The Fiscal Implausibility of Medicare for All Federal health spending under M4A would grow to exceed all current federal spending as a % of GDP.

Last week the Mercatus Center published my estimates of the cost of the Medicare for All (M4A) bill introduced in the US Senate by Senator Bernie Sanders (I-VT) along with 16 co-sponsors. Although my work on the study began several months ago, the moment of its publication was fortuitous, coinciding with the embrace of M4A by several political candidates across the country. As a result, the level of press attention and public commentary on the study has been overwhelming. AP provided the initial coverage on Monday, leading to several other good articles, such as this one in The Hill. On Wednesday I published a summary of the results in the Wall Street Journal. Countless pieces have been published about the study, including particularly insightful ones from Megan McArdle in the Washington Post and Chris Deaton at The Weekly Standard.

In this article I will summarize the key findings of the study, provide simplified explanations of the derivations, and finally touch on a few issues that have arisen since its publication.

The Aggregate Costs of Medicare for All

First, a brief description of M4A itself. Despite the name, the legislation would bring nearly all Americans into a national single-payer health insurance system that differs from Medicare in key ways. It would provide first-dollar coverage of a widened range of healthcare services (including, for example, dental, hearing and vision) while stipulating (with a few exceptions) that “no cost-sharing, including deductibles, coinsurance, copayments, or similar charges, be imposed on an individual.” Grossly simplifying, instead of Americans paying for their healthcare through a combination of private insurance, other government insurance programs, and out-of-pocket payments as we do now, we would instead send that money to Washington as tax or premium payments, and the federal government would pay for nearly all the health services we use, right from the very first dollar.

Unsurprisingly this proposition turns out to be very expensive, at least for federal taxpayers. The primary estimate presented in the study is $32.6 trillion over the plan’s first 10 years of full implementation (which, if enacted this year, would be 2022-31 due to the legislation’s phase-in period). Important context should be attached to that number. First, $32.6 trillion would not be the federal government’s total costs, but its new costs over and above what it already spends on healthcare programs and other subsidies. Total annual federal health spending under M4A would be $4.2 trillion in 2022 and rise to $6.9 trillion by 2031. Second, the cost estimate is based on the literal language of the bill without regard to whether its intended outcomes are probable, as this article will further explain. Actual federal cost increases under M4A are likely to be substantially higher than the estimated $32.6 trillion over its first ten years.

How best to understand the real-world magnitude of such an eye-popping number? The annual marginal cost of enacting M4A starts out at around 10.7% of GDP and rises to 12.7% of GDP within the first 10 years, continuing to grow beyond that. As the study explains, even a doubling of all projected individual and corporate income taxes would be insufficient to finance these added federal costs.

We have never undertaken a sudden, permanent expansion of government of this size. Total federal spending under M4A on healthcare alone would equal 17.9% of GDP in 2022 and rise to 20.8% of GDP by 2031. For context, consider that all US government spending this year totals 20.6% of GDP. And it bears repeating: even these numbers understate the likely cost of M4A.

Breaking Down the Cost Estimate

Estimating the price tag of M4A essentially involves estimating the costs for which the federal government would be responsible under the plan, and comparing those to current federal obligations. An important step is estimating healthcare utilization. There is an extensive economics literature demonstrating that the more medical care insurance finances, the more people consume. This is true separate and apart from the services’ value and efficacy: people consume more of both necessary and unnecessary services if insurance pays for them. M4A would therefore fuel a substantial increase in healthcare demand through its provision of first-dollar coverage of a widened range of services.

The utilization increase under M4A would of course be greatest among the currently uninsured, but it would also be substantial for other populations, including current Medicare participants who lack supplemental coverage, and current holders of private insurance whose consumption is presently constrained, at least somewhat, by the requirements of deductibles and copayments.

As we as a nation grapple with how to contain rising healthcare costs, it’s important to understand the extent to which insurance itself drives costs upward. The increased demand that would arise under M4A’s expanded coverage is substantial – adding an estimated $5.7 trillion to projected national health spending during 2022-31 all other things being equal, an increase of more than 11%. That number is probably understated for reasons that go beyond the scope of this article.

