A Budget Plan for the Next Mayor

Introduction

New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio took office amid an economic expansion and immediately increased spending—granting raises to tens of thousands of workers, adding new programs, and increasing the size of the city workforce by tens of thousands of new positions. He will leave office amid a titanic budget squeeze, thanks to the rapid growth of the city budget and the economic slowdown caused by Covid-19. It will be up to the next mayor to get the city’s budget back on stable fiscal ground.

This won’t be easy. New York is already one of the highest-taxed big cities in the country. There are widespread reports of residents, especially well-heeled ones, fleeing Gotham, making the prospects for further steep tax increases risky and probably counterproductive. But de Blasio’s spending spree has left room for cuts and realignment, if voters can elect a new mayor with the wherewithal to challenge the political forces that shape the city’s budget.

The Gathering Fiscal Storm

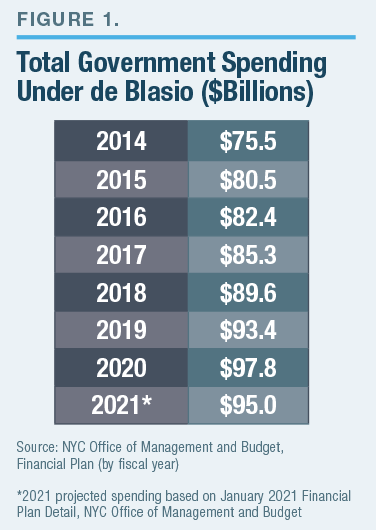

During his first seven years in office, de Blasio boosted spending by more than $20 billion, a growth of 30% until the pandemic hit (Figure 1).[1] Among the biggest bills that he left taxpayers was a series of huge pay increases for workers, including awarding workers with bonuses for work that they had done during the term of the previous mayor, Michael Bloomberg, who had balked at employee demands.

De Blasio’s first budget deal with unions, many of which had heavily supported him, gave them retroactive increases that stretched as far back as 2009—that is, five years before he took over.[2] He awarded teachers, for example, a 4% “pay” increase for the year 2009, another 4% for 2010, and then a bonus for 2011.[3] These pay raises, which came on top of the annual “step” increases that teachers get just for working additional years, added $4 billion to payroll costs over the life of the contract. By the time de Blasio was done negotiating with other unions, the increases helped spur rapid increases in budget growth—by $5 billion his first year in office.[4]

De Blasio’s first budget deal with unions, many of which had heavily supported him, gave them retroactive increases that stretched as far back as 2009—that is, five years before he took over.[2] He awarded teachers, for example, a 4% “pay” increase for the year 2009, another 4% for 2010, and then a bonus for 2011.[3] These pay raises, which came on top of the annual “step” increases that teachers get just for working additional years, added $4 billion to payroll costs over the life of the contract. By the time de Blasio was done negotiating with other unions, the increases helped spur rapid increases in budget growth—by $5 billion his first year in office.[4]

Bloomberg had refused to agree to new union contracts because he was seeking savings from the unions in areas such as health benefits. At the time, these costs were already stratospheric, and they’ve only continued increasing rapidly. New York City, virtually alone among big cities these days, pays almost the full cost of health care for city workers and retirees. The benefits promised to retirees for health care amounted to more than $100 billion in future costs that the city hadn’t funded.

During the de Blasio years, that debt increased by more than $25 billion as the city continued to promise workers cost-free health care in retirement without putting aside the money to pay for it. Spending for retiree health care has grown to more than $2.5 billion annually, which must be paid from the city’s everyday budget.[5] Combined with the future benefits owed to current workers— which are increasing every year by another $5 billion that the city isn’t saving for—future taxpayers, as well as mayors, face a grim future.

