Reassessing “Carter-Case” Spending for Students with Disabilities in New York City Schools

Executive Summary

New York City’s special-education system looks very different today from the way it did a decade ago. For the 2026 fiscal year, 2.15% of the Department of Education’s entire budget was approved for “Carter-case” tuition reimbursement. Originally meant as a safeguard for students denied a Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE),[1] the Carter framework has expanded far beyond its intended purpose. Policy decisions such as the shift to settling previously won cases and reducing annual FAPE adjudications have allowed private placements to continue year after year without determining whether the district can meet students’ needs in NYC. As filings increased, the city’s spending on tuition reimbursement also increased significantly, even as outcomes for many private programs remain unknown.

NYC’s experience serves as a warning for states and large districts nationwide. With shifting more authority to states, NYC shows how deviations from the annual accountability structure of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) can reshape incentives, obscure program quality, and create inequities in access to services. Reassessing Carter cases in NYC is essential to restore IDEA’s accountability structure, rebuild the nation’s largest public school system’s capacity, and ensure that students receive appropriate services in their least restrictive environment (LRE),[2] without relying on litigation.

Overview of Individuals with Disabilities Education Act

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) is federal legislation that guarantees students with a disability a special education and other related services. Initially enacted in 1975 as the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (EHA), it was designed to ensure that children with disabilities received an adequate public education and had legally enforceable protections.[3] Congress reauthorized and renamed it IDEA in 1990, and again in 2004.[4] In 1990, the law established disability categories and a framework for parents’ rights. In 2004, Congress aligned special education with No Child Left Behind (NCLB) by adding an accountability system and procedural reforms.[5]

Under IDEA, every student with a disability is guaranteed the right to Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE) through an Individualized Education Program (IEP).[6] School districts are required to write their own IEPs, but those plans must implement the services that IDEA mandates, and the IEP for each individual child must be reviewed annually. When an IEP is not fully implemented, the school district is denying a child FAPE. IDEA established a due-process system that allows parents to challenge a district’s failure to provide FAPE,[7] and, furthermore, the school district must revisit the question of whether it can adequately provide FAPE at least once a school year.[8]

Under IDEA, FAPE consists of special education and related services provided at public expense, under public supervision, in correspondence with the student’s IEP and in accordance with state standards.[9] The least restrictive environment (LRE) is also an essential component of FAPE.[10] Under IDEA, districts must educate students with disabilities in the LRE appropriate to their needs. This means that children with disabilities should be served alongside students without disabilities whenever possible. LRE is part of the district’s core FAPE obligation and is supposed to be evaluated each year through the IEP process.

Origin of Carter Cases

Families of children with IEPs and special needs send their students to private schools, when the local public schools fail in their duty to provide FAPE. “Carter cases” are legal proceedings in which families seek reimbursement from the state for private school tuition.

The framework for tuition reimbursement in special education began with the Supreme Court’s 1985 decision in School Committee of Burlington v. Department of Education.[11] This case addressed what should happen when parents believe that a public school’s proposed IEP[12] does not meet their child’s needs and choose to place the child in a private school at their own expense. Before this case, IDEA did not explicitly state whether reimbursement was available.[13] The court held that parents may unilaterally place their child in a private school if the public school fails to provide FAPE. Qualified parents take on the initial financial risk, but may seek reimbursement.

Burlington led to conflicting rulings across the country, with some federal courts holding that parents could not receive reimbursement if the private school was not state-approved.[14] In the Second Circuit (the federal appellate court with jurisdiction over New York, Connecticut, and Vermont),[15] courts denied reimbursement on that basis—most notably, in Tucker v. Bay Shore Union Free School District.[16] The court held that reimbursement was not available unless the state approved the parent-selected private school.[17]

In 1993, the Supreme Court resolved the state-approval split in Florence County School District Four v. Carter. The Court held that when a district denies FAPE, courts may order tuition reimbursement for an otherwise-appropriate private placement, even if the private school is not state-approved.[18] This is the origin of Carter cases. Under the Carter framework, courts apply a three-part review to determine whether parents may receive tuition reimbursement. Parents may receive reimbursement if the district failed to offer FAPE, the parent’s unilateral placement is appropriate, and equitable considerations support reimbursement.[19]

There are also enforcement mechanisms. When the city DOE fails to evaluate or place a child within legally required timelines, families may obtain immediate “Nickerson letter” placements in approved private schools, with automatic pendency (“stay-put”) rights.[20] This means that if DOE misses a deadline, families can move their child to a private school, and DOE would cover costs.

Today, Carter cases are a routine pathway for families in NYC to secure private school placements when they believe that DOE has failed to provide a FAPE.[21] During the Bloomberg administration, DOE hired additional lawyers and routinely contested parents’ reimbursement claims to limit private school placements and reduce special-education costs.[22] This changed under Mayor de Blasio, who directed DOE to stop challenging previously won cases and to settle a larger share of claims.[23]

IDEA requires districts to determine each year whether they can meet a child’s needs;[24] but in practice, many Carter placements continue for years with little to no reconsideration. Since DOE often settles renewal claims rather than defends the adequacy of its public school program, private placements can become effectively automatic once a family prevails in due process.

Special Education in NYC

NYC operates the largest special-education system in the United States. In the 2024–25 school year, approximately 228,000 students in NYC public schools were classified as having a disability, representing approximately 24% of the NYC DOE’s K–12 enrollment.[25] In addition to these district school students, the city’s special-education system includes District 75, which serves students with the most significant disabilities. District 75 enrolled 27,658 students in the 2024–25 school year and is reported separately because of its specialized instructional programs and settings.[26]

