Modernize the Criminal Justice System: An Agenda for the New Congress

Executive Summary

Crime, particularly violent crime, is a pressing concern for the American people. The surge in homicide and associated violence in the past three years has made voters skittish and prompted aggressive partisan finger-pointing. This increase has not, however, prompted significant investment in our criminal justice system. Ironically, as this report argues, this increase in violent crime is itself a product of fiscal neglect of that same system over the past decade.

Across a variety of measures, in fact, the American criminal justice system needs an upgrade. Police staffing rates have been dropping since the Great Recession; prisons and jails are increasingly violent; court backlogs keep growing; essential crime data are not collected; and essential criminology research is not conducted. These shortcomings contribute not only to the recent increase in violence but to America’s long-term violence and crime problems, problems that cost us tens of thousands of lives and hundreds of billions of dollars each year.

For too long, policymakers at all levels have failed to attend to this problem. Instead, both the political left and right have subsumed criminal justice issues into the larger culture war, fighting over the worst excesses of the police or the horrors of criminal victimization. Rather, they should look to past examples of federal policymaking in which lawmakers have used the power of the purse to dramatically improve the criminal justice system’s capacity to control crime. Doing so again could ameliorate many of the major concerns voiced by both sides in the criminal justice debate.

As such, this report proposes an ambitious, $12-billion, five-year plan to bring the criminal justice system up to date. It outlines proposals to:

- Hire 80,000 police officers;

- Dramatically expand funding of public safety research, including creating an Advanced Research Projects Administration for public safety;

- Rehabilitate failing prisons and jails with a carrot-and-stick approach;

- Create and propagate national standards for criminal case processing;

- Upgrade our data infrastructure, including by creating a national “sentinel cities” program.

Implementing these proposals would be a drop in the federal spending bucket, but they would likely have a dramatic and sustained impact on reducing the amount and cost of crime in America.

Introduction

Americans are worried about violent crime. In polling conducted before the 2022 midterm elections, 60% listed crime as “very important” to their vote, behind only “the economy” and “gun policy.”[1] Three in four voters described violent crime as “a major problem.”[2] In 2022, more Americans told Gallup they worried “a great deal” (53%) or “a fair amount” (another 27%) about crime than at any point since 2016. And Americans are more worried than they have been for much of the time after Gallup began polling the question in the early 2000s.[3]

These fears about rising violence reflect a real trend over the past three years. The national homicide rate rose 27% in 2020 and an additional estimated 4.3% in 2021.[4] Evidence from large cities suggests that homicides fell slightly in 2022 but remained significantly elevated over 2019 levels.[5] Homicide has risen almost as much in rural counties as in urban ones (although urban jurisdictions still account for the lion’s share of violence).[6] Rates of aggravated assault and automotive theft also rose steadily,[7] and in some major cities like New York and San Francisco, rates of property crime rebounded from 2020 lows to exceed 2019 highs.[8]

While these increases do not return the U.S. to the historic highs of the 1980s and 1990s, they represent a substantial and disturbing departure from the relatively low crime rates the nation enjoyed for most of the 21st century. Further, aggregate figures are misleading: many major cities experienced record homicide rates.[9] The increase was also worst for the most disadvantaged Americans.[10] In fact, homicide rates among young black men are near the peaks previously reached in the 1970s and 1990s (Figure 1). Among those most at risk of violence, things are essentially as bad as they used to be.

Figure 1.

Homicide Rate Among 15–34-Year-Olds, by Race and Sex (1968–2021)

These dramatic increases in homicide may be a product of many factors—Covid-19, the rise of anti-police politics following the murder of George Floyd, a surge in gun sales, etc. But they should also be understood in the context of a longer-term decline in the capacity of the American criminal justice system to effectively control crime. While this decline has been hidden for some time—obscured by both material and political conditions—the successive shocks of 2020 made the problem readily apparent.

The reality is that America’s criminal justice system is in dramatic need of an upgrade. Police staffing levels have been in decline for years; prisons and jails are growing more dangerous; criminal cases spend months or even years awaiting disposition; basic crime data are not being collected, and basic research is not being funded. Policymakers have ignored this steady decay, preferring to focus on culture war issues and so-called “criminal justice reform.” Meanwhile, the cost of all the crime not prevented likely runs to trillions of dollars; the time has come to take the problem seriously.

The ambitious investments and proposals laid out in this report should help to not only restore peace but make America’s criminal justice system one that the nation can truly be proud of.

America’s Criminal Justice System Is Out of Date

There are many and competing explanations for why certain kinds of crime increased in 2020, and why they have remained elevated. One straightforward explanation is that the increase was driven by a sudden, sharp reduction in the ability of the criminal justice system to control the level of crime. Courts closed, police retreated, offenders were diverted from jails and prisons—all these factors conspired to reduce the level of control exercised over would-be criminals.

In fact, a closer inspection suggests that events in 2020 simply exacerbated a long-running trend. Policing, courts, prisons, and jails are all underperforming based on a number of measures, and America’s high crime and recidivism rates and low clearance rates, particularly in the international context, suggest that the capacity of the system is well below what is socially optimal.

2020 Put an Enormous Strain on America’s Criminal Justice System

Events over the past three years have put remarkable strain on many American institutions, particularly the criminal justice system. The Covid pandemic and anti-police policies, stimulated by protests and riots, combined to produce a massive negative shock from which the country has still not fully recovered.

The onset of the Covid-19 pandemic in February and March of 2020 ground many of the system’s components to a halt. Police activity fell across major cities as officers prioritized social distancing over law enforcement.[11] Average backlogs in 476 criminal courts surveyed by Thompson/Reuters rose by nearly a third, with 57% of courts reporting an increase.[12] Court case clearance rates fell significantly across all states with available data.[13] Informal institutions of social control, like school and work, also shuttered, compounding the problem.

As these institutions ground to a halt, the number of criminal offenders on the street rose. Jails reduced their intake, with overall jail population falling 18% in March of 2020 and another 11% by April—declines from which jails have still not fully rebounded.[14] While public activity fell even more dramatically, reducing the number of opportunities for criminal offences, estimates adjusted for the decline in foot traffic indicate a 15 to 30% increase in the risk of being robbed or assaulted among those who did venture outdoors.[15] As another indicator of increased criminal behavior, homicides in April and May of 2020 saw increases of 20% and 24%, respectively, over the same months in the preceding year.[16]

Several months later, the murder of George Floyd by police officer Derek Chauvin brought thousands of protesters into the streets to call on their representatives to “defund the police.” The idea, proponents said, was to take funding from police departments and transfer it to other departments and agencies of local government, education, and transfer payments.[17] Though it rarely polled well,[18] the “defund” movement successfully pushed a number of major cities to slash their police department budgets and explicitly shifted the funds to activists’ preferred alternatives.[19] And in many more cities, police departments saw unprecedented spikes in resignations and retirements, reflecting a political environment more hostile to police and to proactive policing.[20]