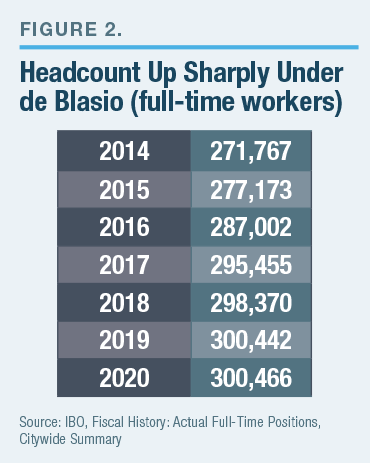

Even as pay increases and benefit costs made the price of employing the average worker soar, de Blasio sharply increased the size of the city’s workforce. Under his administration, the number of employees working for the city, including full-time workers and full-time-equivalent positions, has reached an all-time high: an increase of nearly 29,000 positions, or 11% (Figure 2).[6]

Even as pay increases and benefit costs made the price of employing the average worker soar, de Blasio sharply increased the size of the city’s workforce. Under his administration, the number of employees working for the city, including full-time workers and full-time-equivalent positions, has reached an all-time high: an increase of nearly 29,000 positions, or 11% (Figure 2).[6]

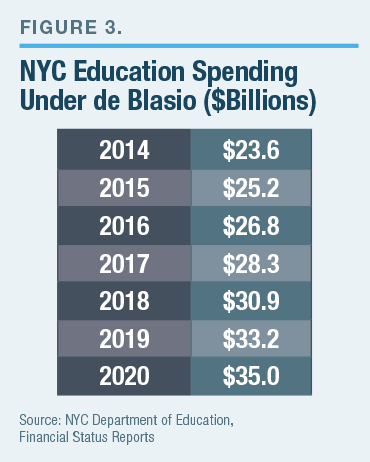

Among the areas where employment leaped the most is the school system, whose ranks have swelled by more than 13,000 positions, or 11%, because of growth in teaching positions as well as administration.[7] Those gains have spurred a nearly 50% rise in the schools’ budget, to $35 billion (Figure 3), a compound annual growth rate of almost 7%. The cost of salaries, fringe and other benefits, during de Blasio’s time in office, has risen $4.5 billion.

Other big areas of growth include mental health services, spurred by the mayor’s ThriveNYC program, which dedicated several hundred million dollars a year in new spending. Personnel rolls in the city’s health and mental hygiene department increased by 29%; children’s services staffing rose by 20%.[8]

Other big areas of growth include mental health services, spurred by the mayor’s ThriveNYC program, which dedicated several hundred million dollars a year in new spending. Personnel rolls in the city’s health and mental hygiene department increased by 29%; children’s services staffing rose by 20%.[8]

Meanwhile, despite booming tax revenues for much of the last eight years, the city’s total bonded debt has increased by over $17 billion since the start of de Blasio’s tenure.[9] Annual debt service—i.e., the cost of paying off the city’s bonds—is scheduled to rise in four years by $2.9 billion, to $9.3 billion.

These numbers are part of what is helping put so much pressure on the city budget since New York’s economy began to shut down in mid-March 2020. In June 2020, the city passed the fiscal year 2021 budget (which began on July 1, 2020), which the mayor downsized (from the $95.3 billion that he said he wanted to spend) to $88 billion, though the latest city financial plan shows New York again on track to spend $95 billion this year. But the budget contains numerous short-time, one-shot reductions, and it swipes money largely from reserve accounts to balance the budget, leaving big questions about the future.[10]

Indeed, of the nearly $9 billion hole punched in the city’s revenue by the pandemic, expense cuts closed only half the deficit. Those included killing certain programs such as residential composting, unspecified labor savings (such as some $336 million in NYPD overtime costs that it is unclear the city can achieve), and realizing savings from a reduction of services in a city that’s been partially closed for much of the last half-year.[11]

Tellingly, the city is also using some $4 billion in reserve funds to close the gap. About $1 billion comes from reserve funds built up in years when tax collections exceeded expenditures, but another $2.6 billion is taken from the city’s retiree health-benefits fund, which New York is supposed to be saving to pay for future health benefits of current workers. To be sure, the city has made a practice over the years of using money set aside for health benefits to close budget gaps during recessions, which is one reason that New York has a giant unfunded liability. Notably, the city has achieved little in the way of savings through better or more efficient operations.

