Trimming New York's Budget Bloat: Making City Government Leaner and More Affordable

New York City faces both short- and long-term fiscal concerns as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic. The shortterm issue—keeping the city’s budget in balance despite plummeting employment and the crippling of major industries such as tourism and the performing arts—has proven manageable in the current fiscal year, through the measures the city typically takes in recessions. These include a hiring freeze, deferring expenses to future years, and refinancing debt. A projected deficit remains in the upcoming fiscal year, beginning July 1, 2021, but its size is less daunting than originally forecast, and the city has closed comparable deficits in past recessions.

The long-term problem for the city is that continuing expenditures—particularly on pay and benefits for current employees, as well as pensions and other post-employment benefits for retirees—have risen much faster than price inflation or the growth of the underlying economy. As a result, taxes have grown as a share of the personal income of the city’s residents. The city has, thus far, been able to afford these outsized expenditures principally because property tax collections have continually increased, as scarce office space and apartment buildings become more valuable. Because taxes are based on property values, which in turn are based on achievable rents and sales prices, property taxes can rise rapidly even while tax rates are unchanged. The city has evolved a high-productivity economy whose businesses and workers are able to afford the high real estate costs induced by restrictive land use controls.

These economic arrangements are threatened by the consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic. The city’s key office-based industries have adapted to work at home, and businesses may cut back on office space, forcing landlords to cut rents to fill vacant space. Well-paid workers may find they can live just as easily outside the city if they are no longer going to the office every day. If real estate tax revenue no longer grows well above the rate of inflation, the city’s expenditure patterns will not be sustainable. Furthermore, public officials should be cautious about potential savings from reforming the operations of the Police Department and closing jails, which some have suggested as a means of balancing the budget.

This report suggests that the city plan now for a future in which it has fewer employees, fewer retirees, and lower costs, compared to the levels suggested by current trends. Some of the report’s recommendations include: taking advantage of new technology and international best practices to provide quality services with reduced staff; increasing the use of private contractors for services that are commonly provided in the private sector and in which the city has no special concerns or expertise; reconsidering the level of benefits provided to retirees; and eliminating elected officials, and their staffs, who have few responsibilities and no counterparts in other cities. By beginning now to work down staffing levels and personnel costs to sustainable levels, the city can avoid largescale layoffs and dramatic disruptions in services in the long term.

Introduction

As New York City endures the third quarter of plummeting revenues due to the Covid-19 pandemic, few solutions have emerged to what is likely to be both a short- and long-term fiscal problem. The short-term problem is clear. New York City’s employment and business activity have been severely affected by the pandemic. As of October 2020, the city had lost about 554,000 private jobs, a 13.5% reduction from October 2019, according to the New York State Department of Labor.[1] The city drew heavily on reserves to balance the budgets for both City Fiscal Year (FY) 2020 and FY 2021.[2] Tax revenues in City Fiscal Year FY 2021, which began on July 1, 2020, are expected to be $59.4 billion, down from $61.5 billion in FY 2019, the last economically strong fiscal year.[3] While the city’s FY 2021 budget was considered balanced upon enactment by fiscal oversight entities,[4] considerable risks remained, according to an analysis by the Citizens Budget Commission. On the revenue side, the risks included “possible State cuts to local assistance and tax revenue collections that depend on a recovery starting in calendar year 2021, which recent economic data and the evolving path to controlling the pandemic call into question.” On the spending side, the budget included $1 billion in labor cost savings that had yet to be identified, and perhaps unrealistic assumptions about overtime savings.[5]

The longer-term problem did not begin with the pandemic. Under normal economic conditions, New York City’s economy and diversified tax base produce bountiful tax revenues, and the city spends what it takes in. The largest share of the budget is for personal services, including salaries and fringe benefits. Personal services spending has risen sharply, due to increased payrolls, higher pay, and more costly fringe benefits. In recent years, the city has too often addressed new problems with more city employees, without looking for opportunities to achieve reductions in head count elsewhere. Moreover, the city’s budgeting controls focus on short-term balance and fail to focus on escalating long-term liabilities for pensions and other post-employment benefits (OPEB), mainly retirees’ health insurance. Because city employees are represented by politically powerful labor unions, the city finds it difficult to take benefits away from existing employees. By controlling its head count, pay, and benefits more effectively, the city could not only ameliorate its short-term problems but could establish a sounder fiscal footing for the long term.

Background: How New York City Got to This Point

New York City’s Cash-Generating Machine

Government is expensive in New York. When we want to compare tax burdens across U.S. states, which vary substantially in terms of average wage and salary levels, we look at taxes as a percentage of personal income. In 2017, the latest year for which data are available, state and local tax revenues as a percentage of personal income in New York State were 13.88%, the highest of the 50 states and the District of Columbia.[6]

New York City’s fiscal year runs from July 1 to June 30, and personal income is reported on a calendar-year basis. The average total personal income in the city for calendar years 2016 and 2017 was about $591.115 billion.[7] Total city taxes in FY 2017 were $54.662 billion,[8] or about 9.2% of personal income.

What do New Yorkers get for these taxes? A uniquely high-quality package of public services? An unusually compassionate welfare state? Residents certainly don’t think so. A recent Manhattan Institute survey found that respondents were generally more likely to rate the responsiveness of city government, overall quality of life, public safety, quality of public schools, and cleanliness as average or poor, rather than good or very good.[9] New York City may still be an attractive place for many, given its diverse labor market and cultural amenities, but high taxes, middling services, and expensive housing threaten its competitiveness going forward.

