The Jobs–Housing Mismatch: What It Means for U.S. Metropolitan Areas

Many American metropolitan areas exhibited robust job growth in the favorable economic conditions that prevailed for most of the past decade, up to the pandemic-induced recession of 2020. However, not all those metros matched job growth with housing growth. Largely because of restrictions on land use, some of the nation’s most successful and productive metropolitan areas failed to meet housing demand. The populations of those areas became better educated and earned higher incomes. Even though many jobs that don’t typically require a college education paid better in those metros, less-educated workers gravitated to the growing metros where housing was more affordable. When high-wage, high-productivity metros exclude many of the workers who would want to work there—but can’t find housing that meets their needs and that they can afford—the national economy grows less than it could have.

Growing U.S. metros that better matched housing supply with job growth often relied on widespread construction of single-family homes on previously undeveloped land. This sprawling development pattern leads to automobile dependence and traffic congestion, threatening future growth as lower-priced housing becomes ever more distant from employment concentrations. The most impressive areas successfully achieved both density and plentiful supply. These metros are best positioned for the future.

Many of the successful metros are struggling to shift housing patterns to permit higher density, and all want to increase the use of public transit. The federal government can play a constructive role in helping U.S. metropolitan areas transition to higher densities and more transit use with financial aid for planning, housing assistance, and public transit. However, such spending has often been wasteful in the past, and constant vigilance is required to ensure that new spending is cost-effective. Some commentators have also suggested that the federal government, by withholding or conditioning aid, can force resistant communities to liberalize zoning and become more open to denser and more affordable types of housing. Such hopes seem unrealistic, given the federal government’s lack of authority and expertise in land-use regulation. As the deleterious effects of the jobs–housing mismatch become clearer, actions are increasingly being taken at the state and local levels to lift the many regulatory impediments that stop new housing from being built where it’s needed.

Introduction

This report examines the “jobs–housing mismatch” across U.S. metropolitan areas from peak to peak in the last economic cycle (2008–19). The mismatch refers to a trend in which, over a period of time, large numbers of jobs—but relatively few housing units—are created. Defined in this way, the jobs–housing mismatch is commonly associated with metropolitan areas that exhibit a high degree of regulation of new housing construction. Restrictive regulation, combined with strong labor demand, leads to tight housing markets, as new workers are attracted to a growing metropolitan area but unable to find housing that meets their needs and that they can afford. A 2005 Federal Reserve Board paper by Raven E. Saks found that, as a result, housing is more expensive while employment growth is lower than it would be in a less regulated area. The composition of the labor force changes as well, as people who move into the area tend to have higher incomes, and lower-income workers are impelled to move out of the area.[1]

The urban-planning and economics literature includes many more references to a different kind of jobs–housing mismatch. Within growing metropolitan areas, job growth is often focused on areas distant from locations where lower-cost housing is available. A 1989 article by Robert Cevero in the American Planning Association’s APA Journal found such imbalance—between growing suburbs and older central cities where low-cost housing is located—to be a major cause of increasing traffic congestion in growing metropolitan regions. He attributed the imbalance to several factors: “fiscal” and “exclusionary” zoning, growth moratoriums, a resulting mismatch between worker earnings and the cost of available housing, and the growth of two-earner households and increased job mobility.[2]

More recently, an Urban Institute study, using data from an online job-matching service for low-wage service jobs, found a widespread mismatch between job locations and where workers live. However, this is no longer simply a matter of suburban growth; in some cases, traditional core cities have resumed their traditional role as job centers but have not allowed their housing stock to grow to meet demand, resulting in low-wage service job-seekers being relegated to residences in outlying areas.[3] Among the strategies to overcome current jobs–housing mismatches within regions, according to the study, are increased opportunities for promotions and pay rises so that workers have an incentive to travel long distances for jobs, creating housing near public transit, and improving access to public transit.