Because the city has done little to reduce costs over the long term, New York faces bigger deficits in the years beyond 2021. In his proposal for next year’s budget (FY 2022, which begins on July 1, 2021), de Blasio outlined $92.3 billion in spending and projected a $5.25 billion deficit that would have to be eliminated.[12]

The state’s Financial Control Board (FCB), whose job it is to audit the city’s finances, looked at Gotham’s new budget and identified significant risks that the board thinks will exacerbate coming budget gaps. The board focused on the “unspecified” savings that the city must negotiate with labor unions, as well as hundreds of millions of dollars in overtime costs that the city hasn’t previously been able to control but now says that it will cut. As a result, the FCB estimated that there's still a $300 million budget gap in fiscal year 2021, which began on July 1, 2020, and that the city's budget gap in 2022 rises to $5.4 billion in 2022, $4.5 billion in 2023, and $4.7 billion in 2024. “Plans need to be developed now to deal with the risks, not just in the current fiscal year but, more importantly … to deal with the growing outyear gaps,” the board said. “The city must develop a multi-billion dollar plan, with recurring savings.”[13] A recent report by the city’s Independent Budget Office (IBO) projects smaller deficits, rising to $2.3 billion in 2023, though the report also cautions that New York faces substantial economic risks that could exacerbate those numbers, as did FCB in its report.[14] Although the city and its school system will receive billions of dollars from the recently passed federal stimulus bill, projected future deficits are so large that the next mayor will still have to work hard to balance New York City's budget.

Recommendations

• Accelerate the PEG (Program to Eliminate the Gap).

De Blasio has seemed indifferent to the idea of increasing the efficiency of city government as a way to bank savings. Early on, he ended a program that had stretched over four mayors for more than three decades. Known as the Program to Eliminate the Gap, or PEG, it consistently challenged all city departments to find savings that eliminated projected future budget gaps as they became apparent.[15] PEG required all departments to participate in a constant reevaluation of their spending. Although the savings could often be small, such as paring back outside contracting or reducing spending on marginal items like food services, the sustained momentum of PEG helped accumulate substantial sums—as much as $24 billion during 2010–13, according to one study.[16]

De Blasio replaced PEG with a voluntary effort that has garnered much smaller savings generated by fewer city agencies. Much of the savings that the mayor has claimed arose from reestimating expenditures and declining debt-service costs, thanks to favorable interest rates. Less than 20% of projected reductions have come from the city operating more efficiently. Though de Blasio reinstated PEG last year, it will be up to the next mayor to ensure that PEG becomes a priority again.

• Bring the cost of health care for employees and retirees in line with costs in other governments.

The city pays the entire cost of health premiums for more than 95% of the workforce. It similarly pays for generous retiree health care with little or no contribution by retirees—something that is rare in both the public and private sector. This has made New York City government uncompetitive from a cost perspective with other big cities around the country, allowing them to operate with lower taxes. A big part of retiree health costs consists of full insurance benefits for workers (and their spouses) who retire before the age of 65. After they reach 65, workers join Medicare, but the city reimburses them for Part B premiums and the premiums for Medicare supplemental insurance.[17]

These costs are especially onerous in public safety departments, where there are more retirees than active workers. In essence, the city subsidizes full insurance benefits for the equivalent of two full workforces. The overall bill for retiree health care alone has reached $2.25 billion annually. The next mayor needs to press for more cost-sharing. Worker health-care expenditures alone are slated to rise by 25%, or nearly $3 billion, over the next four years, according to the city comptroller’s office.[18]