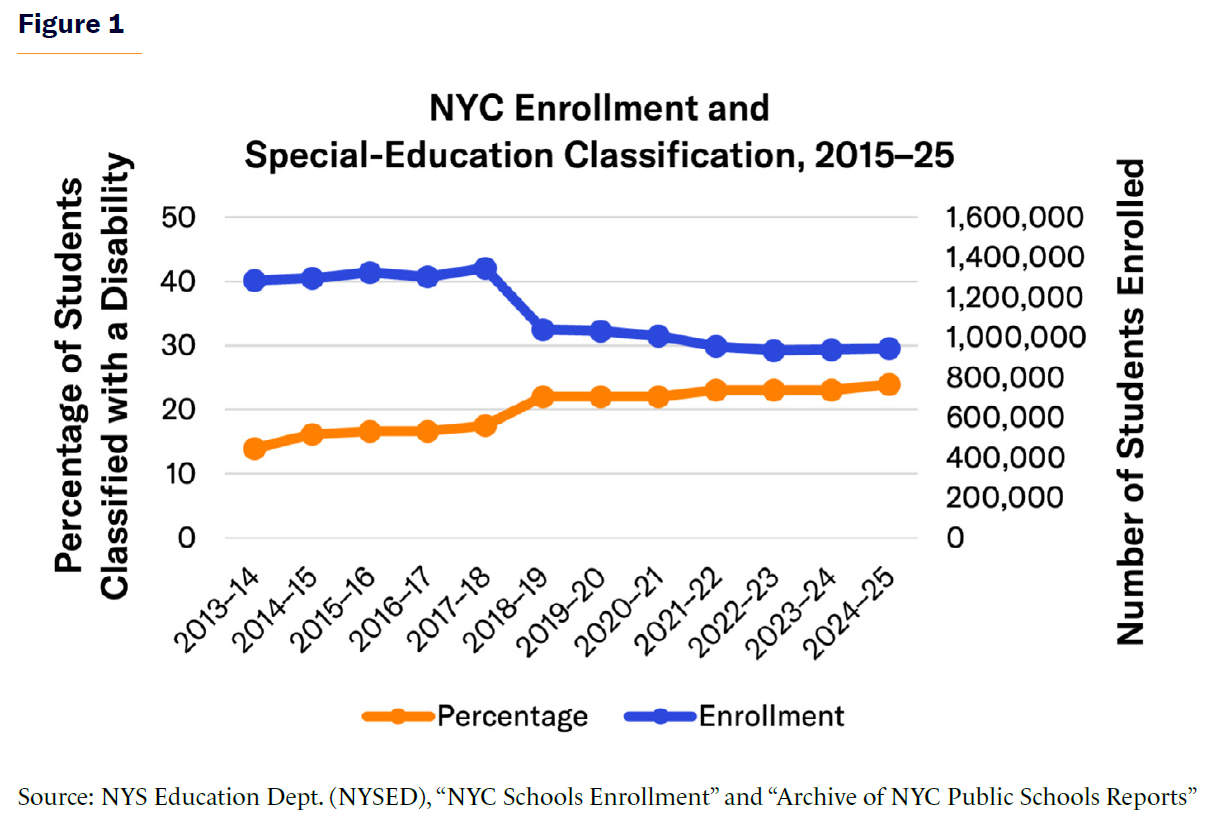

As shown in Figure 1, overall NYC K–12 enrollment declined from 1.3 million to approximately 946,747 between 2015 and 2025, and the proportion of students classified with disabilities increased from 17.5% to 24%.[27]

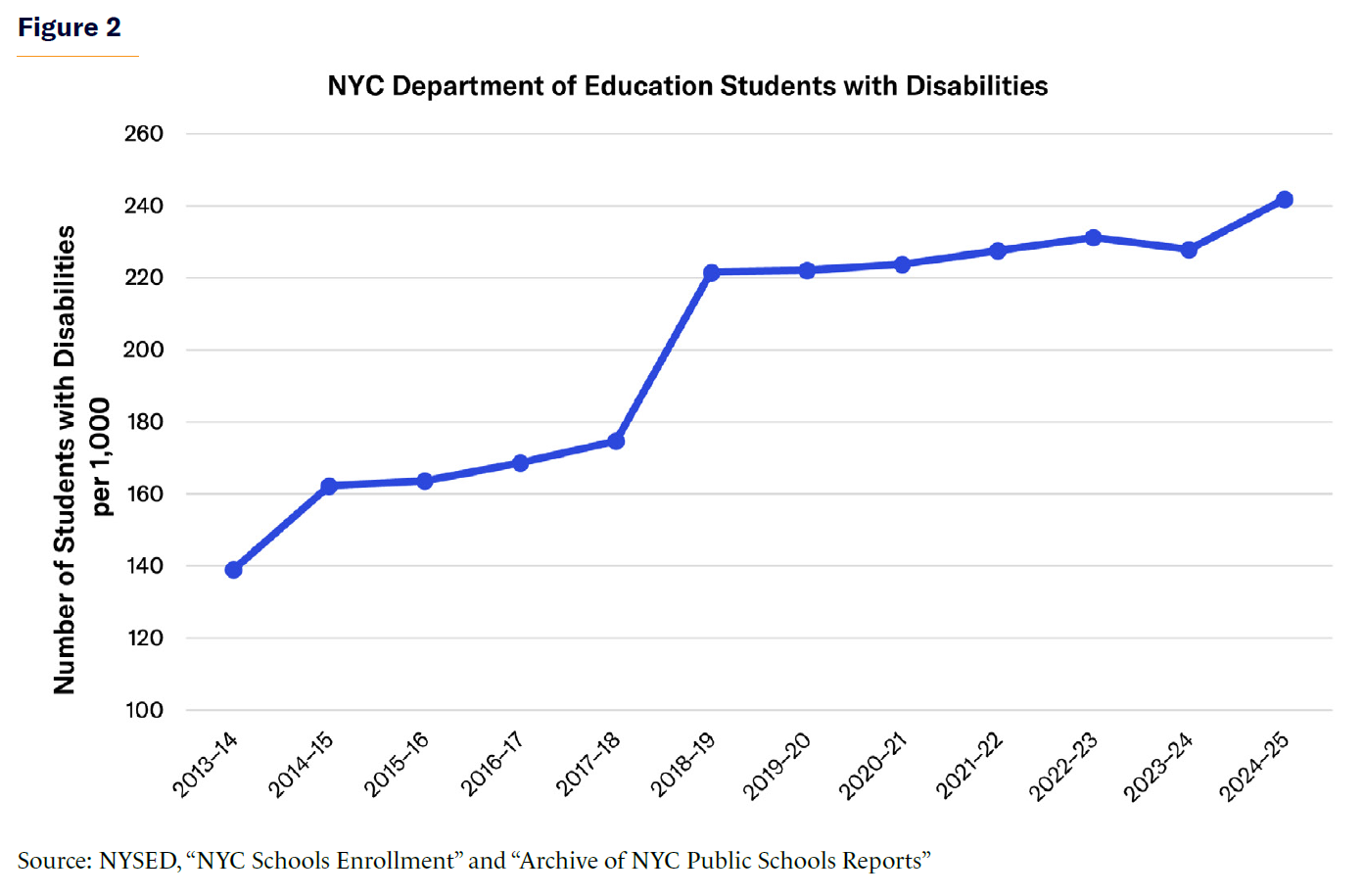

Between the 2013–14 and 2024–25 school years, the city’s rate of disabled students increased from 139 per 1,000 students to 242 per 1,000 students, a 74% increase (Figure 2). At the same time, enrollment decreased by approximately 340,000 students, moving these children either out of the city or into private instruction. In the latter case, parents seek reimbursement for their private school tuition through Carter cases.

FAPE Violations

NYC has shown long-standing difficulty in providing mandated IEP services, particularly for students who require speech therapy, occupational therapy, counseling, or specialized class placements.