Unlike most American cities, New York City has historically relied on multiple sources of revenue—a tax structure that has effectively extracted revenue from the city’s increasingly diversified and, under normal conditions, prosperous economy. The property tax, usually the dominant source of revenue for local governments, accounted for only $27.9 billion of the city’s $61.5 billion in tax revenue in FY 2019,[10] the last year before the recession induced by the Covid-19 pandemic. Other important tax sources include the personal income, general sales, general corporation, unincorporated business income, mortgage recording, commercial rent, and conveyance of real property taxes.[11]

In addition to being diversified, New York City’s tax sources are bountiful. In FY 2008, the peak of the previous economic cycle, city tax revenues were $38.6 billion; in FY 2001, the previous cyclical peak, tax revenues were $23.2 billion. Thus, over 18 years and two business cycles, city tax revenues rose by 165%, compared with consumer prices, which rose by about 44%.[12]

The rise in tax revenues reflects the high productivity of New York City’s economy.[13] Average private wage and salary employment in the city in 2000 was 3.163 million; by 2019, it was 4.063 million, a 28% increase.[14] Despite this growth, the city’s tax take has risen as a percentage of personal income. In FY 2001, city tax receipts amounted to about 7.8% of personal income, compared with 9.2% in FY 2017, as noted above.[15]

The biggest reason for this change was the property tax, for which collections increased by 238%, from $8.2 billion in FY 2001 to $27.9 billion in FY 2019. Other tax sources nonetheless increased by 125% over the same period, from $14.9 to $33.6 billion, far above inflation.

The property tax is the only New York City tax source for which rates can be raised by the city council without state legislation. However, the rapid growth in property tax revenues is largely due to growth in property values, rather than growth in rates. Although property tax rates were raised in 2003, following the post-9/11 downturn, the rate change accounted for only about a quarter of the revenue growth between FYs 2000 and 2017.[16]

The growth in property values, in turn, reflects both the city’s underlying economic strengths and the scarcity of real estate. New York City notoriously taxes small homes (Class 1 property) at a small fraction of market value while relying mainly on Class 2 property (apartment buildings) and Class 4 (commercial and industrial property, particularly Manhattan office space) for the bulk of its revenues.[17] Because of restrictive zoning, the stock of both residential and office space has been unable to expand to keep pace with the demand generated by the city’s growing economy. Thus, a large scarcity premium has been built in to market rents and sale prices in the city’s highest-demand areas. Through reassessments, the city is able to tax that premium and capture more in taxes, independent of any increases in personal income. This has the effect of forcing up the ratio of tax collections to personal income over time. That, in turn, makes the city less competitive economically but permits large spending increases in good times.

Implications of the Cash-Generating Machine for Policy and Politics

New York City’s cash-generating machine is self-executing, designed decades ago by people who likely didn’t fully understand how the pieces fit together. It is fueled by a growing economy—a condition that has existed most of the time since the city emerged in the early 1980s from the 1975 fiscal crisis.

This state of affairs has three important consequences. First, the budget decisions faced by the mayor and city council are more frequently about spending a surplus, rather than closing a deficit. Second, when the pie is growing, successful interest groups can and do secure increased resources for themselves without necessarily precluding other interest groups from doing the same.

A third consequence is that the pressure for improving productivity—producing the same or greater service outputs with diminished inputs, particularly labor—is, under normal circumstances, very low. New York City can afford to be inefficient.

When agencies feel that they are understaffed or overburdened with responsibilities, the preferred remedy is to add staff, not reduce responsibilities or redesign processes to be less labor-intensive.

City Employment

How this plays out in budget reality is illustrated by Figure 1, which shows full-time staffing levels for the New York City government on June 30 of 2001, 2008, and 2019. Each date represents a high point of spending preceding one of the last three national recessions. The staffing levels therefore can be viewed as a relatively unconstrained view of the city’s needs at a time of peak economic conditions. (For a complete breakdown of city employment growth by agency, see Appendix.)

The city’s full-time staffing rose from 249,824 in 2001 to 280,649 in 2008 and 300,442 in 2019, an increase of 20% over 18 years in which the city’s population grew slowly[18] and information technology, along with the concomitant potential for labor-saving process improvements, advanced rapidly.

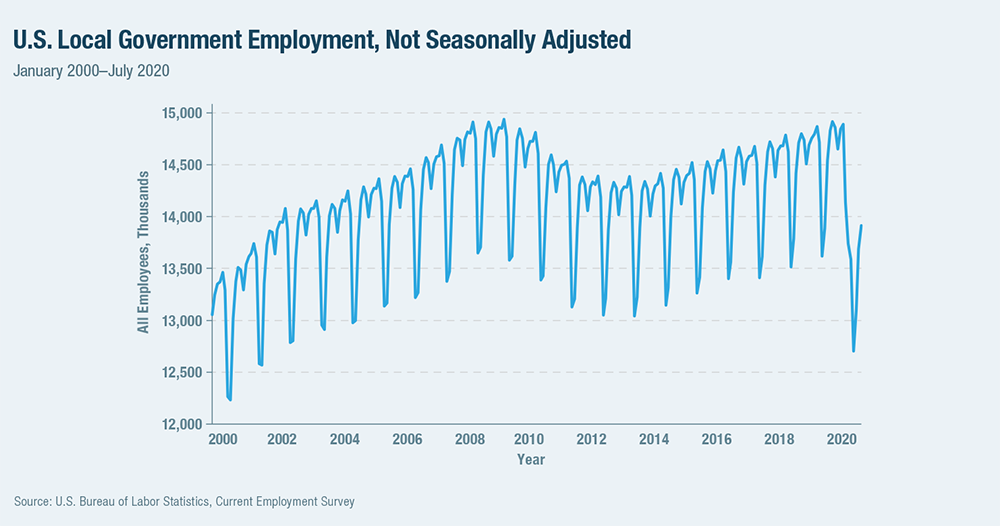

At the national level, local government employment rose from 13.6 million in June 2001 to 14.7 million in June 2019,[19] an increase of just 8%. In contrast, from 2000 to 2018, the U.S. population grew by 16.6%.[20] Thus, relative to population, New York City government employment increased significantly while, throughout the rest of the country, local government employment fell. Notably, local government employment nationally was flat from 2008 to 2019, after growing steeply from 2000 to 2008 (Figure 2). Even with recovery from the Great Recession, local governments did not resume the pre-2008 employment growth path.

