The Social Construction of Racism in the United States

Foreword

by Coleman Hughes

In the 1980s, people all around America became convinced that day care centers were secretly practicing demonic ritual sex abuse on children. These allegations stayed in the national news for the better part of a decade. Hapless day care workers were falsely convicted of running sex rings. Evidence of their guilt was manufactured as necessary. In hindsight, this episode looks absurd. How could anyone have believed that there were Satanic day care centers throughout the country? Yet at the time, many reasonable people were swept up in the delusion—as were the prosecutors and elected officials who promised to put a stop to the fake problem. Such is the nature of moral panics. What looks like obvious absurdity from the outside seems totally reasonable to those on the inside.

Some moral panics are mysterious in origin. Others are the product of specific ideas. Since about 2014, we have been facing a new moral panic surrounding race, gender, and sexuality. Unlike Satanic day cares, this one is not a complete fabrication. Bigotry is real. Yet the public perception of bigotry has surpassed the reality to such an extent that it has become a moral panic. White supremacy is said to be rampant. Black people should fear for their lives when going for a jog, one New York Times op-ed argued.

Yet as political scientist Eric Kaufmann lays out in this paper, the public has a mistaken perception of how much racism exists in America today. This misperception is not only driven by cognitive biases such as the availability heuristic, it is also driven by ideas. Critical race theory and intersectionality—formerly confined to graduate seminars—have seeped into corporate America and Silicon Valley, as well as into many K–12 education systems. With their spread has come an increase in the misperception that bigotry is everywhere, even as the data tell a different story: racism exists, but there has never been less racism than there is now.

If America’s racial tensions ever heal, it will be because we were able to align our perceptions with our reality and leave moral panics at the door.

Executive Summary

This paper begins with a version of Tocqueville’s paradox:[1] at a time when measures of racist attitudes and behavior have never been more positive, pessimism about racism and race relations has increased in America.

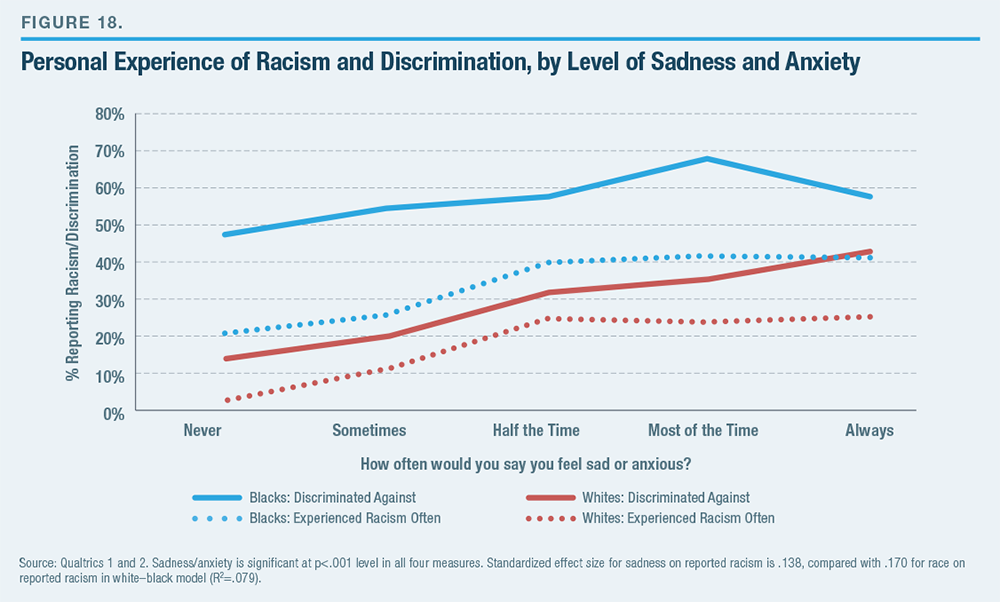

Why? An analysis of a wide variety of data sources, including several new surveys that I conducted, suggests that the paradox is best explained by changes in perceptions of racism rather than an increase in the frequency of racist incidents. That is, ideology, partisanship, social media, and education have inclined Americans to “see” more bigotry and more racial prejudice than they previously did. This is true not only regarding the level of racism in society but even of their personal experiences. My survey findings suggest that an important part of the reported experience of racism is ideologically malleable. Reports of increased levels of racism during the Trump era, for example, likely reflect perception rather than reality—just as people have almost always reported rising violent crime when it has been declining during most of the past 25 years. In addition, people who say that they are sad or anxious at least half the time, whether white or black, are about twice as likely as others to say that they have experienced racism and discrimination.

None of this means that racism is an imaginary problem. However, efforts to reduce it should be based on strong empirical evidence and bias-free measures. The risks of overlooking racism are clear: injustice is permitted to persist and grow. Yet there are also clear dangers in overstating its presence. These go well beyond majority resentment and polarization. A media-generated narrative about systemic racism distorts people’s perceptions of reality and may even damage African-Americans’ sense of control over their lives.

Key Findings Include:

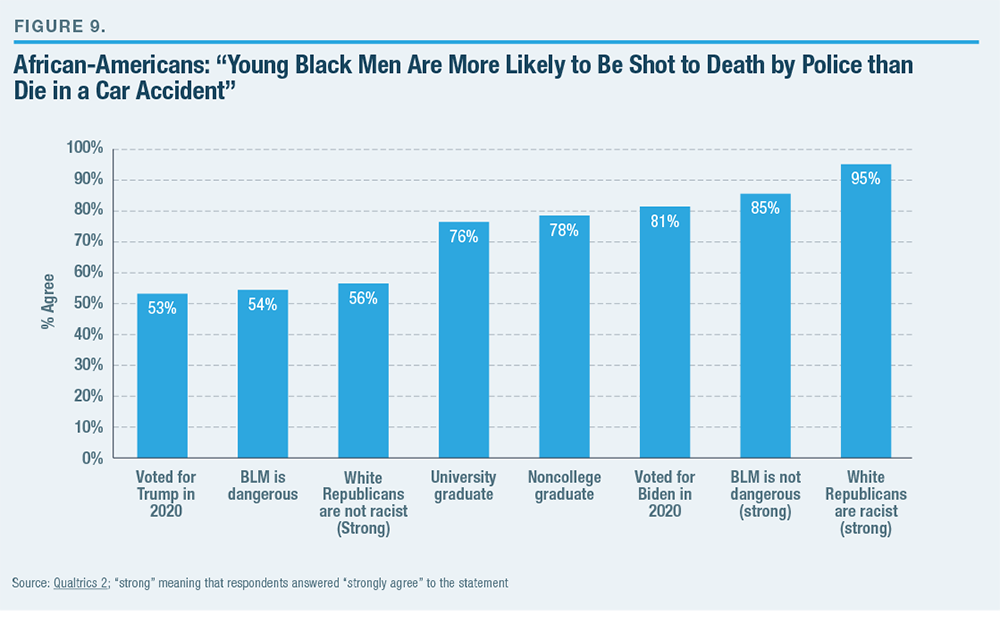

- Eight in 10 African-American survey respondents believe that young black men are more likely to be shot to death by the police than to die in a traffic accident; one in 10 disagrees. Among a highly educated sample of liberal whites, more than six in 10 agreed. In reality, considerably more young African-American men die in car accidents than are shot to death by police.

—Black Trump voters are almost 30 points more likely to get the question right than black Biden voters.

—Conservative whites are almost 50 points more likely to get it right than liberal whites.

—African-Americans who strongly agree that white Republicans are racist are 40 points more likely to get the question wrong than those who strongly disagree that white Republicans are racist.

- Black Biden voters are twice as likely as black Trump voters to say that they personally experienced more racism under Trump than under Obama. Black Trump voters reported a consistent level of racism under both administrations. Black respondents who strongly agree that white Republicans are racist are 20–30 points more likely to say that they experience various personal forms of racism than African-Americans who strongly disagree that white Republicans are racist.

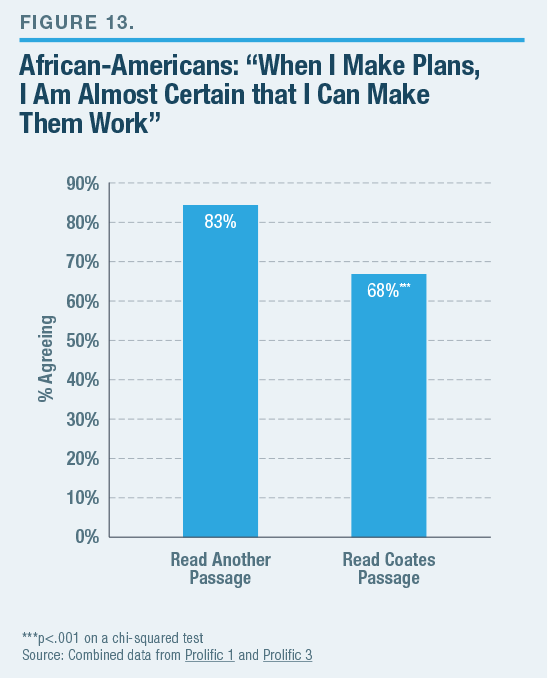

- Reading a passage from critical race theory author Ta-Nehisi Coates results in a significant 15-point drop in black respondents’ belief that they have control over their lives.

