Why “Percent Plans” for University Admissions Aren’t a Colorblind Success

Introduction

In her 2024 State of the State address, New York Governor Kathy Hochul introduced the Top 10% Promise, a policy offering New York students ranked in the top 10% of their high school class direct admission to the State University of New York (SUNY) system. “Access to higher education,” she said, “has the potential to transform the lives of young New Yorkers and change the trajectory of a student’s life. Through these bold initiatives, we are taking critical steps toward ensuring every New York student can continue their education, build their professional career, and pursue their dreams.”[1] This policy is now in effect.

Hochul’s initiative comes on the heels of the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2023 strike-down of affirmative action in Students for Fair Admissions v. President and Fellows of Harvard College (SFFA). “Percent plans”—admissions policies that grant a certain percentage of each high school’s senior class direct admission to a state university system on the basis of high school GPA—are nothing new. Texas, California, and Florida all implemented some version of a percent plan for admission to their public university systems in the wake of state affirmative action bans, beginning in the late 1990s. Because these policies offer a top certain percent of each high school’s graduating class access to a state’s university system, they have been considered by both Democrats and Republicans to be merit-based and race-neutral alternatives to racial preferences.

This brief considers the legislative history, mechanics, and efficacy of the nation’s three original percent plans, focusing particularly on Texas’s top 10% law. I examine the consequences of the Lone Star State’s percent plan for racial and geographic diversity and academic performance at the University of Texas at Austin (UT) and Texas Agricultural and Mechanical University (Texas A&M).

This brief finds:

- Texas’s top 10% law did increase black and Hispanic enrollment at the state flagships, but it did not fully restore black and Hispanic enrollment lost at these campuses following Hopwood v. Texas,[2] a 1996 Fifth Circuit decision that banned affirmative action in the state. Similarly, while the percent plan did increase access to UT and Texas A&M among disadvantaged high schoolers, the extent of this increase is contested in social science research.

- The consequences of Texas’s percent plan for academic performance at UT and Texas A&M are mixed. Top 10% enrollees do not seem to outperform non–top 10% enrollees by leaps and bounds, as has often been assumed. However, top 10% enrollees do not lag behind, either. Descriptive data shared by UT’s admissions office show that while top 10% enrollees initially had higher freshman-year GPAs, on average, than non–top 10% enrollees, their performances converged after a few years. And while top 10% enrollees at first possessed higher SAT scores than non–top 10% enrollees, this eventually flipped.

- Percent plans that are concerned primarily with bolstering black and Hispanic enrollment at selective public universities and do not include standardized testing requirements are not significantly different in practice from affirmative action. Both Democrats and Republicans who choose to implement percent plans for their respective state university systems should remain cognizant of this reality, especially given the change in presidential administration.

- On his second day in office, President Donald Trump issued an executive order that called on the Department of Justice and the Department of Education to jointly enforce the Supreme Court’s ban on affirmative action in university admissions.[3] Shortly thereafter, the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights shared guidance with universities on how to comply with the decision. The Trump administration made clear that the use of both racial preferences and policies that, while race-neutral on their face, are race-conscious in aim and effect are prohibited.

- Relying on non-racial information as a proxy for race, and making decisions based on that information, violates the law. That is true whether the proxies are used to grant preferences on an individual basis or a systematic one. It would, for instance, be unlawful for an educational institution to eliminate standardized testing to achieve a desired racial balance or to increase racial diversity.[4]

- This statement calls into question the legality of percent plans that do not take students’ standardized test scores into account and are aimed, even in part, at increasing black and Hispanic enrollment.

- The goal of such a policy—and university admissions more broadly—should be furthering equal opportunity and student success, which requires the inclusion of SAT/ACT scores in the application process and a commitment toward colorblindness.

A Brief History of Percent Plans in Undergraduate Admissions

Texas

In 1997, the 75th Texas legislature passed House Bill (H.B.) 588: the top 10% law. H.B. 588 guaranteed Texas students ranked in the top 10% of their high school class direct admission to any of the state’s four-year public colleges or universities.[5] By rewarding merit and increasing college access, this law was touted as a race-neutral alternative to affirmative action, which was overturned in the 1996 ruling in Hopwood v. Texas. That case barred public colleges and universities in Texas from considering applicants’ race and ethnicity in the admissions process.[6] H.B. 588 was spearheaded by the late Democratic Congresswoman Irma Rangel, the first Mexican American woman elected to serve in the Texas House of Representatives, and signed into law by then-Governor George W. Bush.[7]

However, Texas’s top 10% law was not exactly race-neutral.[8] H.B. 588’s legislative history reveals that a primary purpose was to recover the black and Hispanic enrollment lost at the state’s two flagships—UT and Texas A&M—as a result of Hopwood.[9] Because the law granted the top decile of graduates in each high school automatic admission to the state’s university system, it utilized existing segregation among high schools in Texas to increase the number of black and Hispanic students at the flagships, where white and Asian American students combined made (and still make) up more than 50% of the students.[10]