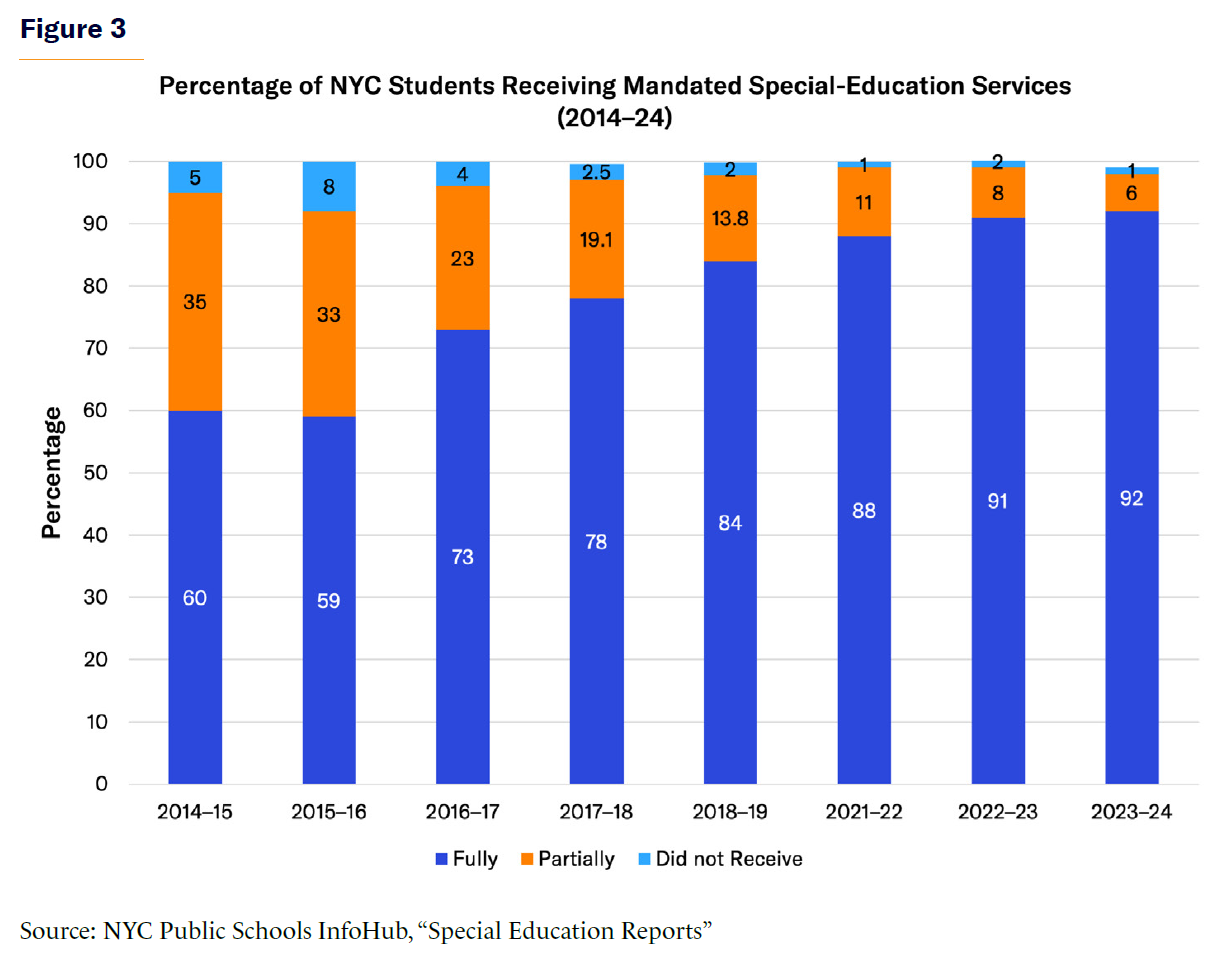

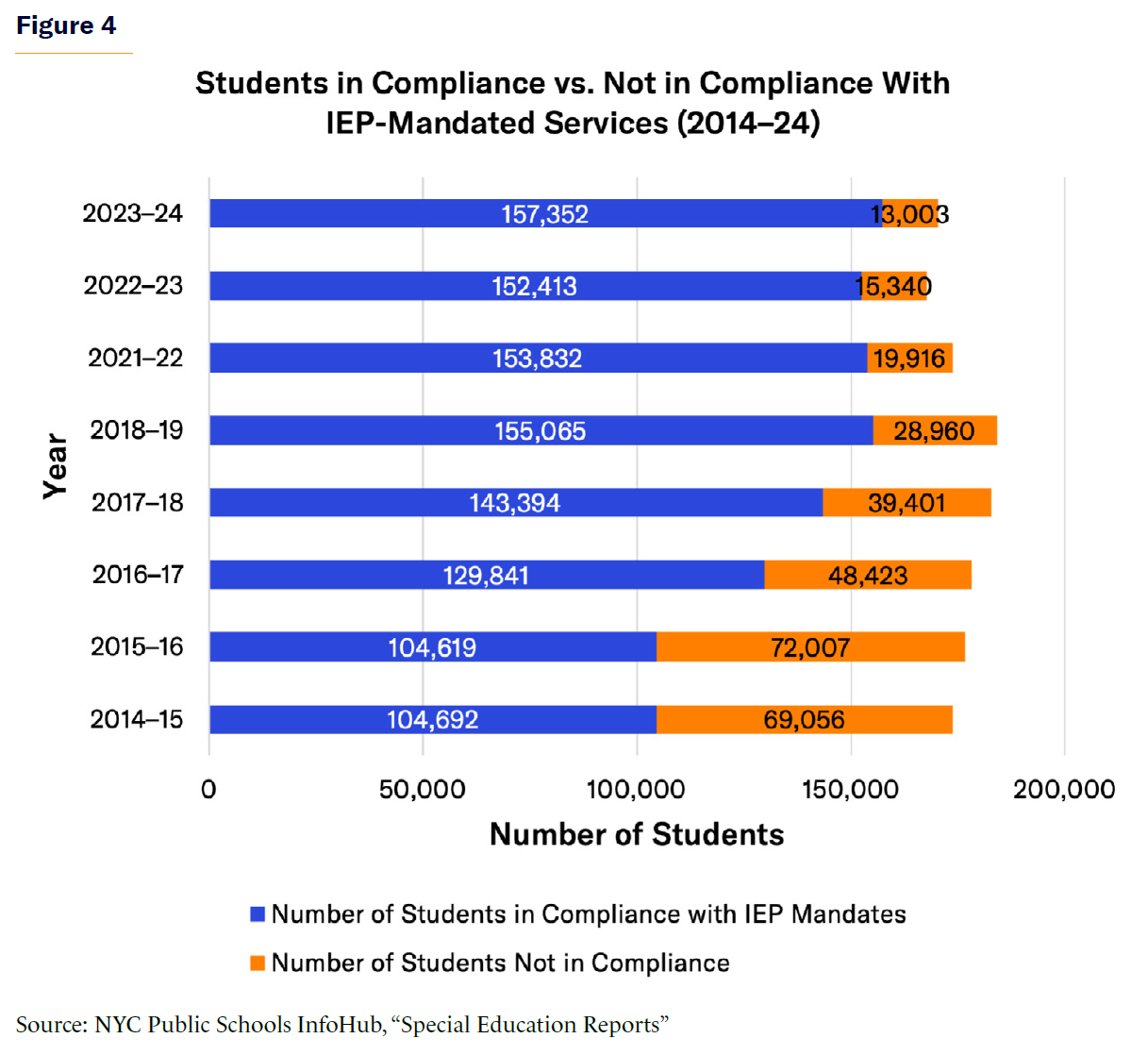

Figure 3 shows the percentage of students fully, partially, or not at all receiving mandated special-education services. Figure 4 shows the absolute number of students who are in compliance or not in compliance with those mandated services.

In 2014–15, the first year with publicly reported data, only 60% of students with disabilities received the services mandated in their IEPs.[28] The remaining 40% (69,046 students) received only partial services or no services at all. Compliance began to increase during the 2016–17 school year, when 73% of students fully received their mandated special-education services, while 27% (48,423 students) received some or no services. During the 2018–19 school year, fully mandated services were implemented for 84.3% of students, and 15.8% (25,960 students) received incomplete or no mandated services. During the 2022–23 school year, compliance exceeded 90% for the first time, 91% of students received fully mandated special-education services, and 10% (15,340) received partial or no services. The most recent public data for the 2023–24 school year showed that 92% of students received mandated special-education services, and 7% received partial or no services, totaling 13,003 students.[29] The 2023–24 school year coincided with a mandate issued by a NYC federal judge requiring 40 steps to eliminate delays in the provision of special-education services.[30]

Under IDEA, failure to implement an IEP is itself a denial of FAPE. Families then turn to private providers and private schools to secure the services that DOE is unable to deliver. Even as the total number of non-served students declined, the system has never reached full implementation, leaving thousands of families with annual legal grounds for reimbursement.

A Comparative View of IDEA: New York State and New York City

As mentioned earlier, beginning in 2014, NYC reversed its prior approach of contesting most private school tuition reimbursement claims each year. Under Mayor de Blasio, DOE adopted a policy of not re-litigating cases that parents had already won in previous years, settling a large share of claims, and expediting tuition payments.[31] This approach created a reimbursement process that diverged from IDEA’s expectation that school districts evaluate FAPE annually.