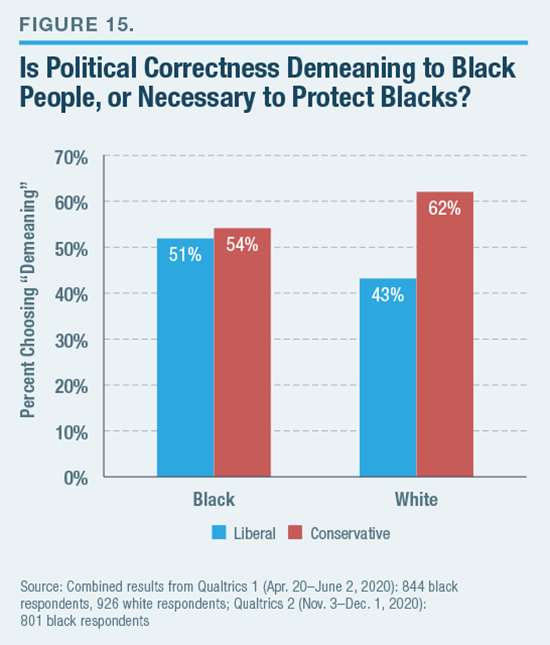

- A slight majority of African-Americans and whites overall felt that political correctness on race is demeaning to black people rather than necessary to protect them. Among blacks, the difference between liberals and conservatives was 3 points (51% of the liberals thought it was demeaning vs. 54% of the conservatives). Among whites, however, there was a nearly 20-point divide between liberals and conservatives (43% of the liberals thought it was demeaning vs. 62% of the conservatives).

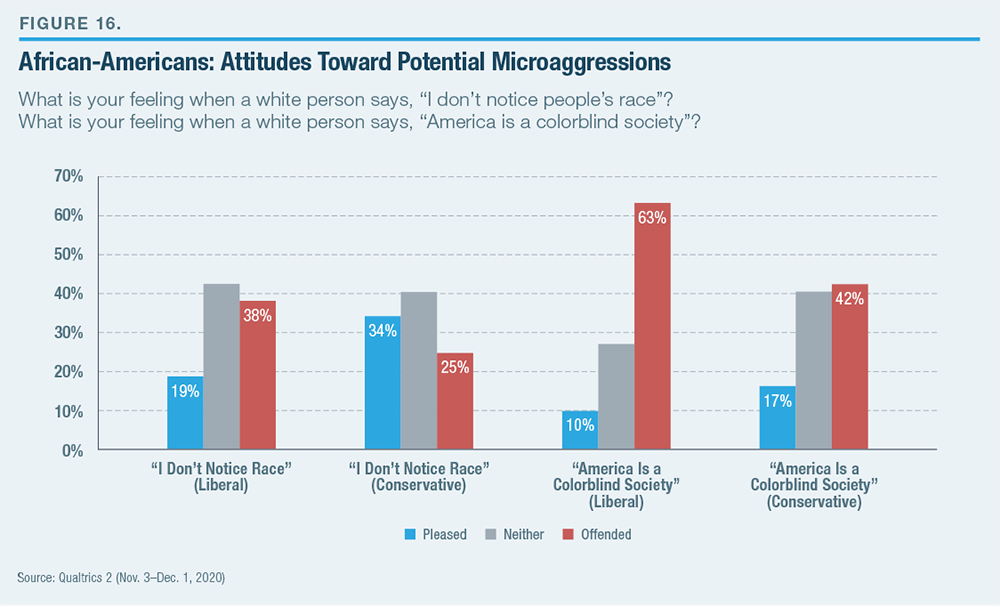

- Liberal African-Americans with a college degree are nearly 30 points more likely to find a statement by a white person such as “I don’t notice people’s race” or “America is a colorblind society” offensive than African-Americans without degrees who identify as conservative. Among whites, the gap between liberals and conservatives is 50 points.

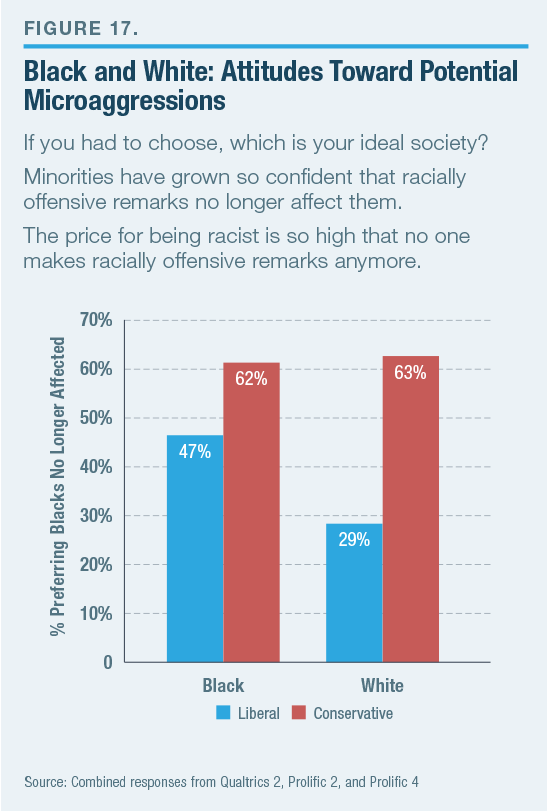

- When asked to choose between a future in which racially offensive remarks were so heavily punished as to be nonexistent and one where minorities were so confident that they no longer felt concerned about racial insults, black respondents overall preferred, by a 53%–47% margin, the resilience option. White liberals preferred the punitive option, by a 71%–29% margin; black liberals chose the second option by just 6 points, 53%–47%.

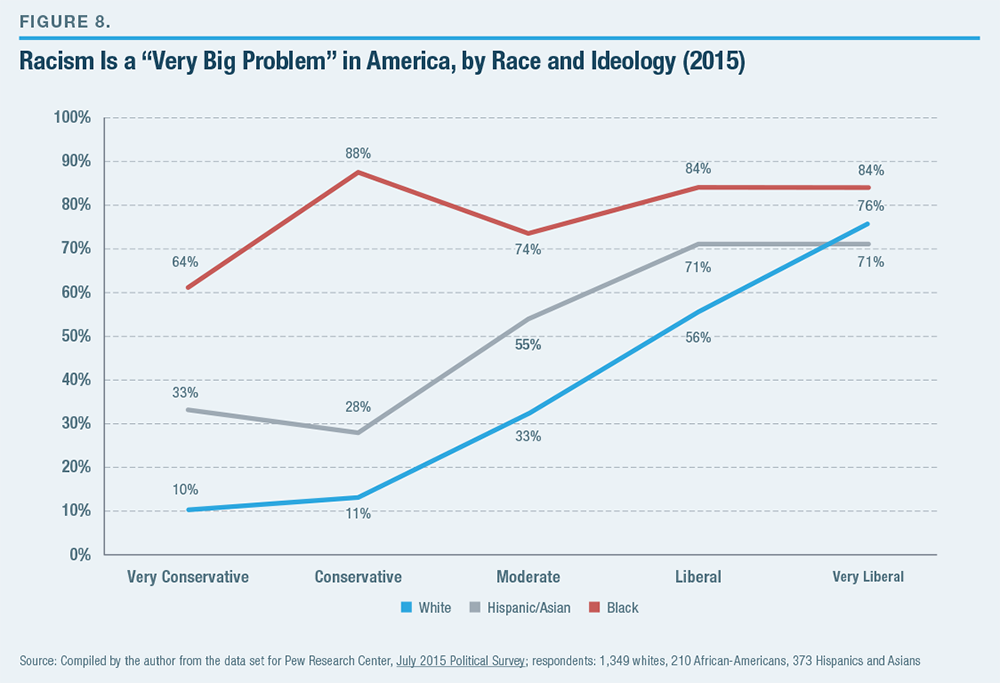

- In general, African-Americans’ opinion on race issues appears to be less affected by ideology and partisanship than white opinion. In a 2015 Pew survey, 20 points separated “very conservative” and “very liberal” African- Americans on whether racism is a very big problem. The gap between “very conservative” and “very liberal” whites was 65 points; the gap between “very conservative” and “very liberal” Hispanics and Asians was 40 points.