Under H.B. 588, class rank was calculated by the district or school from which each applicant was expected to graduate, using coursework completed at the end of 11th grade, the middle of 12th grade, or high school graduation (whichever was most recent at the time of application). The law also required applicants to complete courses designated as “minimum graduation criteria,” to submit SAT or ACT scores (although these scores were not considered in the admissions process), and to pass the state’s reading, writing, and math Texas Academic Skills Program. Additionally, students who chose to attend UT or Texas A&M through the top 10% law were not guaranteed the major of their choice.[11]

In 2009, Texas lawmakers modified the top 10% law under Senate Bill (S.B.) 175.[12] Most notably, S.B. 175 placed a cap on how many first-year, in-state applicants could gain admission to UT, Texas’s most selective public university, through the percent plan: 75% of each incoming class. This meant that after the law took effect, the class rank needed to secure a seat at UT through the percent plan could vary from one admissions cycle to the next (as opposed to holding steady at 10%), depending on the number of applications the institution received.[13] For the fall 2024 admissions cycle, graduates will likely have had to be in the top 6% of their class to gain admission to UT.[14]

The reasoning behind S.B. 175 was twofold. First, administrators at UT “warned at the time that they soon wouldn’t be able to accept anyone outside the top 10 percent, making it hard to field a football team or attract any out-of-state students.” Second, “[s]uburban legislators were also upset because the law made it nearly impossible for quality students from their competitive schools to get into UT-Austin if they weren’t in the top 10 percent.” These concerns were not unfounded; by 2008, 81% of incoming freshmen at UT were admitted under the top 10% law. In other words, out-of-state applicants and applicants ranked outside the top decile of their graduating class were, effectively, crowded out of the elite university, regardless of the competitiveness of their high school, standardized test scores, extracurricular accomplishments, or other accolades. Then–president of UT Bill Powers informed the Texas legislature in 2009: “It has become a crisis for us. We’re simply running out of space.”[15]

S.B. 175 addressed Powers’s and others’ concerns by reserving 25% of seats in each freshman class at UT for those who applied under regular (non–top 10%) admissions. That said, S.B. 175 had the same primary goal as H.B. 588: bolstering black and Hispanic enrollment at the elite university. The law thereby required UT administrators to track the university’s progress in “recruiting students who are members of underrepresented demographic segments of the state’s population” and to report these results to the governor, lieutenant governor, and speaker of the Texas House of Representatives each year.[16]

Last, S.B. 175 required top 10% applicants to complete the Distinguished Level of Achievement higher-performance category as a high school student, under the Foundation, Recommended, or Advanced High School Program, as defined in the Texas Education Code, at a public high school or the equivalent in content and rigor at a private high school. This was to ensure that the top 10% students had the academic preparation necessary to succeed at Texas universities, particularly the more rigorous flagships. If an applicant was unable to complete the program, S.B. 175 allowed the student to demonstrate college readiness by earning the requisite scores on the ACT or SAT.[17] State Representative Florence Shapiro, a Republican, was the primary author of S.B. 175; then-Governor Rick Perry signed the bill into law in June 2009.[18]

California

In 1996, the same year that Hopwood was decided, 55% of California voters approved Proposition 209, which amended the state constitution to prohibit racial preferences (i.e., affirmative action) in the public sector, including in public college and university admissions. Proposition 209 took effect in 1998.[19]

In 1999, three years after Proposition 209 passed, then-Governor Gray Davis proposed, in his inaugural address, that California students ranked in the top 4% of their high school class should gain direct admission to the University of California (UC) system. “We will seek to ensure diversity and fair play,” Davis stated, “by guaranteeing to those students who truly excel by graduating in the top four percent of their high school—whether it’s in West Los Angeles or East Palo Alto—those kids who excel will automatically be admitted to the University of California.”[20]

Shortly thereafter, the UC Board of Regents voted 13 to 1 to implement Davis’s percent plan, Eligibility in Local Context (ELC). ELC guaranteed California students ranked in the top 4% of their graduating class direct admission to the UC system but not necessarily to the campus of their choice. Critics at the time pointed out that admission to the UC system, particularly the flagship institutions, was more competitive than admission to Texas schools, so a percent plan would have the likely effect of lowering the academic quality of students automatically admitted. As Ward Connerly, the University of California Regent and mastermind behind Proposition 209, said, “If you admit the top 4 percent at every high school, while that sounds good politically, the effect is that … without a doubt it does amount to a relaxing of statewide standards.”

