In the last few years, buttressed by Ta-Nehisi Coates’ writings and the New York Times 1619 Project, the idea that structural racism permeates every aspect of society and the economy has been mainstreamed. Proponents of this narrative argued that the pre-pandemic increase in black employment was not all good news because it camouflaged a deepening racial divide.

One indicator that racial discrimination increased over the last four decades is that average hourly wage growth of black men and women lagged behind the wage growth of non-Hispanic white men and women. In an influential Economic Policy Institute paper, Valerie Wilson and William Rodgers found a 9 percentage point decline in the relative earnings of black men and a 14 percentage point decline among black women between 1979 and 2015. The widening disparity suggests that the civil rights movement did not crystallize its gains from the 1960s and structural racism resulted in lower earnings. But using a different earnings measure – median annual earnings of full-time/full-year workers (FTFY) – and adjusting for intensity of labor force attachment over a 15-year period – leads us to a more nuanced assessment that can help us understand what factors are driving the earnings gap.

If we limit the analysis to FTFY workers, the relative annual median earnings of black male workers remained constant, though, even among FTFY workers, black women’s wages fell relative to white women’s. Trends are dramatically different if we compare black and white workers with the same level of work intensity.

Even among FTFY workers in a given year, those with irregular employment histories are likely to have lower earnings. To assess earnings differentials over many years, we used data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) on workers over three different 15-year cohorts: 1967–1981, 1982–1996, and 2002–2016.

These 15-year cohorts enable us to distinguish the level of work intensity. Rose and Heidi Hartmann showed that even a single year out of the labor force is associated with low average earnings in the years in which they were working. To simplify presentation, three levels of labor force attachment are created:

- Strong: those who had positive income every year and were FTFY in at least 12.

- Medium: those who had positive earnings every year but were FTFY in fewer than 12.

- Weak: those who didn’t have positive income in all 15 years.

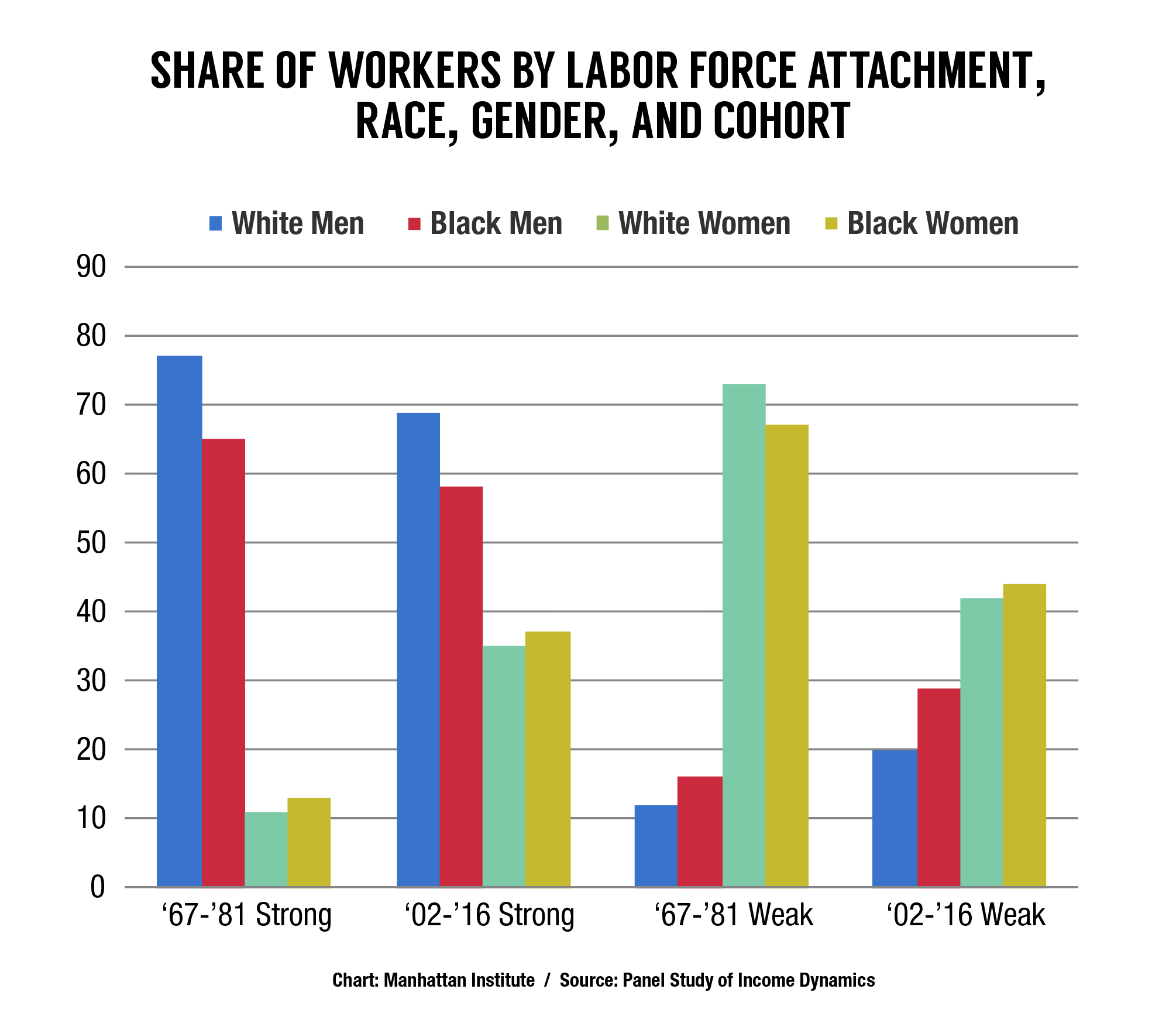

Figure 1 compares the first and most recent 15-year periods. The labor force attachment weakened for all men. While the share of white men with strong attachment declined slightly more than for black men, the share with weak attachment increased much more among black men. By contrast, women’s labor force attachment increased. Among white and black women, the share of strong attachment increased by the same percentage points, but the share of weakly attached workers declined by much more among white than black women. Thus, for both genders, black workers became relatively more concentrated among those with weak labor force attachment than white workers.