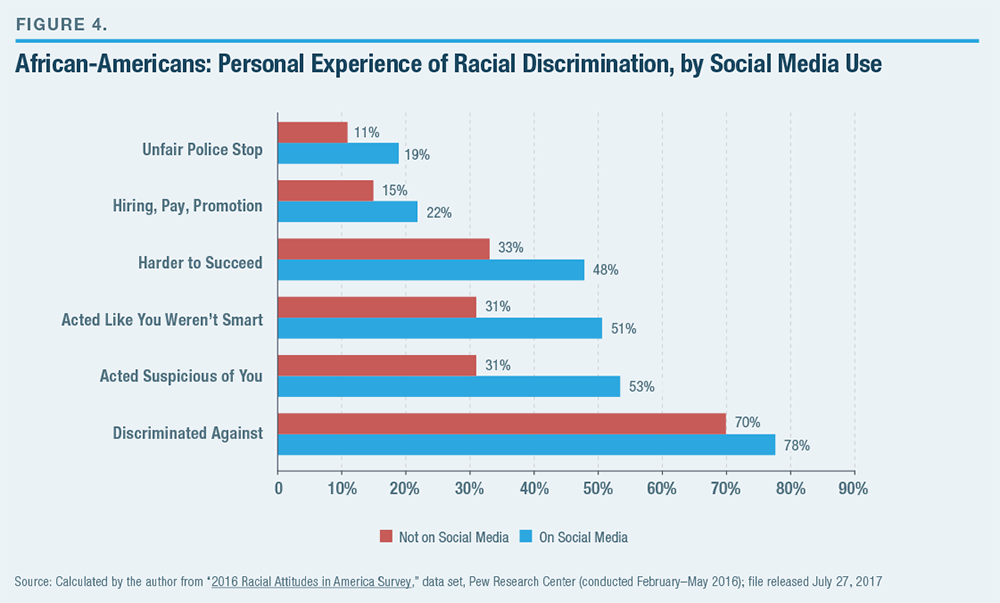

- Exposure to social media and other media appears to be related to survey respondents’ views of both the national prevalence of racism and their personal experience of it.

Introduction

Is racism real or is it, to some significant degree, socially constructed? While it is important to be skeptical of social scientists who overstate the malleability of categories like race, there is no question that perception does play a role in how people view social reality. This paper uses survey data to make the case that racism in America lies, in significant measure, in the eyes of the beholder. This not only concerns people’s perceptions of the prevalence of racism in society but even of their personal experience.

In their landmark work, The Social Construction of Reality, Peter Berger and Thomas Luckmann argued that the dominant ideology in society shapes the way people think about the social world, defining roles, norms, and expectations. Ideology is central to the social constructionist argument, defining right and wrong, and what constitutes a violation of moral “reality”; that is, the norms and social facts everyone “knows” to be true (even if they are not based on objective truth).[2]

The dominant ideology in today’s cultural institutions is what I have elsewhere termed left-modernism, a hybrid worldview that applies socialist theories of conflict to identity categories first developed by liberalism.[3] From liberalism comes the idea that majorities are often tyrannical while racial, religious, gender, or sexual minorities require protection. From socialism comes the notion that society is best understood as a struggle between oppressive and oppressed groups. Freudianism, with its focus on the subjective, has also shaped left-modernism through its focus on psychological sensitivity, which has fused with left-modernism’s outlook to produce demands not only for material but for therapeutic equality and safety.

Religions typically concentrate on a handful of totemic issues. For example, conservative Christian politics has, over time, focused on causes such as restricting the sale of alcohol, the teaching of evolution, or the provision of abortion. Left-modernism is instead centered around a trinity of totemic categories: race, gender, and sexuality. Race stands at the apex of the system, producing what John McWhorter concludes is a religion of antiracism.[4] For Jonathan Haidt, the sacralization of race, sexuality, and gender lies at the heart of the progressive worldview.[5] This means that it becomes difficult to objectively assess the scientific validity of claims made about disadvantaged identity groups, lest one transgress the sacred values of the ideology and even be perceived as having committed an act of blasphemy.

Moreover, racism itself is not a fixed term. While expanding the range of phenomena covered by a term like racism can make sense in some circumstances, we are arguably well past that point.

Given the prevalence of left-modernism in the elite institutions of society—universities, much of the media, large corporations, and foundations—there has been considerable cultural distortion in the definition of racism. Psychologist Nick Haslam calls the expanding meaning of clinical terms “concept creep,” which applies also to concepts such as bullying, abuse, trauma, and mental disorder. Left-modernism’s therapeutic ethos, combined with the centrality of race in its pantheon of sacred values, helps explain this “conceptual stretching” of racism.[6] For the writer Coleman Hughes, expanding the meaning of racism is part of an ideological project that seeks to heighten minority threat perceptions to underpin claims of harm that can justify silencing.[7] The endpoint of this logic is to criminalize such dissent as “hate.”[8]

The Media and Public Perception of Racism

It is well known that the media, with their ability to frame events and social trends, have an impact on public opinion. This is especially the case when it comes to the visibility and political prominence of certain issues, what political scientists call issue “salience.” For example, there is a close relationship in Europe between media coverage of immigration and salience—the number of people saying that immigration is the most important issue facing their country.

The same appears to be true for race. Gallup data show that the civil rights era of the 1950s and early 1960s, as well as the race riots in the late 1960s, saw the public salience of race spike (Figure 1). The public salience of race then remained muted until 1992, when the Los Angeles riots, in the wake of Rodney King’s beating, sent questions of race to the top of 15% of the public’s priority lists. Since 2014, a series of events (including the protests in Ferguson, Missouri, after the shooting death of Michael Brown by a police officer; and the election of Donald Trump) pushed the race issue above 10% salience. In 2020, despite the Covid-19 pandemic, the George Floyd/Black Lives Matter protests elevated race back to the top spot: it was named as the leading concern by nearly 20% of the public in mid-June 2020. This was the highest salience level recorded for race since the late 1960s, eclipsing the Rodney King spike.

Source: Frank Newport, “Race Relations as the Nation’s Most Important Problem,” Gallup, June 19, 2020

Source: Frank Newport, “Race Relations as the Nation’s Most Important Problem,” Gallup, June 19, 2020

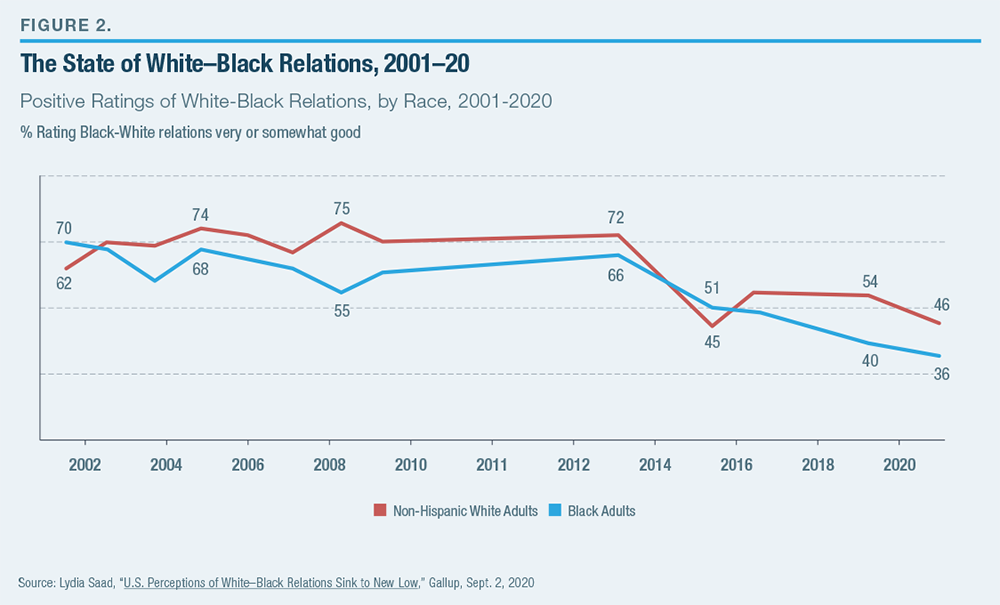

Media events affect the prominence of issues of race and racism in the public consciousness, but they also shape how people evaluate the quality of race relations. Other Gallup data show that during 2001–14, nearly 70% of Americans said that relations between whites and blacks were good. After the Ferguson protests, this fell to 47%, hovered in the low 50s between 2015 and 2019, and has since tumbled to 44% following the BLM protests (Figure 2).