But for progressives, supporters of affirmative action, and supporters of Davis’s ELC, one of the goals was to increase the number of black and Hispanic students in the UC system following Proposition 209, particularly at the system’s most elite campuses—UC Berkeley and UCLA—so the percent plan went into effect.[21]

To be eligible for admission to the UC system through ELC at the time, students had to complete 15 units of the system’s high school course requirements (A–G courses) and maintain a minimum GPA of 2.8. When applying for ELC admission during their senior year, students had to submit their SAT I or ACT scores and take three SAT II subject tests. While an ELC applicant’s performance on these standardized tests was not considered in the application process to the UC system at large, such performance was considered by each individual UC campus when making admissions decisions.[22]

The UC system’s percent plan has since changed. Today, California offers in-state applicants two pathways for gaining automatic admission to the UC system. The first pathway is ELC, in which students ranked in the top 9% (as opposed to the top 4%) of their graduating class are admitted to the UC system. To qualify for ELC, an applicant must, as before, complete 15 units of A–G coursework in total (11 units by the end of junior year) and maintain a minimum 3.0 GPA (up from 2.8). If an applicant’s A–G GPA meets or exceeds the benchmark A–G GPA for the applicant’s high school, then the applicant will be designated as ELC in applications to the UC campuses.[23]

The second pathway, known as the statewide guarantee, offers students ranked in the top 9% of all California graduates direct admission to the UC system. UC administrators determine the top 9% of California seniors with a formula called the statewide index. The statewide index first considers the number of A–G courses a student has taken, is taking, or plans to take. UC administrators then calculate a student’s “UC GPA” using the A–G courses that the student has completed between the end of 9th grade and the end of 11th grade. If a student’s total number of A–G courses is equal to or greater than the number of A–G courses listed in the statewide index for the student’s GPA, then that student ranks in the top 9% of California graduates.[24]

Since 2021, UC has been “test-blind.” Unlike Texas, where top 10% applicants must still submit their SAT or ACT scores, neither the UC system at large nor any individual UC campus requires these scores (the same holds true for both in-state and out-of-state applicants under regular admissions). Rather, once a California student has been deemed eligible for ELC or statewide guarantee, each UC campus considers 13 factors, in addition to GPA, when determining whether to admit the student. Several of these factors—such as the neighborhood in which a student lives and the quality (in terms of academic rigor and availability of educational resources) of a student’s high school—have been criticized by some opponents of race-conscious admissions as racial proxies.[25]

Finally, it is worth noting that while ELC and statewide guarantee are supposed to provide eligible California students with admission to the UC system, UC’s website indicates that there may not always be enough space in the system to accommodate every such student.[26]

Florida

When Connerly set his sights on outlawing racial preferences in Florida through a ballot measure similar to what he had championed in California, then-Governor Jeb Bush decided to beat him to the punch. In November 1999, Bush signed Executive Order 99-281, referred to as the One Florida Initiative. The executive order eliminated the use of race and gender preferences in the state’s public sector, including in public college and university admissions. However, race consciousness was still permissible in awarding scholarships, conducting outreach, and developing pre-college summer programs.[27]

Having taken a page out of his brother’s playbook in Texas, Bush replaced racial preferences in his state’s public college and university admissions with a percent plan. Called the Talented Twenty (TT) program, the plan guaranteed students who finished in the top 20% of their graduating class automatic admission to Florida’s university system at large but not to the campus of their choice. A primary goal[28] of the TT program was to increase black and Hispanic enrollment at the system’s most elite campuses—the University of Florida (UF) and Florida State University (FSU)—after the executive order took effect.[29]

To be eligible for admission to Florida’s university system under the TT program, an applicant must meet four requirements: be enrolled in a Florida public school and graduate with a standard diploma; rank in the top 20% of the class after seventh-semester grades have posted; submit SAT, ACT, or CLT scores (although these scores are not considered in the admissions process); and complete the state university system’s high school course requirements as outlined in the Board of Governors Regulation 6.002.[30]

Over the years, Bush has maintained that his TT program has been a success. For example, when campaigning for the 2016 Republican presidential nomination, he touted the policy as a win for conservatives and for anyone who believes in colorblindness and meritocracy.[31]

The Consequences of Texas’s Top 10% Law

Racial Diversity

Texas’s, California’s, and Florida’s percent plans were implemented in part toward increasing the number of black and Hispanic students at each state’s most selective public universities (UT, Texas A&M, UC Berkeley, UCLA, UF, and FSU) in the wake of state affirmative action bans. As a result, both the social science literature and reporting on these admissions policies have focused largely on whether they are an effective substitute for racial preferences when it comes to fostering racial and ethnic diversity in higher education. How percent plan enrollees fare academically compared to their regular-admissions counterparts—e.g., in terms of freshman-year performance or four-year graduation rate—appears to have been of a lesser concern to social scientists and journalists alike.

The most widely studied of the nation’s percent plans are H.B. 588 and S.B. 175 in Texas. Media reports have praised these laws as successful implicit race-conscious alternatives to explicit race-conscious admissions. In 1999, just two years after H.B. 588 was passed, the New York Times published an article about the policy’s effect on student-body diversity at UT, concluding decisively: “[T]he racial mix on this campus has been restored to what it was under affirmative action, and the university has also been able to attract students … from impoverished rural and inner-city schools that rarely sent graduates here before.”[32]

The social science research on whether Texas’s top 10% law restored black and Hispanic enrollment at the state flagships to pre-Hopwood levels is, however, less decisive. On one hand, several studies have shown that this policy does not lead to the same level of black and Hispanic representation at UT or Texas A&M as under racial preferences, particularly when accounting for demographic change in the state’s high school population.

