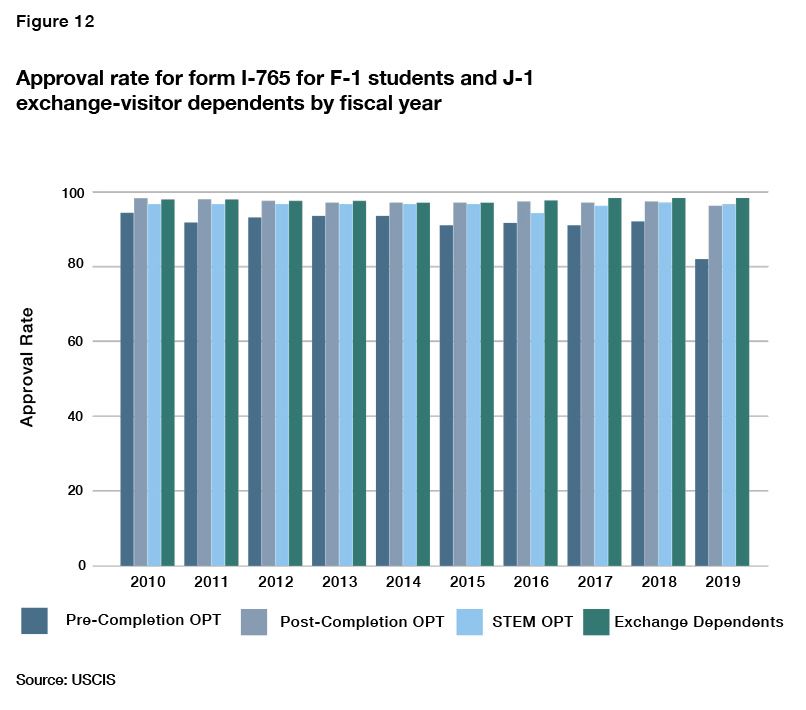

International students also should not have to file form I-765 applications in order to obtain work authorization. Through the Optional Practical Training (OPT) and STEM OPT programs, F-1 student visa holders—after filing form I-756—are allowed to work for one year after graduation, and those with STEM degrees have the option to renew for another two years. Both programs have approval rates of over 97% (Figure 12), since students must first obtain permission from the school, through Immigration and Customs Enforcement designated school officials, and then file form I-765. This duplicative process disrupts the work plans of international students who do not know when their work permit will arrive and therefore do not know when to tell prospective employers they can start. It leads many of them to lose job opportunities and makes the U.S. a less desirable destination for international students, many of whom bring tens of thousands of dollars annually into our economy.

This system does not make sense because international students do not have to file form I-765 for another form of work authorization that they can receive: Curricular Practical Training (CPT). Unlike OPT, CPT authorizes work as part of a course of study while the student is enrolled or on break. Many international students use CPT for full-time or part-time internships. OPT could work the same way: international students could get authorization to work from a DSO and use their I-20 form, issued by the school, as proof of work authorization, just as CPT recipients do for internships. This reform would reduce filings for form I-765 by over 10% annually and save $410 for each student in filing fees.[39]

Exchange dependents are in a related category to international students. They are under a dependent J-2 visa, which is for spouses and children of J-1 visa holders, who are generally professors, scientific researchers, and physicians who work in the U.S. for a short period. (Au pairs and cultural exchanges also come to America on J-1 visas but are not allowed to bring dependents on J-2 visas.) The J-2 visa is therefore only for the spouses and minor children of these researchers, who are generally high-skilled immigrants but cannot work without filing form I-765.

This is unnecessary, given that the dependents of other high-skilled immigrants—like intracompany transfers on L-1 visas and investors from countries with treaties with the U.S. on E-2 visas—are allowed to work as soon as they arrive, using their entry form provided by Customs and Border Enforcement, form I-94. These rules should be extended to J-2 visa holders, allowing them to work as soon as they arrive in the U.S.