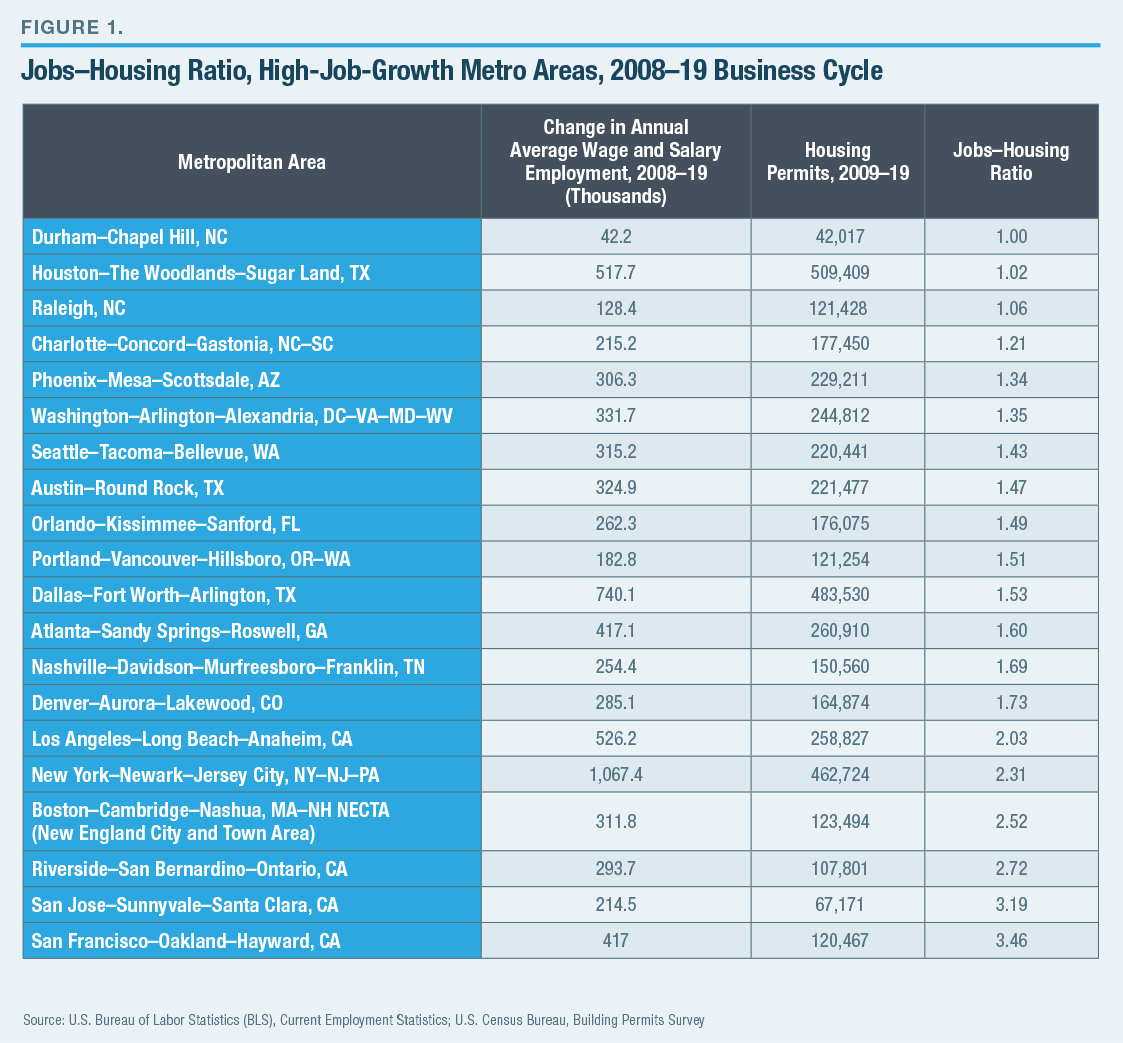

This report looks at a sample of U.S. metros that exhibited high job growth from November 2009 to November 2019.[4] Metro areas are defined by the U.S. Office of Management and Budget as including a central county and may include additional counties (in New England, municipalities) based on commuting patterns. In some cases, as in the San Francisco Bay Area (San Francisco and San Jose) and the Research Triangle area of North Carolina (Raleigh and Durham–Chapel Hill), the government’s definitions create adjacent metro areas that are commonly viewed as a single entity. Metros are ranked based on the ratio of new jobs to housing permits (Figure 1).