Table 1 [32]

| System Component | IDEA (Federal) | New York State | New York City |

| Role of Reimbursement | IDEA says reimbursement is a year-specific solution available only when the district fails to provide FAPE for that year. | NYS treats reimbursement as a year-by-year decision, requiring a new FAPE determination each school year and placing the proof burden on the district annually. | NYC continues funding many unilateral placements through pendency or settlement, resulting in fewer opportunities for annual adjudication of whether the district’s updated program meets FAPE. |

| Annual District Obligation to Present a Program | IDEA requires districts to revise and present a new IEP each year, demonstrating an appropriate public program for that school year. | NYS requires districts to prove FAPE annually at hearing, making each year an independent determination. | NYC’s practice of not presenting or defending updated IEPs disrupts the annual review structure built in to IDEA and NYS law, preventing the system from generating evidence of program quality or improvement. |

| Systematic Outcomes | IDEA establishes an annual review process that evaluates each new IEP and determines whether the district’s program meets federal standards for that school year. | NYS maintains this structure by requiring a new hearing record each year and a separate determination of whether the district met its FAPE obligation. | In many NYC cases, updated IEPs are not litigated because disputes resolve through pendency or settlement, limiting the number of hearings that evaluate whether the district’s new program satisfies FAPE requirements for that year. |

By choosing not to contest previously won cases year after year, DOE allowed many private placements to continue indefinitely, even when the district could have offered an appropriate public school program. In practice, a child who received tuition reimbursement in kindergarten could remain in a private school through elementary or middle school without renewed litigation, even if the district later developed an appropriate placement or the student’s needs changed.

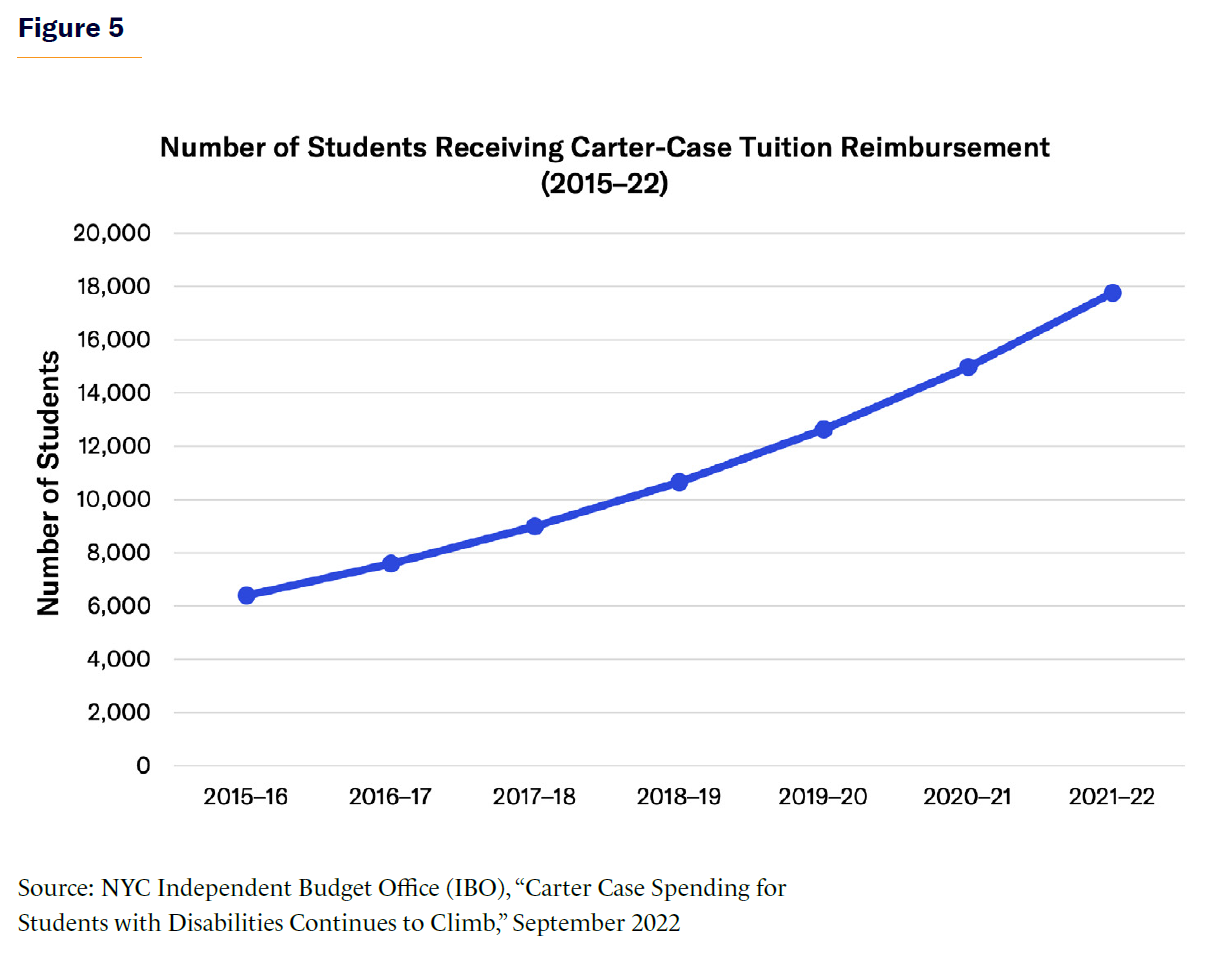

This is not consistent with IDEA’s annual evaluation structure, which requires ongoing evaluation of a child’s needs and the district’s program. The reduced annual adjudication of FAPE disputes meant that many placements were never reconsidered, reducing the system’s ability to determine whether students continued to require a private school setting, or whether the DOE could meet the students’ needs in a public-school setting. Following the 2014 policy change, the number of students receiving tuition reimbursement increased from 6,403 students in 2015–16 to 17,759 students in 2021–22.[33] Figure 5 shows this growth over time.

The 2014 tuition-reimbursement policy shift occurred at the same time NYC launched Pre-K for All, the citywide universal preschool initiative.[34] Beginning in the 2014–15 school year, NYC expanded free, full-day preschool for four-year-olds, increasing enrollment from 20,000 seats before the expansion to more than 70,000 seats within two years.[35] In 2017, this initiative was expanded to 3-K for All, with more than 39,000 students enrolled in the 2022–23 school year.[36]

Under New York law, preschool special-education services for children aged three to five are provided by approved programs, including district-run classes, Boards of Cooperative Educational Services (BOCES) programs (shared regional public educational programs that offer specialized services to public schools),[37] and nonpublic providers.[38] In NYC, DOE operates some preschool classes in district schools and pre-K centers but relies heavily on nonpublic providers for more specialized preschool programs.[39] When Pre-K for All and 3-K for All were launched, the number of preschool-age students evaluated also increased, but the preschool evaluation structure under the Committee of Preschool Special Education (CPSE) stayed the same. As a result, many preschool-age children with disabilities in NYC begin their education in small, specialized private settings before transitioning to kindergarten.[40] In other parts of the state, districts operate their own preschool special-education classrooms, so a larger share of services are district-run, rather than almost entirely through nonpublic providers.

Therefore, in NYC, tens of thousands of children with delays were now being screened, identified, and placed earlier into specialized private preschool settings. When these children transitioned from CPSE to the Committee on Special Education (CSE) at age five, families often compared DOE’s proposed kindergarten placements, typically larger and less specialized, with the small private preschool classrooms where their children had been progressing. Parents were dissatisfied. For many families, CSE’s recommended public school placement appeared to represent a loss of support, even though it met IDEA standards. This shift influenced how families approached Kindergarten placements.

During the same years that Carter-case spending initially surged, DOE expanded its central administrative staffing rather than its special-education capacity. In 2017, the number of administrators doubled under Mayor de Blasio and spending on central staff increased by about 70%, compared with 2013.[41] DOE did not make a comparable investment in in-house evaluators or DOE-run special-education programs, continuing instead to rely heavily on private evaluators and nonpublic preschool providers.[42] The result is a system with growing bureaucracy but limited internal capacity to deliver or defend public school placements.