The New York City staffing increases were in civilian, not uniformed, personnel. The city’s uniformed services— police, fire, corrections, and sanitation—all saw small reductions in personnel. (However, the police and fire departments added civilian employees.) In contrast, many civilian agencies, with office-based employees using information technology, grew between FYs 2001 and 2019: the mayoralty, for example, by 36%, the Law Department by 38%, and the Department of City Planning by 27%.

Some of the growth in civilian agencies came in areas where the relationship between staffing and improved services may be more direct. The Department of Education added 26,000 pedagogical employees, an increase of 28%. This increase included staffing for the universal pre-K program. CUNY community colleges more than doubled pedagogical staff in a period in which full- and part-time enrollment increased from 63,497 in fall 2001 to 91,715 in fall 2019.[21] The Department of Health and Mental Hygiene increased staffing by 92%, and the Department of Parks and Recreation by 107%.

What is notable about the city’s staffing patterns is not that some agencies got more staff and likely improved services but that there were few offsetting reductions. The largest staffing reduction was achieved by the elimination of the Department of Juvenile Justice, which employed 800 in 2001. The agency was merged into the Administration for Children’s Services under Mayor Michael Bloomberg,[22] but the latter agency’s staffing has remained constant.

Personnel Costs

New York City characterizes direct expenditures on wages, salaries, and fringe benefits as “personal services.” Between FY 2001 and FY 2019, citywide personal services expenditures increased by 131%, from $21.3 to $49.3 billion.[23] Per full-time employee, personal services costs increased by 92%, compared with 44% inflation in the same period, as noted above. Personal services expenditures rose steadily between 2001 and 2019, but the rate of increase accelerated in the later years of economic expansions (2004–07 and after 2015) and slowed down in recessions (Figure 3).

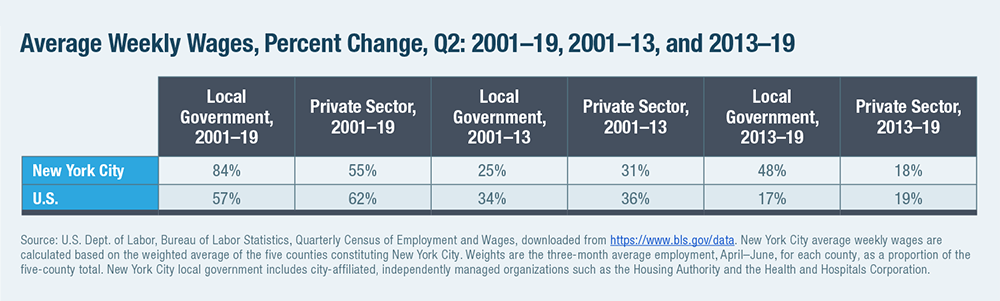

To put New York City employees’ compensation in context, we can compare it with private-sector employees’ wages in the same period. Public employees’ compensation should be pegged to private-sector employment in order to retain a qualified workforce. Figure 4 shows the increase in average weekly wages for government and private-sector employees across the same period—second-quarter 2001 to second-quarter 2019, corresponding to the end of the fiscal year. Comparable national figures are also provided.

The data indicate that during 2001–19, average weekly wages in New York City local government rose much faster than in local government nationally, or in the private sector, locally or nationally. New York City’s increase of 84% in local government wages[24] is well ahead of the 55% increase in local private-sector wages, the 57% increase in local government wages nationally, or the 62% increase in private-sector wages nationally. This outsize growth in local government wages, however, has not been steady throughout the whole period; in 2001–13, New York local government wage growth was only 25%, outpaced by local private sector (31%), national local government (34%), and national private sector (36%). From 2013 to 2019, however, New York City local government average weekly wages increased by 48%, while the other measures increased by 17%–19%, in a period of low inflation. Some of the excess margin for New York City local government wages was catch-up growth; but by the end of the period, the city’s local government workers were well ahead of the private sector locally or nationally, as well as local government peers across the country.

Figure 5 shows New York City local government wages lagging, and then spiking in the past few years, coinciding with the mayoralty of Bill de Blasio. The rise in wages is a boon to city employees but a burden for city taxpayers, especially as a recession struck in 2020 and now that the city is looking at several years of constrained finances.

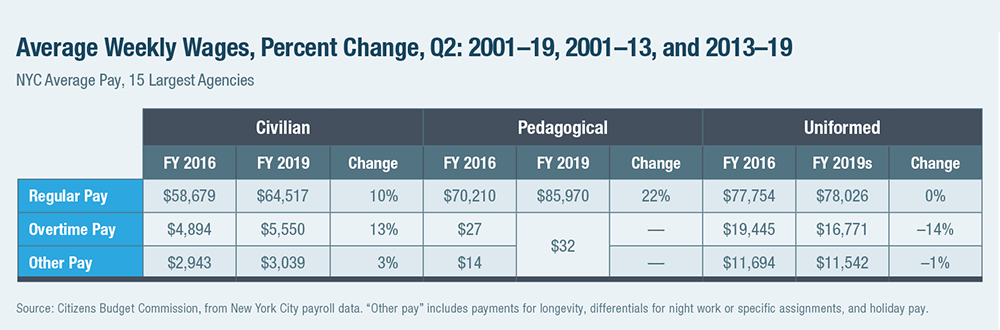

Data compiled by the Citizens Budget Commission (CBC)[25] provide insight into how this spike in pay has been distributed to city employees. CBC compared average annual total pay in the 15 largest city agencies for civilian, pedagogical, and uniformed employees (Figure 6). For civilian employees, from FY 2016 to FY 2019, average annual regular pay rose by 10% and overtime pay by 13%. For pedagogical employees, regular pay rose by 22%. For uniformed employees, the rise in average regular pay was negligible, and average overtime pay fell. Inflation was about 6.2% in this period.