Against this backdrop, it is little surprise that certain kinds of crime—homicides, shootings, car thefts—soared, even without adjusting for the Covid-induced decline in activity on the street. This surge has proved hard to recover from. Violence has remained at elevated levels even as Covid has receded and the country has reopened.[21] And at least in some major jurisdictions, other types of crimes have risen as well.[22] There is an obvious connection between this growth in crime and the sudden and sustained reduction in the capacity of the criminal justice system and the resources at its disposal. Some parts of the shock have begun to resolve—many courts are reopened, and public hostility to the police has decreased. But some of the changes have been durable—staffing shortages persist in many major cities, for example, in turn further reducing the number of police,[23] and jail populations remain below pre-2020 levels.[24] Further, the effects of a temporary shock on crime may outlast the shock itself, particularly because a spike in violence can spin off cycles of retribution for years afterward.[25]

The American Criminal Justice System Has Long Undersupplied Safety

The 2020 shock to the criminal justice system’s capacity was large and significant. But a closer inspection of the evidence suggests that the system has been flagging across a variety of indicators for some time, particularly since the onset of the Great Recession.

Police employment, particularly in big cities, has been, by many measures, in decline for more than a decade. The Police Executive Research Forum identified this “workforce crisis” in 2019, arguing that staffing had been falling since the Great Recession.[26] Figure 2 uses three data sources to give a sense of the trend: the Annual Survey of Public Employment and Payroll, a survey of local governments administered by the Census Bureau; the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages, a survey of public and private employers administered by the Bureau of Labor Statistics; and the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) system, which receives voluntary data on crime and police employment from police departments nationwide.[27] The latter shows two UCR measures—one, labeled “constant,” contains only cities that report staffing figures in every year across the whole period (abbreviated as “Const. UCR” in Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Sworn Officer Employment per 1,000 Americans (1985–2021)

Regardless of which source one picks, the underlying trend appears to be the same. Police employment ratios rose steadily through the 1990s, plateaued through the early 2000s, and began declining right around the Great Recession. In the most recent years available (2020 for the constant data, 2021 otherwise), police-to-population ratios have fallen by between 4.9% and 12.8% relative to 2009.

American police face another, even longer-term problem: an inability to solve crimes. Even before 2020, police departments consistently cleared less than half of violent crimes and less than 20% of property crimes.[28] Even homicide, the most serious offense, and the one to which investigators generally dedicate the most attention, was solved only about 60% of the time.[29] These rates, furthermore, have been declining steadily for decades, leaving millions of crime victims without a resolution to their case—and thousands upon thousands of offenders on the street as a result.[30]

America’s prisons and jails are struggling as well. The absolute number of prisoners has been declining steadily since the Great Recession, a product of crusading reformers and fiscal constraints. Yet as of the end of 2021—after both the slow pre-2020 decarceration and then a sharp 16% reduction in the population over two years—24 states and the federal government still have prison populations over 90% of the lower bound for overcrowding; 12 have populations over 100%.[31] Mortality rates, meanwhile, have steadily risen in both prisons and jails, driven by suicide, homicide, and drug overdose (Figure 3).[32] Some jails are at their highest levels of in-custody death on record.[33] That gangs are endemic to many of America’s prisons further compounds these problems.[34] The California prison system, for example, is effectively governed not by the California Department of Corrections but by racially segregated gangs.[35]

Figure 3.

Non-Medical Deaths in U.S. Prisons and Jails (2001–2019)

American prisons also do a poor job rehabilitating their residents. Cohort studies suggest that between one-quarter and one-half of those released from prison will reoffend within five years.[36] This is due in no small part, despite decades of alleged commitment to the “rehabilitative ideal,” to a dearth of high-quality information about how to rehabilitate someone in a prison context (or if we even can). Much of the research is old, uses low-quality designs, lacks adequate follow-up periods, or is contaminated by too-small sample sizes and publication bias.[37] As professor James Byrne notes in the review he was commissioned to write as part of the FIRST STEP Act, a major federal prison reform bill, there has been exactly one serious evaluation of a federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) program.[38] We struggle to rehabilitate, but we do not even know how to do it.

The slowdown of the court system, though exacerbated by Covid, is also not new. A National Center for State Courts (NCSC) study of 136 courts in 21 states found that courts systematically underperformed national model standards for timeliness. For example, just 30% of felony cases were disposed of within 90 days, compared to a goal of 75%.[39] Such delays mean offenders spend longer times in jail, contributing to overcrowding, increasing the risk of a criminogenic jail experience, and slowing the delivery of justice. Delays also waste prosecutors’ and defense attorneys’ time, making the whole system slower still.

NCSC’s analysis suggests that this problem emerged in recent decades. While total felony caseloads rose steadily through the 1980s and 1990s, the median time from arrest to sentencing was essentially constant. Yet between 2000 and 2006, that median time rose 78%, even as felony caseloads were roughly constant. “Caseflow management practices had deteriorated such that courts could not manage the increasing caseload,” the NCSC notes. “Knowledge thought to have been institutionalized had apparently retired along with the judges and court administrators who held it.”[40] These findings are elaborated on below.

The problems of the criminal justice system extend beyond the courts, prisons, and police. Our method for collecting data on crime is woefully antiquated. Since 1929, the FBI has collected data on crime through its Uniform Crime Reporting program (UCR). While the UCR numbers are widely used, however, they have known limitations. Participation by state and local jurisdictions is voluntary and fluctuates over time, making trends hard to assess. Agencies often do not report in comprehensive detail, or do not report month-to-month data.[41] The rules of UCR reporting, particularly through the Summary Reporting System (SRS), which was until recently the standard, also required the reporting of only the most serious offense in a multi-offense crime—meaning, for example, that if someone shoots someone else in the course of committing larceny, only the gun assault is reported. This artificially limits the number of less-serious crimes counted. SRS also contained limited details about many of the circumstances of a crime, including the relationship between the victim and the offender.[42]

To address these issues, the FBI developed in the 1980s a new, much-more detailed reporting standard called the National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS).[43] In 2015, it began sunsetting SRS, doling out $120 million to help departments transition to the new system; in 2021, the agency stopped accepting non-NIBRS data.[44] But the transition was unsuccessful: 7,000 agencies, covering about 35% of the U.S. population, did not report.[45] That included not just small police departments but eight cities with a population of more than a million, including New York City.[46] As a result, the FBI’s estimates for crime in 2021 come with massive error bars, producing numbers too unreliable to be useful.[47] The problem will persist for 2022 figures: as of April 2022, 31 states had not yet fully transitioned to NIBRS.[48]

Most departments will eventually switch to NIBRS, though cities like San Francisco might not be there until 2025.[49] But even then, big holes will likely remain in the FBI’s reporting programs. The FBI began collecting data on officer use-of-force incidents in 2019, for example, but just 41% of agencies participated in the first year.[50] In fact, the program may be at risk of shutting down, because it has consistently failed to meet its targets for participation.[51] Data on hate crime offenses are also chronically underreported, making it one of the least reliable data sets despite its wide use.[52] The FBI reported that anti-semitic hate crime fell in 2021, for example, even as third-party analyses identified instead a massive increase.[53] And even after NIBRS, data will still be reported on a months-to-years lag, rendering it useless for real-time crime trend forecasting.

