The Radical Movement to Divest from Youth Residential Treatment

Executive Summary

Amid an unprecedented youth mental health crisis, a movement to divest from residential treatment—an essential resource for children with severe emotional and behavioral needs—has gained significant traction. The number of residential treatment programs declined by 61% between 2010 and 2022, not because of reduced demand or lack of efficacy but because of growing policy resistance and ideological opposition.[1]

Fueled by celebrity influence and activist rhetoric, critics have cast residential treatment in a uniformly negative light, equating it with abuse.[2] This narrative has driven legislative efforts to restrict federal funding, impose additional regulations, and discourage its use.[3] If successful, these measures risk further limiting treatment options for families whose children require intensive care, leaving many without the support they urgently need.[4]

Critics rely on five central claims to advocate against residential treatment:

- Abuse in residential treatment is systemic. Evidence suggests that incidents of abuse, while unacceptable, are isolated and not representative of the entire sector.

- Residential treatment is ineffective and harmful. Treatment outcomes vary based on the quality of programs and the extent to which individuals engage in their treatment plans; many studies demonstrate positive results.

- Residential facilities are unregulated. Residential treatment is regulated by state agencies, with many facilities also subject to federal oversight and obtaining independent accreditation to ensure compliance.

- Profit motives override patient needs. For-profit and nonprofit facilities face similar challenges, and profit status alone does not determine quality of care.

- Home- and community-based services (HCBS) are universally better alternatives. HCBS and residential treatment serve distinct but complementary roles; residential care is designated for youth with acute needs, deemed medically necessary for those who cannot safely remain at home.

This report examines the critical role of residential treatment, responds to each of these five claims, and proposes actionable policy recommendations to preserve and improve this vital resource. These recommendations include:

- Revise the Family First Prevention Services Act (FFPSA) to improve funding accessibility for residential treatment facilities.

- Repeal the Medicaid IMD Exclusion to simplify reimbursement processes and incentivize residential care capacity.

- Allocate resources to help families identify and access safe, high-quality residential treatment programs.

- Prioritize reforms that enhance safety and effectiveness without reducing access.

- Incorporate diverse perspectives in policymaking, including the voices of families and individuals who have benefited from residential care.

Introduction

Residential treatment for youth includes a wide range of public and private programs designed to address mental health and behavioral challenges. These programs vary widely, encompassing wilderness “boot camps,” ranch-based operations where youth engage in agricultural work, equine therapy retreats, therapeutic boarding schools, less restrictive group homes, and intensive facilities designed for youth with acute needs, among other programs.

Often collectively referred to as the “troubled teen industry,” this term has been popularized by activists, particularly self-identified “survivors” of outdated programs from the 1970s to the early 2000s. Through media exposés, podcasts, and documentaries, these activists have highlighted emotionally charged anecdotes of alleged past abuses.[5] While these stories have shaped public opinion, they are largely disconnected from the modern treatment landscape, which emphasizes evidence-based practices (EBPs) and improved standards of care.[6]

Residential care differs across key dimensions, including function, target population, length of stay, level of restrictiveness, and treatment approach.[7] Youth access residential care through various child-serving systems, including child welfare, mental health, juvenile justice, education, and private family placements.[8] Some programs specialize in addressing specific challenges such as substance abuse, eating disorders, developmental delays, or behavioral rehabilitation for youth involved in the justice system, including youth sex offenders.[9]

Residential care for youth has seen a sharp decline in availability. Since 2010, the number of residential treatment centers has decreased by 60.9%, and the number of beds has fallen by 66.2%. The decline has accelerated since the passage of the Family First Prevention Services Act (FFPSA) in 2018, which shifted funding toward home- and community-based services (HCBS). The number of children served in residential treatment facilities has dropped even more steeply since 2010, declining by 77.9%.[10]

Accurately estimating the number of youth served annually in residential treatment is challenging. In 2022, three systems reported the following figures: 33,728 youth in child welfare, including group home and institutional settings;[11] 8,544 youth in mental health residential treatment centers;[12] and 27,587 youth in juvenile justice residential facilities.[13] However, these sources, illustrated in Figure 1, are not necessarily mutually exclusive, and overlap between systems is possible.