State Comparisons of Due Process

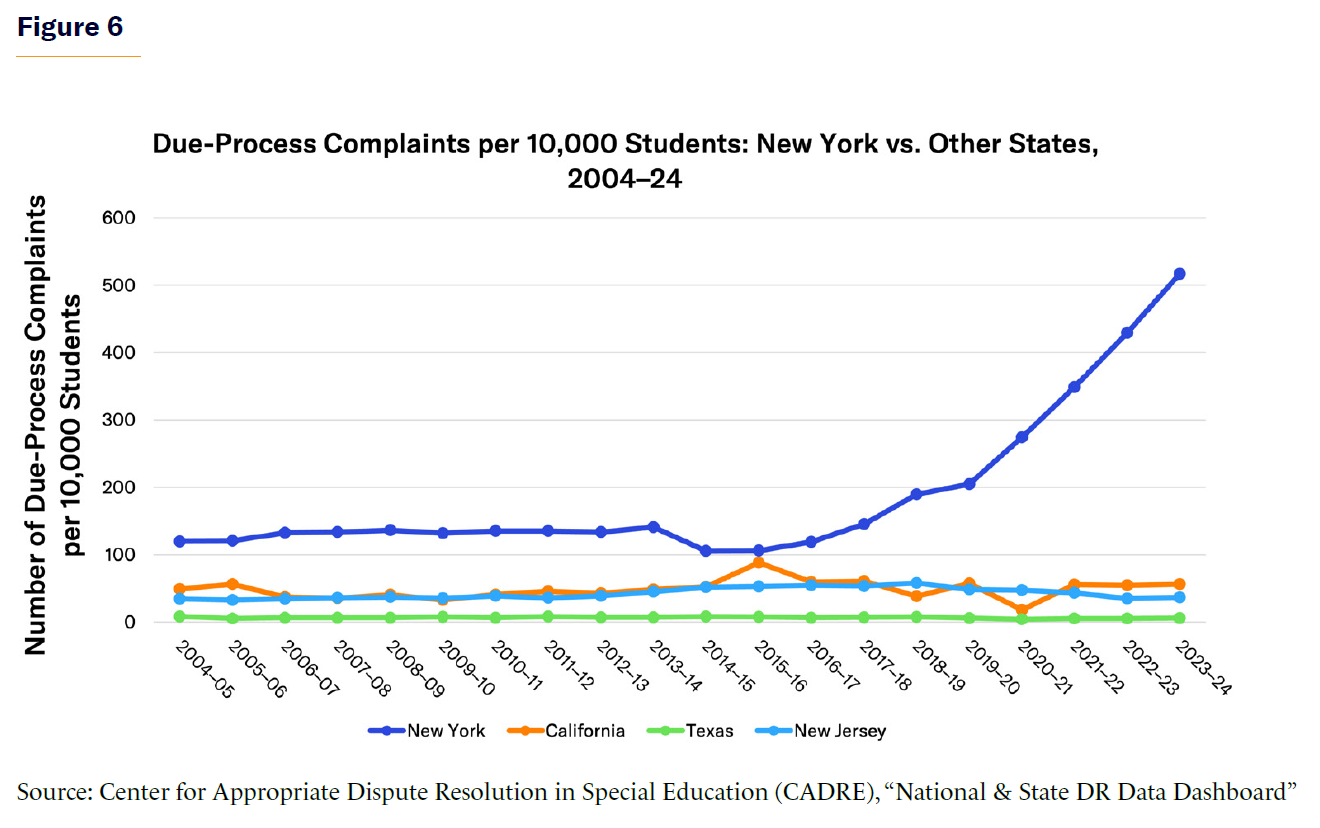

New York is a national outlier in the volume of special-education due-process complaints filed each year. Over the last two decades, New York has consistently received more filings per 10,000 students than any other large state. In 2004–05, New York reported 119.9 filings per 10,000 students, compared with 48.9 in California, 8.3 in Texas, and 34.5 in New Jersey. By 2018–19, the rate had increased to 189.8 filings per 10,000 students; by 2023–24, it had further risen to 517.1 in New York.[43]

No other state in the country, including California (the nation’s largest by population) or Texas (second-largest by population), shows anything close to this pattern. In 2018–19, California recorded 38.4 filings per 10,000 students and Texas 7.6. New Jersey, the neighboring state with the next-highest filing rate, reported 57.8 in 2018–19 and 36.9 in 2023–24 (Figure 6). In 2022, NYC was confirmed to account for the majority of these state filings (98% in 2020–21).[44] This volume has significant fiscal implications. Each complaint, especially those involving private school placements, can obligate the city to cover tuition, transportation, related services, and even attorney fees for each eligible student.

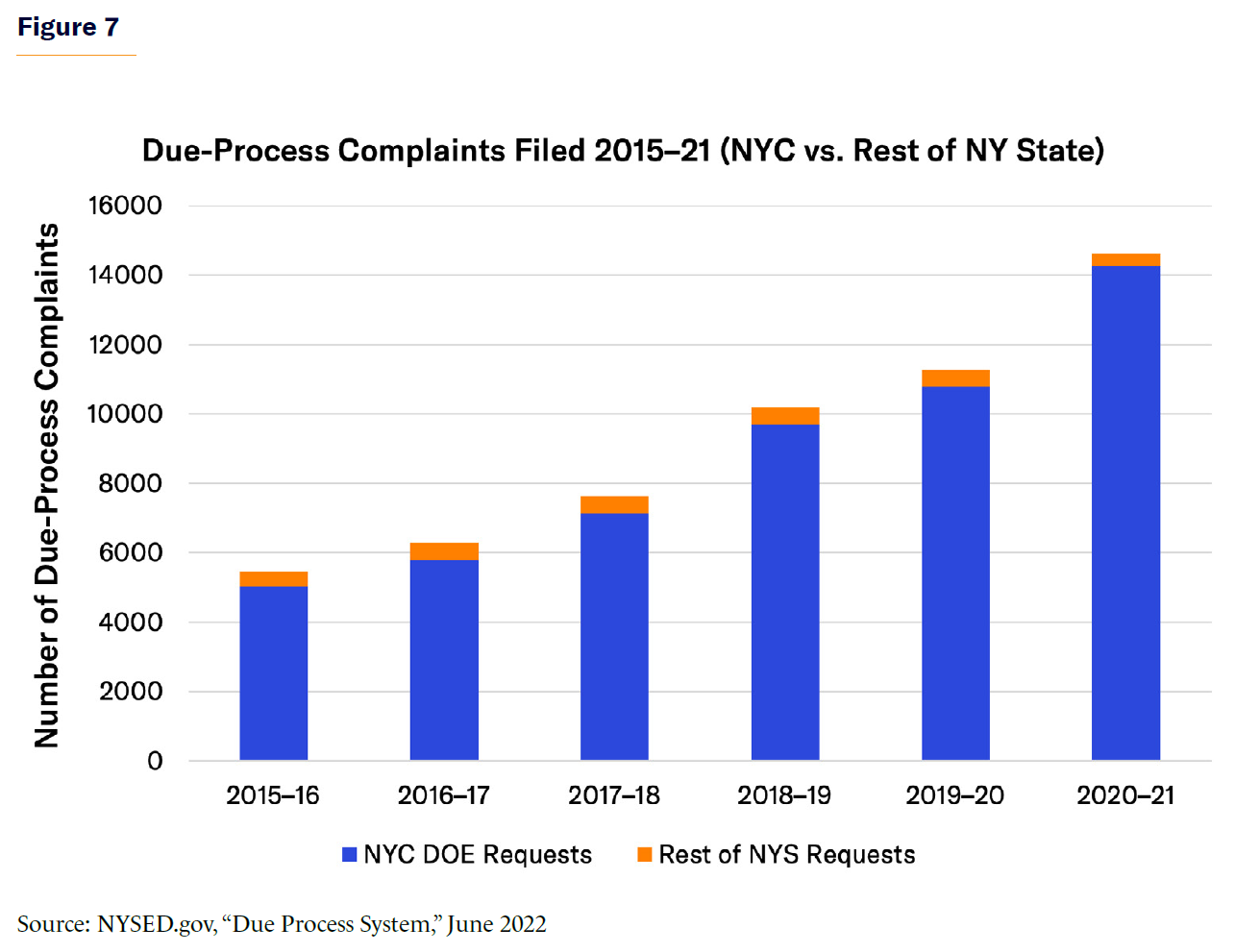

Between 2015–16 and 2020–21, NYC’s due-process filings nearly tripled, from 5,026 to 14,264, representing 92%–98% of all hearings statewide each year (Figure 7).[45] Over the same period, filings in the rest of the state decreased from 438 to 358. The large increase in due-process filings coincided with the de Blasio administration’s policy of settling most tuition reimbursement cases. These changes made a way for families to secure and maintain private placements and created a large backlog of unresolved cases, leading Mayor de Blasio, in the final days of his administration, to approve a major structural change: the transfer of all NYC special-education due-process hearings from the New York State Education Department (NYSED) to the Office of Administrative Trials and Hearings (OATH).[46]