Source: Lydia Saad, “U.S. Perceptions of White–Black Relations Sink to New Low,” Gallup, Sept. 2, 2020

Source: Lydia Saad, “U.S. Perceptions of White–Black Relations Sink to New Low,” Gallup, Sept. 2, 2020

The Decline of Racist Attitudes

The increasing pessimism over race relations stands in contrast to the steady, long-term liberalization among white Americans across a range of racial attitudes measured in the leading General Social Survey (GSS) since 1972. In the 1970s, for example, nearly 60% of white Americans agreed with the statement that blacks shouldn’t “push themselves where they’re not wanted.” This response had declined to 20% by 2002, when the question was discontinued. The share of white Americans who agree that it is permissible to racially discriminate when selling a home declined from 60% as late as 1980 to 28% by 2012.[9]

Approval of black–white intermarriage rose among whites from around 4% in 1958 to 45% in 1995 and 84% in 2013, according to Gallup.[10] In 2017, fewer than 10% of whites in a major Pew survey said that interracial marriage was a “bad thing,”[11] and, as Figure 3 shows, few now oppose a relative marrying someone of a different race. The actual share of intermarried newlyweds rose from 3% in 1967 to 17% in 2015.[12]

Approval of black–white intermarriage rose among whites from around 4% in 1958 to 45% in 1995 and 84% in 2013, according to Gallup.[10] In 2017, fewer than 10% of whites in a major Pew survey said that interracial marriage was a “bad thing,”[11] and, as Figure 3 shows, few now oppose a relative marrying someone of a different race. The actual share of intermarried newlyweds rose from 3% in 1967 to 17% in 2015.[12]

For decades, American National Election Studies (ANES) posed a question of whether minorities/ blacks should help themselves or whether the government should help them more. There was a gradual rise in support for government assistance to blacks during 1970–2016 of about a half-point on a seven-point scale.[13] Meanwhile, police killings of African-Americans declined by 60%–80% from the late 1960s to the early 2000s and have remained at this level ever since.[14] Racist attitudes and behaviors have sharply declined, though the problem has not been eradicated.

The Racism Paradox

The increasingly sour national mood on race relations in the U.S. may likely be related to the higher salience of race since the 2014 Ferguson protests. While it is too early to be definitive, the emergence and rapid spread of social media may account for this. Combined with smartphone citizen journalism, social media mean that knowledge of white-police-on-black-suspect violence is more likely to circulate widely, where it can ignite riots and boost the salience of the race question. Thus, even as the number of such incidents is declining, each event is more likely to be captured alive and to possess a higher media multiplier effect.

Evidence that social media may be shaping perceptions of racism is provided in Figure 4, which shows that black respondents on social media in 2016 were considerably more likely to report experiencing discrimination than those not on social media. This is a statistically significant effect that holds when controlling for age, education, income, partisanship, ideology, gender, and contact with whites. On questions about whether black people have experienced people acting suspicious of them or thinking that they are not smart, the gap between those on social media and those not on it reaches as high as 20 points.

People who care passionately about an issue (or see it flagged in the media) tend to overestimate its prevalence. For example, Americans and Europeans routinely overestimate the population shares of minorities, immigrants, and Muslims while underestimating the white share. In France, the average person in 2016 thought that the country was 31% Muslim; the correct answer was 7.5%. In the U.S. and Canada, the same survey shows that people estimated their countries to be 17% Muslim, compared with the actual 1% and 3%, respectively. Anti-immigration whites overestimate more than liberal whites.[15] Meanwhile, minorities tend to overestimate their share of the population more than whites do because they extrapolate from their locale to the nation. Black respondents in a 2005 survey said that the U.S. was 38% black rather than the actual 12%, and Hispanics said that the country was 39% Hispanic rather than 13%.[16]

In terms of racial discrimination, a 2019 study asked people how many résumés a black person would have to send out to get a callback from an employer if a white applicant gets one callback for every 10 applications. It found that Democrats thought that a black person would have to send 26 résumés to get one callback, while Republicans said 17. The correct answer was 15. Overall, blacks were not significantly more likely than whites to overestimate discrimination: partisanship, rather than race, is what apparently led to misperceptions.[17]

Perceptions about trends over time are somewhat more accurate. In Western Europe, for example, concern about immigration is connected to actual immigration levels over time and tends to rise when inflows are high.[18] But this is not always the case. In the U.S., crime rates were flat between 1989 and the mid-1990s, and then fell every year until 2019. Unmoved, a majority of Americans in every year but two since 1989 said that crime had risen over the past year. In 2019, 64% of Americans said that crime had risen in the previous year, even though it had actually continued its gradual post-1990s decline.[19] Emotive issues that feature in the news affect people’s perceptions of the size of a problem.

The Great Awokening

Videos of interracial violence circulate on social media; yet this has not led to noticeably cooler feelings between America’s racial groups in ANES surveys.[20] Something distinctive has changed with respect to perceptions of racism since 2014 that cannot be explained solely by technological change.

Ideological shifts are an important independent factor to investigate when trying to explain the racism paradox. At the U.S. state level, Google searches for “racism” are highly correlated with searches for “sexism,” which is, in turn, correlated with the Democratic share of the vote. Liberal states such as Vermont tend to come out highest on both indices, while southern and mountain states score lowest. Searches for “racism,” in short, serve as a useful barometer of left-modernism.

While the salience of racism fluctuates with events, the use of the term “racist” and “racism” has increased in three waves since 1960. Figure 5, based on big data from Google’s Ngram Viewer, tracks the popularity of terms in English-language books. It shows that the use of the term “racism” first rose sharply in the late 1960s, a time of New Left student activism. After reaching a plateau, it surged again and rose to a new level in the late 1980s and early 1990s, when political correctness and speech codes came into vogue. Then, around 2014, there was another upsurge, in tandem with the current period of left-modernist ferment. The use of terms such as racism (or racist/s) took off especially sharply in left-leaning media outlets such as Vox and the New York Times.[21]

A 2018 report, “Hidden Tribes: A Study of America’s Polarized Landscape,” published by More in Common, found that “Progressive Activists,” who make up 8% of the U.S. population, are 3.5 times more active than the “exhausted majority” two-thirds of the population in posting political content on social media.[22] While the rise of social media, citizen journalism, and a surge in online partisan websites has been associated with what Matthew Yglesias calls the “Great Awokening,” it is not associated with right-wing populist voting, which is stronger among older and less educated voters who use social media platforms less.[23] Many left-modernist ideas have older roots in critical theory, but technological change helped left-modernists organize and spread new moral innovations, such as “microaggressions,” or causes, such as gender recognition.[24]

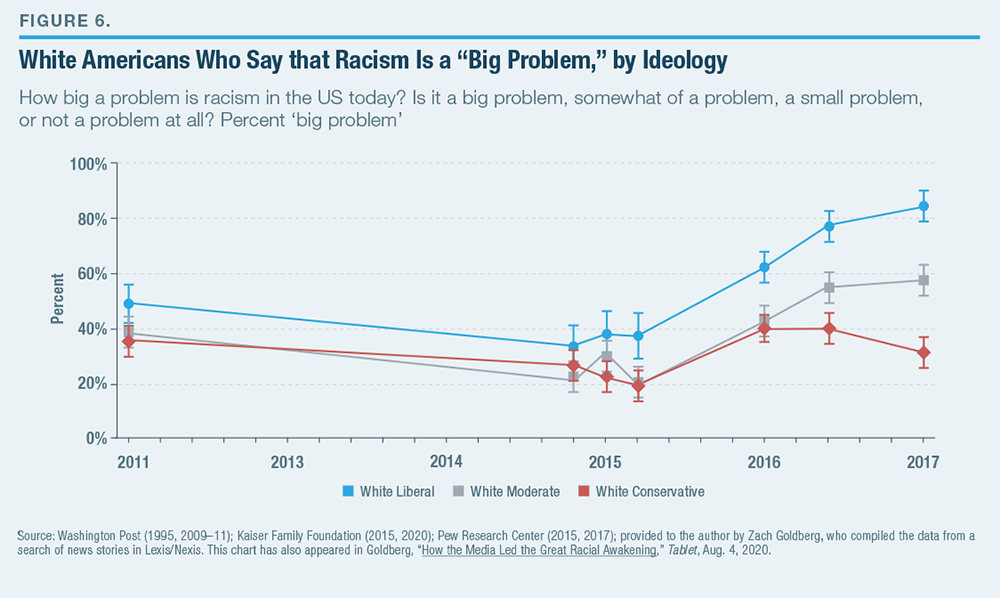

To what extent the most recent “Awokening” would have occurred in the absence of social media is an open question. Whatever the case, the Great Awokening has coincided with a large-scale shift to the left in attitudes toward questions of race, diversity, and immigration, especially among white liberals. Thus, partisanship and ideology increasingly affect perceptions of racism. The importance of ideological differences in perceptions of racism is shown in Figure 6, which reveals that among white conservatives, there has been little to no increase since 1995 in the share who think that racism is a “big problem.” White liberals show the greatest increase, with white moderates in between. The post-2014 trend (see Figure 2) of perceiving worse relations between whites and blacks is, therefore, less a reflection of statistical reality than of rising consciousness of racism, notably among liberals.

Defying Reality by Stretching Perception

The split between liberals and conservatives in their perception of racism in society indicates that an individual’s ideology shapes his estimate of the size of the problem. Racism thus contains an important socially constructed component.