Psychiatric residential treatment facilities (PRTFs) represent one of the most intensive forms of residential care, serving youth with acute psychiatric needs.[14] Staffed by multidisciplinary teams of licensed nonmedical staff and medical professionals, these facilities provide comprehensive services, including individual and group therapy, psychiatric evaluations, medication management, medical care, and educational programming, alongside 24-hour supervision in a highly structured environment.[15] Patients live together in a group setting, where they develop social skills and practice conflict resolution. In the past few decades, these facilities have increasingly adopted EBPs such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT), and trauma-focused interventions to enhance the quality of care provided.[16]

Youth in PRTFs often face severe emotional and behavioral challenges.[17] Many pose a danger to themselves or others, engage in self-harm, or exhibit psychotic symptoms or aggressive behaviors. Some are at risk of or are already engaging in criminal behavior, making residential treatment a necessary intervention. Admission to these facilities is reserved for individuals deemed medically necessary and is typically considered a last resort when less intensive options, such as outpatient or community-based services, have proved insufficient.[18]

PRTFs have seen a 21% decline in numbers since 2010, with reductions exceeding 30% in 12 states.[19] This shortage has made it difficult for families to access the care that their children need.[20]

Narrative 1: Abuse in Residential Treatment Is Systemic

Opponents of residential care often allege that it is abusive. High-profile incidents of abuse at certain facilities have garnered significant media attention, amplified by reports from advocacy organizations and government investigations, which have raised concerns about the safety of all residential treatment centers.[21]

A prominent example is the 2024 Senate Committee on Finance (SCF) report, produced after a two-year investigation, titled “Warehouses of Neglect: How Taxpayers Are Funding Systemic Abuse in Youth Residential Treatment Facilities.”[22] The SCF report alleges that abuse in youth residential treatment facilities (YRTFs) is “routine” and “systemic” and that mistreatment is “endemic” to the treatment model itself, condemning residential treatment in the strongest terms. However, several issues with the report’s methodology and scope cast doubt on the validity of these sweeping claims.

The investigation was initially intended to examine four major residential treatment providers over a five-year period (2017–22). These providers fully cooperated, submitting thousands of pages of requested documentation. Despite this, the report draws on incidents dating back nearly 30 years, significantly broadening the scope beyond its stated focus.

Additionally, the report relies on unsubstantiated accounts from unidentified facilities.[23] It also includes findings from visits to facilities unrelated to the four providers under investigation, despite committee staff being invited to visit the facilities actually under review.[24] These speculative observations detract from the report’s reliability and dilute its focus on the four major providers.

The investigative findings section[25] combines news stories with internal documents provided by the companies, many of which recount incidents already detailed in public reporting. This repetition could create the misleading impression of more instances of abuse than were actually identified.

Furthermore, the report relies heavily on a narrative approach, cataloging specific abuse and substandard-care instances without offering statistical analysis to contextualize these findings. While a report of this nature could be useful for identifying discrete problems within certain facilities, it undermines its credibility by generalizing these findings to all facilities.

For instance, the SCF report cites[26] numerous calls to police regarding abuse but omits that most of these allegations were not substantiated.[27] Of the confirmed claims, SCF reported approximately 50 incidents each of physical and sexual abuse by staff. The majority of sexual abuse incidents were identified through a 2020 Philadelphia Inquirer investigation, which found 40 cases over 25 years at Devereux, a nonprofit facility provider.[28] Additionally, public reporting found 25 physical abuse incidents at Devereux facilities. According to the Inquirer, Devereux facilities house approximately 5,000 children annually across nine states. Given the vast number of youth served in these settings, the incidence of abuse reported by SCF is relatively low.

A detailed rebuttal by Universal Health Services (UHS), one of the four providers investigated by SCF, further challenges its claims.[29] UHS provided context showing that abuse is extremely rare in its facilities. SCF cited five incidents of inappropriate sexual contact at three UHS facilities over six years (2017–22), during which UHS treated about 19,000 patients across 59 facilities. Internal data for the past four years show a patient risk rate for such incidents at 0.003%. For physical harm from staff over the past three years, the risk rate was 0.015%. UHS argues that these rates do not support the narrative of pervasive problems or unsafe environments, as 99.985% of residents did not encounter such situations.

When serious incidents occur, facilities are required to report them to oversight agencies, such as the state Child Protective Services (CPS). The committee’s review acknowledged that, in most cases, treatment providers responded swiftly and in accordance with company policy when faced with allegations of abuse.[30]

Broader national data further support this perspective. The National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS), a federally sponsored database, has consistently shown that residential facility and group home staff account for only 0.2% of perpetrators of child maltreatment and fatalities nationwide over the past 20 years.[31] These data provide no evidence of a growing abuse problem in residential facilities, despite widespread narratives claiming otherwise and heightened media scrutiny.