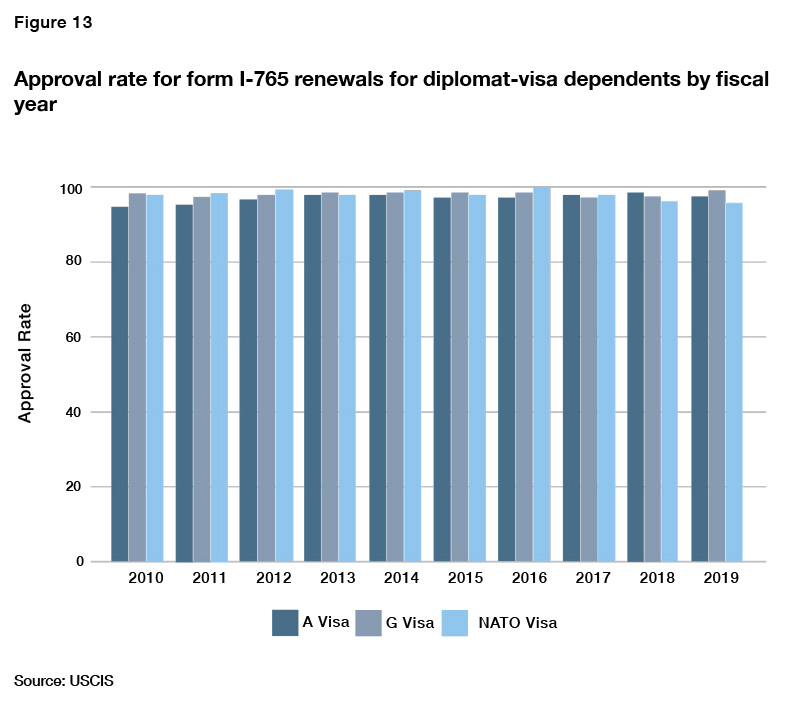

Finally, a small category of immigrants who file form I-765 but can be exempted from doing so are the family members of foreign diplomats and employees of international organizations. Some dependents of foreign ambassadors and other embassy staff, employees of institutions such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, and those in the U.S. on NATO military deployments are allowed to work in the United States. They come under various types of visas, including A, G, and NATO visas. The I-756 approval rate is over 95% in all these categories (Figure 13). Rather than having to undergo a burdensome, months-long process to obtain work authorization, dependents of A, G, and NATO visas should be allowed to work in the U.S. upon arrival, in the same way proposed above for J-2 visa holders.

These reforms would discontinue the use of form I-765 for 96% of all the filings in the 2010– 19 period. It would focus the attention of USCIS on applicants with the highest denial rates and on those for whom a work-authorization document is especially important, such as initial TPS and DACA recipients, who have no legal status and thus need a document that proves work authorization.

These proposals would reduce the number of I-765 forms filed annually by more than 2.1 million, which eliminates more than 400,000 hours of adjudication work. Because USCIS agents can repurpose this time to process other applications, reducing bureaucracy is twice as effective at reducing the backlog as hiring more USCIS employees.

By themselves, the I-765 reforms would only slow the growth of the backlog but would not stabilize it or reduce it. The reforms would reduce the backlog at the end of the 2029 fiscal year by more than 13%, compared with the current path, saving nearly 1.6 million hours of work while making it easier for immigrants to work (Figure 14). If I-765 reform is combined with expanded premium processing, however, USCIS could erase the backlog several months sooner than in either the conservative or aggressive hiring cases.

Other Commonsense Solutions

Digitizing the Immigration System

The most commonsense improvement to legal immigration processing is digitization. In the 21st century, immigration applications should be online by default; and mail should be the exception, not the rule. Unfortunately, even in fiscal year 2021, less than 20%[40] of all immigration forms were filed online, and most forms are still not eligible for online filing.[41] Many procedures, such as receipt and approval notices and requests for evidence, are still sent by mail to applicants, wasting valuable government funds and time for USCIS employees as well as immigrant waiting for decisions. USCIS should implement a system that allows immigrants to, at the bare minimum, receive receipt notices, approval notices, and requests for evidence on their cases exclusively through their online accounts with USCIS, which they can already use to follow the progress of their case.

Furthermore, USCIS should implement a plan to fully digitize immigration applications for high-skilled related categories such as employment-based adjustment of status form I-485 and immigrant and nonimmigrant worker petitions forms I-140 and I-129.