In early 2022, according to OATH,[47] the number of cases awaiting assignment to an impartial hearing officer had reached approximately 11,000, and cases took an average of 282 days to resolve under the prior system. In response, the State Education Department transferred all NYC special-education hearings to OATH, which hired full-time hearing officers and created a dedicated Special Education Hearings Division. OATH reports that, following this transition, the assignment backlog was eliminated, and the average case was resolved in 119 days during the 2022–23 school year. Most recently, the average time from filing to case resolution in 2025 was 152 days (about five months).[48]

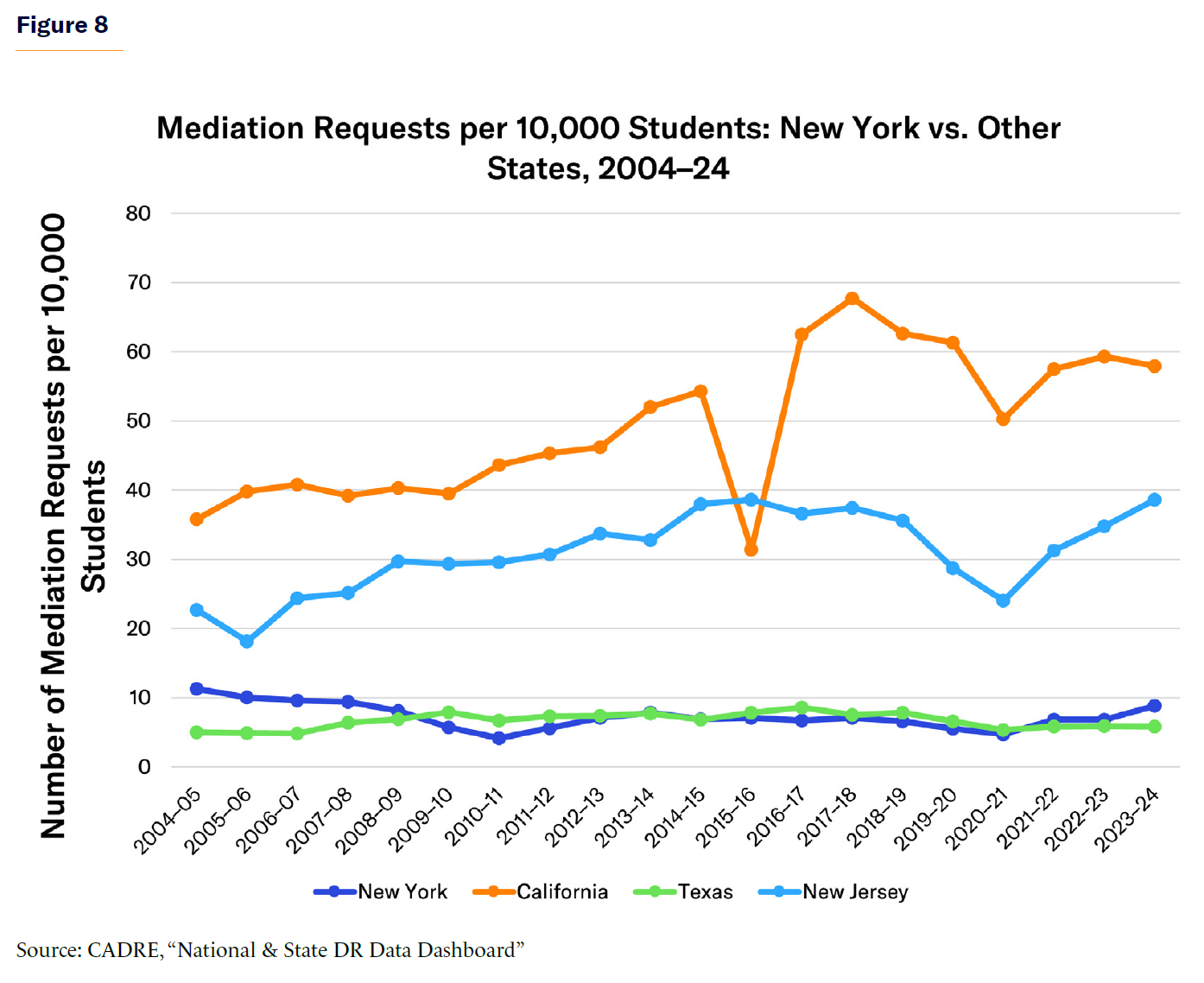

An alternative to going right to due process is “mediation requests.”[49] Mediation is an alternative, cost-effective way for school districts and families to work together to solve special-education placement or service concerns. New York State has one of the lowest rates of mediation requests (Figure 8).