Federal data find that youth PRTFs are as safe as general hospitals, a conclusion supported by data collected through rigorous random and complaint-based surveys.[32] These surveys, conducted by state agencies and accreditation organizations, are reported to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and detailed on the QCOR website, ensuring that safety and quality standards are consistently met.[33]

While any instance of abuse is never acceptable and warrants thorough investigation, it does not appear to be the systemic issue that common narratives suggest. Proposed federal legislation aims to conduct a national study of residential treatment centers, which could provide critical data on the prevalence of abuse.[34] Until such data are available, definitive claims about widespread abuse remain unsubstantiated. In the absence of solid evidence, sweeping assertions should be approached with caution, as they risk driving misguided policies.

Seclusion and Restraint

Seclusion and restraint are practices used in youth residential treatment settings to manage situations where children pose an immediate threat to themselves or others.[35] Seclusion involves isolating a child in a room or designated area, while restraint typically refers to physically holding or restricting a child’s movement. Chemical restraint, which involves administering medication to control behavior in emergencies, is another form of intervention, though its use is banned or heavily restricted in many states.[36] Critics often argue that these practices are traumatizing, citing incidents of improper use that have resulted in harm or, on rare occasions, death.[37] However, they seldom acknowledge the harm that can occur without intervention or the lives that have been saved through the use of these measures.

SCF says that these interventions “are often used inappropriately and amount to abuse.” However, the SCF report’s appendixes show incident reports detailing their use on youth who were kicking, shoving, biting, and punching peers, nurses, and staff, banging their head on walls, attempting to hang themselves, and engaging in other forms of self-harm and violent behavior.[38]

The use of restraint has declined in recent years because of concerted efforts to reduce its frequency. Restraints are governed by organizational policies, state licensing requirements, professional guidelines from organizations such as the American Academy of Pediatrics, the Council for Children with Behavioral Disorders, the Joint Commission, and federal standards for facilities receiving Medicaid funding.[39] These guidelines uniformly state that restraints should be used only as a last resort in order to prevent significant harm to the child, other residents, or staff. Medicaid rules require strict documentation, staff training, and oversight to ensure that restraints are applied safely, appropriately, and sparingly.[40]

Treatment Deaths

Deaths resulting from improper restraint or suicides due to inadequate supervision represent tragic failures for those entrusted with the care of vulnerable children. Current data suggest that deaths in treatment are extremely rare. Government bodies, such as the U.S. Department of Justice, monitor the safety and quality of residential treatment centers for criminal-justice-involved youth. According to a recent biennial report on juvenile offenders, residential treatment centers reported four deaths in 2020: three suicides and one death of unknown cause. This equates to a rate of 5.1 deaths per 10,000 youth, or approximately 0.051%.[41]

While any death in a treatment setting is an undeniable tragedy that warrants thorough investigation and prevention, it is crucial to acknowledge that this population faces a heightened risk of mortality due to the severity of their conditions, including self-harm, aggression, and suicidal behaviors.[42] For instance, a meta-analysis found that the suicide rate among adolescents discharged from psychiatric hospitals—a group comparable with those admitted to residential treatment—is 15.8 per 10,000 person-years.[43] The ongoing decline in residential treatment options for severely at-risk youth raises concerns about potentially higher mortality rates among this vulnerable population.

Narrative 2: Residential Treatment Is Ineffective and Harmful

Critics of residential treatment frequently argue that it is ineffective, citing poor outcomes for youth who have participated in such programs.[44] However, these claims often fail to distinguish correlation from causation, as many of the challenges that they face predate their time in treatment. Research shows that outcomes are often influenced by issues that existed before treatment even began.[45]

A recent analysis examining the evidence behind claims that residential care is harmful—especially for children in the child welfare system—revealed that these conclusions were predominantly based on studies of infants and very young children raised in severely deprived social and physical environments.[46] These findings are not representative of the target population or the current residential care treatment landscape.