A last area of inadequacy is in criminal justice–related research. Given the exorbitant costs of crime, research into its reduction almost certainly yields substantial benefits—unsurprising given the observation that R&D funding yields one of the better cost/benefit ratios of government spending categories.[54] The Department of Justice primarily funds research through the National Institute of Justice (NIJ), which doled out roughly $76 million in research funds out of an operating budget of $232 million in FY 2018.[55] This funding level is paltry, however, in both historical context and relative to other government agencies.

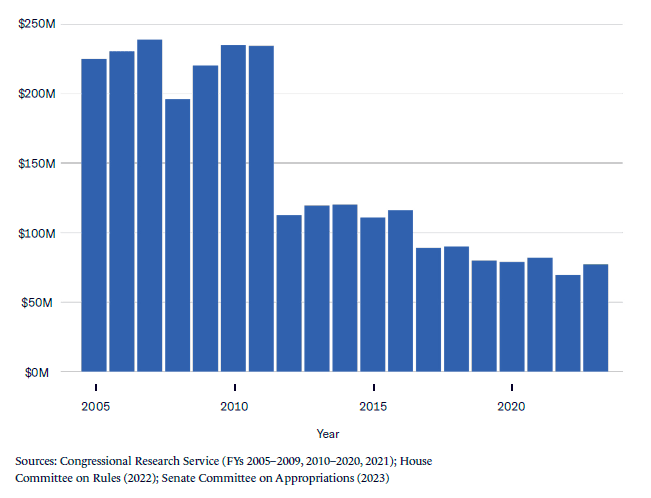

Figure 4 shows total spending by the Office of Justice Programs (OJP)—the DOJ office that oversees NIJ—on “research, evaluation, and statistics,” money which goes both to NIJ and the Bureau of Justice Statistics. In both nominal and real terms, funding has plummeted in recent years, down 68% from its peak in 2007. FY 2012, in particular, saw a significant reduction in the budget, without any obvious substitution to a different budget function within OJP.[56] House Democrats, then in the minority, criticized House Republicans’ efforts to reduce research funding, writing in their minority report on the Appropriations Committee report that, “the collection and dissemination of criminal justice statistics and research on ‘what works’ in criminal justice are arguably the most fundamental role for the federal government in helping state, local and tribal governments improve criminal justice systems. Yet, the bill cuts funding for the National Institute of Justice by 14 percent and cuts the Bureau of Justice Statistics by 22 percent.”[57]

Figure 4.

Office of Justice Programs “Research, Evaluation, and Statistics” Nominal Funding (FYs 2005–2023)

The NIJ is also dramatically underfunded relative to other agencies that hand out funding. It does not merely spend less than the National Institutes of Health, with its annual budget of $45 billion.[58] It receives even less funding than many of NIH’s component agencies, including the National Institute for Dental and Craniofacial Research ($483 million in FY 2021) and the National Institute for Minority Health and Health Disparities ($390 million).[59] Homicide killed 24,576 people in 2020, while eye disease killed 52.[60] Yet the National Eye Institute’s FY 2021 budget was more than three and a half times as much as NIJ’s FY 2018 budget (the last reported figure).[61]

This relatively low level of funding dramatically limits the number of grants NIJ can issue. For example, in FY 2018, NIJ made just three awards, totaling just $1.7 million, to “understand the impact of police strategies,” and four awards, totaling $2 million, for “reducing firearms violence.” NIJ funds evidence modernization (e.g., DNA technology) through the Paul Coverdell National Forensic Science Improvement Grants; this program hands out only about $15 million a year, likely leaving thousands of departments without much-needed technology.[62]

In short, the key components of the criminal justice system—the police, prisons, jails, courts, data-collection apparatus, and research and development—are operating well below optimal capacity. This problem predates the 2020 violence wave, which has only made the dysfunction more apparent. But if our criminal justice system is less effective than it could be, then there are almost certainly crimes not being prevented and public safety benefits being left on the table. Our spending deficit in this area exists not merely by comparison to how low crime has been but to how low it could be.

This undersupply of public safety is most apparent in an international context. By comparison to basically any other developed country, violence levels in the U.S. are intolerably high. The raw numbers are telling: in 2021 alone, there were at least 4.5 million violent crimes, including nearly 25,000 homicides.[63] Among 34 OECD countries for which data are available, the U.S. has the fourth-highest homicide rate, behind only Mexico, Colombia, and Costa Rica. It also has the fifth-highest rate of serious assault and rape among reporting countries.[64] One study estimates that the firearm homicide rate in the U.S. is 25 times that of other developed nations.[65]

The costs of all this crime are substantial. One estimate finds that total crime in 2017 alone—when rates of homicide, shootings, and other particularly costly crimes were much lower—imposed $620 billion in monetary costs, as well as an additional $1.95 trillion in quality-of-life losses.[66] These high costs are likely borne at the individual level. Analysis using data from the Netherlands finds that being the victim of crime—including both violent and nonviolent offenses—makes individuals less likely to work and more likely to take government benefits. Those effects are both large (up to a 13% drop in earnings) and durable (persisting for at least four years).[67]

The U.S. has a reputation for being excessively punitive compared to peer nations. Indeed, it incarcerates more people per capita than any other OECD country,[68] but total carceral capacity is just one measure of the strength of our criminal justice system. The U.S. has far fewer sworn police officers per capita, particularly per homicide, than other developed nations—a ratio that may help explain our high incarceration rate.[69] Because policing is local in America, access to its benefits is also more unevenly distributed, with “poor and heavily-nonwhite jurisdictions employ[ing] far fewer officers per crime than wealthy and white jurisdictions do,” one scholar finds.[70]

To put this in stark terms: every year, thousands of Americans die, and millions more are victimized, because we do not do enough to control crime. There are, of course, both natural and moral limits on how much the government can do to address crime as a social issue, but the American criminal justice system is well short of those limits, and has been for some time. These shortcomings are a product of a system in substantial need of an update.

The Time Has Come to Modernize the Criminal Justice System

Criminal justice policy has taken one of two tacks over the past 60 years. For much of the latter half of the 20th century, the focus was on increased punitiveness—harsher sentences, more aggressive policing, etc. While this sometimes meant more funding, the primary focus was on increasing severity, rather than capacity per se. For much of the 21st century, meanwhile, the focus has been on “criminal justice reform,” the idea that the criminal justice system is broken, and that what is specifically required is placing more constraints on its operations—more oversight, more regulation, and a reduction in its reach. The priority for policy is to ratchet back the punitive part without attending to the capacity of the system more generally.