Carter-Case Expenditures

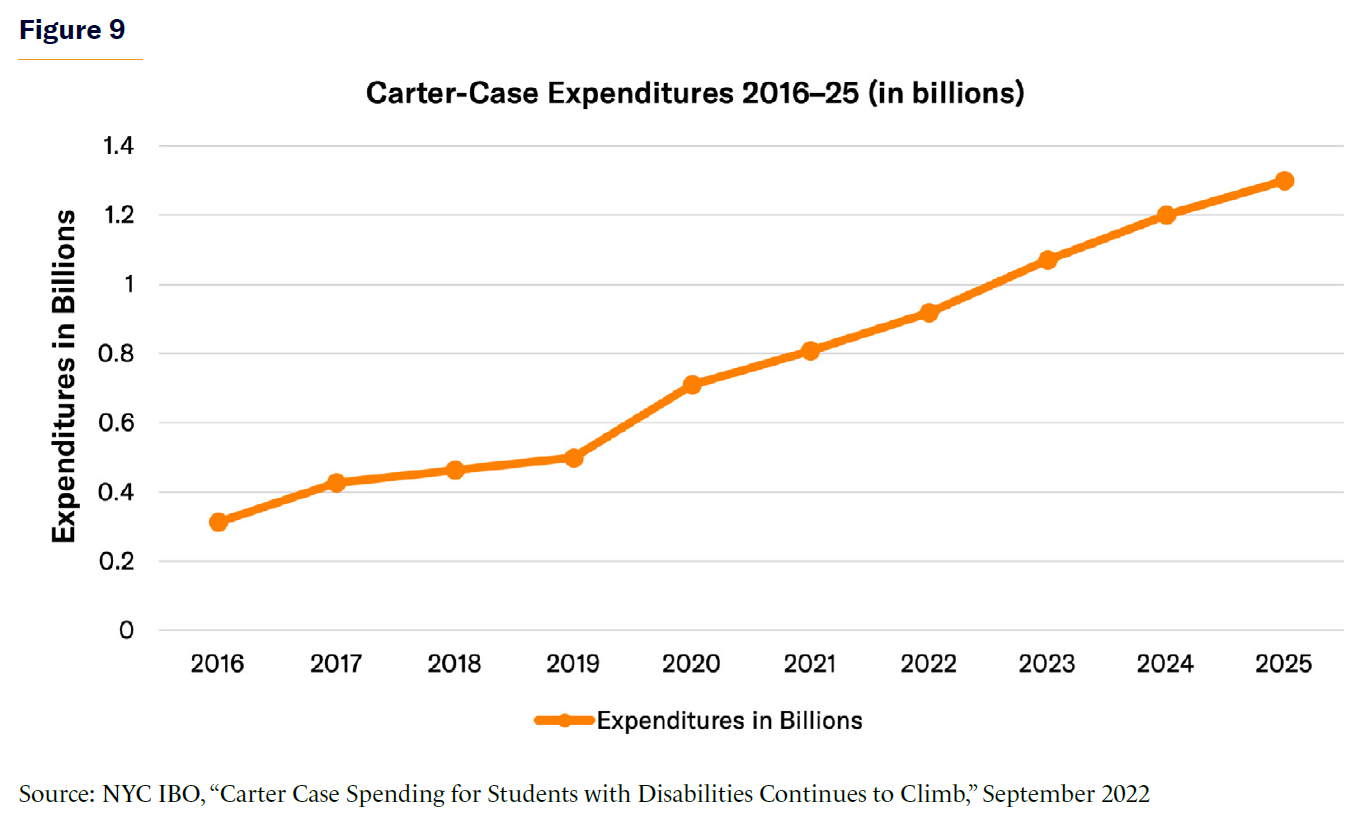

Carter-case expenditures have increased significantly over the past two decades. In 2005, NYC spent $47 million on Carter cases.[50] In 2010, that amount increased to about $143 million. NYC saw an increase of $312 million in the fiscal year 2016 to $1.3 billion in 2025. Beginning in 2020, spending increased from $499 million to $710 million in a single year. Increases have continued each year since: $807 million in 2021, $918 million in 2022, and $1.07 billion in 2023. By 2024–25, the city had spent $1.3 billion on Carter cases (Figure 9). This is equivalent to 3.25% of NYC DOE’s overall budget.

Equity and Access in Special-Education Services in NYC

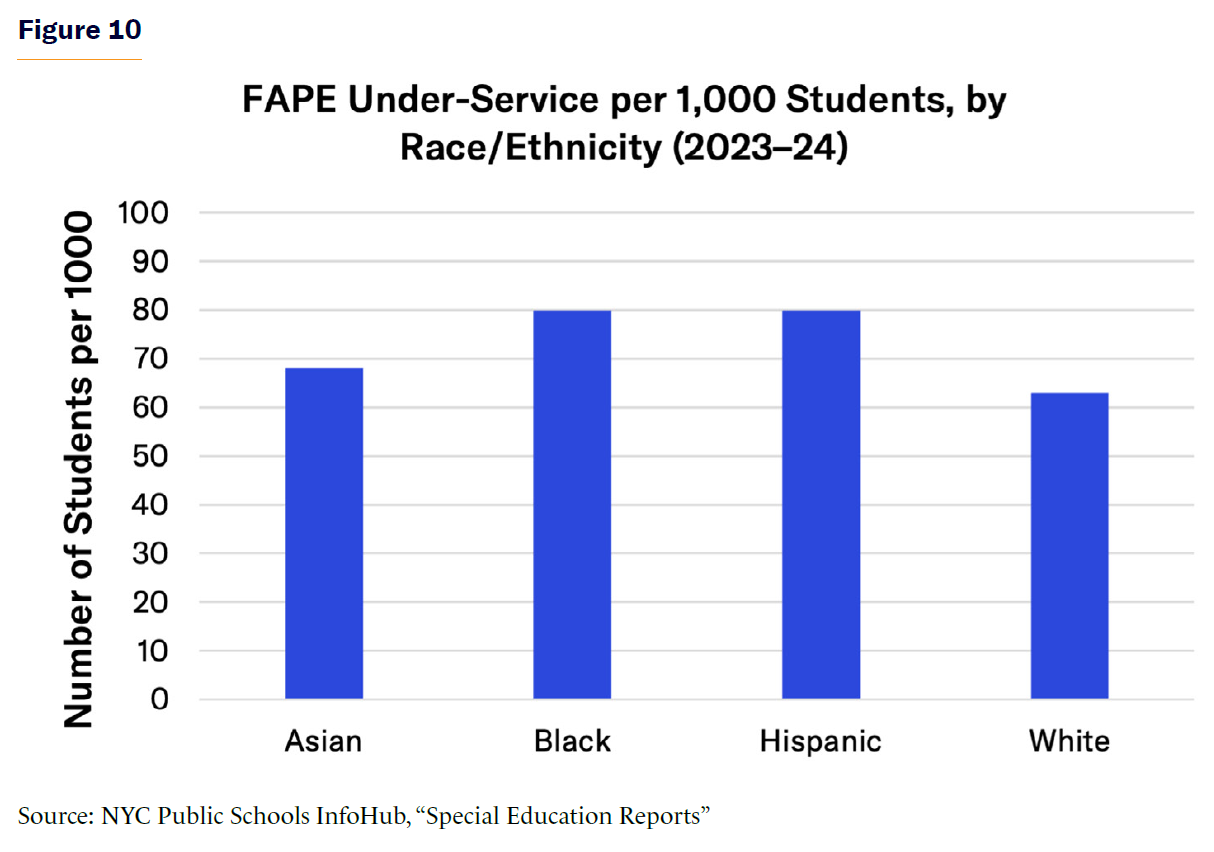

The implementation of special-education services has improved over time, but large gaps still remain. According to DOE, in 2023–24 many students continued to receive only some or no mandated services, both of which constitute noncompliance under IDEA. That academic year, about 80 of every 1,000 black and Hispanic students with disabilities received only some or none of their IEP-mandated services. By comparison, about 63 out of every 1,000 white students and 68 out of every 1,000 Asian students did not receive full services, as per their IEP (Figure 10).

These disparities can also be seen at the first stage of the special-education process: initial referrals. Even after accounting for overall enrollment, black and Hispanic students are consistently referred for special-education evaluation at rates higher than their share of the student population. In comparison, white and Asian students are referred at lower rates.[51] Although referral patterns do not determine service outcomes, they show that inequities in access appear to begin long before students receive mandated services. The same groups who experience delays at the referral stage are the ones most likely to be underserved after classification.

Carter cases were not evenly distributed across NYC’s five boroughs. In 2021, Manhattan accounted for the largest share of Carter cases, followed by Brooklyn, with substantially lower rates in Queens, the Bronx, and Staten Island. Within Manhattan, the Upper West Side recorded approximately 14.8 Carter cases per 1,000 students, while midtown and lower Manhattan recorded 8.2 cases per 1,000 students. Parts of Brooklyn experienced similarly elevated rates, reaching 6.7 cases per 1,000 students. By contrast, Queens averaged fewer than 1 case per 1,000 students, and Staten Island had the lowest rate citywide, at approximately 0.6 cases per 1,000 students.[52]

These patterns of inefficiency and inequity fall into the city’s incoming administration to address. Mayor Zohran Mamdani has talked about cutting waste and redirecting funds into classrooms.[53] And he listed special-education costs and due process as a contributing factor in the city’s deficit.[54] The current special-education system, which he recently inherited, in which families with more time, money, or legal support are better positioned to secure private placements, reflects inefficiencies that he can fix. Strengthening DOE’s capacity would create a more equitable structure, a theme that Mamdani has emphasized across his broader policy priorities.