For example, in a well-cited 2010 study, sociologists Angel Harris and Marta Tienda found—using data on public high school graduates from the Texas Education Agency and administrative data on applicants, admittees, and enrollees at UT and Texas A&M—that the top 10% law failed to “restore diversification” at these universities.[33] Table 1 displays the specific findings with regard to the changing racial and ethnic makeup of enrollees at both flagships from 1990 to 2003. This time frame includes three admissions regimes: affirmative action pre-Hopwood (1990–96), neither affirmative action nor H.B. 588 (1997), and H.B. 588 (1998–2003).

Table 1 displays the “yield rate”—the percentage of admittees who enrolled at each flagship—for each racial and ethnic group at UT and Texas A&M. (Because the concern here is whether Texas’s percent plan restored racial and ethnic diversity at the flagships to pre-Hopwood levels, the number of black and Hispanic students who were admitted and enrolled at these schools—i.e., the yield rate—is more relevant than the number of students who were admitted overall.) At UT, the yield rates for white, Asian, and Hispanic students rose under the “no policy” period (compared to under racial preferences), while the yield rate for black students declined. In shifting from the “no policy” period to the period governed by the top 10% law, white, Asian American, and Hispanic yield rates at this flagship declined, while the black yield rate increased. At Texas A&M, all racial and ethnic groups saw a decline in yield rate following Hopwood and an increase in yield rate following the enactment of the top 10% law.[34]

Harris and Tienda also found that the yield rates for black and Hispanic students at Texas A&M, and for Hispanic students at UT, were higher under the top 10% law than under a regime of outright racial preferences. That said, these yield rates, they noted, were based on small samples of black and Hispanic enrollees compared to whites. The black and Hispanic group shares of total enrollees at UT and Texas A&M (Table 2) were smaller under the top 10% law than they were pre-Hopwood, suggesting that pre-Hopwood levels of racial and ethnic diversity had not been restored.[35]