Teachers are thus the largest beneficiaries of the spike in average local government pay. Teachers’ average annual regular pay increased from $78,556 in FY 2016 to $97,093 in FY 2019, or 24%, according to CBC. In 2014, Mayor de Blasio agreed with the United Federation of Teachers on pay increases of 18% over nine years.

New York City’s Fiscal Dilemma

Wage growth for city employees is not the whole story. As CBC points out, the current costs for every city employee include not only a wage or salary (including overtime and other special allowances) but also health insurance and other welfare-fund contributions, such as dental and vision benefits. In FY 2018, CBC found that health-insurance costs amounted to $15,153 per employee.[26]

Much of the cost of a growing government workforce is long-term. In addition to a defined-benefit pension plan, the city provides retiree health insurance and welfare-fund contributions for retirees, known as other post-employment benefits (OPEB). While pensions are pre-funded on an actuarial basis, OPEB are funded out of current spending. However, the city’s annual pension contributions have become very large in dollar terms. Pension costs were $9.9 billion in FY 2019 and are expected to be $9.8 billion in FY 2021, staying at or above that level for the next several fiscal years. The city faces the possibility of having to make additional contributions, on the order of hundreds of millions of dollars, because the pension funds may be unable to earn the target 7% return on investments in the current environment of very low-interest rates.[27]

CBC found in 2018 that annualized pension and OPEB costs per full-time employee were much higher for uniformed workers than for pedagogical or civilian workers. For each uniformed worker, annualized pension costs were $13,242 and OPEB expenses were $19,273; for pedagogical, $5,561 and $11,277; and for civilians, $4,620 and $10,908.[28]

A second CBC study from 2017[29] provides insight into why OPEB costs are higher for the uniformed services. Of $95.1 billion in Actuarial Accrued Liability (AAL)[30] in FY 2017, $32.2 billion comes from pre-Medicare health-insurance costs; the city pays the full costs of the basic health plans used by most retirees. Because uniformed personnel can retire at a younger age and thus spend more time in retirement before qualifying for Medicare at age 65, $15.6 billion of the pre-Medicare liability comes from police and fire department retirees. In contrast, retired police and fire personnel account for a much smaller share of Medicare premiums, which, in turn, account for much of the remaining liability, along with welfare-fund benefits (dental and vision).

CBC found that New York City’s OPEB liabilities, when standardized for the number of participants, were much higher in 2016 than for most comparable U.S. cities. “The dominant reason for lower liabilities in other cities,” according to the report, “is that their promised benefits are less costly.” Jurisdictions with lower liabilities do not cover the full cost of health-care premiums for retirees or fully reimburse Medicare Part B premiums.[31]

The upshot of New York City’s high and rising employee costs is that New York City’s fiscal stability is continually threatened by the high costs of its government. As noted above, New York City has evolved a strategy of taking advantage of ever-higher property values resulting from scarcity induced by restrictive zoning. It captures a portion of these increases in value through the property tax. That, in turn, is the primary means by which spending can rise faster than inflation in good times.

This property scarcity has pushed the city’s economy in the direction of high-productivity industries that can afford not only the high commercial rents for itself but also to pay employees well enough for them to afford the expensive housing market. The framework is highly vulnerable to recessions in general but particularly to the current one. It is at least plausible that high-productivity firms will downsize their office space, as employees work from home at least part of the time, thus forcing commercial landlords to drop asking rents to fill the newly vacant space. Managerial and professional workers, less tied to the office, may move their primary residences outside the city and stop paying city income taxes. Others may downsize or give up their pieds-à-terre. These actions would reduce demand for high-end residences.

The effect of these trends would be to slow the growth rate of property tax collections, even as the city’s economy recovers. Since the city has depended on outsize property tax growth to balance its budgets despite rising personal services costs, moves toward greater workforce productivity and efficiency today would help sustain the city’s ability in the future to provide services at the level that the public has come to expect.

Rationalizing New York City’s Public Workforce

For New York City to continue to prosper, it may need to adjust to a new tax environment, markedly different from that of the past 40 years. To make this adjustment, the city should rationalize the size and cost of its workforce so that it is compatible with at least several years of a contracted economy and a weaker tax base.

A workforce rationalization plan goes beyond the very important task of eking out savings from year to year to keep the current year’s budget in balance. It considers how the city can employ technology and best practices from around the world to provide services at lower cost at the same quality, or perhaps even better quality. Improved productivity can provide a fiscal cushion, which can be used to fill larger-than-anticipated budget gaps in the coming years or, in the best-case scenario, to cut taxes or improve services.

