Taxing More Earnings Won’t Fix Social Security’s Finances

A few years ago, I explained why the frequently-floated idea of increasing the amount of worker earnings subject to the Social Security tax would not fix much of the program’s large and growing financing shortfall. It seems worthwhile to update this information in the context of the evolving political climate surrounding Social Security, for two reasons. One reason is that the idea continues to turn up in more places, including Congressional proposals, opinion columns and options lists compiled by government scorekeepers. The second reason is that Social Security’s financial situation has deteriorated further since the original piece, so a tax cap increase today would solve even less of the problem than it would have back then.

The purpose here is not to oppose legislated adjustments to Social Security’s maximum taxable annual earnings. To the contrary, I recently served on a Bipartisan Policy Center commission that included a tax cap increase in a package of retirement security recommendations I believe are worthy of lawmakers’ strong consideration. Moreover, political realities are such that virtually any bipartisan grand bargain to repair Social Security finances is likely to include such a provision. The purpose of this piece is instead narrowly informational: to explain why increasing (even eliminating) the cap wouldn’t accomplish nearly as much financial improvement as many people believe.

Background: The 12.4% Social Security payroll tax is assessed on worker earnings up to an annual limit currently set at $127,200. The cap is statutorily indexed to grow (with rare exceptions) with growth in the national Average Wage Index (AWI). A worker’s eventual benefits are based in large part on his/her career earnings subject to payroll taxation.

The reason the cap exists is rooted in Social Security’s historical design as a contributory insurance program rather than a welfare program. President Franklin D. Roosevelt and other program founders wanted to ensure that Social Security covered and would have wide support from Americans rich and poor. As a result, workers at all income levels pay into Social Security, and workers at all income levels earn benefits as they do so. Past a certain point, higher-income people don’t need extra benefits, so both their contributions and benefits stop.

Financial effects of raising the cap: Absent fundamental changes to Social Security’s design, raising the cap on taxable wages would bring in more revenue up front but trigger additional outlays later on. This is because to a first approximation, the more you pay in, the greater the benefits you earn. Raising the cap both delays and modestly reduces Social Security’s financing shortfalls, with the modest improvements coming primarily because less generous benefit returns are provided for tax contributions at the upper-income end. There is also a sense in which part of the apparent financial improvement is illusory – i.e., an artifact of actuarial calculations that capture several cohorts’ increased tax obligations but not their additional benefit accruals.

Overall, a tax cap increase is a very inefficient way to improve system finances because it increases both tax collections and benefit expenditures for those who need them least. (A further factor is also relevant, that higher-income people’s longevity improvements are outpacing those of poorer people; if that trend continues, raising the tax cap -- and thereby paying more benefits throughout higher-income people’s longer lives -- would be even less efficient in improving program finances.)

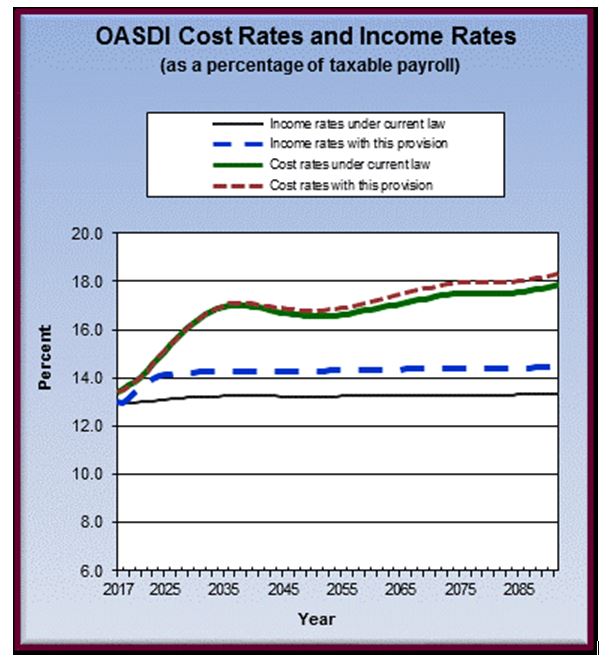

Graphs published by the office of the Social Security Chief Actuary illustrate the inefficiency of a tax cap increase. The first graph here shows the projected effects of an often-floated proposal to raise the cap to cover 90% of all national wages. CBO has estimated this would require raising the cap to roughly $245,000.

As the picture shows, raising the cap would cause tax collections to increase almost immediately (from the solid black line to the dashed blue line) but would also cause expenditures to grow (from the green line to the dashed red line), reducing net annual shortfalls over the long run by only 14%.

Even total elimination of the cap and exposing all US salary income to taxation (right on up to every last such dollar paid to Bill Gates) wouldn’t fix most of the shortfall. In the out years, the annual gap between income and outgo would be reduced by roughly 36%, leaving nearly two-thirds of the long-run financing problem in place.

The Hobson’s Choice: Because of the situation illustrated above, proposals to raise the cap on taxable wages confront policy makers with a Hobson’s choice between two alternatives:

1) Credit the additional contributions towards benefits, consistent with Social Security’s historical design; or

2) Don’t credit the additional contributions towards benefits, thereby abandoning Social Security’s historical design.

Both choices are highly problematic. As noted above, choice #1 is very inefficient from a financing perspective, paying additional benefits to people who generally don’t need them. Most experts would say #2 is even worse, because it would be a radical change to Social Security policy that leaves every participant’s benefits less secure.

If and once the link between contributions and benefits were broken, this step almost certainly couldn’t be undone. Moreover there is no reason to believe, once contributions above a certain income threshold are no longer counted toward benefits, that the specific dollar-amount cutoff will be set in stone forever. Ongoing financing pressures would virtually guarantee that the cutoff is frequently and perpetually adjusted downward, so that all of us would be at permanent risk of being forced to pay taxes into the program without receiving anything for those contributions.

There is a potential way out of this dilemma. An increase in the cap on taxable wages could be coupled with reductions in benefit accrual rates for higher-earners. That way, less of the additional revenues collected would be sent inefficiently back out the door in the form of higher benefits. This would not fundamentally change Social Security’s design because higher-earners already receive a lower return rate than lower earners: it would just be a matter of changing the number in the formula. A number of bipartisan proposals containing changes to the earnings cap have included variations on this approach, including the BPC retirement security commission as well as the Simpson-Bowles commission. On the other hand, one needn’t raise the tax cap to slow the growth of higher-income participants’ benefits in this way, improving finances and increasing program progressivity at the same time.

In any event, a tax cap increase by itself does very little to fix Social Security’s financing problem. The pitfalls of the approach do not end there, also including likely adverse effects on personal savings and economic growth, as well as the unwanted distributional outcome of hitting the upper middle class harder than the so-called “1%.” Still, the idea will undoubtedly remain part of the Social Security discussions because of the attractiveness to some of further taxing the rich. It just wouldn’t do much to mitigate the other tough choices required to balance Social Security finances.

Charles Blahous, a contributor to E21, holds the J. Fish and Lillian F. Smith Chair at the Mercatus Center and is a visiting fellow at the Hoover Institution. He recently served as a public trustee for Social Security and Medicare.

Interested in real economic insights? Want to stay ahead of the competition? Each weekday morning, E21 delivers a short email that includes E21 exclusive commentaries and the latest market news and updates from Washington. Sign up for the E21 Morning Ebrief.

iStock Photo