This report has so far emphasized a different factor: capacity. The criminal justice system does not need to be more or less aggressive. It needs more capacity, independent of the level of aggressiveness. Many of the system’s most important components are long overdue for an upgrade. They are doing far less than they could do, relative to historic norms and relative to our international peers. And Americans are paying the price, especially the most disadvantaged among us.

As the rest of this section argues, this stance departs dramatically from how both the left and right have tended to think about the criminal justice system. However, it is well within the capacity of government to shift its posture, focusing less on “reform” or “punitiveness” and more on creating a modern, effective system. Because it breaks from the current paradigm, this kind of “upgrade” has the potential for bipartisan support.

Austerity Thinking Currently Defines Our Approach to the Criminal Justice System

There are many governmental jurisdictions—federal, state, and local—in the U.S., but they do not spend that much on fighting crime (Figure 5). Between 1959 and 2021, Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) data show all “public order and safety” spending accounted for between 3.5% and 6.7% of total government spending across all budget functions. Spending share peaked in 2002, remaining just below 7%, until 2009. It dipped, however, following the Great Recession, dropping to just below 6% between 2010 and 2019. Finally, it fell further in 2020–2021, as Covid-related spending massively inflated the denominator of that calculation.[71]

Criminal Justice Functions as a Percentage of Aggregate Government Spending (1959–2021)

Spending on the criminal justice system, in other words, is retreating as a priority for government. The dramatic increase in spending share between the mid-1980s and early 2000s captures government response to the great crime wave (spending detailed further below). But since the culmination of the “war on crime,” other budget items have taken a higher priority.

This prioritization is, of course, the product of many factors, but it is, in part, the result of a peculiar ideological alignment around criminal justice priorities that developed in the late 2000s, one which joined progressive distaste for the criminal justice system with conservative concerns for fiscal austerity and libertarian skepticism of the state.

Progressives have long been critical of the American criminal justice system, which they see as needlessly punitive, racist, and classist, and not sufficiently therapeutic; some more radical critiques view the entire system as a bankrupt system of social control. These long-standing currents in the American left, however, gained increasing ground in the 2000s, as the swiftly plummeting crime rate allowed them to shift national focus from crime to the scale of mass incarceration and the worst behaviors of American police. Books like The New Jim Crow advanced the thesis that “mass incarceration” and the “War on Drugs” were blights on America’s moral reputation. The Obama administration, arguably the most progressive on criminal justice issues in 40 years, took this message to heart.[72]

For the first time in decades, the decarceral agenda found bipartisan support. Red-state Republicans pushed to decarcerate and reduce sentences;[73] prominent conservatives went after mandatory minimums, which had once been a major movement agenda item.[74] This shift reflected, in part, the movement’s libertarian turn in the Tea Party era, and conservative advocates for criminal justice reform often made their arguments using the same anti-state rhetoric with which they attacked the IRS or EPA. But part of their argument was also fiscal: policing and punishing people is expensive, and doing less of it would save the taxpayer money.[75] This argument was doubtless particularly persuasive after the Great Recession put a hole in state and local budgets[76]—that police employment and incarceration rates fell after 2009 is almost certainly no accident.

This chance confluence of priorities produced some odd outcomes, as, for example, when infamously tough-on-crime Donald Trump made bipartisan criminal justice reform one of his administration’s top priorities. But more significantly, it put both left and right on strange ground, ideologically speaking. The left began making the argument that a fundamental function of government would be improved by slashing its funding and dramatically reducing its responsibilities, especially if those responsibilities could be handed back to “community groups.” This positioning, which culminated in the “defund the police” movement, found the left embracing a logic of austerity that it would reject in essentially all other contexts. The right, meanwhile, found itself disclaiming exactly the strategies—broken windows policing, mandatory minimums, etc.—it had endorsed less than a generation prior. More generally, it yielded to the idea that the problem wasn’t crime but rather the criminal justice system, and that the reform of the latter should take priority over keeping the former under control.

The problem here is not just that the criminal justice reform consensus turned each side on its head. It is that in the process of trying to fix the system, left and right became blind to its declining capacity. Progressives should see spending on the criminal justice system as at least as sensible as spending on other forms of government service provision, especially if added spending does not come with increased rates of punitiveness. Conservatives, meanwhile, should have been concerned about the government’s underprovision of safety, the one good essentially all conservatives think the state should provide. Because the consensus was that the system was the problem, however, its maintenance and expansion became less of a priority than increasingly radical reforms.

Increasingly, both left and right are seeing the error of their previous prioritizations. In particular, as violent crime has surged, many on both sides of the aisle are asking if the criminal justice system is doing enough to provide safety. The answer, as reviewed above, is no. And the correct solution is for government, particularly the federal government, to take significant steps to strengthen it.

The Federal Government Has Historically Played a Role in Supporting the Criminal Justice System

Policing in America is a peculiarly local institution. There are 43 distinct police departments in the United Kingdom and only 19 in Germany; there are somewhere between 14,000 and 18,000 in the U.S., depending on whom you ask.[77] Most police spending happens at the local (i.e., city/ county/township) level rather than state or federal,[78] but the scale of the challenge involved in modernizing the criminal justice system means that local governments are unlikely to be able to make the leap alone. Federal action, through dollars, mandates, and coordination, will be necessary to bring the system up to speed.

Such action is hardly unprecedented; the federal government has in the past responded to crime waves with significant investments in the criminal justice system. In 1968, when the violent crime rate was rising but still far lower than it is today, President Lyndon Johnson called for a “war on crime” to parallel his War on Poverty.[79] Congress responded with the bipartisan 1968 Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act.[80] Designed, in part, “to assist State and local governments in reducing the incidence of crime,” the bill created the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration (LEAA), which provided states with funds to train law enforcement, do criminological research, and expand carceral capacity.[81] The bill moved “about $55 billion in inflation-adjusted dollars to the states to combat crime” before Congress eliminated it in 1983.[82]

The 1994 Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, signed as the crime wave was peaking, was the largest crime bill in the country’s history. It provided for 100,000 new police officers and allocated $9.7 billion for prisons and $6.1 billion for prevention programs.[83] It replaced the LEAA with the Community Oriented Policing Services Office (COPS) within the Department of Justice, which handed out $14 billion over the following 20 years.[84] Like the Safe Streets Act, the crime bill was advanced with the support of a Democratic president (Bill Clinton) and passed on a bipartisan basis, thanks in large part to the hard work of then-senator and future president Joe Biden.[85]

These actions highlight what the federal government can do: provide funding and coordination to help local police departments maximize their potential. The federal government can also set standards and collect data—vital functions for expanding the capacity of our system further.

Enhancing Criminal Justice Capacity Can Satisfy Both Sides’ Concerns

To this point, this brief has argued that partisans on both the left and right are focusing on the wrong problems in the criminal justice system, and that they should instead focus on expanding its operational capacity. It is worth emphasizing, however, that investing in the criminal justice system can also indirectly address several concerns that both left and right have about the system as currently constituted.