The question of residential treatment’s effectiveness is complicated by significant methodological challenges.[47] Determining appropriate measures of success—such as symptom reduction, educational outcomes, overall functioning, or recidivism—varies across studies. Long-term follow-up data are difficult to obtain, as outcomes are influenced by confounding variables like access to post-discharge care, family stability, and socioeconomic conditions. The ethical difficulty of conducting randomized controlled trials, which would require denying treatment to a control group, further limits rigorous research in this context. Moreover, residential treatment programs are highly diverse, differing in structure, therapeutic approaches, populations served, and quality of care, making broad generalizations about effectiveness problematic.

Research findings on residential treatment’s effectiveness are mixed, reflecting the highly individualized nature of treatment. Extensive research has shown that children and adolescents with severe emotional and behavioral disorders can benefit from residential treatment and sustain positive outcomes.[48] However, outcomes are often contingent on a youth’s level of engagement and his/her ability to participate in the therapeutic process. Youth who are motivated and actively involved in treatment typically achieve better results, whereas those who are resistant to care may show less progress.[49]

Concerns about the duration of residential treatment are frequently raised. While older models of care sometimes involved stays of a year or more, modern programs typically average three to six months, with the national average being about eight months. Research has shown that time in treatment matters: the first six months are particularly critical, correlating to significant improvements in overall functioning.[50] Shorter lengths of stay and premature discharge increase the likelihood of readmission.[51]

Much of the criticism of residential treatment comes from former patients who describe the experience as overly punitive, often because youth rarely enter these programs voluntarily. The structured nature of residential treatment, with its enforced rules, is perceived as disciplinary but is primarily designed to ensure safety. Discipline in this context is not inherently negative; it teaches youth which behaviors are unacceptable while providing clear expectations, consistent consequences, and incentives to develop self-control and manage emotional outbursts. Behavior modification programs in inpatient settings can also lower dependency on psychotropic medication for those with externalizing problems, such as aggression, impulsivity, and oppositional behaviors.[52]

Many programs use a level system, where privileges are earned by meeting behavioral goals, or step-down models that allow gradual transition to less restrictive settings. Research supports the effectiveness of these approaches, showing that the anticipation of stepping down can motivate improved behavior, with significant reductions in problem behaviors observed as youth progress within an integrated continuum of care.[53]

Critics of residential care often rely on powerful anecdotes of negative experiences, but such stories—while compelling—are inherently limited by selection bias and can be found for or against any form of care.[54] In contrast, some surveys reveal that most youth in residential care rate their experiences positively.[55]

Narrative 3: Residential Treatment Facilities Are Unregulated

Critics often claim that residential treatment programs operate without regulation. While it is true that the industry as a whole is not uniformly regulated at the federal level, this claim overlooks the oversight mechanisms already in place. Programs that accept Medicaid, such as PRTFs, must comply with federal regulations set by CMS and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).[56] These federal requirements ensure that Medicaid-funded facilities adhere to stringent standards for care, safety, and accountability.[57] However, many residential programs operate outside federal oversight and are instead regulated by state governments.

State governments are the primary regulators of residential treatment facilities, with each state implementing its own licensing and inspection requirements. Most states maintain robust systems for monitoring compliance with care standards, including regular inspections and mandatory reporting mechanisms for incidents of concern. Additionally, many facilities voluntarily seek accreditation from reputable organizations such as CARF or the Joint Commission, which impose rigorous standards and conduct regular evaluations.[58] These measures help ensure a degree of oversight across much of the sector.

Despite these existing frameworks, gaps in oversight persist, particularly for facilities operating in states with weaker regulatory systems or those that do not accept federal funding. A report from the HHS Office of Inspector General suggested that one-third of states may not collect sufficient data to effectively identify maltreatment in residential treatment programs. It further alleged that, even in states where such data are collected, monitoring practices might be inadequate.[59] While further improvements may be necessary, it is inaccurate to characterize the entire industry as unregulated, particularly given the federal and state frameworks governing many facilities.

Critics of residential care often advocate for HCBS as an alternative; yet HCBS is even less regulated. A CMS letter to state Medicaid directors cited a 2016 report commissioned by HHS, which found that “HCBS lacks any standardized set of quality measures … [and] consensus as to what HCBS quality entails.”[60] This lack of standardization highlights that the oversight challenges within HCBS may surpass those of residential care.