There are important reasons that egalitarians may find it especially difficult to adjust their perceptions of racism to the reality of its decline. As Alexis de Tocqueville remarked almost two centuries ago in his classic Democracy in America:

In a similar vein, Coleman Hughes, in a pathbreaking 2018 essay, remarks on Tocqueville’s paradox as it concerns racial liberalism in America: “It seems as if every reduction in racist behavior is met with a commensurate expansion in our definition of the concept. Thus, racism has become a conserved quantity akin to mass or energy: transformable but irreducible.”[26]

Tocqueville’s and Hughes’s observations have now been confirmed scientifically as a variant of a wider phenomenon known as “prevalence-induced concept change.” This takes place when people reframe reality to conserve a concept into which they have been socialized. Citing work by Harvard University’s Daniel Gilbert, British psychologist Peter Hughes (no relation to Coleman) writes:

Black Public Opinion

Much of the evidence about perceptions of racism so far comes from national samples, which are dominated by white respondents. Though sample sizes for African-Americans in such surveys are typically small and there are fewer black-only surveys, it is apparent that black opinion is characterized by a weaker ideological divide than exists within white opinion. Data from Pew, for example, show that among blacks, 75% of liberals, but also 55% of the smaller group of conservative blacks, say that discrimination makes it harder for blacks to get ahead (Figure 7). By contrast, 17% of “very conservative” whites and 82% of “very liberal” whites agree. A modest 20-point partisan difference among blacks balloons to 65 points among whites. Since 2016, several surveys show that white liberals place to the left of minorities on questions of race, diversity, and immigration.[28]

There is also a substantially larger ideological gap among whites than blacks when it comes to viewing racism as a serious problem. Pew’s 2015 survey, profiled in Figure 8, found that “very liberal” whites evince nearly as much concern over racism (76%) as African-Americans, while moderate (33%) and conservative (11%) whites view racism as a much less important problem. The ideological slope is greatest for whites, with over 60 points separating conservatives from “very liberal” whites. The incline is less steep among Asians and Hispanics and gradual among blacks, with “very liberal” and “very conservative” blacks only differing 20 points in their assessment that racism is a very big problem (64% vs. 84%).

Are White Republicans Racist?

Another way to appraise how partisanship can skew perceptions about race is to compare white and black responses to the “white Republicans are racist” and “white Democrats are racist” questions fielded in a survey that I conducted on Qualtrics during April 20–June 2, 2020 (see below, Original Surveys Conducted for This Report).

Original Surveys Conducted for This Report |

Qualtrics (Qualtrics 1) Apr. 20–June 2, 2020 Qualtrics 2 Nov. 20–Dec. 1, 2020 Prolific Academics (Prolific 1) July 4–5, 2018 Prolific 2 June 15, 2020 Prolific 3 Nov. 26–Dec. 10, 2020 Prolific 4 Dec. 1, 2020

*Qualtrics is a survey firm that recruits survey participants according to demographic or other criteria specified by the client. A few firms, such as YouGov, maintain their own panel of users who fill out their surveys for a fixed rate. Qualtrics participants are recruited from market research companies and online, and they are matched on age, gender, and region, in order to provide a reasonably representative sample. Like other survey firms, Qualtrics pays those who take its surveys. For more details, click here.

**Prolific Academic is an online survey platform that restricts clients to those who pay survey respondents more than minimum wage. Users advertise surveys at a fixed reward per survey, and the pool of eligible users can opt to take the survey for the wage listed. Prolific samples have not been matched to population characteristics. I use statistical modeling to control for age, education, gender, and other demographic characteristics when assessing relationships between questions. For more details, click here. |

Whites and blacks who self-identified as liberal were similar in their agreement that “white Republicans are racist” (64% of liberal blacks, 61% of liberal whites) and in their low level of agreement that “white Democrats are racist” (23% for black liberals, 21% for white liberals). The bigger racial difference was among conservatives, where 10% of white conservatives but 36% of black conservatives said that white Republicans are racist, a 26-point difference. When it comes to the statement “white Democrats are racist,” 38% of white conservatives agreed, but only 28% of black conservatives agreed.

Responses to this question among African-Americans, as will be explored below, are strongly associated with both national perceptions and reported personal experiences of racism.

Fatal Police Shootings

The likelihood of a young black man dying from a car accident is considerably higher than his being killed by police. Even among young men of all races being killed by police, shootings form only part of total killings.[29] Nevertheless, eight in 10 African-American respondents to the Qualtrics 2 survey (Nov. 20–Dec. 1, 2020) believed that young black men are more likely to be shot to death by the police than to die in a traffic accident.[30] Only one in 10 disagreed.

This belief, at variance with reality, is not the result of counting respondents who are unsure of the answer jumping one way: there is a “neither agree nor disagree” option, but it was chosen by only one in 10 people. Nor is it a matter of educational level. Among the survey’s noncollege graduates, 78% believe that police shooting are a more common cause of death than traffic accidents, but so do 76% of university graduates—only 14% of whom contest this view. Neither age nor the share of African-Americans in a respondent’s neighborhood significantly affected the results.

With regard to police shootings, however, political outlook did shape people’s perceptions of social reality. For example, Qualtrics 2 found that while 53% of the black Trump voters (64 individuals) believed that police shootings are the leading cause of death for young black men, 81% of black Biden voters (597 individuals) did so, a statistically significant and powerful difference (Figure 9). While education and age made no significant difference in the respondents’ answers to this question, partisan perceptions of racial attitudes played the most important role. Thus, 95% of African-Americans who “strongly agree” that “white Republicans are racist” (22% of the sample) say that police kill more young black men than cars do, while 56% of blacks who “strongly disagree” that “white Republicans are racist” say this.[31]

The fact that politics matters more than education or age indicates that ideologically motivated reasoning[32] plays a role in governing perceptions of how frequently young black men are shot to death by the police. On the other hand, the fact that 53% of black Trump voters still agreed with the statement tells us that this belief is widespread and not simply a function of ideology.

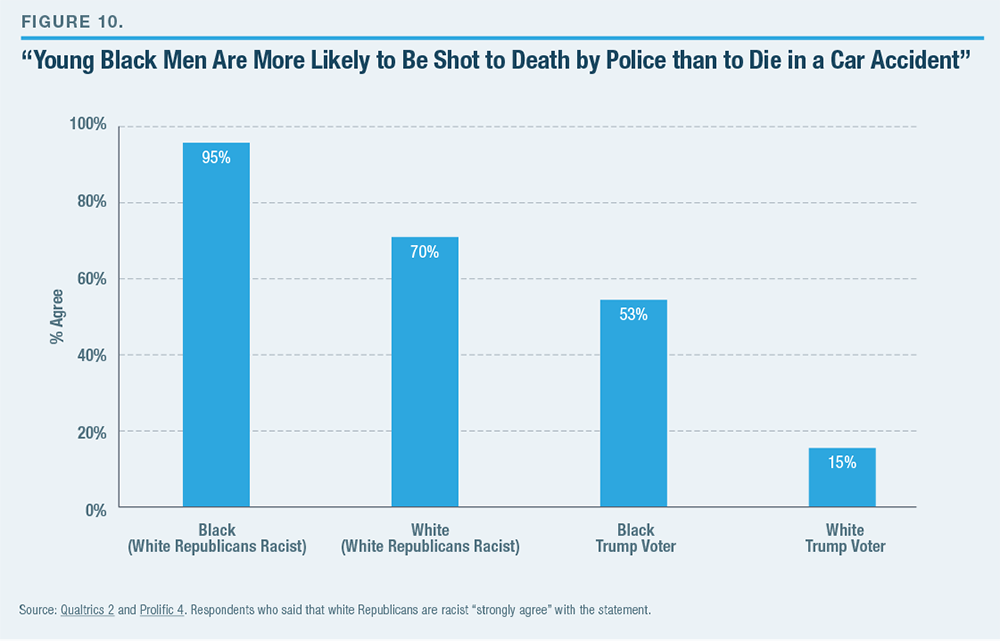

However, this perspective on an empirical question is not unique to African-Americans. Of the 391 white respondents in the Prolific 4 survey (Dec. 1, 2020), 70% of whites who “strongly agree” that “white Republicans are racist” also believed that young black men are more likely to be shot to death by the police than to die in a car accident (Figure 10). This is noticeably higher than the 53% of black Trump voters in Qualtrics 2 and vastly higher than the 15% of white Trump voters in Prolific 4 who believe this.

The gap between Trump and Biden voters on the question about fatal police shootings is 28 points among African-Americans (81%–53%) but 38 points among whites (53%–15%) in Prolific 4. Education level was not a significant predictor of accuracy on this question. These results echo those that recently found that only about a fifth of liberals but close to half of conservatives gave the right answer to a question on how many unarmed black men were killed by police in 2019. Fully 54% of “very liberal” Americans thought that more than 1,000 were killed compared with the actual figure of between 13 and 27.[33]

To be sure, African-Americans are more likely than whites to believe that the risk of young black men being shot to death by police is greater than dying in a traffic accident. However, ideology is about as important as race in influencing perceptions. Combining black and white responses to this question in Qualtrics 2 and Prolific 4, a person’s race predicts 25% of the variation in beliefs while ideology, the 2020 presidential vote, and a person’s view of whether “white Republicans are racist” predicts 29%.[34]

Figure 10 above compares data from two different samples, but Qualtrics 1 permits a comparison of blacks and whites on another question. That question was whether people agree or disagree with the statement, “White males kill more people than any other group in the United States.” In contrast to fatal police shootings, there is no clearly correct answer. While African- Americans commit slightly more murders than whites, the question could also be interpreted to encompass those who kill in other ways, such as through drinking and driving, in which case the statement is accurate. Results show that white liberals answer the question similarly to blacks (overall), with about half agreeing with the statement, while white conservatives diverge substantially, with 10% giving their assent.