A study by the Citizens Budget Commission of other government workers in cities, states, and the federal government found that cost-sharing of premiums is now widespread for workers and retirees.[19] Having New York City workers and retirees contribute 10% toward their health-insurance premiums—less than the average for big employers these days—would save more than $500 million a year, the city’s IBO estimates.[20] Requiring early retirees to pay half their health-insurance premiums would reduce annual spending by $420 million, and having those on Medicare contribute half the Part B premium saves another $148 million. Retirees also get unprecedented full coverage for their spouses, at enormous cost. Reducing the subsidy for these premiums by half would save hundreds of millions more. Virtually all these reductions involve benefits where New York City provides far more subsidies than most other public-sector employers. The cuts simply bring the city into line with other big cities, at huge savings.

• Bring city pension costs in line with state costs.

The city has experienced rising pension costs over the past 20 years because New York’s defined benefit system places enormous potential liability on taxpayers, who must make up shortfalls in investment returns within pension fund portfolios. The state constitution prohibits the city from altering the terms of pension plans for current workers. Nevertheless, New York City can institute reforms that would, over time, make its pension system affordable. One way to proceed is by offering employees more options, specifically a 401(k)-style, defined contribution plan that offers flexibility and portability to workers, and/or a hybrid plan that creates a combination of a small defined benefit plan with a tax-free defined contribution plan.[21] The state already offers a defined contribution plan for employees at the State University of New York system, administered by TIAA-CREF, and up to three-quarters of professors at the SUNY campuses have opted in to the plan.[22]

A survey undertaken by the Empire Center found that 26% of New York State’s public school teachers would favor the defined contribution plan, and 57% would consider opting for a hybrid model.[23] One reason is that a large percentage of teachers change jobs over time, often losing a substantial part of their pension benefits as a result because defined benefit plans make few contributions toward pensions until teachers have spent a decade or longer in the system. Contributory models, which make steady yearly contributions toward retirement accounts, are far more appealing to employees who might want to take their benefits elsewhere if they change jobs. Defined contribution plans work especially well for younger employees, who tend to be more mobile and hence benefit more from portability. Such a move would spur long-term city savings.

On average, public sector-employers contribute about 5% of salaries to defined contribution retirement plans.[24] By contrast, the $10 billion annually that New York City is currently spending represents contributions that are 33% of salaries; and there is every likelihood that those costs will rise higher if the pension funds do not hit their long-term investment goals.[25]

• Reduce the size of the workforce through cuts, attrition, and productivity gains.

Increased employee compensation during the de Blasio years has accounted for nearly half the total rise in the city’s budget under his administration.[26] The rise in this budget item has come not just from salary increases but also from a robust hiring spree. In his recent budget proposal, de Blasio promised to use PEG to eliminate 7,000 to 12,000 city positions through attrition. However, that would still leave New York’s workforce far larger than when he took office. New programs account for much of the growth. ThriveNYC, a mental health initiative under the supervision of the mayor’s wife, is a favorite program of de Blasio but of dubious value and highly criticized for focusing on nebulous mental health problems of the general population rather than providing effective services for seriously mentally ill people.[27] A smaller, more focused, program using already-existing resources could save the city hundreds of millions of dollars annually.

The mayor’s other signature initiative was a universal prekindergarten program, originally supposed to benefit children of low-income households. De Blasio extended it to all households, at a cost now approaching $1 billion a year, because, he said, it was a matter of equity. The program was originally designed for four-year-olds; de Blasio is expanding it to three-year-olds. Though the state-funded much of the original program, the city now pays about half the cost and has been financing much of its recent growth, even as the state, facing its own budget problems, is cutting appropriations to the city.[28]

In addition to downsizing programs of doubtful value, the new mayor needs to look at making the workforce more productive. City employees typically work 35–37.5 hours a week. Increasing that to 40 hours a week would provide a different way of racking up labor savings and reducing the size of the workforce. To avoid layoffs, it would, over time, allow the city to decrease its workforce through attrition. Over three years, IBO estimates, those savings would rise to over $750 million annually.[29]

• Accelerate the privatization of the NYC Housing Authority (NYCHA) and explore other avenues of privatization to boost investment in the city.