Narrative 4: Profit Motives Override Patient Needs

Critics of residential treatment programs contend that financial incentives in for-profit facilities can compromise patient care. However, the for-profit model is a widespread feature of the U.S. health-care system, including hospitals.[61] While for-profit residential facilities can be more costly, they often have more immediate availability and offer additional services and amenities, catering to a broader range of needs and preferences.[62]

While research specifically comparing the quality of care between for-profit and nonprofit residential treatment centers is limited, studies on inpatient psychiatric hospitals have not identified systematic differences in care quality between ownership types.[63] This suggests that similar findings may apply to residential treatment centers, indicating that ownership type might not significantly influence the quality of care in this sector. Furthermore, nonprofit facilities across the broader health-care sector face many of the same operational challenges and criticisms as for-profit facilities, making it difficult to distinguish between the two in practice.[64]

Despite its strong criticism of the for-profit model, the majority of abuse incidents that the SCF report identified occurred in nonprofit facilities. The chairman of SCF went so far as to claim that the industry “profits off taxpayer-funded child abuse.”[65] Yet residential treatment is rarely a lucrative enterprise, especially for programs reliant on state funding, which is typically provided on a fee-for-service basis.

Low reimbursement rates from government payers create substantial financial challenges for facilities. To remain operational, many programs must increase patient volumes while keeping costs low, which strains operations. Staffing costs, often the largest share of operating budgets, present a persistent challenge, as limited funding hampers the ability to offer competitive wages.[66] High staff turnover is a frequent result, as many staff find the low pay insufficient for the physically and emotionally demanding work, particularly when dealing with violent or high-needs youth.[67]

Senator Ron Wyden, chairman of SCF, has expressed his intention to “shut off the firehose of federal funding” for residential treatment.[68] However, rather than unchecked profiteering, these challenges reflect systemic funding constraints that affect the entire sector. Addressing these issues requires reforming state and local funding models to increase reimbursement rates and incentivize workforce development. These changes would help improve staff retention, elevate care quality, and ultimately lead to better outcomes for youth in residential care.

Narrative 5: HCBS Are Universally Better Alternatives

HCBS initiatives—such as counseling, family therapy, mobile crisis intervention, and school-based mental health programs—are often presented as a replacement for residential treatment. While certain forms of HCBS can effectively address mild to moderate mental health challenges, their capacity to meet the needs of youth facing acute crises, such as chronic self-harm, trauma, suicidal ideation, violent behaviors, or severe psychiatric conditions, is often limited.

Intensive home-based treatment (IHT), a form of HCBS, delivers therapeutic interventions within the home and relies on active caregiver involvement and a stable environment. Research shows that both IHT and residential treatment lead to significant improvements in psychosocial functioning and symptom severity; however, the cohorts served are fundamentally different and not directly comparable.[69] Youth accessing residential treatment typically face more severe challenges and have exhausted less intensive options such as IHT. In many cases, families managing severe behavioral issues are unable to provide the supervision necessary to ensure safety, particularly when harmful behaviors disrupt the household or endanger siblings. For these youth, residential treatment provides the structure, supervision, and intensive care necessary for stabilization and long-term recovery.

Mobile crisis intervention services (MCIS), another HCBS component, offer rapid, on-site de-escalation for youth in acute mental health crises. While MCIS can effectively stabilize youth and prevent unnecessary hospitalizations, they are not designed for long-term care. Research shows that approximately one-third of children accessing MCIS are repeat users.[70] For these youth, cycling through crises without sustained intervention hinders recovery. Residential treatment provides a structured setting where they can develop the coping strategies and self-regulation skills needed to break this cycle.

HCBS initiatives also include public-health approaches such as school-based mental health programs, which focus on prevention and early intervention through measures like screenings and social-emotional learning curricula.[71] However, research shows no evidence that universal mental health programs prevent mental illness or reduce suicide rates.[72] Poorly implemented mental health education can even cause anxiety and foster overreliance on mental health interventions for otherwise healthy children.[73]

A significant challenge in outpatient mental health treatment across all age groups is the low level of program engagement, which often results in inconsistent attendance and high dropout rates.[74] This issue also applies to families of children with mental health and behavioral issues, as caregivers may struggle to prioritize or sustain participation in treatment due to competing responsibilities or a lack of resources.[75] In residential treatment, this issue is mitigated because attendance and participation in the program are mandatory.