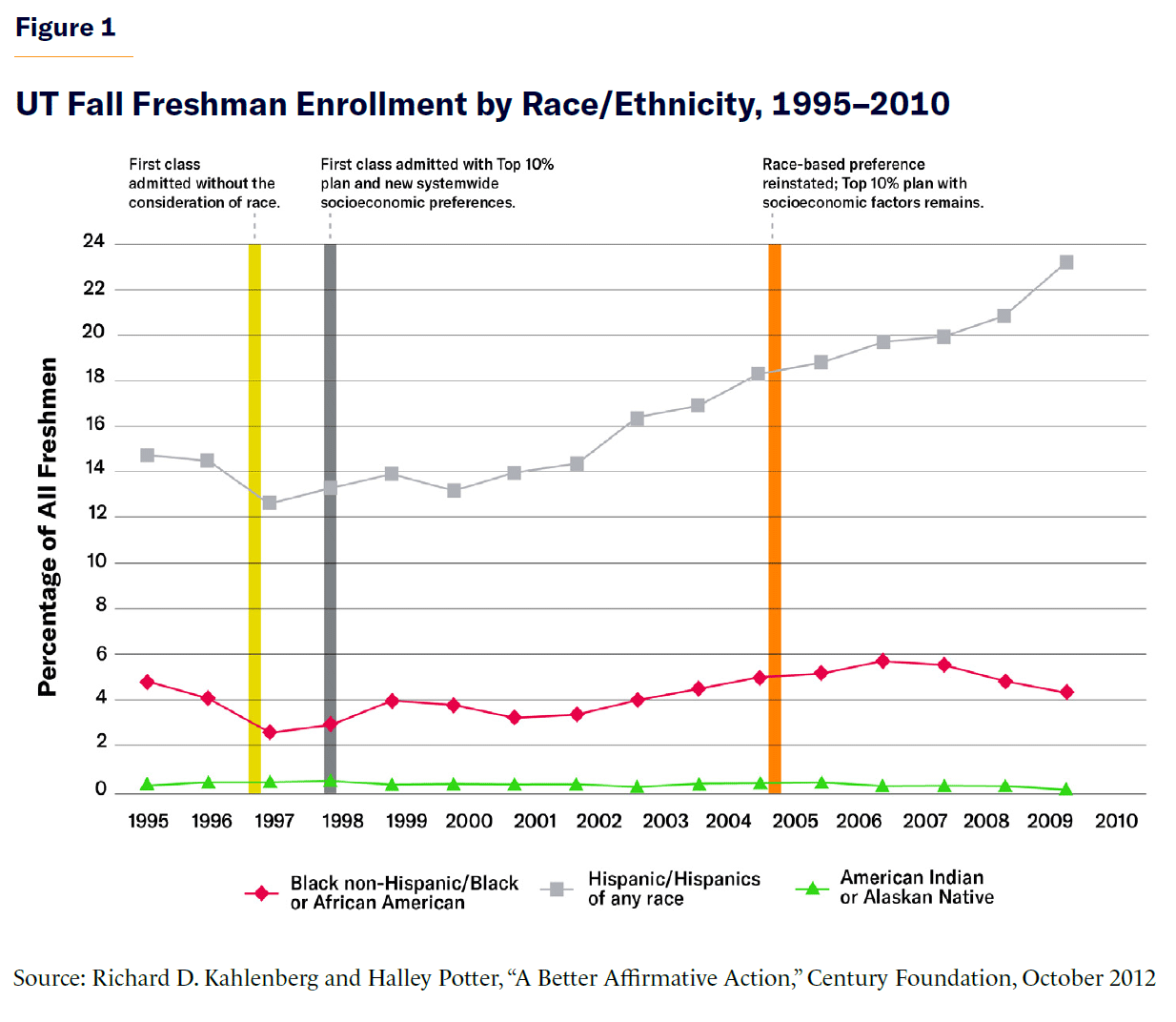

On the other hand, Richard Kahlenberg and Halley Potter, in a 2012 report for the Century Foundation, claimed that Texas’s top 10% law had, for the most part, restored black and Hispanic enrollment at UT and Hispanic enrollment at Texas A&M to pre-Hopwood levels. Using data from the National Center for Education Statistics on fall enrollment at both flagships from 1995 to 2010 (Figures 1 and 2), Kahlenberg and Potter found, for example, that in 2004 (the last year before racial preferences were reinstated at UT for students who applied outside the percent plan), the combined black and Hispanic shares of UT freshmen was higher (21.4%) under the top 10% law than in 1996 (18.6%) under affirmative action.[36]

Some advocates of racial preferences criticize Kahlenberg and Potter’s findings, because the rise in diversity at UT and Texas A&M following the top 10% law “failed to keep up with even faster statewide growth in diversity,” as the report acknowledges.[37] (Put another way, it is somewhat imprecise to compare the shares of black and Hispanic freshmen at the flagships pre-Hopwood to those shares under Texas’s percent plan without accounting for demographic change in the state’s population of high school graduates.) Kahlenberg and Potter respond to this criticism by noting that “while reference to the gap between black and Latino representation at the University of Texas as compared with statewide numbers is a valid public policy concern, as a legal matter, it has never been accepted by the U.S. Supreme Court.”[38]

High School Diversity

Another goal of Texas’s top 10% law, particularly of legislators representing rural (and typically red) areas of the state, was to diversify the pool of high schools that regularly sent students to these elite universities. Only a handful of public high schools in Texas sent graduates to UT and Texas A&M every year, and these schools were high-resource, high-achieving, and often located in suburban areas. By contrast, schools that rarely or never sent graduates to the flagships had the highest percentage of free lunch–eligible students, the smallest 12th-grade enrollment, and the lowest SAT scores and were the farthest in distance from each campus.[39]

In a 2022 paper, economists Daniel Klasik and Kalena Cortes analyzed 2 years of pre–top 10% law data and 18 years of post–top 10% law data to determine whether Texas’s percent plan did, in fact, make high schools that rarely or never sent students to UT and Texas A&M prior to 1998 more inclined to do so. Their results were mixed.

Klasik and Cortes classified the high schools in their data as “always-senders,”“occasional-senders,” and “never-senders.” High schools that were always-senders sent students to either flagship during both of the pre–top 10% policy years observed; occasional-sending high schools sent students to either flagship during one of the pre-policy years observed; and never-sending high schools sent no students to either flagship during either pre-policy year.[40]

In the first five years after the top 10% law went into effect, always-senders were 11 percentage points less likely to send students to a flagship campus, while never-senders were 21 percentage points more likely and occasional-senders were 20 percentage points more likely. However, a 20-percentage-point increase in the likelihood of a high school sending a student to a flagship campus translated, Klasik and Cortes found, to a high school sending at least one more student to a flagship campus once every five years. “At this frequency,” they noted, “a student could graduate from a never-sending high school after the Top 10% Plan began having never seen a student enroll at a flagship campus during their entire four-year high school career.”[41]

Moreover, never-sending and occasional-sending high schools that did change their sending patterns after 1998 did not necessarily send that many more students to the flagships. The percentage of seniors from always-senders who attended UT or Texas A&M dropped by 0.6 percentage points, while the percentage of seniors from never-senders who attended either university increased by only 1.2 percentage points in the first 5 years of the law and only 1.7 percentage points in the entire 18-year period. Similarly, the percentage of seniors from occasional-senders who attended either of the flagships increased by 1 percentage point after five years and 1.3 percentage points in the long run.[42]

In terms of characteristics, schools with a higher proportion of black students, schools with more students overall, and schools farther from the flagships were more likely to send students to UT and Texas A&M after the top 10% law was enacted. Yet these increases, Klasik and Cortes explained, were “nearly all relatively small in magnitude.” Additionally, high schools with a higher proportion of free lunch–eligible students were less likely to send students to the flagships after 1998. Klasik and Cortes concluded: “Thus, on balance, our analyses reveal that the purported high school representation benefits of the percent plan in Texas appear to be overstated and may not go as far as advocates might have hoped in terms of generating access to the flagship campuses for all high schools in the state.”[43]