Against that topline cost increase, M4A contains provisions designed to bring costs down. Its language directs the HHS Secretary, for example, to “promote the use of generic medications to the greatest extent possible.” Interpreting the “greatest extent possible” very literally as achieving 100% penetration of generics in prescription drugs, one arrives at an estimate of $0.8 trillion saved during 2022-31 in lower drug prices. This estimate does not account for other possible, less desirable effects such as lessened pharmaceutical innovation, nor does it allow for less-than-perfect success in replacing brand-name drugs with generics. Accordingly, it should be thought of as an upper-bound estimate of the savings possible from the bill’s drug provisions.

The estimates also assume M4A would have lower administrative costs than private health insurance. I used fairly aggressive assumptions of seven percentage points for the administrative costs saved by bringing those now covered by private insurance under M4A. My study as well as a previous Urban Institute analysis explains why this is likely the upper limit of potential administrative cost savings under the plan. The savings projected under this assumption are roughly $1.6 trillion over 2022-31.

Now we come to an important comparison. While it is sometimes said that M4A’s elimination of private-sector profit and overhead would bring national health costs down, that is not what the numbers indicate; more specifically, to the extent lower administrative expenses do reduce total costs, these would be more than offset by the higher service demand under M4A. Even under the fairly aggressive cost-saving assumptions outlined above, the potential savings from lower administrative costs and lower drug prices combined are less than half the additional costs expected to arise from expanding the scope of insurance.

This is where the factor of provider payment rates comes in. The text of the M4A bill specifies that healthcare providers will be paid at Medicare payment rates, which are roughly 40% lower than the rates paid by private insurance. Previous studies published by the Urban Institute as well as Emory professor Kenneth Thorpe (prior to the bill’s introduction) assumed this would not be possible, because such dramatically reduced payment rates would be well below providers’ reported costs of delivering services. My study took first a literal interpretation of the bill’s text: that these dramatic provider cuts would be implemented immediately.

It need hardly be said that cutting provider payment rates by roughly 40% for those now working through private insurance -- down to below their reported costs of providing services -- while at the same time increasing service demand by 11%, would have potentially dire and unforeseeable effects on the availability, timeliness, and quality of healthcare. Understand, these are not gradual cuts in the manner of the Affordable Care Act, but rather immediate cuts upon implementation of M4A. We simply do not know what would happen if the literal text of the M4A bill were carried out. But obviously, if we assume provider payments are suddenly cut by 40%, national health expenditures would naturally fall relative to current projections.

In recognition of the unlikelihood of such dramatic provider cuts being implemented as written, the study contains an alternate scenario in which payments to providers remain unchanged as a national average. Under that scenario, national health expenditures under M4A would rise even faster than under current law, and the price tag for federal taxpayers would rise to $38 trillion.

Some have suggested that the study provides evidence for the view that replacing for-profit private health insurance with administratively efficient single-payer insurance will enable more people to receive better benefits for less money. That is incorrect or, at best, an incomplete interpretation. Per above, my study found instead that the potential administrative efficiencies of M4A could only save much less than the induced additional service utilization would cost. It is not the single-payer system itself, but rather cutting payments to hospitals, doctors and nurses that would produce a scenario showing lower national health spending. Without those payment cuts, projections for M4A show not only dramatically higher federal costs but higher national costs as well. Moreover, even with such payment cuts assumed, we still couldn’t say that Americans would get better benefits for less money under M4A, because we simply do not know how many providers would continue to provide services once their income is cut so sharply.

Returning to the derivations, the net federal cost is determined by comparing federal costs under M4A to those the federal government would carry under current law. This calculation requires adjustments reflecting M4A’s stipulations that the federal government wouldn’t pay for absolutely all national health spending. (As one example, the M4A bill requires that states continue to fund current long-term supports and services (LTSS) through Medicaid, and also allows out-of-pocket payments for LTSS to continue.) The resulting federal costs under M4A are compared with current federal healthcare subsidies, including not only direct spending on programs like Medicare and Medicaid but also subsidies delivered through the tax code, such as the tax preference for employer-sponsored insurance.