New York City’s November 2020 Financial Plan Update reflects a somewhat improved picture, compared with the June plan. The FY 2021 budget remains balanced, while the city’s improved revenue outlook and control of spending allow for the prepayment of $632 million in expenses for FY 2022. The projected gap between revenues and expenditures in FY 2022 is down to $3.75 billion, from an anticipated $4.2 billion in June.[32] Mayor de Blasio had proposed earlier in the year to address budget shortfalls by borrowing $5 billion to support the city’s continued high spending. But this requires state legislation, which has not been forthcoming.[33] Even if the state did allow it, this borrowing would simply push the city’s problems off to the future while increasing the city’s cumulative liabilities—not only debt service but also pensions and OPEB, as employees accrue more years of service. Reducing the size of the workforce, as well as other measures that permanently reduce the city’s personnel costs, are greatly preferable.

Reducing the Cost of the City’s Workforce

There are many ways to achieve reductions in head count of city employees. De Blasio had threatened to lay off 22,000 workers to save $1 billion if he could not obtain either debt-authorizing legislation from the state, other cost-saving concessions from unions, or additional federal aid. However, he repeatedly postponed the layoff deadline, and then dropped the threat in return for short-term union concessions. On October 9, an arbitrator delayed half a promised $900 million bonus payment for teachers until July 2021. This helps the city balance its FY 2021 budget while increasing the projected deficit for the following year. However, the arbitrator also took teacher layoffs off the table at least until FY 2022.[34] Then, later in October, the city’s largest union, District Council 37, agreed to defer $164 million in welfare-fund contributions to FY 2022. Again, the mayor took layoffs off the table, until the end of the current fiscal year.[35] Additional union deals took the total amount of one-year deferrals to $722 million.[36] In early November, de Blasio announced support for an early retirement bill in the state legislature, which ostensibly could save the city $900 million over four years, including $250 million in the first year.[37] The labor concessions thus far do not achieve the projected $1 billion in savings but are enough to keep the FY 2021 budget balanced. De Blasio is, in effect, counting on postelection federal aid to get the city through FY 2022. However, as of December 2020, the political outlook for such aid remained uncertain.

Layoffs may still happen, given that alternatives were not pursued earlier in the 2020 calendar year as the city’s deteriorating financial situation became clear. However, layoffs are an undesirable means to cut staff. The least experienced employees are laid off first, even though those employees may be better trained for current needs than older employees with longer tenure. There are better alternatives that could help close the gap in FY 2022 and beyond. In a September 2020 report,[38] CBC proposed several productivity measures that could potentially reduce the size of the city’s workforce:

Job assignment flexibility: Job titles are redefined to create flexibility and allow more workers to perform necessary tasks.

Lengthening the workweek: Workweek is defined as 40 hours for all workers.

Eliminating the “absent teacher reserve,” a category of teachers who are paid full-time salaries but do not have teaching assignments. CBC notes that recent efforts have already achieved large savings in this category.

Consistent staffing of fire companies: Currently, most fire companies have four firefighters and one officer, but up to 20 companies may have five firefighters and one officer under current labor agreements.

Other measures proposed by CBC would not necessarily reduce the number of city employees but would reduce personnel costs in the short term and, in some cases, the long term. These include a wage freeze, shifting health-insurance costs to employees and retirees, reductions in other fringe benefits, a cap on overtime for certain categories of employees who are now exempt, ambulance staffing flexibility, and reform of pay differentials provided under some union contracts.

Most of CBC’s budget cuts would need to be negotiated with city unions, which historically have been unwilling to give up benefits previously achieved through collective bargaining. However, during the Bloomberg administration, the city was able—through state legislation— to achieve a new, less generous, pension plan for new employees, which reduces future costs.[39] Similarly, the city may be more likely to achieve health-insurance cost-sharing for retirees through state legislation. A 2013 CBC study found that New York State retirees are required to share in health-insurance costs both prior to qualifying for Medicare and afterward.[40] A successful negotiation with city unions, or legislation setting the same standards for the New York City government, would help stabilize the city’s long-term finances. A recent report from John Hunt suggested restructuring OPEB benefits as a Retiree Medical Trust (RMT), as is the practice in other states. The advantage of an RMT is that the government’s contribution is fixed, rather than open-ended, as at present.[41]

Similarly, Hunt recommends that the city moves toward a defined-contribution pension plan, in which the city would not be required to make additional contributions in the event of inadequate investment returns, so that retirees receive guaranteed benefits. Rather, in a defined-contribution plan, the city’s contribution would be capped, and retirees would bear the risk of low returns. In 2012, former mayor Michael Bloomberg proposed an elective defined-benefit pension plan for new employees that would vest after one year and be “portable” if the employee left city service.[42] A voluntary defined-contribution pension plan along these lines would be attractive to some new employees, who do not intend to make a career in city government, while saving the city money.

The city should explore other voluntary alternatives— which may be more achievable—such as buyouts. Another possibility with long-term savings potential, which de Blasio has now endorsed, is an early retirement incentive.[43] Provided that the incentives are carefully targeted to job titles where staff provide nonessential services, and retirees’ jobs are eliminated rather than refilled, borrowing to fund the incentive can be repaid with part of the savings.

As shown in Figure 7, there are several city civil service titles for which, as of FY 2018 (the last year for which data are available), there were more than a thousand employees; the number of employees fell between FY 2015 and FY 2018 (despite the general rising trend in city employment); the median age is 50 or older; and the number of separations in FY 2018 exceeded new hires, implying less than a one-for-one replacement. These titles have many employees at or close to retirement age and represent obvious targets for an early retirement program.[44] For example, the number of clerical associates declined by 15% in just three years. It is likely that because of evolving technology, the city needs far fewer employees in this title than it once did. Looking for ways to encourage the aging cadre of remaining employees in this title to retire or train for new positions could result in considerable savings.