Economists Sandra Black, Jeffrey Denning, and Jesse Rothstein found, more decisively, that Texas’s top 10% law led students ranked in the top decile at high schools that traditionally sent few students to UT more likely to enroll, while students ranked outside the top decile at feeder high schools were less likely to enroll. They referred to the first group of students as “pulled in” by the law and the second group as “pushed out.”[44]

Using individual-level high school, higher education, and workforce data on students who graduated high school between 1996 and 2002 from the Texas Education Research Center, Black et al. discovered that pulled-in students were 5.3 percentage points more likely to attend UT after the top 10% law, while pushed-out students were 3.7 percentage points less likely to attend UT. In keeping with previous research, they also found that pulled-in students came from high schools with lower average standardized test scores and a higher proportion of underrepresented minorities than the high schools that pushed-out students came from.[45]

The social science research suggests, then, that while Texas’s top 10% law did increase the number of black and Hispanic students at UT and Texas A&M, it did not restore black and Hispanic enrollment to pre-Hopwood levels. In a similar vein, the law did increase access among disadvantaged schools, but the magnitude of this increase remains contested.

Consequences for Student Performance at the Flagships

Another concern for Texas legislators and administrators at UT and Texas A&M has been how top 10% enrollees perform academically at both flagships. Many social scientists who have studied Texas’s top 10% law have opted to compare the academic performance of percent plan enrollees at UT and Texas A&M to that of the students these enrollees “displace,” namely graduates ranked outside the top decile at feeder schools. Indeed, a major criticism of the top 10% law is that it “unfairly privileges high-achieving students who attend underperforming schools at the expense of putatively better qualified graduates from competitive high schools who may not achieve top 10% rank,”[46] as some scholars describe.

This criticism is not without merit. As sociologists Sunny Niu and Marta Tienda acknowledged in a 2010 paper:[47]

There is some foundation for concerns about college readiness of some students qualified for the admissions guarantee. Race and ethnic achievement gaps based both on grades and on standardized test scores widen over academic careers and carry over to college. Prior research shows that high school grades, advanced placement (AP) course completion, and standardized test scores are key predictors of postsecondary academic performance, as reflected in collegiate grades, persistence, and graduation rates.

However, Niu and Tienda also noted there is some evidence that “students who graduate at the top of their high school classes generally perform well in college, even if they attend low-resource high schools, partly because of their strong motivation to excel.” Former UT President Larry Faulkner claimed in 2000 that “top 10 percent students at every level of the SAT earn grade point averages that exceed those of non-top 10 percent students having SAT scores that are 200 to 300 points higher.”[48]

Using data on Texas public high school students enrolled at UT between 1990 and 2003, Niu and Tienda examined the validity of Faulkner’s claim: Did black and Hispanic top 10% enrollees perform as well or better academically than enrollees outside the top decile, many of whom were admitted with higher SAT scores? Their results were mixed.

Niu and Tienda found that despite their lower SAT scores, top 10% black and Hispanic students at UT did perform as well or better than white students ranked at or below the third decile in terms of freshman-year GPA, four-year college GPA, and freshman-year withdrawal rate, albeit modestly. That said, Niu and Tienda admitted that their data did not extend beyond 2003, when H.B. 588 had only been in effect for a few years. Moreover, they noticed that beginning in 2002, the “academic performance of top 10% students and their lower ranked counterparts converged,” likely because that was when the size of UT’s freshman class shrunk. “Stated differently,” Niu and Tienda concluded,“as the admission squeeze took its toll on students ranked at or below the third decile, test scores assumed a major influence on those admitted.”[49]

Black et al. examined the academic performance of top 10% enrollees as well, though in the context of six-year graduation rate.[50] These students were 3.9 percentage points more likely to graduate with a bachelor’s degree from UT in six years and 3.7 percentage points more likely to graduate from any four-year college in the state, relative to the study’s control group (students unlikely to be admitted to UT before or after the top 10% law). Black et al. also noticed that top 10% enrollees had higher scores on the Texas high school exit exam than pushed-out students.

After H.B. 588 took effect, the admissions office at UT began publishing descriptive data on the demographic makeup of top 10% and non–top 10% enrollees each year. The data include the mean freshman-year GPAs for top 10% and non–top 10% enrollees between 1996 (the year of the Hopwood decision banning affirmative action) and 2008. Figures 3 and 4 plot the mean freshman-year GPAs of top 10% enrollees against the mean freshman-year GPAs of non–top 10% enrollees by racial group.[51]

Recall that 1996 was the last year in which UT used affirmative action in admissions; 1998 was the first year in which the top 10% law was in effect; and 2004 was the year in which UT reinstated affirmative action for non–top 10% admissions (following the Supreme Court’s decision in Grutter v. Bollinger). UT’s descriptive data show that in the first few years of Texas’s percent plan, white and Asian top 10% enrollees had higher SAT scores, on average, than white and Asian non–top 10% enrollees. Eventually, however, this trend reversed, with non–top 10% enrollees overtaking top 10% enrollees. Meanwhile, for the years observed (1998–2008), black and Hispanic non-top 10% enrollees appeared to have either higher SAT scores or similar SAT scores to black and Hispanic top 10% enrollees. Any claim that top 10% enrollees academically outperform non–top 10% enrollees by leaps and bounds is, then, exaggerated, at least for the first 10 years of the percent plan.