For the left, many concerns can be subsumed under the general rubric of fair and humane treatment of people suspected of, charged with, convicted of, or serving time for crimes. Some progressive advocates argue, in fact, that giving more funding to the criminal justice system will serve only to reinforce practices they see as inhumane. The opposite, however, is true. More investment in police hiring means departments can be more discriminating, avoiding “wandering cops” and other “bad apples.”[86] It also reduces the burden of overtime, which contributes to stress and burnout that can drive police misconduct.[87] Slow courts and poor prison conditions are not essential features of either institution—the courts have been faster, and other nations’ prisons have ostensibly higher quality, suggesting that change is possible with sufficient investment and political will. Better collection of data and more funding of research, meanwhile, can also advance reform goals, allowing the system and policymakers to become smarter by providing more information about where to target reform.

On the right, there is a knee-jerk tendency to prioritize severity over investment, but a better-funded criminal justice system almost certainly increases the swiftness and certainty of consequences, in turn enhancing deterrence—possibly more so than additional marginal severity.[88] More cops on the street and faster courts means more offenders are deterred and more swiftly incarcerated; money spent on research and data is likely returned in marginal crime reduction. Conservatives are often wary of making investments in the criminal justice system, but even the most ardent right-winger believes that public safety is a legitimate function of government—they can justify spending on it, if nothing else.

Some might criticize this argument as implausibly rosy: we can have more safety and more reform? But the key insight is that investment in the capacity of the criminal justice system means that it can do more on all fronts, becoming more effective and fairer. Federal action on criminal justice capacity helps reconcile the left and right’s often conflicting priorities, making the system better for everyone involved.

A Blueprint for a 21st-Century Criminal Justice System

But what, exactly, could the federal government do to modernize our system? This section lays out proposals for the five components of the system—policing, courts, prisons, data, and research—discussed previously. Specifically, it envisions allocating $12 billion over the next five years, equivalent to increasing annual federal criminal justice spending by just 3.5%.[89] The bulk of this funding—$10 billion—would go toward police hiring, with the goal of hiring 80,000 new police officers nationwide to restore staffing ratios to pre-Great Recession highs. Another $500 million would be allocated for prison remediation. Lastly, $1.5 billion would go to the Office of Justice Programs for research, evaluation, and statistics. Those funds would cover a dramatic expansion in research funding, as well as funding for establishing national standards for criminal case management and setting up a “sentinel cities” program for timely crime-data reporting.

The common denominator of these proposals is the focus on improving the efficacy of each component, as opposed to increasing punitiveness or curtailing functionality. A better, more effective criminal justice system should be a bipartisan goal, and the proposals below envision a way of achieving it.

Supercharge Hiring of Local Officers

The federal government spent roughly $50 billion on police in 2021.[90] Most of that spending, however, went toward the various federal law enforcement agencies—FBI, DEA, ATF, etc. The primary source for federal funding of local hiring is the Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS) office within the Department of Justice. The COPS office is authorized to dole out just $324 million in hiring grants in FY 2023, of which nearly $100 million is reserved for programs not directly related to hiring.[91] In other words, the federal government spends relatively little on hiring local police officers.

This was not always the case. COPS was created as part of the 1994 crime bill. Between FY 1995 and FY 1999, it received annual appropriations averaging $1.4 billion in service of President Clinton’s goal of putting 100,000 new cops on the street.[92] The effects of this cash infusion can be seen in Figure 2. Funding declined in the new millennium but was reinvigorated by a $1 billion budget line in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, an effort to help local police departments stave off the effects of the Great Recession.[93] In spite of this spending, police staffing ratios have steadily dwindled since that time (again, see Figure 2).

A large and persuasive body of evidence finds that these grants, and the cops that they hire, reduce crime. Research examining the size of COPS grants, cut-offs for eligibility, and other variations in COPS awards consistently finds the program significantly reduces both property and violent crime.[94] One estimate indicates that each hired officer prevents four violent and 15 property crimes, while another finds that a 10% increase in police employment reduces violent crime rates by 13% and property crime rates by 7%.[95] Various analyses suggest that each additional dollar dedicated to COPS hiring generates between $4 and $8.50 in added social value, and that while an additional officer-year costs roughly $169,000, it generated $352,000 in social benefit.[96]

It should be clear, then, that expanding the program would generate outsized social gains, but by how much should it grow? The U.S. appears to have between 680,000 and 770,000 sworn officers, equivalent to 2.1 to 2.4 officers per thousand people (again, see Figure 2 and attendant data). Just before the Great Recession, it had been between 2.4 and 2.5 sworn officers per thousand people. Given a national population of 330 million, to return to prior ratios would mean a total officer population of 790,000 to 825,000 officers, or an increase of between 20,000 and 145,000 officers, depending on target and baseline. Assuming a cost per officer of $125,000, that would total between $2.5 billion and $18.2 billion.[97]

Splitting the difference yields an allocation of $10 billion, or $2 billion per year for five years, for added COPS hiring. That would be enough to fund 80,000 new officers under optimal cost assumptions, increasing staffing ratios to between 2.3 and 2.6 officers per thousand Americans. Ten percent of these funds—$200 million per year—could be designated specifically for hiring or training new detectives, a proven way to increase clearance rates and reduce crime.[98]

This is a large outlay, although it represents a less than a 4% increase in federal spending on police generally. Funding of such a scale was necessary to bring staffing up to pre-Great Recession levels; recall that COPS received an average of $1.4 billion in funding in FYs 1995 through 1999. Adjusted for inflation, this was equivalent to about $2.4 billion today. Furthermore, investments in more policing will, as discussed above, pay off, particularly in reduced social costs of crime.

One way to maximize the impact of these funds would be to revise the law to permit more money to be dispersed to large jurisdictions. Under current rules, half of funds awarded by the Department of Justice must go to jurisdictions with a population of fewer than 150,000 people.[99] While it’s important not to leave small-town America out, the reality is that crime levels and rates are higher in urban areas than rural ones, and areas with higher populations will, all else being equal, simply have more crime.[100] It makes little sense, then, to assign the same amount of money to a city with a population of 10 million as to a town with a population of 10,000; the former needs more cops than the latter.

Foster Innovation in Criminal Justice Policy

Criminology is not a new discipline. Its earliest texts date back to the 18th century.[101] But it is only in recent years that criminology has really been able to tell policymakers something about what they can actually do to reduce crime. It was not until the late 1990s, for example, that studies using rigorous methods discerned that hiring police officers causally reduced crime; prior research, inescapably tainted by simultaneity bias, had reached only the unsurprising conclusion that as the crime level goes up, so does the number of police officers.[102] While some policing strategies are now supported by modest bodies of research, even these are not without dispute.[103] As discussed above, the situation in corrections is even worse. Similarly, many “alternatives” to the police, which have in recent years received millions in government funding, are lacking in evidentiary support.[104]

Yet, as discussed previously, funding dedicated to criminal justice research is well out of proportion to the social costs of crime, has been inexplicably declining, and is well below funding for other government research initiatives. Modernizing the criminal justice system means taking concrete steps to remediate this issue and to improve the returns on NIJ’s investments.