Incentives to leave city service do not need to be targeted to workers who are at or close to retirement eligibility; in FYs 1994 and 1995, the city offered a severance incentive to employees independent of retirement eligibility.[45] The city could also offer incentives for retraining or reassignment to other titles for which new hires would otherwise be necessary. However, employees with the greatest longevity are also the highest-paid, making retirement incentives fiscally efficient. The next section of this report examines how productivity improvements combined with staff attrition, or employee buyouts funded by a portion of the savings achieved, can help the city move toward long-term fiscal sustainability.

Finding Productivity Savings

Uniformed Services | Police

As noted above, uniformed services (police, fire, corrections, and sanitation) are the best-paid, on average, of all city employees. The data in Appendix Table 1 on the number of city employees by agency and uniformed/ civilian status at different points in time indicate that, aware of pay differentials, the past two mayors have sought to reduce, or at least keep constant, uniformed head counts. The huge increases in city employment since FY 2001 have been driven by civilians, not uniformed personnel.

The number of uniformed police, for example, fell by about 3,000 from FY 2001 to FY 2008, and then rose again by about 1,000 by FY 2019, to 36,461. Mayors have long used police attrition as a budget balancer, and the city’s FY 2021 adopted budget does that again, canceling the July 2020 police academy class, among other actions, for a total reduction of 1,171 uniformed personnel.[46]

Reductions in uniformed police personnel are always politically fraught, with the fear that the police may be understaffed and unable to control rising crime. Rising crime in the city has certainly brought such concerns to the fore.[47] What makes the current political environment unusual is the existence of an organized nationwide movement to “defund the police,” which, in practical terms, means to fund the police less. At the same time that New York was adopting its latest budget, the Los Angeles City Council voted to cut its proposed $1.86 billion police budget by $150 million.[48] The vote came after the council voted to replace police officers with unarmed crisis response teams for calls related to mental health issues, neighbor disputes, substance abuse, and other situations where armed law-enforcement personnel may not be the best people to handle the problem.[49]

In August 2020, the Austin, Texas, city council voted to cut its police budget by $150 million, about one-third. The Austin changes included a freeze on hiring and a $50 million allocation to a “Reimagine Safety Fund” for “alternative forms of public safety and community support.”[50] In July 2020, a report by the New York State attorney general’s office recommended the formation of a study commission that, over 12 months, would prepare a “road map” to “transition” away from police officer involvement in mental-health crisis intervention, school safety, traffic enforcement, and homeless outreach.[51]

These proposals have come in response to claims of excessive police violence, but any change in the way in which public safety is managed has fiscal implications. While these proposals might seem to offer savings, experts are skeptical that a successful civilian-based alternative model of community order and peacekeeping can emerge from these urban experiments.[52] While using civilian responders may be a good idea in some situations, they may need to be accompanied or backed up by police in case a situation becomes violent. In that case, civilianization, even if better, would be more, not less, costly than current policing. New York City should be skeptical that these proposals’ promised savings would actually materialize.

Uniformed Services | Fire

Fire Department uniformed staffing has changed little since FY 2001. However, perhaps it should have changed: in a 2015 report, CBC found that fire responses had declined sharply since the merger of FDNY and the city’s ambulance services in 1996. At the same time, the number of medical incidents to which FDNY responded had increased by a third. “The number of medical incidents to which the FDNY responds is about 15 times that of fire-related incidents and more than 30 times that of structural fires.” Nonetheless, “the merger was not accompanied by a fundamental transformation of the organization and staffing of the FDNY. As a result, the FDNY does not efficiently address its most common job: responding to medical emergencies.”[53]

A follow-up report in 2018 explained the problem in more depth.[54] The specific problem is that fire engine companies are frequently sent to respond to medical emergencies in addition to, rather than in lieu of, an ambulance: “The use of fire engines in addition to ambulances as a response to medical incidents is wasteful; the heavily staffed fire engines are far more expensive than ambulances as a response, and in many of the incidents to which they respond, fire engine personnel are not able to deal effectively with the medical condition.”

The report notes that “despite their high cost and limited effectiveness, the use of engine companies as responders to medical incidents has been continued by FDNY as a pretext for sustaining the staffing of otherwise unnecessary fire engine companies. In 2010, the Bloomberg administration unsuccessfully proposed closing 15 fire engine companies primarily due to the declining workload related to fires and other emergencies.” At the time, the average salary for a firefighter was $73,913, considerably more than that of a paramedic or an emergency medical technician. Because of this higher pay and because fire engines are more heavily staffed, the estimated average cost of a fire engine response to a medical emergency was $1,970, while the average cost of an ambulance after reimbursements was $335. The report concludes that “reduced reliance on fire engine response to medical incidents can yield savings by reducing the number of fire engines to reflect their reduced workload; staffing each fire engine costs about $7.2 million annually, and these resources could be reallocated to higher priority services.”

Few budget-cutting actions are more politically difficult than closing firehouses or even reducing the number of fire companies. Voters fear the loss of fire protection even if the data clearly suggest otherwise. Other financially strapped cities have been forced to consider such cutbacks. In Baltimore, the budget adopted in June 2020 by the city council for FY 2021 includes disbanding two fire companies; savings are projected at $3 million, out of a total budget of about $300 million.[55] New York City needs to match such measures at its much larger scale.