In its report, SCF heavily advocated for HCBS, claiming that studies demonstrate that these approaches yield better treatment outcomes and are more cost-effective than residential treatment facilities. However, the systematic review cited to support this claim did not evaluate HCBS but instead focused on behavioral health interventions in PRTFs, finding that the majority of reviewed articles noted improvements in tracked outcomes, though some results were mixed, inconclusive, or null.[76]

While some forms of HCBS are an essential part of the mental health care continuum, they are not a viable substitute for residential treatment. Residential treatment provides an important intermediate setting between more restrictive inpatient hospitalization and less intensive outpatient care, offering longer-term support that fills a critical gap. Evidence for the effectiveness of nonresidential care as an alternative to secure residential treatment for youth with severe behavioral problems or criminal behavior remains limited.[77]

Recommendations and Conclusion

Federal and state policies have significantly shaped the landscape of youth residential treatment, often creating barriers that undermine its critical role in addressing acute mental health and behavioral challenges. At the federal level, the Family First Prevention Services Act (FFPSA) of 2018 shifted funding priorities, emphasizing HCBS while restricting funding for residential care unless facilities meet strict criteria.[78] For example, the onerous regulations associated with meeting federal designation as a Qualified Residential Treatment Program (QRTP) limits the capacity for providers to assess some funding unless an extensive review is followed. These changes have reduced access to residential care for youth with acute needs by making it more difficult for facilities to qualify for funding.[79] Policymakers must recognize that HCBS and residential treatment serve distinct roles within the continuum of care, ensuring that appropriate services are available for youth across a range of needs and circumstances.

Another major federal policy affecting residential care is the Medicaid IMD Exclusion, which prohibits federal Medicaid reimbursement for psychiatric hospitals with more than 16 beds for individuals aged 21–64.[80] Although PRTFs for youth under 21 are exempt, strict compliance requirements enforced by CMS have created barriers that make it difficult for states to secure reimbursement. This has contributed to a decline in PRTFs and similar facilities, limiting access to care for youth with severe psychiatric needs. Repealing the IMD Exclusion would simplify reimbursement processes, incentivize states to maintain residential care capacity, and address unmet needs for intensive interventions.

At the state level, legislative actions often mirror federal trends while introducing additional challenges. For instance, California’s SB 1043, signed into law in 2024, mandates public reporting of seclusion and restraint incidents, even though oversight authorities already require reporting of such incidents under existing laws. This added layer of public transparency comes at a significant cost—$57.6 million over four years and $12.1 million annually—for a process that is already managed internally.[81] California’s 2021 ban on sending youth to out-of-state residential treatment programs further restricts access to specialized care that may not be available locally.[82]

States and counties are pursuing various strategies to bolster HCBS, including reallocating funds previously designated for residential care to support community-based programs.[83] These policy changes have contributed to a national emergency in youth mental health care.[84] A lack of residential treatment beds has left children inappropriately placed in hospital inpatient units or emergency rooms for extended periods.[85] In at least 18 states, foster children with severe needs have been housed in office spaces and other unsuitable environments because of the lack of residential beds.[86] While media reports briefly highlight the shortage of residential beds, they often do not address how ideological opposition to residential treatment exacerbates this crisis.[87]