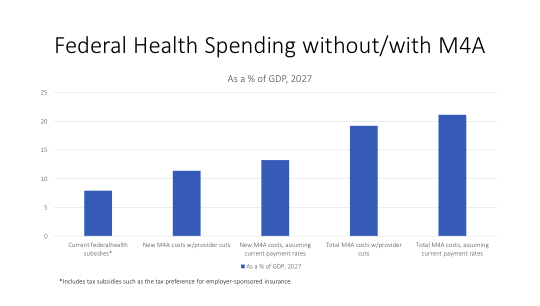

The following graph attempts to simplify and contextualize the results, using the year 2027 as an example. The graph shows the net additional costs of M4A, as well as the total federal costs of M4A, both with and without the assumption of roughly 40% provider payment cuts.

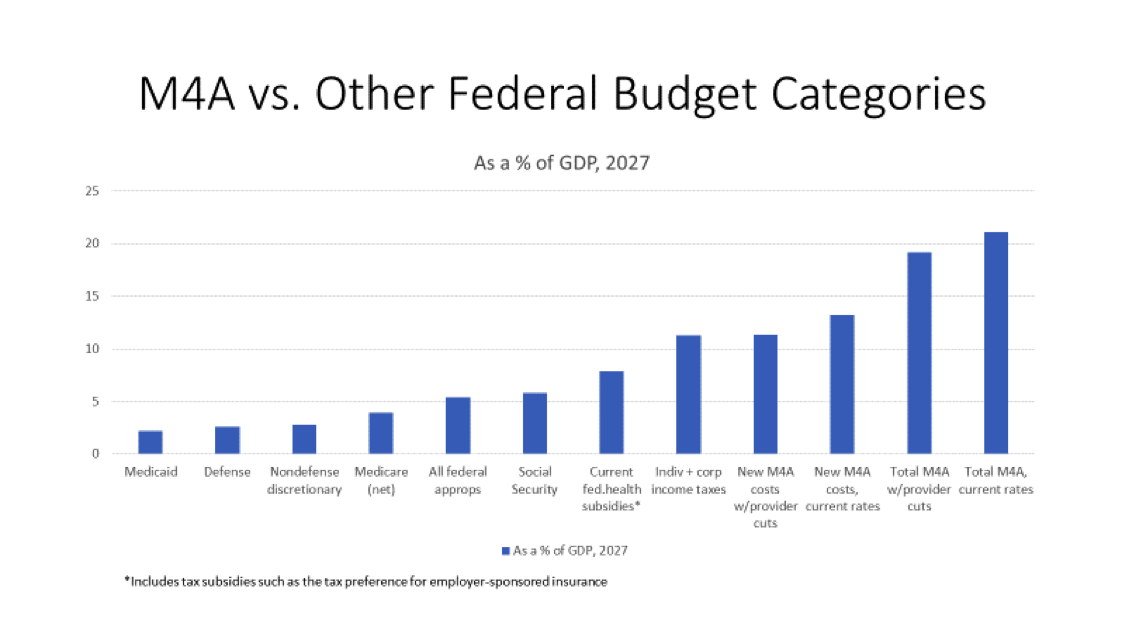

As can be readily seen from the preceding graph, enacting M4A would be an unprecedented expansion of federal spending. The following graph compares both the additional and total federal costs of M4A with those projected for various other categories of the federal budget. There are several striking comparisons in this graph, but a few stand out: even assuming the dramatic provider payment cuts, net new costs under M4A would exceed all projected (individual and corporate) federal income taxes, as well as being more than four times as large as the entire defense budget.

How Should People React to These Findings?

These numbers are intended to provide information that members of the public can use to inform their thinking about M4A. How people receive the numbers is up to them. My own reactions to these findings needn’t determine the reactions of others.