Early in his tenure, de Blasio dismissed any efforts to spur private investment in the city and save money through privatization— i.e., the process of selling government property or other assets to private companies or contracting city services to outside enterprises—a strategy that many municipal governments use to save money. However, the mayor has been forced to consider privatization as a means of bailing out the deeply indebted NYCHA, which, through years of mismanagement, has accumulated some $40 billion in necessary repairs and capital work.[30]

Today, the city’s plans include leasing open space in housing projects to private developers, selling air rights over housing projects, and converting about 60,000 apartments in public housing to private management. The current chairman of NYCHA, Greg Russ, has said that he wants to explore further privatizations to raise even more money as the bill for fixing public housing grows. The next mayor should certainly retain Russ and endorse new efforts. A Manhattan Institute study identified significant commercial opportunities for further development on housing authority property.[31] Such moves will not only bring more money into government coffers but will also increase private investments and services into local neighborhoods.

It took a grave emergency for the city to resort to private sources for NYCHA. Now the entire city budget faces a similar emergency, and it is logical for New York to look closely at other opportunities for privatization. Many municipalities across America, for example, have privatized residential trash collection. Previous studies have estimated that the city could save hundreds of millions of dollars by competitively bidding out its trash collection and employing other productivity savings.[32] New York’s next mayor could begin demonstration projects with private carters in selected neighborhoods to evaluate best practices and get accurate calculations on the savings. Former mayor Rudy Giuliani initiated such a program in the early 1990s but failed to aggressively pursue it after unions representing sanitation workers agreed to money-saving concessions. It is time to reconsider this strategy. A privatization commission could examine where it would work best.

• Ask the state to invoke the Financial Control Board to make cost-cutting easier.

New York State’s union-friendly laws make it difficult for mayors to cut benefits for workers once they’ve been granted—largely because even after a contract expires, current benefits stay in place. That gives union leaders an incentive simply to refuse to negotiate with a mayor who seeks worker concessions.[33] However, during the city fiscal crisis of the 1970s, the state created an oversight entity, the Financial Control Board, to monitor city budgets. FCB has the power to take control of city finances and impose money-saving measures.[34] It’s a strategy that the next mayor should consider asking Albany leaders to invoke. Without the board’s power, the unions’ incentive is to stand pat.

Salaries and benefits today constitute over half of New York City’s entire budget. Without the ability to reduce those costs— because of state restrictions on altering already-negotiated union contracts with workers—it will be impossible for the next mayor to balance the city’s budget without such deeply extensive and widespread layoffs that they will hamper New York’s ability to deliver services. The goal should be, instead, to find the best ways to achieve cost reductions that maintain essential services. To do that, the city needs FCB to suspend state laws that make changes to union contracts impossible to achieve.

Conclusion

A recent Manhattan Institute survey found that more than four in 10 residents said that they would like to leave the city to live elsewhere.[35] That same poll found that more than half of residents thought that services in the city were not worth the amount they paid in taxes, and 75% said that they approved of lowering taxes as one strategy to help revive the city. At the same time, 51% of residents endorsed limiting the collective bargaining rights of city workers to address budgetary problems, while only 25% opposed that as a strategy for helping balance the city’s budget.

The next mayor faces a fiscal crisis unlike any the city has seen since the months after 9/11. The difference is that resolute New Yorkers then pulled together to save their city, and they collectively valued a strong police department and civic order. Now, however, the city faces potentially serious long-term trends, including a widespread move among high-income taxpayers to remote work, a decline in civic order, and a continuing fear of infectious disease as a disincentive to city living. New York’s next mayor needs to understand that city government can’t sustain itself for very long under these conditions unless it significantly changes how much money it spends and why it spends it.

Endnotes

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).