The Social Construction of Personal Experience

Though politics doesn’t shape black opinion as much as white opinion, it remains the case that black views on national-level race issues also vary by ideology. The position of blacks as the traditional target of racial exclusion also means that focusing on black opinion can help us understand whether ideology affects people’s perceptions of having personally been the target of racism. This is, in many ways, a “harder” measure of reality than perceptions about racism in general because it concentrates on personal experience.

Figure 4 showed that the use of social media heightened black perceptions that others had acted in racially biased ways toward them. This suggests that part of the racism paradox may have to do with new peer-to-peer technologies. Ideology could also be a factor, inducing liberal African-Americans to read more racism into their personal interactions, or recall more racist incidents, than black conservatives do.

Looking at racism through the lens of social constructionism leads to a pair of testable propositions: first, that perceptions of whether one has experienced racism will be conditioned by ideology and partisanship; and second, that many minorities do not view socalled microaggressions as racist, while many whites who subscribe to left-modernist ideology do.

Personal Experience

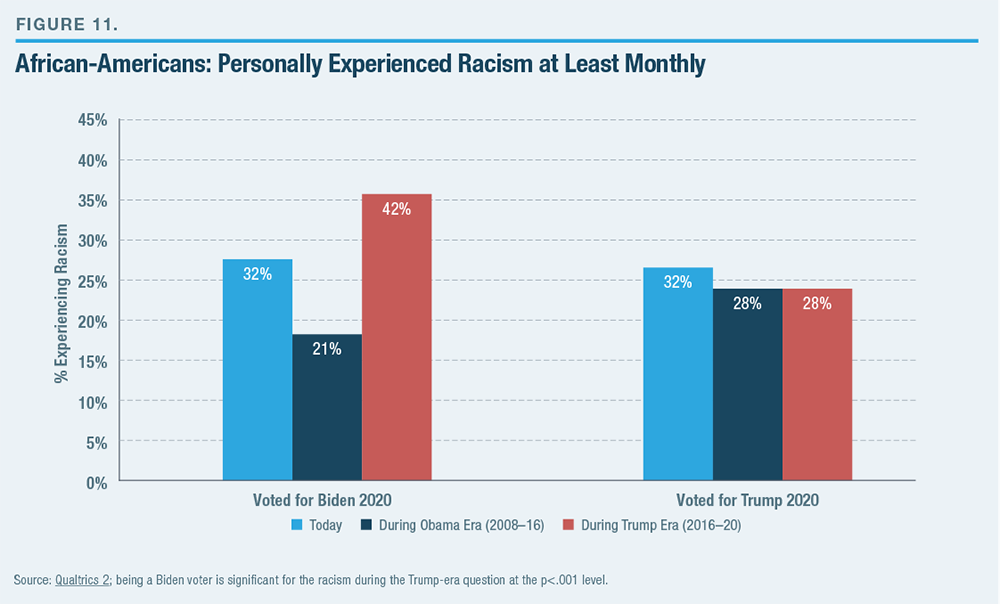

In order to assess whether partisanship affects people’s personal experience of racism, Qualtrics 2 asked African-Americans, “How often would you say that you experience racism in your daily life?”[35] A similar share of both Biden (32%) and Trump (30%) voters responded that they experienced racism on at least a monthly basis. These results were similar to Qualtrics 1, showing that 26% of black Biden[36] voters and 25% of black Trump voters reported experiencing racism on at least a monthly basis.

Much later in the 80-question Qualtrics 2 survey, I asked, “How often would you say that you experienced racism in your daily life during Barack Obama’s period in office, 2008–16?” I then asked the same question about experiencing racism “during Donald Trump’s period in office, from November 2016 until now.” Biden voters—the vast majority of the black sample— were twice as likely to say that they had experienced racism on at least a monthly basis (42%–21%) under Trump than under Obama (Figure 11).

Black Trump voters indicated a similar experience of racism under both administrations, but partisan prompts appear to have reduced personal reporting of racism among black Biden voters during the Obama years and increased it during the Trump years. The fact that Biden but not Trump voters deviated from their initial answer (when neither Trump nor Obama was mentioned) suggests that Democrats are largely responsible for changing their answers in response to partisan cues. The result is a partisan difference of 7 points in personal perceptions of racism during Obama’s administration and 14 points under Trump.

The partisan gap between black Trump and Biden voters of 7–14 points widens to 37 points when we compare black voters who “strongly agree” that “white Republicans are racist” with blacks who strongly disagree with this statement. Fully 56% of blacks who strongly agreed that “white Republicans are racist” said that they experienced racism under Trump, compared with 19% among blacks strongly disagreeing with the statement.

If racist behavior was actually higher under Trump, this should affect both groups of black supporters in equal measure. Moreover, we shouldn’t see a 10- point partisan difference between answers to the “how much racism do you experience” (answered in early November 2020) and “how much under Trump” versions of the question.[37] While it is possible that African-Americans who experienced more racism under Obama switched to Trump while those who encountered racism under Trump switched to Biden, this is a less convincing explanation than partisan motivated response bias. While black Trump voters may have a motive to underreport, the fact that their views align with their experience “today,” along with the fact that black Republicans tend to be moderate on race issues, suggests that political distortion is greater among black Democrats.

The extent to which personal and political perceptions of racism are connected can be glimpsed by comparing the reported personal experience of racism among left- and right-wing African-American respondents in Qualtrics 1 and 2. First, there is a liberal-conservative difference of 15 points in black people’s perceptions of whether there is a lot of discrimination against black people in America.[38] This is an understandable relationship, given the national data reviewed in the first part of this report and the expected links between ideology and the national problems that it frames.

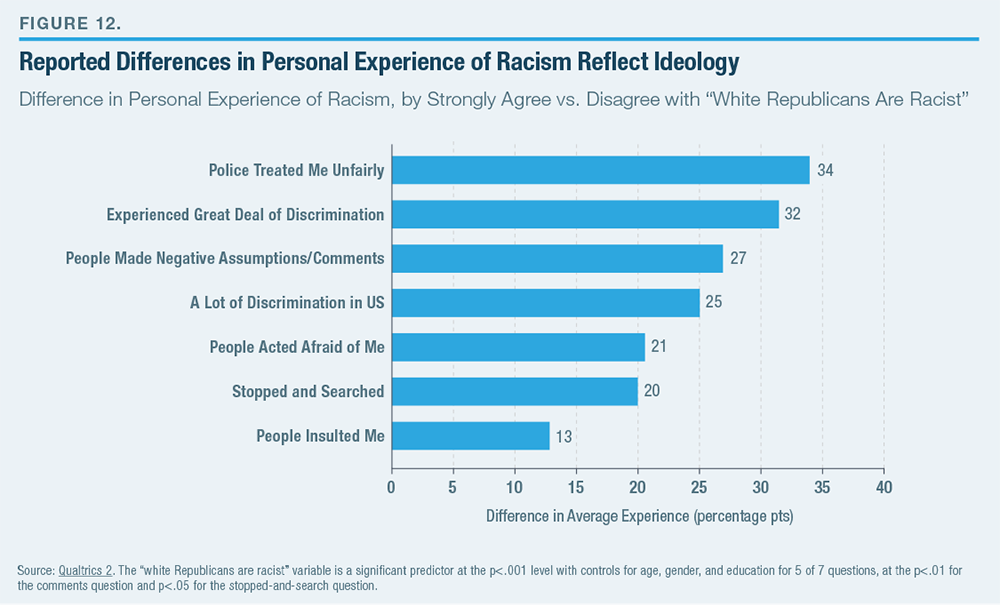

But it is surprising to see that ideological differences also appear in questions pertaining to personal experience. On four questions on the Qualtrics surveys mainly using wording from a 2017 NPR survey[39]—people making negative comments or assumptions about you, acting afraid of you, police treating you unfairly, and being stopped and searched—my analysis of the data shows an ideological divide within black America of 16–20 points when comparing those in the two liberal and two conservative categories on a 5-point liberal- to-conservative scale. In almost all cases, the results are statistically significant controlling for age, gender, education, and the share of African-Americans and holders of advanced degrees in a person’s zip code.