First and foremost, that would mean expanding NIJ “research, evaluation, and statistics” funding past pre–Great Recession norms. In 2007, OJP received $238.3 million for this function, equivalent to roughly $336 million after adjusting for inflation, or an increase of $254 million over FY 2022 levels. Increasing that spending slightly, to $400 million in annual funding, would yield an additional amount (i.e., inclusive of current funding levels) of approximately $1.5 billion over five years.

Some of this funding would be set aside for the “sentinel cities” and “national case-management standards” projects discussed below, but the lion’s share would go to NIJ to invest in crime prevention research, including but not limited to:

- Policing strategies for reducing violence and/or crime;

- Rehabilitation and prison disorder reduction;

- Crime prevention through environmental design;

- Community violence interruption and community-based crime prevention.

Funded studies would adhere to high standards for research, with randomized designs, pre-registered outcomes, required data sharing, and transparency about funding. These funds would be allocated to research scientists who can be held accountable for accurately measuring results—they should not be dispersed to practitioners, community organizations, or other entities who will use funds to advance their ideological or organizational agendas. At the same time, these are experimental funds, which means they allow for the testing of as-of-yet-unproven techniques, like community violence intervention, which may still contribute to public safety.

Both the National Academies and the DOJ Inspector General have raised questions about the effectiveness of NIJ’s operations.[105] While NIJ has made strides in recent years, according to both it and the IG, any substantial funding bump should be tied to structural changes that encourage the production of faster, more useful research.[106] That means a review of NIJ’s efficiency, but it also means that policymakers should consider how to get more bang for their R&D buck. “Metascience”—the scientific investigation of the production of scientific knowledge, including an eye toward improving that production—is an underattended issue in R&D policymaking.[107] NIJ needs more funding, but it also needs to experiment with how to use that funding more efficiently.

One possible approach to fostering innovation is to replicate the model of the Defense Advanced Research Projects Administration (DARPA), the agency within the Department of Defense whose experimental funding created the internet, guided missiles, and many personal electronics. DARPA is characterized by “a flat organization that empowers its tenure-limited program managers with trust, autonomy, and the ability to take risks on innovative ideas.”[108] This structure permits DARPA to make high-risk, high-reward bets on innovative research, counteracting the natural conservatism of government funders.

A similar institution, ARPA-Health, now exists at the National Institutes of Health. One approach to diversifying NIJ’s research portfolio, similarly, could be to create a separate department, ARPA-Justice. ARPA-J would be given a fraction of NIJ’s annual research budget. A tenure-limited administrator would have limited time but mostly unfettered discretion with the charge to invest in innovative technologies and practices that could have a dramatic impact on public safety. Given the relative youth of criminology as an academic field, there is likely a fair amount of “low-hanging” fruit that ARPA-J funding could “pick.” Further, within-institution competition can also foster innovation across the whole organization, and ARPA-J’s successes could be replicated by NIJ as a whole.[109]

A second approach to innovation is to more deliberately consider the trade-off between time expended on grant writing and grant amount. NIJ grant proposals require extensive information on the planned project, with grantees spelling out minute details.[110] While this is standard practice in government grantwriting, it may contribute to the exorbitant time principal investigators spend on proposals rather than on actual research.[111] In the case of public safety, more time spent on research really can mean fewer lives saved.

NIJ, then, could consider looking to the innovative grantmaking undertaken during another life-or-death situation: the Covid-19 pandemic. In the early months of the pandemic, top researchers found themselves stymied by the slow grant-making process at NIH. In response, a group of non-profits and wealthy individuals began funding “fast grants,” $10,000 to $500,000 disbursements with turnaround times of at most 14 days.[112] Fast grants eventually distributed $50 million in over 260 grants, funding innovative Covid tests, clinical trials for repurposed drugs, and rapid tracking of the disease’s new variants.[113]

Again, the model here is to make many investments, with the assumption that only some will pay off. But secondarily, the insight is that small grants do not necessarily need the same degree of detail as large ones. NIJ should therefore consider adopting a scaled grant proposal process. Small grants—say, $25,000 and under—should require far less paper work than medium-sized ones, which should in turn require far less paper work than large ones. Moving money out the door quickly can expedite the scientific process, hastening public safety returns.

Both of these proposals are aimed at making NIJ adopt a more innovative mindset. Combined with added funding, this approach could dramatically improve our knowledge of how to fight crime and, in turn, produce substantial social savings in the long run.

Accelerate Case Disposition

As previously discussed, many courts have experienced dramatic increases in processing time over the past three years, resulting in backlogs that delay justice. At least by some measures, this slowdown is part of a longer-term trend.

Accelerating case disposition in criminal cases is something of a win-win-win. It is a win for criminal defendants, because they spend less time in jail. It is a win for the public, which spends less on detaining these individuals and the costs of lengthy cases. And it is a win for public safety, because the swiftness of punishment is generally thought to be a key component of deterrence.[114] The faster cases are disposed, the more effective the law will be at deterring crime.

But making cases move faster through the justice system—expediting “case management”—is easier said than done. Between 2016 and 2018, the aforementioned researchers with the National Center for State Courts gathered data on nearly 1.2 million cases from 136 state trial courts in 91 jurisdictions in 21 states, the first such study of its kind in over 30 years. They found, to reiterate, that courts routinely fell well behind the national model time standards for case disposition. The median case took more than five months to dispose, and as many as 17% of cases were not disposed of within a year.[115]

Remarkably, most factors did not contribute to the length of cases. That included “court and community factors,”—including “size of court, method of judicial selection, type of calendar, number of filings per judge, length of presiding judge term, or availability of case-management reports”—as well as case-level factors, like the type of case, manner of disposition, and number of charges on the case.[116] Instead, the NCSC researchers found that the most important predictors were the number of hearings held and the number of continuances (i.e., court-granted delays) (Table 1). In felony cases, each continuance meant a case ran a predicted 21 days longer in the NCSC model; for each hearing held, 14 days. Only the case involving a homicide or going to trial had a larger impact. A similar trend was found for misdemeanor proceedings.

Relationship Between Felony Case Characteristics and Time to Disposition

“More timely courts better maintain control over scheduling and reduce both the number of continuances and the time a continuance or an additional hearing is allowed to add to the schedule,” the NCSC analysts concluded.[117] Seven top performing courts, with which the NCSC did extensive follow-up, were characterized first and foremost “by a commitment by the bench to active case management”—keeping cases flowing.[118] In other words, the project concluded that the best thing that courts can do to reduce the backlog is to schedule hearings purposefully and minimize the use of continuances.