The UT data also report mean SAT scores by racial/ethnic group for Texas students entering the flagship between 1996 and 2008. Figures 5 and 6 plot the mean SAT scores of top 10% enrollees against the mean SAT scores of non–top 10% enrollees by racial group.

UT’s descriptive data show that in the first few years of Texas’s percent plan, top 10% enrollees had higher SAT scores, on average, than non–top 10% enrollees. Eventually, however, this trend reversed, with non–top 10% enrollees overtaking top 10% enrollees. This is likely because as UT narrowed the size of its freshman class, admission became much more competitive, both generally and for non–top 10% applicants in particular (who, per S.B. 175, can already make up no more than 25% of each incoming class). In other words, considering that standardized test scores are a factor in non–top 10% admissions and that competition for a non–top 10% seat is now fiercer, it is unsurprising that the SAT scores of non–top 10% applicants are rising; they are incentivized to have high test scores. Meanwhile, top 10% applicants, whose SAT/ACT scores are not considered in the admissions process at UT, do not face the same pressure.

These results are worth taking seriously, given that many, including former UT President Faulkner, justified Texas’s top 10% law on the grounds that top 10% admittees represented the best and brightest students. While this remains true to some extent, the fact that the mean freshman-year GPAs of top 10% and non–top 10% enrollees have converged and that non–top 10% enrollees now have higher mean SAT scores than their top 10% counterparts should give pause. On these academic measures, non–top 10% enrollees perform as well or better than top 10% enrollees, contrary to what many legislators and university administrators behind the law originally anticipated. However, data from the UT Office of Admissions do not extend beyond 2008. If the trend continues, the data suggest that from 2008 onward, non–top 10% students had overtaken and would continue to overtake top 10% students.

A Better Path for University Admissions?

Ever since the Supreme Court struck down race-conscious admissions in SFFA, Texas’s, California’s, and Florida’s percent plans have received newfound interest. Advocates of racial preferences, along with those interested in diversifying higher education socioeconomically and geographically, view this policy as a way to help underrepresented minorities, poor kids, and students in inner cities and rural areas gain greater access to higher education. As sociologist Jeremy Fiel has said, percent plans “leverage secondary school segregation and redistribute opportunities across high schools to mitigate racial inequality in college-going and diversify enrollments, especially at selective universities.” These plans “fit in a class of race-blind efforts to reduce racial inequality by redistributing opportunities across segregated spaces, rather than by desegregating spaces or allocating opportunities to classes of individuals.”[52]

Of course, percent plans are not really race-blind. The legislative histories of Texas’s, California’s, and Florida’s policies reveal that bolstering the number of black and Hispanic students at each state’s flagships in the absence of affirmative action is a key goal.

Despite this, the Supreme Court has expressed support for percent plans in the past. In a dissent in 2016’s Fisher v. the University of Texas at Austin, a case that concerned the constitutionality of UT’s use of racial preferences in non–top 10% admissions, Justice Samuel Alito, one of the Court’s most conservative members, described the state’s percent plan as a viable alternative to affirmative action for increasing racial and ethnic diversity in higher education.[53] Will the Court maintain a favorable view of percent plans and other supposedly race-neutral admissions policies going forward? That remains to be seen, given SFFA’s warning that “universities may not simply establish through application essays or other means the regime we hold unlawful today.” Legal challenges are already underway. In April 2024, the Boston Parent Coalition for Academic Excellence asked the justices to grant certiorari in a case involving an admissions policy that, while race-neutral on its face, was designed to discriminate against white and Asian American students—and succeeded in doing so.[54] Unfortunately, the Supreme Court denied the group’s petition.[55]

Democrats who believe that percent plans will function as a form of backdoor affirmative action post-SFFA will likely be disappointed. As this brief has shown, Texas’s top 10% law did increase the number of black and Hispanic students at the state flagships, but it did not restore black and Hispanic enrollment to pre-Hopwood levels. And while the law did increase access among disadvantaged high schools, the magnitude of the increase has been contested.

Percent plans have been supported by Republicans, too. This paper noted, for example, that two of the nation’s three percent plans were signed into law by Republican governors. These Republicans viewed the plans as race-neutral alternatives to affirmative action that were merit-based in theory. Political scientist Cyril Ghosh describes the position well:[56]

Of all these strategies, the Percent Plans are the most strongly in conformity with the ideology of the American Dream. They appear solidly meritocratic and avoid preferential treatment of any kind, whether they are racial preferences or legacies. These Percent Plans focus on merit but they also assess merit in terms of one’s accomplishments within a specific institutional setting and these accomplishments are measured with one’s peer group as a point of comparison. This practice is not only a more reasonable measure of how much effort a student has put into her work when controlling (roughly) for the resources she has been given, it also has the added advantage of circumventing the problem of cultural bias that is common in standardized tests.