Visa Stamping Inside the United States

In the past, immigrants traveling outside the U.S. could send their passports to designated offices to stamp them before they left the country. But many of these consulates are understaffed and inefficient—and some still remain closed[42] or claim delays, allegedly due to the pandemic.[43] This tragedy is especially affecting H-1B visa holders from India, where wait times for visa appointments at U.S. consulates can be longer than a year.[44] This process separates high-skilled immigrants living in the U.S. from their families and causes unnecessary hardship. Additionally, immigrants traveling to a consulate abroad to restamp their passports risk getting stuck outside the U.S. on procedural grounds with no legal standing to sue, since these decisions are final and they are physically outside U.S. jurisdiction. The State Department should heed the recent unanimous recommendation by the Presidential Commission on Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders to resume stamping inside the United States.[45]

Expand Automatic Visa Revalidation

Another solution to reduce the burden on U.S. consulates and reduce waiting times to travel and see family is to expand automatic visa revalidation to certain high-skilled immigrant categories all over the world. Automatic revalidation is a process that allows international students and researchers on F-1 and J-1 visas to visit Canada, Mexico, and some adjacent Caribbean Islands for 30 days or less and return to the U.S. even if their visa stamp is expired.[46] The program is available to H-1B, O-1, and L-1 visa holders and their dependents, only if they visit Canada and Mexico for less than 30 days but not any adjacent Caribbean Island. Automatic revalidation should also be available for travel to other allied countries that fully cooperate with security and immigration authorities, in order to ease the need to visit consulates by these high-skilled immigrants, who are seldom lawbreakers. If expanded to India and the European Union, NATO members, and nations with whom the U.S. has special immigration treatment, such as Chile and Australia, automatic visa revalidation expansion could single-handedly solve the consular appointment shortage problem and make high-skilled immigration much quicker.

Online Change of EB Category

Many immigrants from backlogged countries like India and China who are seeking permanent residency through the second preference employment category, EB-2, will voluntarily downgrade to the third preference employment category, EB-3, if the latter category has an earlier priority date.[47] To do this, they must file an entirely new I-140 form. This is unnecessary because, by definition, all those who qualify for an EB-2 immigrant visa also qualify for an EB-3 visa. To reduce the number of I-140 forms filed, USCIS should allow these immigrants and their employers to change their filing category online through their accounts with USCIS without requiring them to file another form that will invalidate the former.

America vs. the Rest of the World

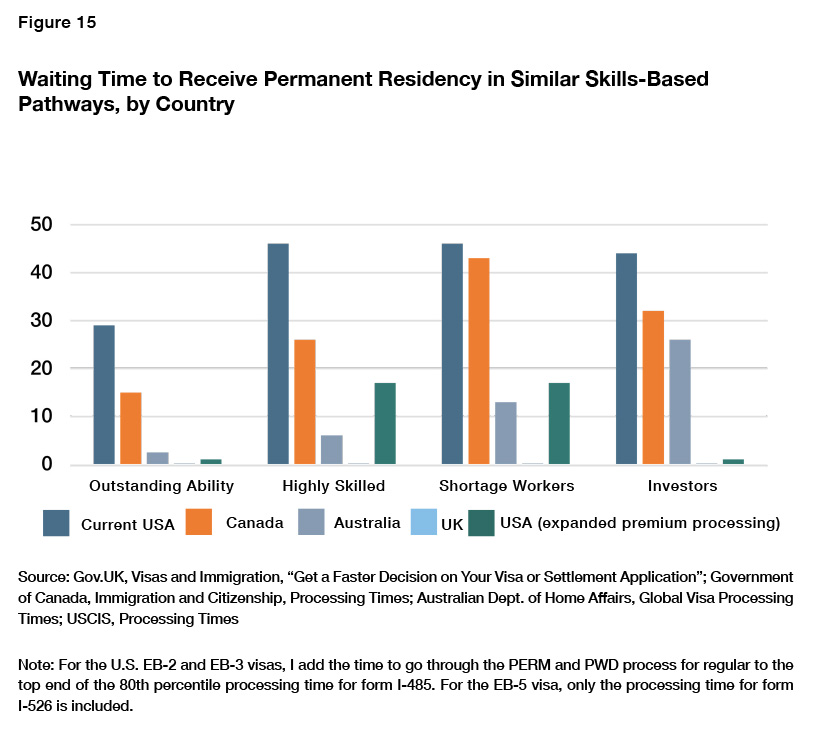

An important reason that American political leaders should take the rising immigration backlog seriously is that peer nations have developed much faster methods to allow high-skilled legal immigrants into their countries, which likely explains why high-skilled migrants worldwide are less likely to want to move to the U.S. today than they were a decade ago.