These results accord with other findings. In the 2018 ANES pilot survey, women who are white Trump voters are around 20 points less likely to say that they experience sexism than their Clinton-voting counterparts. However, white Trump voters are nearly 20 points more likely than white Clinton voters to say that they have experienced at least “a little” racial discrimination.[40]

Partisan Racial Misperception and Personal Experience of Racism

Previous research shows that partisans entertain wide misperceptions about the attitudes of the other party’s voters. Republicans overestimate Democrats’ hostility to the police, preference for open borders, and lack of patriotism by around 30 points. Democrats misperceive Republicans’ level of hostility to Muslims and immigration by a similar amount.[41] As with misperception about whether black men are more likely to be shot to death by police or killed in a traffic accident, reports of personal experiences of racism are heavily shaped by partisan perceptions of outgroup racial bias.

No wonder, therefore, that African-Americans who “strongly agree” that white Republicans are racist are far more likely to report personal discrimination than blacks who “strongly disagree” that white Republicans are racist. On all but one question, there is an attitude gap in reported personal experience of at least 20 points. On the question of whether “police have treated you unfairly for being black,” the difference between those who strongly agree and disagree that “white Republicans are racist” reaches 34 points (Figure 12).

It is, of course, possible that personal experiences of racism have shaped attitudes toward Republicans and shifted personal ideology and voting behavior. However, the fact that those who feel strongly that white Republicans are racist are considerably more likely to mistakenly believe that more young black men are shot to death by police than die in traffic accidents—and that answers to the personal experience questions reflect the same pattern—suggests that attitudinally motivated reasoning is the more plausible explanation.

These results of several surveys that I conducted, as well as evidence from other sources, indicate that personal and national perceptions of racism are interrelated. This could be because those who have personally experienced racism are more likely to see it as a national problem and identify as liberal, but it is more plausibly accounted for by black liberals being more likely to perceive personal encounters as racist—or to recall them as such—than conservative blacks do.

The partisan/ideological and attitudinal differences that exist in reported personal experiences of racism (Figures 11 and 12) are consistent with beliefs about how big the problem of racism is in the U.S. (Figures 6 and 8), the probability of agreeing that discrimination makes it harder for blacks to get ahead (Figure 7), and the misperception about lethal police shootings (Figures 9 and 10). To get a sense of how important ideology and partisanship are for variation in reported racism, we can compare their effect with that of race itself. This shows that ideological effects are not much smaller than the difference in reported racism between whites and blacks.

Does Critical Race Theory Disempower African-Americans?

The correlations between ideology and perceptions of racism, whether as a national sentiment or in terms of personal experience, raise two important questions: Might the emerging ideology of critical race theory (CRT) distort perceptions of racism among both blacks and whites? If so, what might this imply for the well-being of African-Americans?

Writers such as Christopher Rufo and Coleman Hughes have drawn attention to many unfalsifiable and damaging claims of CRT. Much of this discussion focuses on CRT’s generalizations about white people and the division that this seeds among the body politic.[42]

But there is another criticism: a possibly detrimental effect of CRT narratives on the black people whom it is ostensibly designed to help. John McWhorter regularly points out that the work of CRT authors such as Ibram X. Kendi, Ta-Nehisi Coates, and Robin DiAngelo tends to endow whites with the power to change themselves while portraying blacks as passive subjects whose fate is dependent on the goodwill of white people.[43]

In order to assess the possible impact of CRT on black empowerment, I had part of the survey sample in Prolific 1 and Prolific 3 first read a passage from Ta-Nehisi Coates’s “Letter to My Son”:[44]

Another group read no passage before answering, while a third group read a different passage that I composed:

I then asked respondents to indicate what their view was (strongly agree, agree, neither agree nor disagree, disagree, strongly disagree, don’t know) of the passage that they had read and to answer several questions on what psychologists refer to as the locus of control scale, which measures whether people feel able to control their lives or whether they think that their fate is determined by forces outside their control. Higher belief in one’s ability to control one’s fate is linked to positive mental health outcomes.

The measures were:

- When I make plans, I am almost certain that I can make them work.

- No matter how much I try, I don’t receive any credit for what I do.

- It is my responsibility to make the most of my talents and abilities.

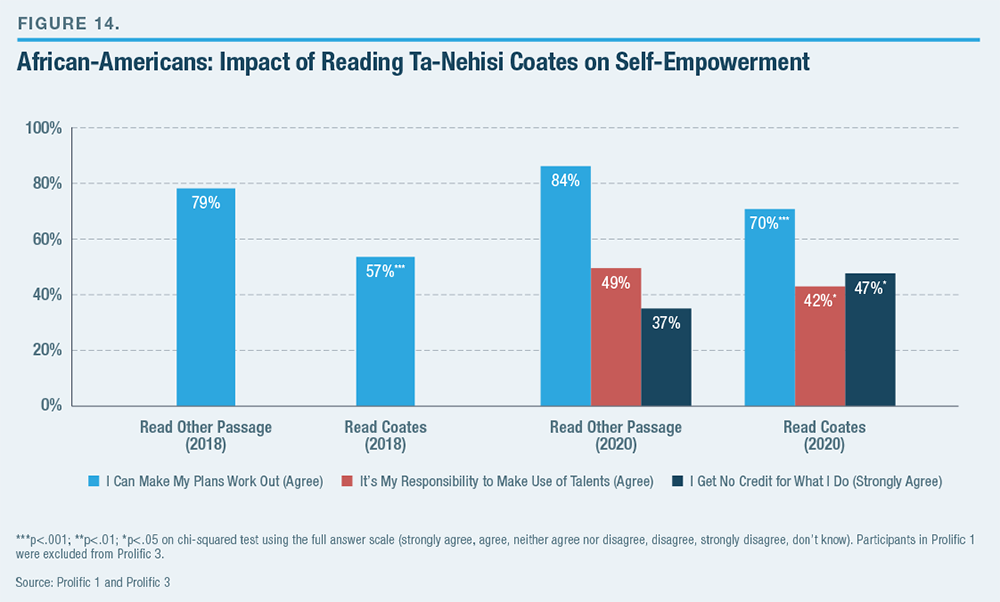

Combining the results in Prolific 1 and Prolific 3 on the first statement show that 83% of blacks who did not read the Coates passage said that they could make their life plans work out—while only 68% of those who read Coates said that they could do so (Figure 13). The impact of even one short passage of CRT was enough to reduce black respondents’ sense of control over their lives.[46]

Combining the results in Prolific 1 and Prolific 3 on the first statement show that 83% of blacks who did not read the Coates passage said that they could make their life plans work out—while only 68% of those who read Coates said that they could do so (Figure 13). The impact of even one short passage of CRT was enough to reduce black respondents’ sense of control over their lives.[46]

Prolific 3 measured responses to the second and third statements (Figure 14). It shows that reading the Coates passage had a significant disempowering effect on blacks on all three locus of control measures.[47]

Toward Black Resilience

For John McWhorter, critical race theory diminishes black people: “In supposing that Black people have no resilience, you are saying that Black people are unusually weak. You’re saying that we are lesser. You’re saying that we, because of the circumstances of American social history, cannot be treated as adults. And in the technical sense, that’s discriminatory.”[48]

Do African-Americans share McWhorter’s selfaffirming approach, or might they prefer the extra protection promised by CRT’s program of affirmative action, linguistic penalties, and reeducation? To explore this further, I first asked the survey samples in Qualtrics 2 whether they agreed or disagreed with the following: “Blacks will never be truly equal if society doesn’t hold them to the same standards as others.” Among the 801 black respondents, 68% agreed with this statement on a 7-point scale (strongly agree, agree, somewhat agree, neither degree nor disagree, somewhat disagree, disagree, strongly disagree), with only 14% disagreeing. Only a few points separated black liberals and black conservatives. There was a statistically significant difference by age, however, with 75% of blacks aged 18–30 agreeing with the statement, compared with 57% of those over age 60. Young African-Americans appear especially keen to be treated as equally competent and responsible citizens.

Microaggressions

Even so, perhaps black Americans want to be psychologically protected from whites via stronger regulation of speech. CRT emphasizes surveillance and compliance measures to shift white people toward what they deem to be appropriately inoffensive language. The contention is that the way language constructs meaning reinforces racial power structures while offending the sensibilities of minorities.[49] In order to probe this, I posed this question in Qualtrics 1 and Qualtrics 2:[50]

Though some people may find political correctness (PC) both demeaning and necessary, a forced-choice question compels respondents to weigh which aspect is more important to them. In Qualtrics 1 (Apr. 20–June 2, 2020), 56% of African-Americans and 57% of whites said that PC was demeaning to blacks, compared with 43% of whites and 44% of blacks who said that it was necessary to protect them. In Qualtrics 2 (Nov. 20–Dec. 1, 2020), blacks also indicated that PC was demeaning rather than necessary, but by a smaller (51%–49%) margin.

There was no significant average difference in opinion between blacks and whites on this question, even after controlling for age, sex, ideology, education, and marital status. Instead, ideology, not race, shaped opinion on political correctness—with ideological effects most pronounced among whites (Figure 15). Liberal-conservative ideology was significantly associated with answers to the PC question after controlling for age, gender, and education, though the strength of the association is greater among whites. Thus, white liberals and conservatives differed by nearly 20 points on the question while black liberals and conservatives disagreed by only 3 points.