Uniformed Services | Correction

Department of Correction uniformed employment was also stable in recent decades, with 10,189 correction officers in FY 2019, just a few hundred fewer than in FY 2001. However, unusually for the de Blasio administration, the mayor’s executive budget already included significant staff reductions in FY 2021 in connection with the closing of facilities on Rikers Island, as inmate counts go down with bail reform and Covid-19 safety measures. The projected reduction amounts to 2,570 uniformed corrections personnel.[56] As of August 2020, New York City’s average daily jail population had fallen by 43% since August 2019, to 3,972.[57] In November, however, the average daily jail population had risen to 4,612.[58] City officials attributed a 16% increase in the pretrial detainee population to a partial rollback of earlier bail reform legislation—which made bail an option again for some crimes for which it had been prohibited by the original law—as well as an increase in violent felony arrests, particularly for gun crimes, throughout the violent crime spike of the past few months. Whether forecasted reductions in the jail population will be sustained is uncertain, given recent crime trends. NYPD leaders and some elected officials, as well as commentators, believe that there might still be too few accused criminals detained.[59] If the jail population reductions are sustained, that would enable significant reductions in the number of uniformed correctional staff, regardless of the ultimate progress of the plan to close Rikers Island entirely and replace its jails with four new facilities in the Bronx, Brooklyn, Manhattan, and Queens. The 2026 deadline to close Rikers Island has been endangered by budget cuts[60] and a recent adverse court decision in state supreme court in Manhattan.[61] In October 2020, the city extended the deadline to 2027.[62]

Other cities are also finding budgetary savings from declining jail populations as a result of bail reforms. In St. Louis, the Board of Aldermen voted in July 2020 to close one of the city’s two jails, known as the Workhouse, which had cost $16 million a year to operate.[63] Philadelphia has announced the closing of its oldest jail, the House of Correction.[64]

Uniformed Services | Sanitation

The Department of Sanitation had 7,893 uniformed personnel in FY 2019, a similar number as in FY 2001. The FY 2021 Executive Budget included a reduction of 383 uniformed positions as a result of ending or suspending various service initiatives.[65]

The department has been unable to implement the widespread use of on-street garbage bins and trucks with mechanical lifts, despite these being common in many other cities around the world. These mechanisms minimize direct employee contact with trash and reduce injuries. The use of sealed containers, meanwhile, helps keep streets and sidewalks clean and prevents rodent infestation. Most important, fully automated collection trucks allow for one-person truck operation. A 2014 CBC study found: “Even with the higher upfront and ongoing maintenance costs for automated trucks, DSNY’s labor costs are high enough that each fully-automated, one-worker truck could save more than $100,000 annually.”[66] At current salary and fringe benefit levels, the savings per added one-person truck would be much higher.

An obstacle to the increased use of bins and automated trucks is the city’s design; New York does not have rear alleys to facilitate trash pickup. However, one way to overcome this problem on typical residential blocks is to assign several parking spaces for the storage of trash bins.[67] While eliminating parking spaces may be controversial in some neighborhoods, the city’s successful experience with on-street dining areas during the Covid-19 pandemic may open up other possibilities for the innovative use of street space.

A trash-bin system also makes possible volume-based solid waste fees, based on the size and weight of the bins used by each customer. By imposing higher fees on nonrecyclable waste, such a system could facilitate compliance with the city’s residential waste stream diversion goals. This has been the experience in large, dense cities—San Francisco, San Jose, and Seattle—with the nation’s highest residential diversion rates.[68] The city should begin implementing innovative practices that have become routine in other large cities.

Civilian Employees

Privatization The increases in city civilian staff from 2001 to 2019 took place across a wide range of agencies. It’s likely that the city genuinely needed these new hires to address service needs. However, the city should have considered whether private contractors could have provided these services—and, at the same time, whether there are opportunities to replace other staff with private contractors. To avoid not only the current burden of salaries but ever-increasing long-term liabilities for pension costs and OPEB, the city should explore whether new and existing services can be provided privately rather than by city employees.

Many city services are not suitable for privatization. Those that require special skills or training, or sensitivity to the nuances of New York City’s diverse population, are not easily procured in the private sector and are best assured by direct control and supervision by public officials.

However, in many of the city’s administrative functions, the services that it provides are similar to those routinely supplied by the private sector. For example, one of the largest percentage increases in staffing recorded over the past two decades is in the Law Department, which increased from 1,151 to 1,714 employees between FY 2001 and FY 2019. About half the employees in the department are lawyers,[69] and it is reasonable to ask why the added workload could not be contracted out to private law firms.

In another example, in 2018 the city employed 2,906 senior school lunch helpers and 4,034 school lunch helpers.[70] While these roles, all part-time jobs, are necessary, the city has no special expertise in serving lunch to schoolchildren, and private cafeteria operation is widespread in New York City and elsewhere in this country and easily procured.

The Fire Department saw a large increase in civilian employment between 2001 and 2019, from 4,306 to 6,093. One major reason is the rise in medical emergencies, both life-threatening and non-life-threatening. From 2000 to 2017, the total number of FDNY medical incidents rose by 39%.[71]

FDNY responds to non-life-threatening incidents with Basic Life Support (BLS) ambulances, which carry two EMTs. As of 2017, city employees staffed about 71% of the average 806 BLS tours per day. Private ambulance companies staffed the rest. From 2014 to 2017, the number of public BLS tours increased while the number of private tours stayed the same.[72]

CBC makes several recommendations to reduce the costs of non-life-threatening responses, focusing on reducing the unnecessary use of medical services.[73] An additional focus should be on reducing the long-term fiscal effects of expanding the city payroll. In Washington, D.C., the local government addressed the rising number of non-life-threatening emergency medical calls by contracting with a private company, American Medical Response. The contract has helped stabilize response times and enabled D.C. employees to address the highest-priority calls. Like New York City, D.C. has a problem of inappropriate use of emergency medical resources and is concurrently undertaking measures to reduce unnecessary calls.[74]

The city does, from time to time, privatize services that it once performed itself. For example, city agencies once bought their own office supplies and maintained supply rooms in their offices. In 1996, the city contracted with Staples Business Advantage to deliver supplies directly to all city agencies.[75] This saved the city storage costs and ensured the lowest bid price for supplies. Similarly, the city once maintained a motor pool for city employees. In 2016, it contracted with Zipcar to provide on-demand transportation for city employees. This has enabled the city to reduce its fleet by 1,000 vehicles.[76]

Privatization is clearly more difficult when labor-intensive activities are involved, since employees usually have union representation that will often fight against it. The city was able to privatize occupied “in-rem” housing in the 1990s.[77] These properties had been taken by the city for nonpayment of real-estate taxes and were costly to manage and maintain. Workers in these buildings, however, had not been represented by any of the city’s municipal unions.