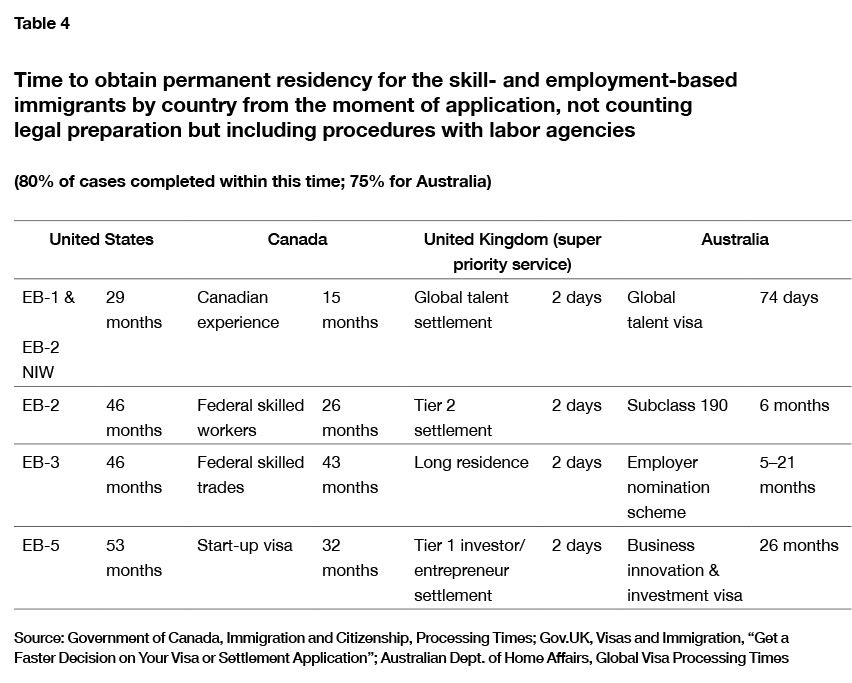

If we do not start attracting more of the best and brightest now, there will soon come a time when we will not be selecting high-skilled migrants but instead, begging them to come. The easiest way to attract the best migrants to our applicant pool is to make the process as quick and as streamlined as possible, without sacrificing security vetting, of course. Table 4 shows how the U.S. is doing, compared with other nations.

The categories used by other countries are not exactly equivalent, but they are similar enough to give an idea of how far the U.S. is behind other developed English-speaking nations. As shown in Figure 15, Canada is the closest, but it is still faster than the U.S. for all categories. A worldrenowned scientist with a Nobel prize would qualify for both EB-1 permanent residency in the U.S. and for Express Entry through Canada’s various pathways. If this individual had previously been working in Canada under a work visa, he could obtain permanent residency in Canada within 15 months, half the 29-month wait in the United States. In Australia, the difference is even greater; the Nobel prizewinner would be able to receive a decision on a Global Talent Visa within 74 days, 90% faster than in the United States. But Nobel prizewinners are not the only type of immigrant who qualifies for this type of permanent residency: all people with world-renowned skills in their field, such as athletes, CEOs of major companies, important professors and doctors, and even some entrepreneurs and people with high levels of education and earnings use this path.

The more commonly used high-skilled immigration pathways usually require a graduate degree and employer sponsorship, except in Canada, where most migrants can apply on their own, and Australia, where a person must be nominated by a state. In the U.S., this process (EB-2) takes 46 months, including all procedures but not preparation time. Canada’s express entry as a federal skilled worker is shorter, at 26 months. In Australia, a subclass 190 visa takes only six months to process from application.

But the great outlier and most efficient nation when it comes to legal immigration, especially high-skilled immigration, is without a doubt the United Kingdom. The U.K. usually processes most immigration applications within a year but allows immigrants to pay for “super priority” or “priority” services to receive decisions in one or five business days, respectively. This speed is not only unmatched but is also relatively cheap; priority service costs £500, and super priority costs £800.[48] The U.K. processes high-skilled immigrant applications faster and at a lower cost than the U.S., which charges a premium processing fee for I-140 forms of $2,500 and still makes immigrants wait upward of three years for the whole process.