Implications

In fiscal year 2025, NYC DOE’s total budget was $40 billion, and the city spent $1.3 billion on Carter cases alone (busting the original budget of $664 million).[55] For fiscal year 2026, DOE budget increased to $42.6 billion, with $935 million allocated for Carter cases, already 2.15% of the entire education budget, and still below the $1.3 billion spent the previous year.[56] As of May 2025, the average settlement per student was $101,757, more than three times the city’s $32,284 per-pupil spending.[57]

Many special-education disputes in NYC are resolved through settlement or pendency, rather than a full hearing. That means private placements continue year after year without a new determination of whether DOE can meet the child’s needs and without testing IDEA’s annual review structure.[58] Children have a legal right to a free and appropriate public education. But NYC DOE must have the chance to improve its programs and provide that appropriate education. Without consistent adjudication, the city pays the cost of placement when the question of whether a child could be appropriately served in a public program is unanswered.[59]

The evaluation structure adds another layer of complexity within NYC DOE. A significant number of preschool and school-age evaluations in NYC are completed by private contractors rather than by DOE school-based teams. School-based teams evaluate students within the public school system and must determine whether a child’s needs can be met through programs and services available in district schools under IDEA. Private evaluators, by contrast, assess children independently of the public school system and may recommend services, staffing ratios, or instructional models that reflect clinical best practice or the evaluator’s training but are not required to consider the specific programs, capacity, or constraints of the public school setting. These two roles serve different purposes and operate in different informational contexts, which means that families often enter the process with recommendations that may not align with what DOE can provide. When evaluations are primarily external to DOE, the department has fewer opportunities to demonstrate what its own programs offer, and disputes are more likely to escalate into requests for private placement.

Charter schools could play a larger role in expanding public capacity. While most charter schools in NYC do not offer highly specialized programs that families are looking for through Carter cases and charters can’t serve as pendency placements, some opportunities should be considered. If the city and state encouraged specialized charter programs and if DOE demonstrated that it can provide FAPE in comparable public settings, some families might choose charter programs rather than pursue private placements through litigation. Expanding specialized public options, including charter schools, could reduce pressure on the Carter system while increasing school choice for families. Currently, 19.3% of students enrolled in charter schools have IEPs,[60] showing that charters already serve a portion of students with disabilities and could build further capacity with city and state support.

Another challenge is that the Carter-case process is not equally accessible to all families. Many private schools require families to cover tuition up-front or take on financial risk while a case is pending. The result is a system in which access to a legally available placement can depend as much on a family’s financial capacity and ability to secure representation as on the child’s educational needs.

A final structural problem is that NYC’s dispute-resolution system creates conditions that make private placements the easiest option. Pendency guarantees uninterrupted payment once a family prevails. Many evaluations come from outside providers whose recommendations do not have to reflect the programs available in public schools. Since disputes in NYC rarely undergo annual adjudication, cases can be renewed with limited annual analysis, making it easier to keep a child in a private placement than to transition back to a DOE program. This helps drive the continued growth in Carter-case spending.

The long-term outcomes of students placed in private schools through the Carter process are unknown and often anecdotal. Unlike public schools, these private special-education schools are not required to report student progress, graduation rates, attendance, or postsecondary outcomes. NYC DOE cannot, therefore, evaluate program quality or effectiveness. Without outcome data, it cannot be determined whether these settings improve educational trajectories or substitute one inequity for another.

Recommendations

The current system in NYC is financially unsustainable and misaligned with IDEA. As of the 2024–25 school year, NYC public schools educate roughly one-third of all New York State students receiving special-education services.[61] Increasing NYC’s capacity to identify, serve, and support students with disabilities within public programs is one of the most essential actions that New York State can take. The following recommendations outline ways the state and city can restore IDEA’s intended structure and ensure that all students, not only those with legal or financial resources, receive high-quality public education.

Recommendation 1: Return to Year-by-Year FAPE Determinations

NYC should follow the letter of the law and return to annual adjudication of private placements. IDEA requires a new FAPE determination every school year. Reinstating the expectation that DOE must present and defend its updated IEP annually would restore the evaluative structure lost. This does not eliminate reimbursement, but it ensures that private placement continues only when the district cannot meet a child’s needs.

Recommendation 2: Build Capacity to Reduce Reliance on Private Providers

NYC DOE should expand and rebuild its internal evaluation capacity. Across most of the country, school districts, particularly large urban systems, conduct the majority of special-education evaluations in-house. For example, the Los Angeles Unified School District conducts almost all special-education evaluations using multidisciplinary school-based teams. These teams evaluate within the context of district programs and IDEA’s LRE requirements.[62] In NYC, the reliance on private evaluators contributes to disparities between recommendations and what districts can legally or operationally provide, increasing the likelihood of disputes.[63] Expanding DOE-employed evaluation teams would increase the city’s ability to conduct timely, high-quality assessments aligned with available instructional models and help reduce unnecessary litigation.

Recommendation 3: Implement a Preschool Response to Intervention (RTI) Framework

NYS should support the creation of a structured, evidence-based Response to Intervention (RTI) or Multi-Tiered System of Supports (MTSS) framework for preschool across the state. RTI is a multitiered, evidence-based system that provides support to children and tracks their progress before determining whether a special-education evaluation is necessary.[64] Many states use formal RTI or MTSS systems in preschool to provide early intervention before a special-education referral is made. NYC’s preschool special-education system, built entirely on private providers, does not include a standardized RTI or MTSS process. Additionally, implementing a preschool RTI model would enable many children to receive early intervention in general-education settings, prevent overidentification, and ensure that evaluations occur only when necessary.

Recommendation 4: Adopt Mediation-First Approach to Special-Education Disputes

NYC should adopt a mediation-first approach to special-education disputes. Although mediation exists statewide, NYC uses it much less than other districts in New York or in other states. In most large districts nationally, mediation serves as a first-line alternative to litigation and resolves cases early without triggering pendency or protracted legal battles. NYC’s default of filing first and negotiating later, combined with automatic pendency for families already in private placements, has pushed the system toward escalating legal costs. NYC should adopt a mediation-first model housed within DOE, consistent with IDEA’s requirement that mediation be offered before a due-process filing. This would provide families with a faster, more collaborative, and cost-effective pathway to resolution, and would redirect many disputes away from hearings and settlements.

Recommendation 5: Strengthen Public School Programs to Reduce Inequities

Both the city and the state must address the inequities embedded in the current Carter-case system. Tuition-reimbursement cases are not equally accessible: many private schools require large deposits, and families must often carry costs during litigation. A system that depends on these hurdles will always favor families with more resources. It is critical to strengthen public programs to ensure that all children, regardless of background or resources, receive the education to which they are entitled under IDEA.

NYS already has authorized “Grow Your Own” initiatives to recruit and certify local community members and paraprofessionals into teaching and support roles under NYSED’s framework.[65] Therefore, NYC should leverage this existing mechanism to build an in-district force of special-education evaluators, teachers, and service providers, reducing reliance on private providers and ensuring that all students can access the same resources. Increasing this capacity would have the most immediate impact on ensuring that evaluations are completed under the required timeline and ensure that students receive their mandated services written into their IEPs.

Improving DOE capacity should include strengthening specialized public programs, including District 75. District 75 programs shape the overall continuum of services within NYC public schools. Shortages related to service providers, staffing instability, and limited access to evidence-based instructional models make it harder for schools to meet the needs of students with disabilities who require more specialized programs. Also, expanding capacity within District 75 would ensure that public programs are a high-quality option for students with more significant needs.

Conclusion

NYC’s reliance on Carter cases reflects a shift in how the city delivers special education. When private placements become the default, public schools lose the capacity that they need to serve students well. Families who are able to do so can navigate due-process secure placements that many others cannot access. And the core promise of IDEA—that every child will receive a free and appropriate public education in the least restrictive environment possible—breaks down. Reassessing Carter cases is not about taking services away from children. It is about ensuring that the services that they receive are consistent, equitable, accountable, and part of a system that can meet their needs without resorting to litigation. The billions of dollars that NYC spends on tuition reimbursement each year are not investments in instruction, program development, or long-term capacity building. Redirecting even a portion of that spending toward public school programs would strengthen the system for all students. This is an opportunity: to restore IDEA’s structure, rebuild public school programs, and ensure that all children in NYC receive an appropriate education in the setting where they can learn.

Endnotes

Photo: Elliott Kaufman / The Image Bank Unreleased via Getty Images

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).