There was no significant average difference in opinion between blacks and whites on this question, even after controlling for age, sex, ideology, education, and marital status. Instead, ideology, not race, shaped opinion on political correctness—with ideological effects most pronounced among whites (Figure 15). Liberal-conservative ideology was significantly associated with answers to the PC question after controlling for age, gender, and education, though the strength of the association is greater among whites. Thus, white liberals and conservatives differed by nearly 20 points on the question while black liberals and conservatives disagreed by only 3 points.

Columbia University sociologist Musa al-Gharbi, among others, has commented that most minorities are not offended by many of the “micro-aggressions” set out by University of California guidelines.[51] Responses from Qualtrics 2 largely comport with al-Gharbi’s comment. When asked, “What is your feeling when a white person says, ‘I don’t notice people’s race’?” 32% of blacks replied that they were “very offended” or “somewhat offended,” 22% said that they were “somewhat pleased” or “very pleased,” and 47% said that they were “neither pleased nor offended.”

However, when they were asked, “What is your feeling when a white person says, ‘America is a colorblind society’?” a slim majority of black respondents (51%– 49%) said that they would be at least somewhat offended. Ideology figured in their responses. There was a 13-point gap between black liberals and conservatives (38%–25%) on the offensiveness of “I don’t notice people’s race” and a 21-point gap (63%–42%) on “America is a colorblind society” (Figure 16). Here, education level was as strong a predictor as ideology as to whether a black person would be offended. University graduates were 12–19 points more likely to be offended than those without degrees, comparable with the 13–21- point gap between liberals and conservatives. University-educated liberals were 26–27 points more likely than conservatives without a degree to feel offended by these statements. In addition to ideology, attending college appears to have a distinct effect in sensitizing black respondents to microaggressions.

The ideological divide was, as expected, wider among whites. When Prolific 4 (Dec. 1, 2020) asked a sample of whites if they were offended “when a white person says, ‘I don’t notice people’s race’ and when a white person says, ‘America is a colorblind society,’ ” the difference between liberals (who were offended) and conservatives (who were not) was a very large 44 points on “I don’t notice people’s race” and 57 points on “America is a colorblind society.” These responses are about twice as high as the ideological split among African-Americans. Education made no significant difference in predicting white responses to the microaggression statements.

America, like other societies, may never be able to reduce the incidence of racist epithets to zero. Nonetheless, increasing the penalty for racially offensive language is likely to have at least some deterrent effect. Is it right to pursue this path even with diminishing returns? Perhaps, but an alternative avenue to explore is to emphasize African-Americans’ resilience to whatever racism still remains—as Jonathan Haidt contended, there is wisdom in the rhyme that “sticks and stones may break my bones but names will never hurt me.”[52] For Bradley Campbell and Jason Manning, this is the defining characteristic of the healthy dignity culture that replaced the older honor culture or today’s campus-led victimhood culture.[53]

When asked to choose between a highly punitive regime of antiracism and a world marked by minority resilience, it appears that a majority of African-Americans prefer a future marked by group resilience over one of external protection. Qualtrics 2 posed this question: “If you had to choose, which is your ideal society?”

- Minorities have grown so confident that racially offensive remarks no longer affect them.

- The price for being racist is so high that no one makes racially offensive remarks anymore.

While it is naturally the case that people may agree with both statements, the priority given to one over the other tells us something important. Overall, black respondents chose the first option (which I call resilience) over the second option (punitive antiracism) by a 53–47 margin. However, there is a 15-point difference between black conservatives and black liberals on this question: 62% of black conservatives, but just 47% of black liberals, chose resilience. There was no statistically significant difference on the ideal society question by age, gender, or education.

Figure 17 combines Qualtrics 2 (black-only respondents) with Prolific 2 and Prolific 4 (white-only respondents). Once again, ideological breakdowns show a larger difference among whites than blacks: 63% of white conservatives, but only 29% of white liberals, favored the resilience option. While 53% of black liberals favored the punitive option, 71% of white liberals backed it—a difference of nearly 20 points. Ideological differences on race are greater among the white population than among African-Americans. White liberals, it appears, are considerably more attached to a regime of punitive antiracism than African-Americans overall, a majority of whom prefer a future of minority resilience.

Figure 17 combines Qualtrics 2 (black-only respondents) with Prolific 2 and Prolific 4 (white-only respondents). Once again, ideological breakdowns show a larger difference among whites than blacks: 63% of white conservatives, but only 29% of white liberals, favored the resilience option. While 53% of black liberals favored the punitive option, 71% of white liberals backed it—a difference of nearly 20 points. Ideological differences on race are greater among the white population than among African-Americans. White liberals, it appears, are considerably more attached to a regime of punitive antiracism than African-Americans overall, a majority of whom prefer a future of minority resilience.

Coda: Sad and Anxious People Report More Racism

Throughout this report, I have emphasized two points: first, that racism has been amplified by ideological and media construction; and second, that it is partly in the eye of the beholder. While people’s general psychological dispositions are less susceptible to social construction than their ideological outlook, personal psychology is also strongly connected to reported experiences of racism and discrimination.

In order to tap respondents’ general level of depression and anxiety, I asked, “How often you would say that you feel sad or anxious?” in Qualtrics 1 and 2. Replies were provided on a scale from “never” through “always” sad or anxious. Those saying, “about half the time,” “most of the time,” or “always” made up 29% of the 1,028 white respondents and 26% of the 1,788 black respondents. These responses were then cross-tabulated with the agree/disagree responses to the statements “How often would you say that you experience racism in your daily life?” and “I have experienced a great deal of discrimination in my life.”

Unsurprisingly, Africans-Americans reported experiencing more racism and discrimination than whites. It should also be noted that men, whether white or black, report experiencing more racism and discrimination than women. But it is striking that, regardless of race or measure, those who report being sad or anxious at least half the time are far more likely to report experiencing racism and discrimination (Figure 18). Controlling for age, gender, and education, the association of psychological sadness and anxiety with reported racism and discrimination is highly significant and is similar for whites and blacks. As the dotted lines show, the two lines track each other, with the saddest and most anxious whites and blacks reporting 20 points more racism. In fact, psychology is only somewhat less powerful than race in predicting reported racism. While it is not impossible that whites and blacks who experience racism report more sadness, the more likely explanation is that certain psychological states are correlated with reporting more negative experiences.

Conclusion

This paper began by noting the Tocquevillean paradox that concern about racism has risen even as racist attitudes and behaviors have declined. Across a range of surveys and questions, I found that ideology—and, to a lesser degree, social media exposure and university education—has heightened people’s perceptions of racism. Depression and anxiety are linked to perceiving more racism. The level of racism in society reported by whites appears to be driven more by political leaning than the level reported by blacks. Nevertheless, ideology plays an important part among African-Americans in shaping national perceptions as well as reported personal experiences of racism.

Surveys showed that liberal whites are more supportive of punitive CRT postulates than blacks, who are more likely to aspire to agency and resilience. Moreover, CRT appeared to have a detrimental effect on African- Americans’ feeling of being in control of their lives. This makes CRT a poor choice for policymakers seeking to improve outcomes in the black community.

Finally, my survey results indicate that as much as half of reported racism may be ideologically or psychologically conditioned, and the rise in the proportion of Americans claiming racism to be an important problem is largely socially constructed.

None of this means that racism has been eradicated. Nevertheless, the policy approach that follows from the findings in this paper is unlike the narrative of “systemic” racism that is increasingly prevalent in professional settings. This approach would replace the narrative common among activists and diversity administrators in elite institutions, which is based on anecdote-driven reasoning, sweeping CRT narratives, and conclusions drawn from bivariate race “gaps.” In their stead would come measurable indicators and tests to explain disparate racial outcomes that control for confounding factors such as educational qualifications, and in which claims of racism achieve validity only when alternative explanations such as qualification level fail to explain differences. Racial disparities that stem from education and class can be addressed with less contentious, race-neutral economic initiatives.

Where racial bias continues to manifest itself, mentoring, nudges such as name-blind CVs, and the use of randomized control trials to ascertain which interventions work should be favored over shaming, virtue-signaling, and quotas. The realization that all groups discriminate against all groups can also help lower the divisiveness of a debate often cast in binary “majority-minority” terms. In Britain, a recent survey shows that nonwhites, who make up only 20% of the population, accounted for over 40% of reported ethnic and racial discrimination against black Britons.[54] Policymakers should avoid unnecessarily generalizing about, and impugning the reputation of, an entire racial group such as white Americans. Targeted, evidence-led, progress on correcting unexplained racial disparities—as with the rougher treatment of black suspects by police or lesser likelihood of prescribing black people pain relief—is vital, but policymakers should interpret subjective perceptions of racism with care.[55]

Endnotes

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).