If the U.S. expanded premium processing for form I-485 as outlined in this report, EB-1 processing times would drop from the current 29 months that it takes to process 80% of I-485s filed concurrently with an I-140, to just 30 days. This would put us ahead of Canada and Australia but still behind the U.K.’s one-business-day processing time. One month is a much more reasonable time frame to expect a highly skilled person to wait for American permanent residency. This same expansion of premium processing would also speed up EB-2 and EB-3 decisions—though not by as much, since they still must go through the Labor Department’s prevailing wage and PERM processes. Still, expanding premium processing to form I-485 would more than halve the timeline to obtain these two forms of permanent residency and put us ahead of Canada but still behind Australia. For immigrants looking to invest at least $1 million, expanding premium processing for form I-526 would shorten processing times from over four years to 30 days or less, putting us far ahead of Canada and Australia, whose investor immigration programs are also severely backlogged.

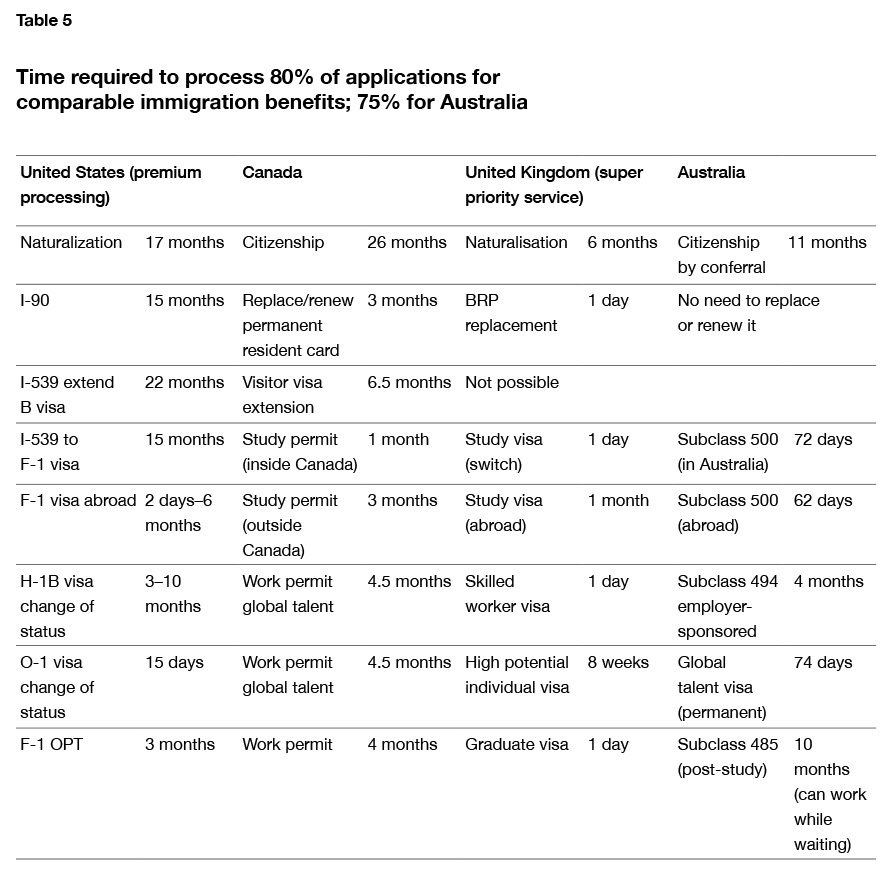

Australia, Canada, and the U.K. have shorter processing times than the U.S. for many other immigration benefits, not just permanent residency—with the U.K., again, being the fastest.