Republicans in states that already have a percent plan for their public university system or are considering a percent plan in the wake of SFFA should acknowledge that if the intent behind the plan is to bolster black and Hispanic enrollment, then the plan is neither race-blind nor “solidly meritocratic.” Consider how Ghosh notes that an “added advantage” of percent plans, as currently practiced, is that they ignore applicants’ SAT/ACT scores, where there are longstanding racial disparities. If the goal of a percent plan is to increase the number of underrepresented minorities on a state’s flagship campus, then the absence of standardized testing requirements in the application process is, indeed, an added advantage. However, if the goal of a percent plan—and university admissions more broadly—is to promote equal opportunity and student success, then the exclusion of standardized tests is a detriment.

The SAT happens to be a better predictor of how a student will fare in college than the student’s high school GPA. In the last year, several highly selective colleges and universities have reinstated their standardized testing requirements for this reason. Dartmouth College, for example, noted in a January 2024 report that “test scores add significant value to the Admissions process at Dartmouth. They are significantly predictive of academic success at Dartmouth and increase the likelihood that Admissions will be positioned to identify high-achieving less-advantaged applicants. In particular, the data suggest that a test-optional policy leads large numbers of less advantaged applicants not to submit scores when it would benefit them to do so.”[57]

An admissions process concerned primarily with furthering equal opportunity and success for all students should be race-blind in aim and involve both grades and standardized test scores. Democrats and Republicans interested in implementing a percent plan for admission to their respective state university systems should keep this in mind and incorporate SAT/ACT scores to the greatest extent possible. Such a policy is not without precedent; before December 2020, the city of Boston accepted top-ranking students to its three selective public high schools on the sole basis of middle school grades and students’ scores on an entrance exam. Moreover, while Dartmouth found, in its aforementioned report on standardized tests, that a student’s SAT score was a better predictor of academic performance than high school grades, the strongest predictor was a combination of both measures.

Conclusion

After the Supreme Court green-lit the use of racial preferences in university admissions in 1978’s Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, the focus of this enterprise quickly became achieving racial parity. Decades later, in light of state affirmative action bans in Texas, California, and Florida, Democrats and Republicans alike turned to percent plans that base class rank on GPA alone as a policy that, while still geared toward diversity, is meritocratic in theory.

It is contested, however, whether percent plans in their current form do provide underrepresented minorities and disadvantaged students with greater access to the flagship campuses of state university systems. Moreover, while Texas’s top 10% law was justified, at least in part, on the grounds that top 10% enrollees would academically outperform their non–top 10% counterparts, UT’s own descriptive data between 1996 and 2008 suggest that this may no longer be the case.

The Court’s strike-down of affirmative action in SFFA provides Americans with the opportunity, after nearly a half century, to shift the focus of university admissions away from diversity and toward meritocracy, equal opportunity, and student success. Percent plans that are aimed at increasing the number of black and Hispanic students at states’ flagship campuses and thereby eschew standardized test scores are not much different from affirmative action. So, if a state’s legislature or other officials do decide to implement a percent plan for admission to the state’s university system, then this plan should be race-blind in aim and base a student’s class rank on both grades and SAT/ACT performance.

New York’s Top 10% Promise does take students’ standardized test scores into account. However, Governor Hochul has also emphasized that an important goal of the policy is to bolster enrollment of underrepresented minorities in the state university system.[58]

To be eligible to gain admission to one of SUNY’s nine participating campuses under the plan, a student must be on track to graduate high school with either an advanced Regents diploma or an International Baccalaureate (IB) diploma. Students who are on track to graduate with a Regents diploma and satisfy any of the following criteria are also eligible: SAT combined score of 1100 or higher (reading and math); ACT composite score of 23 or higher; two AP exam scores of 3 or greater in English, history, math, or science; or two IB exam scores of 5 or greater in English, history, math, or science.[59] (A combined SAT score of 1100 falls roughly in the 61st percentile, while an ACT composite score of 23 falls in the 75th percentile.)

As with any public policy, there have been several unintended consequences—some good, some bad—of percent plans in university admissions. One positive consequence is that Texas’s top 10% law has made the admissions process for the state’s university system more transparent. Yet a negative consequence of the law is that it has, to some extent, encouraged advantaged students who attend high-performing high schools to transfer to low-performing schools, where competition to rank in the top decile is less fierce.[60] This, in turn, has made it more difficult for disadvantaged students at these schools to win a seat at the state’s public flagship.

With college and university admissions in disarray since SFFA, more states are bound to join Texas, California, Florida, and New York in their use of percent plans for their state university systems. In doing so, both Democrats and Republicans should be cautious that these policies do not simply devolve into affirmative action and are geared, above all else, toward furthering equal opportunity and student success.

Endnotes

Photo: kali9 / E+ via Getty Images

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).