Information about M4A’s costs is nevertheless important to have, irrespective of whether one supports or opposes M4A. Those who are concerned about federal finances and skeptical of M4A should know the extent to which their concerns are well-founded. M4A proponents, too, should know the costs of making their vision a reality, and understand the questions it raises about whether financing M4A is feasible. Perhaps even more importantly, undecided citizens should have an opportunity to understand the cost implications before becoming invested in one position or the other.

If healthcare utilization rises under M4A, it means more people are getting care that they need. That’s good. But the other side of the coin is more health spending, as well as additional utilization of less-effective and less-necessary services, creating more competition among patients for access to care -- especially if the supply of healthcare providers proves inadequate to meet increased demand.

M4A’s effect on federal finances, and its effect on national health expenditures, are both important considerations. Some commentators have implied that the potential benefit of a (slight) reduction in national health expenditures (even if driven exclusively by provider payment cuts) is all that really matters, irrespective of the strain on federal finances. Most readers will understand why that interpretation is impracticably narrow. After all, the federal government must be able to finance its operations. If it cannot handle the extra burden of financing $33 trillion to $38 trillion in spending over 10 years, it doesn’t really matter whether that federal spending would have brought about a 4% acceleration or a 4% deceleration in national health spending. What matters first is whether the federal government can even do it.

A primary effect of M4A would be to replace private spending on healthcare with government spending financed by federal taxpayers. Americans would pay for no deductibles or cost-sharing, but they would pay much higher taxes. This change dwarfs any projected changes in national health spending, which in turn are a highly contingent, unpredictable function of whether and how deeply provider payments are cut. The observation that Americans are already paying for most of these expenses, while technically true, by itself glosses over the important question of whether they are willing to have their taxes raised sufficiently to have the government pay for them.

An analogy might help frame the choice. Suppose, for example, that a government representative came to your door and said, “We’ve totaled up all the money you spend each year on food. We think you’re wasting money paying for restaurants’, groceries’, and farms’ costs of doing business, as well as others in the food industry. We think we can do this more efficiently. So we’re going to raise your taxes by that amount of money, and we’ll provide all your food to you for free. And we’ll also be able to take care of those Americans who don’t have enough access to food. We’re planning to cut all payments to restaurants, groceries, farms and other food providers by about 40%, and if we do that we might be able to cut 3-4% off of your total food bill.” Would Americans take this deal?

Maybe some would. But it’s nearly certain many would not. First, it’s a huge amount of money to turn over to the government. Even if shown how much they were already spending, it doesn’t necessarily follow that Americans would want to pay that much in additional taxes. The potential for a 3-4% reduction in their food costs might not make up for surrendering all control over how they spend on food. Second, they would be correct not to trust the government to follow through with those 40% payment cuts, once lobbyists for the food industry enter the picture – and if the government doesn’t do so, then their food costs would rise at the same time that they lose a great deal of control. Third, if the payment cuts do go through, Americans might worry that their favorite restaurant would close and that they’ll not be able to eat there anymore. They might also worry about the lines that would form at grocery stores and restaurants as 40% cuts send many of those establishments out of business. Finally, some may simply not want to give up their remaining power to choose how much to spend on food, no matter how the numbers shake out.

An important thing for Americans to know is that financing M4A would require more funds than doubling all projected individual and corporate federal income taxes would generate, and indeed that the actual financing required would likely be significantly greater even than that, depending on how deeply the government is willing to cut payments to doctors, nurses, hospitals and other healthcare providers. On the other side of the coin, Americans would be excused from paying for healthcare in the many ways they currently do. As the idea of M4A is discussed, financing the unprecedented federal cost should be considered whenever and wherever there is a discussion of its potential benefits.

Charles Blahous is the J. Fish and Lillian F. Smith Chair and Senior Research Strategist at the Mercatus Center, a visiting fellow with the Hoover Institution, and a contributor to E21. He recently served as a public trustee for Social Security and Medicare.

Interested in real economic insights? Want to stay ahead of the competition? Each weekday morning, e21 delivers a short email that includes e21 exclusive commentaries and the latest market news and updates from Washington. Sign up for the e21 Morning eBrief.