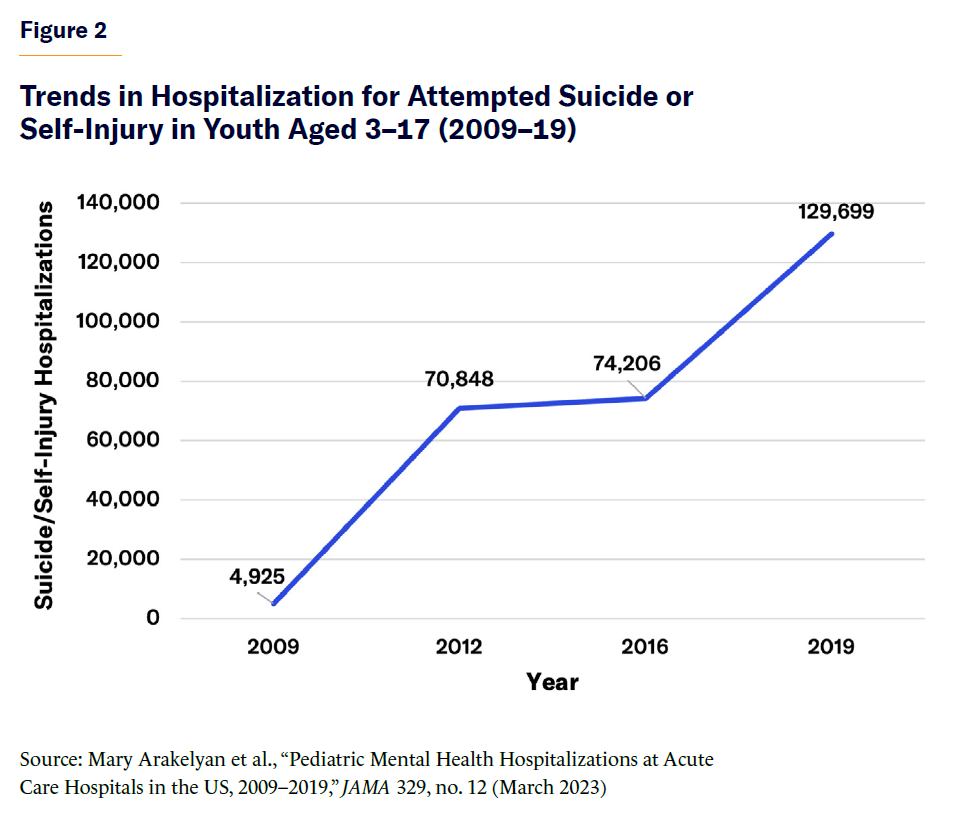

Figure 2 shows that during 2009–19, pediatric hospitalizations for attempted suicide or self-injury rose by 163.2%, underscoring the growing severity of youth mental health crises.[88]

Additionally, 26.5% of children return to emergency departments within six months of their initial mental health–related visit, and one-third of children accessing mobile crisis services are repeat users (Figure 3).[89] Research finds that youth discharged from inpatient psychiatric hospitals to lower levels of care, such as day treatment, therapeutic foster care, or group homes, are significantly more likely to be readmitted to inpatient psychiatric hospitals, compared with those discharged to residential treatment programs, which provide a higher level of care.[90]

These repeated crises highlight the limitations of short-term interventions, which stabilize youth temporarily but fail to address underlying issues. Residential treatment, which provides long-term care, is uniquely positioned to break this cycle by offering consistent support for stabilization, coping skill development, and self-control. The near 50% rise in completed suicides among individuals under 18 over the past decade further underscores the need for secure residential care, which can provide the supervision and intervention necessary to prevent such tragedies.[91]

To improve the landscape of youth residential treatment, policymakers should prioritize practical reforms rather than reduce access or discourage its use. Distinguishing between high-quality residential facilities and those with deficiencies is essential. Well-run residential programs remain vital for youth with severe, recurring mental health challenges. Establishing services to help families identify safe, high-quality residential treatment programs would empower parents to make informed decisions and reduce reliance on problematic facilities.

The proposed federal Stop Institutional Child Abuse Act aims to conduct a national study on youth residential treatment. While collecting national data could help identify problem facilities and areas for improvement, much of the discourse surrounding this bill frames residential treatment as inherently abusive, unfairly stigmatizing the entire sector based on isolated incidents. This framing risks deterring families from seeking necessary care for their children and discourages policymakers from supporting an essential component of the mental health care continuum.

Activists often emphasize “lived experience” narratives, but policymakers must include a diverse range of perspectives, including from families and individuals who feel that they benefited from treatment. Journalists also have a responsibility to balance reporting and present a more accurate picture of the sector. By addressing valid concerns while supporting residential care, policymakers can preserve this critical resource for at-risk youth. Reforms must ensure that residential care is safe, effective, and accessible for families navigating complex mental health and behavioral challenges.

About the Author

Christina Buttons is an investigative reporter at the Manhattan Institute. Her work focuses on a range of social issues, including pediatric gender medicine, child welfare policies, youth mental health treatment, and immigration.

Previously, Buttons worked as an independent journalist, maintaining her Substack, buttonslives.news. She is a regular contributor to City Journal, and her work has appeared in publications such as Quillette and Reality’s Last Stand. Buttons also served as an investigative reporter for The Daily Wire, covering the sex and gender beat.

Buttons has conducted research on the connection between autism and gender dysphoria at Environmental Progress and presented her study of de-transitioners at the 2023 Genspect Bigger Picture conference. Her expertise has led to appearances on popular podcasts such as Triggernometry, Gender: A Wider Lens, and Heretics. She occasionally cohosts a livestream show, Conversations with Peter Boghossian.

As an investigative journalist, Buttons is known for her thorough research and clear reporting on complex and often controversial topics. She is based in Nashville, Tennessee.

Endnotes

Photo: Elva Etienne / Moment via Getty Images

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).