Researchers reached a similar conclusion in a 2019 pilot study of active case-management practices in Kings County (Brooklyn), New York. They concluded that case delay was driven largely by lengthy adjournments, “unproductive” court appearances, and other scheduling challenges. To address this, they implemented a three-part program: establish a formal timeline to which cases will stick; minimize adjournment lengths; and require case conferencing between defense and prosecution to help facilitate speedy resolution. Cases that adhered to this program took roughly 22% less time to resolve, on average, with 28% more disposed within six months of indictment.[119]

These findings are unsurprising. There may be deeper “root” causes, but American courts move slowly because they do not do enough to move quickly. Both defense and prosecution, criminals and society, have an interest in seeing this remediated.

But what can federal policymakers do to help encourage better case flow? Within the federal court system, they can collaborate with the Judicial Conference of the United States, the body established by Congress that considers administrative and policy issues affecting federal courts, to ensure that all federal courts are adhering to best practices in scheduling, minimizing continuances, and scheduling efficiently. Ensuring adherence, though, is likely better facilitated by the administrators of the judicial branch rather than by Congressional fiat. The federal judiciary is also currently in the process of modernizing its Case Management/Electronic Case Filing system; ensuring that that undertaking is fully funded will keep the federal judiciary running smoothly.[120]

Affecting the behavior of state courts is more challenging. State courts receive federal funds both in direct grants and in pass-through dollars.[121] Direct dollars do not appear to account for a significant proportion of court funding,[122] though the influx of cash under the CARES Act and other Covid transfers may have changed that balance in recent years.[123] Further, attempting to affect what is basically a non-monetary problem—judges don’t stick to their calendars—primarily through monetary incentives seems suboptimal.

Perhaps the best approach would be to charge the Office of Justice Programs and National Institute of Justice, ideally in collaboration with the Judicial Conference of the United States and the NCSC, with clearly articulated and propagated guidelines for timely case disposition. A small outlay would cover research costs. National standards would at least give judges a sense of what rules to follow to minimize case delay.

DOJ could also work with the NCSC to assess what, if any, fiscal constraints limit the ability of state courts to adhere to ideal case processing standards. It could then recommend to Congress where and how it can make targeted investments in local courts to meet the goals of the aforementioned national standards. The size of this latter outlay is, necessarily, currently unknown, but the benefits of having such clear standards that are shared among all parties in the criminal justice system are likely substantial.

Make the Prison System Work

Some 1.2 million people were in American prisons as of the end of 2021. That represents a marked decline, in both absolute and per capita terms across multiple states, from the peak of mass incarceration.[124] That decline is, in turn, a product of more than a decade of deliberate decarceration, arguably the most significant impact of the “criminal justice reform” movement. Advocates support population reduction on fiscal grounds—housing prisoners is expensive, building new prisons more so—and because, they contend, declining crime rates make incarceration less necessary. In some cases, they also argue that prisons will always be dangerous, decaying, traumatizing places, and so as few people should be exposed to them as possible.

At the margins, reducing prison population is a legitimate approach to limiting the costs and harms of prison, but hard facts will eventually limit this approach. As of the end of 2020, 62% of state prisoners were incarcerated for violent offenses. Many of the remainder were in on burglary (8%), drug dealing (9%), or weapons charges (4%).[125] If released, many would likely reoffend—three in four state prisoners are rearrested within five years of release, BJS data based on a 2008 cohort of prisoners show.[126] American prisons are full of serious offenders, whose release is not necessarily in the public interest.

If decarceration cannot remediate all of America’s prison problems, then the only option left on the table is investment: if we cannot empty the prisons, we should make them better. The federal government currently spends relatively little on prisons, about $7 billion in FY 2021. That figure is, variously, 10% of all federal public safety spending,[127] less than 7% of all spending on prisons nationwide (including state and local government spending),[128] and 0.1% of federal spending generally.[129]

Building new prisons is prohibitively expensive—running to the hundreds of millions[130]—particularly as prison populations are declining from their peak. But there is room for modest investments in prisons, on the order of $500 million over five years, without dramatically expanding total outlays (roughly a 7% increase in federal prison spending). Those investments would focus on improving prison order, to reduce violence, drug use, and associated deaths. Further investments, funded by NIJ’s expanded budget, should focus on critical research into rehabilitation best practices.

That America’s prisons are disorderly is evident from the recent rise in prison and jail deaths (see Figure 3). At the same time, violence is not a universal feature of prisons, either internationally or across American prisons. Population composition—how old, how serious, and how gang-involved—can affect a prison’s violence risk, as can the quality of governance.[131] While the total number of prison homicides in 2019, 149, represents a 15% one-year increase, it also means that most of the 1,668 state and federal prisons saw no homicides in that year.[132] In other words, the problem almost certainly is focused in particular prisons, which means a one-size-fits-all solution is inappropriate. Rather, the Department of Justice needs to identify problem actors (using data already collected by the Bureau of Justice Statistics) and improve their performance individually.

A more aggressive federal oversight regime for the BOP has already been envisioned in the 2022 Federal Prison Oversight Act, which would charge the inspector general with assessing the dangerousness of BOP facilities and create a separate ombudsman responsible for investigating complaints within the system.[133] Such legislation, however, would cover only the roughly 12% of the incarcerated population in federal custody. Exercising federal jurisdiction over state and local facilities requires either federal dollars or the exercise of federal oversight (monitorship or receivership) pursuant to a legal agreement.

A carrot-and-stick approach would combine these two points of leverage. Congress could charge the Department of Justice with identifying prisons with elevated levels of violence, including but not limited to homicide or drug overdose. It could set aside substantial funds—the aforementioned $500 million—in remediation grants, to be disbursed by DOJ to problematic facilities. Receipt of these grants, however, should be contingent on several factors. Recipients should be obliged to share comprehensive data on all aspects of prison life and administration and routinely report improvements in key metrics, including deaths and violence. Recipients which fail to do so may be subject to more stringent measures, up to and including federal receivership.

Such interventions can improve the quality of life in American prisons and jails, guaranteeing the basic good of safety to all, but they may also reduce crime generally. Evidence from Colombian prison construction suggests that prisoners quasi-randomly assigned to newer (and generally better) prisons were up to 36% less likely to recidivate. While the applicability of this finding to the U.S. is limited, and its mechanisms ambiguous, it suggests that improving prison conditions may benefit society in the long run, too.[134]

One standard channel for prison improving crime outcomes is rehabilitation, interventions that reduce people’s individual tendencies to commit crime by changing their attitude, skills, personality, etc. Effective rehabilitative interventions would dramatically improve the cost/ benefit ratio for incarceration, yet such interventions have long been an elusive goal.[135] Since Greg Martinson’s landmark 1974 Public Interest essay “What Works?” researchers have struggled over whether rehabilitative programs serve their intended goals, or if such goals can actually be achieved.[136] Research evidence suggests that the effectiveness of rehabilitative programming has been small to non-existent. Remedial education programming, drug treatment, and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) reduce recidivism rates around 10 percentage points in the highest quality studies, while vocational training, religious interventions, and psychological treatment are less well-supported. And there is a great deal of heterogeneity within categories of programming—some CBT interventions work, some do not, and which works best remains an open question.[137]

There are reasons to be skeptical of the efficacy of rehabilitative programming, particularly in the prison context. Many people in prison are indefatigable offenders; as Manhattan Institute scholar Heather Mac Donald once put it, prison is “a lifetime achievement award for persistence in criminal offending.”[138] A sample of prisoners released in 34 states in 2012 had a median eight arrests and four prior convictions—most prisoners have a lengthy rap sheet.[139] This persistent offending may reflect hard-to-alter tendencies: 40% to 70% of American prisoners have anti-social personality disorder.[140] In addition, most offenders are male, and a well-established principle in social policy interventions is that they tend to benefit women far more easily and consistently than men.[141]

But, as discussed above, we can’t truly say whether rehabilitation works or not. Much of the evidence simply isn’t there. Rather than give up altogether on rehabilitation, therefore, more time and money could be put into investigating whether rehabilitation really is possible.