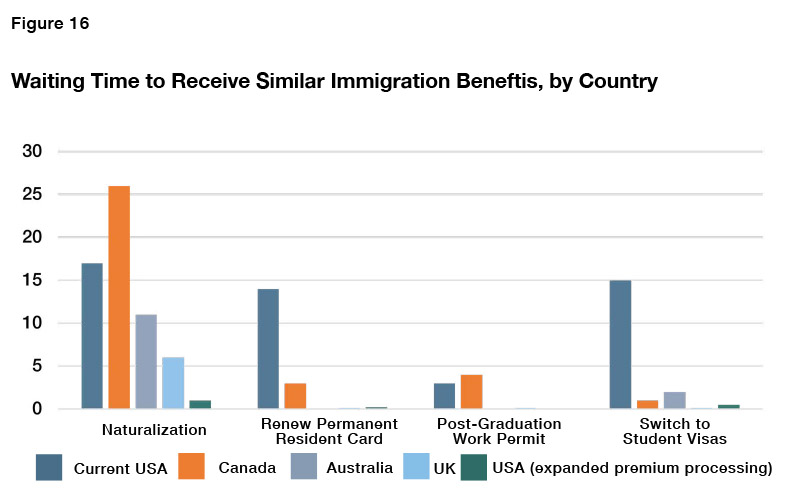

Expanding premium processing and ending the use of form I-765 for most applicants would put us ahead of Canada and Australia, and even the U.K., when it comes to renewing or obtaining many immigration benefits. As shown in Table 5 and Figure 16, these reforms would shorten the wait for naturalization applications from over a year to just 30 days and renewal of permanent resident cards from over a year to just seven days. They would also allow those with other visas to obtain a student visa in just 15 days and would allow international students to receive work permits immediately upon graduation.

Conclusion

America’s immigration system penalizes immigrants who follow the law, by making them wait years in unnecessary bureaucratic procedures. We make it nearly impossible even for millionaire investors to come to the U.S. to create jobs and businesses. While we make the world’s brightest immigrants wait for months and years for a decision, other nations are jumping at the chance to welcome them through procedures that take just days or weeks.

America should have a legal immigration system that makes timely decisions, affirmative or negative, and minimizes paperwork and applications. This report outlines two solutions to achieve an efficient legal immigration system:

- Expand premium processing: allow immigrants to pay large additional fees to USCIS and require the agency to process all major immigration requests within 45 days, depending on the type of request.

- Reduce the use of form I-765: exempt all categories of legal immigrants eligible for employment authorization from filing form I-765 and instead use alternative methods of verification to prove employment eligibility.

These solutions have no cost to taxpayers and would make millions of immigrants who are entitled to work authorization immediately eligible without filing duplicative forms. They would also end the immigration backlog within four years and shorten processing for all immigrants, especially those with the largest potential lifetime economic contribution. This would benefit high-skilled legal immigrants and lead to increased tax revenue for both the federal and state governments as immigrants start working earlier than in the current system.

This report outlines a few other solutions that would make life easier for high-skilled immigrants and bring some common sense to our immigration system:

- Digitize more immigration procedures for high-skilled immigrants to reduce waste.

- Reinstate visa stamping inside the U.S. to reduce uncertainty for immigrants seeking to travel abroad and to reduce the pressure on some U.S. consulates.

- Expand automatic revalidation for high-skilled immigrants traveling to certain countries in order to reduce the number of immigrants seeking visa stamping, leading to shorter consular processing there and making travel easier for immigrants.

- Facilitate change of EB category so that immigrants stuck in the green-card backlog are able to change filing categories with more ease, at no cost, and save time for USCIS.

No matter what level of immigration one believes is ideal, USCIS should be able to handle those who are admitted as quickly and efficiently as possible. None of these solutions makes more green cards available to immigrants on an annual basis; they merely shorten the process to obtain them so that immigrants do not have to wait so long before working or starting a business. American media and politicians understandably focus on the crisis on the border but pay too little attention to how our legal system discourages the world’s entrepreneurs, innovators, and high-potential individuals from coming to the United States. Three-quarters of Americans of all partisan affiliations agree that we need a system that encourages more high-skilled immigrants to come to the U.S. and makes the process easier for them. And a key part of making the legal immigration process easier for high-skilled immigrants is to ensure that they and their families receive timely decisions.

About the Author

Daniel Di Martino is a PhD candidate in economics at Columbia University and a graduate fellow at the Manhattan Institute, where he focuses on high-skill immigration policy. Born and raised in Venezuela, he came to the U.S. in 2016. He has appeared many times on national TV, including Fox News and CNN, and has written for USA Today and National Review. Di Martino speaks regularly on college campuses and at high schools. He received fellowships from the Institute for Humane Studies and the Job Creators Network.

Endnotes

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).