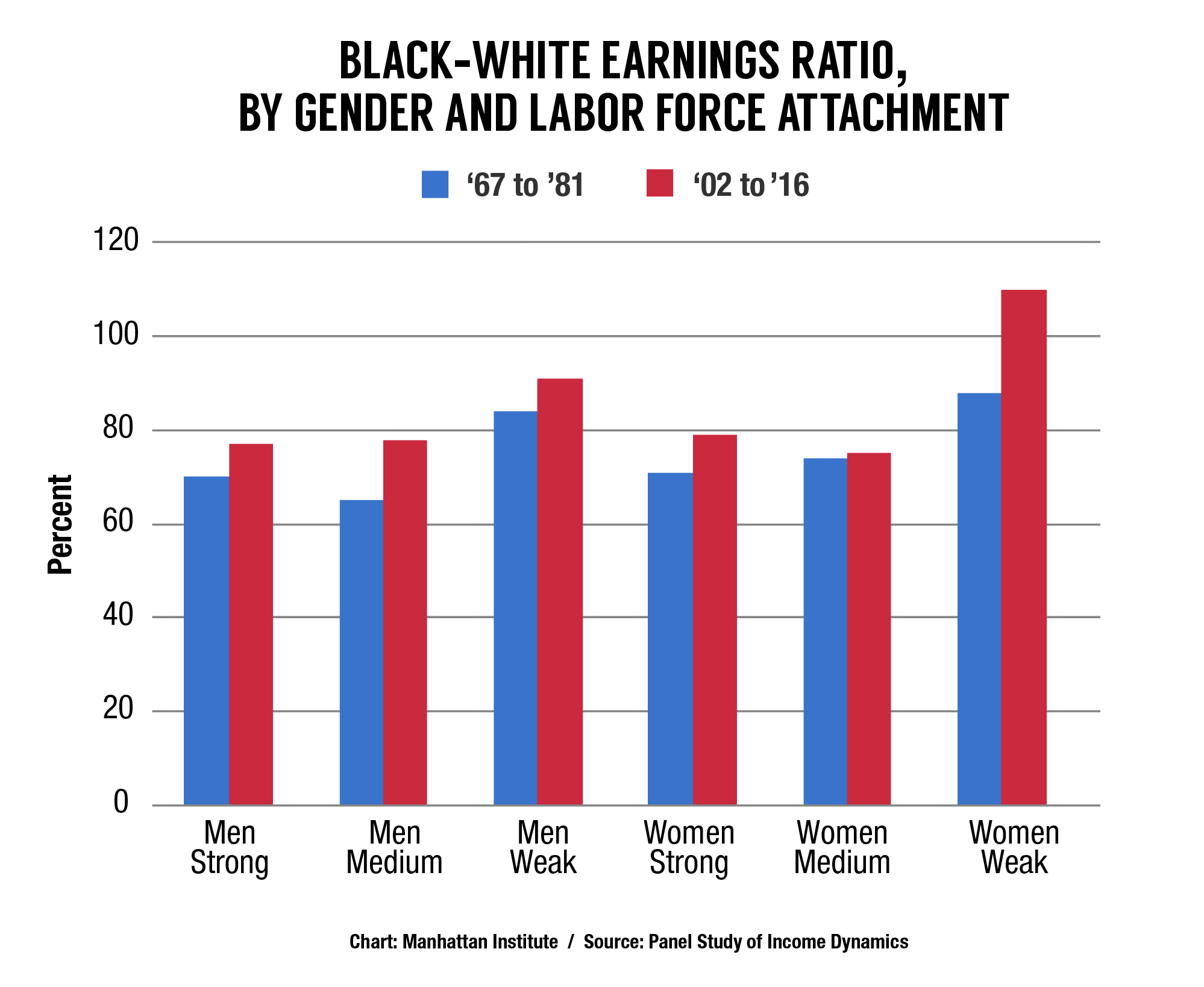

Labor force attachment tends to influence earnings, so controlling for it sheds new light on the gap. The earnings gap among men narrowed within each attachment category (figure 2). For example, the earnings of black men (with strong attachment) relative to strongly attached white men increased by 7 percentage points, rising from 70 percent in the first period to 77 percent in the most recent period. The gains within the stronger attachment categories, however, were not sufficient to offset the relative growth of black men with weak labor force attachment, so that the overall earnings ratio was unchanged.

Black/white earnings gaps among women also narrowed for the same levels of attachment. However, the overall earnings gap actually rose for two reasons: first, fewer white women are now in the weak attachment category; second, women with weak attachment have very low annual earnings.

These findings show the importance of labor market experiences over many years. In particular, narrowing the gap requires understanding what is driving differences in attachment and why black men have become less likely to have persistent full-time work.

Robert Cherry is the Stern Professor at Brooklyn College and the CUNY Graduate Center. Stephen Rose is a nonresident fellow in the Income and Benefits Policy Center at the Urban Institute.

Interested in real economic insights? Want to stay ahead of the competition? Each weekday morning, e21 delivers a short email that includes e21 exclusive commentaries and the latest market news and updates from Washington. Sign up for the e21 Morning eBrief.

Photo by Justin Sullivan/Getty Images