In many cases, privatization can be accomplished without the loss of city workers’ jobs. For example, senior school lunch helpers had a separation rate of 11.7% in FY 2018, and school lunch helpers 9%.[78] The city could initiate a privatization program by contracting out staffing at some school cafeterias rather than replacing all departing employees.

In smaller cities, service privatizations have been accomplished by shifting union employees to the private sector. For example, in Scranton, Pennsylvania, the wastewater system was privatized in 2016, with the new owner offering jobs to the 80 unionized employees. The privatization relieved the municipal sewer authority of debt and responsibility for future upgrades to bring the system into environmental compliance.[79] In Nassau County, New York, privatizations have been more controversial and problematic. While the county legislature approved a private management contract for the county’s sewer system, shifting employees from public to private payrolls has proved difficult.[80]

Redundant Elected Officials

Some of the few city agencies that have had actual significant staff reductions from 2001 to 2019 are the five borough presidents and the public advocate. These six officials’ positions are artifacts of the 1989 amendments to the city charter, which eliminated the Board of Estimate (BOE), a de facto legislative body that was ruled unconstitutional because of its unequal representation. The charter change stripped former BOE members of nearly all their powers while allowing them to keep their jobs, salaries, office space, and staff.

The staff reductions of the past two decades are justified by diminished responsibilities, but the city needs to face another question: Why does New York City need six largely ceremonial elected officials who have no counterparts in other large cities? Essentially, taxpayers provide a platform for an aspiring politician who gets to criticize the decisions of the mayor and city council but ultimately bears no responsibility for the tough choices that they necessarily have to make. Often these vestigial offices are simply springboards to more powerful elective offices: after serving as public advocate, Letitia James went on to become state attorney general and Bill de Blasio to become mayor. Both had previously been members of the city council. It’s hard to argue that they got useful additional experience by occupying the largely powerless office of public advocate.

Abolishing the offices of borough president and public advocate would streamline the structure of city government, creating clear lines of responsibility and saving money. The city’s elected officials would be the mayor, the 51 members of the city council, and the comptroller. The City Planning Commission could be reduced to seven members appointed by the mayor, as was the case prior to 1989. The city’s land-use review process timetable could be reduced by 30 days, as there would no longer be an advisory review by the borough president. The borough perspective in the land-use process would still be represented by the relevant city council members. The comptroller would continue to be the city’s independently elected fiscal watchdog. The city’s savings would be $34.9 million in budget allocations, not including fringe benefits allocated on a citywide basis, and the value of the free office space provided in city buildings. The number of full- and part-time positions that could be eliminated is 345.[]81]

Conclusion

New York City faces an adverse fiscal situation for a recovery period whose duration is difficult to predict, but which could last several years. To address the short-term fiscal problem, layoffs might be unavoidable. The typical practice in city government has been to restore staffing levels as soon as the economy improves, and then add more employees if the economy remains strong. However, New York City’s long-term economic competitiveness and ability to provide a high standard of public services are threatened by a high tax burden and excessive public employment. Sound budgeting practice demands that the city embarks on a long-term plan to control its personal services costs and long-term pension and OPEB liabilities. By taking advantage of technology and best practices from local governments across the nation and the world, and through administrative reforms, the city can achieve efficiencies that enable it to reduce head counts. If these reductions come through normal attrition, buyouts that share the fruits of genuine savings, and transfer of responsibilities typically provided in the private sector to private contractors, the city can preserve service quality and avoid the disruptions that accompany layoffs.

The city knows how to achieve long-term efficiencies. During the early years of the Giuliani administration, the cash-strapped city merged the Transit and Housing Police Departments with NYPD. The city’s Emergency Medical Service was shifted from the Health and Hospitals Corporation to the Fire Department, and the Department of Personnel was merged with the Department of General Services to form the Department of Citywide Administrative Services. The Giuliani administration also merged the capital construction divisions of several city agencies into a new Department of Design and Construction. All these changes have endured and are widely accepted as sensible. The city in the Giuliani years also privatized the city’s remaining occupied in rem housing and instituted a policy of selling tax liens at auction rather than foreclosing on delinquent properties. (This last policy was successful for decades but has become controversial in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, in which many landlords, troubled by rent delinquencies, have fallen behind on property taxes.)[82] Additionally, it sold a city-owned commercial television license and a hotel, and it transferred the city’s public radio station to a nonprofit foundation.

Mayor Bloomberg also consolidated agencies, merging the Department of Juvenile Justice into the Administration for Children’s Services and accomplishing the merger of the Department of Health and the Department of Mental Health, Mental Retardation and Alcoholism Services, first proposed by Giuliani.[83] Bloomberg also successfully secured a pension reform, albeit not as ambitious as his original plan.[84]

The city should apply these lessons about how services can be provided better and at lower cost to its other uniformed services and, indeed, to its civilian agencies as well. Adding public employees when a new service need arises should be a last resort, not a default option. Local government employment nationally stayed level over the last business cycle, even as the U.S. added population. If New York City can do the same, getting city employment down merely to the levels of 2008, it can also reduce its high tax burden and leave more resources in the hands of its residents and businesses.

Appendix and Endnotes

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).