The federal government is well-positioned to facilitate this investigation. As of early December 2022, BOP facilities were home to nearly 145,000 people, the nation’s largest prison system.[142] This is a prime population with whom randomized evaluations of rehabilitative programs can be carried out. Doing so simply means randomizing in some way who is given access to the always limited supply of rehabilitative programming, then comparing behavior, recidivism rates, and other indicators within the treated and untreated group. Such studies could facilitate not only the general assessment of types of programs but allow a better exploration of which programs work well, and for which types of offenders. In addition, such research would allow the DOJ to actually comply with the mandates of the FIRST STEP Act of 2018, which required the allocation of early release credits on the basis of enrollment in evidence-based recidivism reduction programs; as Byrne notes, there are few such programs at present.[143]

Congress could therefore newly charge the National Institute of Justice and Office of Justice Programs with disbursing funding for research into corrections and evaluating that research. OJP and NIJ can already do as much under the 1994 Violent Crime bill,[144] but Congress could consolidate and expand funding in this area, including by moving the National Institute of Corrections under OJP’s umbrella (in line with DOJ’s FY 2020 budget request) and fully funding NIJ (as discussed above).[145] Funds would specifically be designated for corrections researchers and go to researchers proposing high-quality (i.e., randomized controlled trials) studies that include three years or more of follow-up and provide evidence on a variety of indicators of rehabilitation.

Improve Crime Data

Data is the lifeblood of a modern criminal justice system. Without high-quality data, it is impossible to assess the impact of policies and practices on crime and other indicators of community well-being. Data permits the targeting of enforcement, focusing on the people and places who drive crime, while leaving law-abiding citizens alone. And it lets policymakers, from mayors to the president, make better-informed decisions about keeping Americans safe.

Yet as discussed above, our crime data do not serve these purposes. They are misleading, poorly organized, and behind the times. A 21st-century criminal justice system requires 21st-century data. Consequently, Congress should take two steps to improve reporting: link NIBRS compliance to continued receipt of federal public safety funds and establish a national “sentinel city” program to report crime data in near-real time.

The first step is relatively straightforward. First, permit jurisdictions to spend any DOJ grant they have received or will receive on NIBRS-related upgrades, training, and other transition costs. Second, reduce by a fixed percentage the amount of funding individual jurisdictions can receive through DOJ programming if they are not compliant with NIBRS, with that percentage increasing every year until compliance is met. Jurisdictions still not in compliance with NIBRS reporting standards in 2023, for example, would see a 5% funding cut; by 2024, a 10% cut. The maximum percentage should be short of 100% and may need to exempt certain vital programs, but it should still be substantial enough to act as an effective incentive.

Some departments may insist this approach is extreme. It may make sense to exempt some jurisdictions, particularly small ones—those with populations below 50,000, for example—for which compliance costs are more burdensome and for which federal dollars are more important. In essence, though, this approach offers both a carrot—free reign to spend almost any DOJ funds on NIBRS updates—and a stick—loss of funding if departments don’t. Such funding clawbacks have been used, for example, to induce state complicity with the federal drinking age of 21, to great success, and it is worth emphasizing that departments have had decades to switch to NIBRS and eight years’ forewarning of the transition: it is not as though this is a sudden surprise.

Full adoption of NIBRS, though, would still leave the country with imperfect knowledge of crime, and with a dramatic lag time. There is no particular reason this should be. Police departments record arrests, complaints, stops, and other events of interest in real time, and many jurisdictions, big and small, release these data quarterly, monthly, weekly, or even daily. For certain variables of interest—especially homicides and shootings—near-real-time data collection is simply a matter of political will.

Consequently, in addition to pushing for universal NIBRS adoption, policymakers could consider establishing a crime sentinel cities program.[146] Participating cities, ideally 100 or so, would receive funding to report data on crimes of interest using a standard data format and definitions, made available through an open data portal, at a regular and frequent interval. Such a program could start with the most salient crimes—homicides and shootings—and scale up with time. This would, at the very least, bring crime reporting in line with the level of death reporting that the CDC has been able to produce for decades in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Because many large cities already report data in this way, the program should be relatively cheap to implement. As crime analysts Jeff Asher and Rob Arthur have shown, the level of homicide in a sample collection of major cities is generally a good index of homicide nationwide.[147] That means that with just a sample of jurisdictions, policymakers could have detailed, near-real-time measures of the direction of crime in the entire nation.

Conclusion: A 21st-Century Criminal Justice System

America is in the midst of an unprecedented spike in murder. While homicide rates remain lower, in absolute terms, than the peaks of the 1980s and 1990s, the dramatic increase over the past three years augurs ill for future trends. Policymakers can cross their fingers and hope the problem will go away, but voters are noticing. It is better, then, to take this moment to acknowledge that the American criminal justice system has been underproviding safety for years; that that under-provision is driven largely by the inadequacies in our out-of-date criminal justice system; and that we can commit to making a serious upgrade.

Doing so will not be cheap, but the program laid out above is a drop in the bucket of federal criminal justice spending, never mind of federal spending in general. And aggressive federal action in response to crime is far from unprecedented. Absent this action, the problem may abate on its own, but even then, we will be left with a criminal justice system less effective and efficient than the American people—particularly the tens of thousands of Americans victimized by crime every year—deserve.

About the Author

Charles Fain Lehman is a fellow at the Manhattan Institute, working primarily on the Policing and Public Safety Initiative, and a contributing editor of City Journal. He also hosts the podcast Institutionalized with cohost Aaron Sibarium. Lehman was previously a staff writer with the Washington Free Beacon, where he covered domestic policy from a data-driven perspective. His work on criminal justice, immigration, and social issues has appeared in the Wall Street Journal, National Review Online, and Tablet, among other publications, and he is a contributing writer with the Institute for Family Studies. Originally from Pittsburgh, he now lives in the Maryland suburbs of Washington, D.C.

Endnotes

Photo by MattGush/iStock

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).