The higher the ratio, the greater the imbalance between job growth and housing construction in the period. Unsurprisingly, some of the nation’s most expensive metros cluster at the bottom of the chart: Los Angeles–Long Beach–Anaheim, New York–Newark–Jersey City, Boston–Cambridge–Nashua, San Jose–Sunnyvale– Santa Clara, and San Francisco–Oakland–Hayward. These were identified by Saks in 2005 as among the nation’s 20 most regulated metropolitan areas, along with Riverside–San Bernardino–Ontario, a lower-cost but also lower-wage area. Many of the metros grouped at the top of the list in Figure 1 were ranked much lower on Saks’s regulation metric.[5] The regulation metric was clearly predictive of a jobs–housing imbalance over the subsequent economic cycle.

This paper considers how this imbalance influences the distribution of different types of employment among the nation’s metropolitan areas. As Saks predicted, the labor force in the metros with a high mismatch between jobs and housing production over time becomes tilted toward occupations that typically pay well enough for workers to afford elevated housing costs. The share of workers in lower-paid occupations falls, as well as the less-educated workers who fill those jobs, and the industries that need large numbers of such worker gravitate toward the metropolitan areas where housing construction keeps pace with job growth—and thus housing is more affordable to workers at a range of incomes.

The nation pays an economic price for this redistribution of labor.[6] If the high-mismatch metros were more open to building housing, less-educated workers would be more likely to be able to take advantage of job opportunities in these areas providing services to high-productivity businesses. These jobs would, on average, pay higher wages than similar jobs in more affordable metros. The lost output from these jobs not taken is a significant loss to the national economy.[7]

The metropolitan areas where the economy is tilting toward higher-paying jobs that require a college degree, and away from those that are usually filled by people who are not college graduates, also tend to be areas with a larger share of the workforce using public transit to reach their place of work. Public transit is inherently an egalitarian institution, knitting metropolitan areas together as unified labor markets without necessitating the cost of owning a car. However, in areas where housing production fails to keep pace with employment growth, proximity to public transit confers a cost premium on the limited supply of existing housing. Housing that is affordable to lower-paid workers is found, at best, in outlying areas, resulting in long commutes. In contrast, metros where housing is more widely affordable tend to have much more limited public transit options, which are little used. The vast majority of workers commute by private vehicles.

Sprawling regions tailored to cars are difficult to retrofit for less driving and increased transit use, although some communities within growing metropolitan areas are trying. Local efforts to expand public transit are difficult because these areas have a sprawling land-use pattern not well suited to public transit service and because public support is hard to mobilize for what is currently a little-used service. This, in turn, will ultimately exacerbate traffic congestion and pose a threat to continued job growth as businesses are less able to attract the workers they need.

The twin challenges of urban sustainability—moving people to transit where it exists, and transit to people where it does not—are daunting in a nation where the federal government has little influence over land use and has not been effective in using its role in funding local transit to force efficiencies in design and construction. Recent commentaries suggest a far more interventionist role for the federal government in urban land use than has been heretofore contemplated. Such intervention could be deeply unpopular in the high-mismatch metropolitan areas.

While the Biden administration proposes a federal role in promoting local zoning reform, the administration’s proposals have stopped short of coercing compliance with more permissive standards. An aggressive stance limiting local governments’ ability to restrict new housing is more likely to be taken by state governments in response to organizing and persuasion by advocacy groups.

The Biden administration has also proposed a large increase in federal aid for local transit modernization and construction. As of spring 2021, whether Congress will ultimately approve such aid or impose conditions to address spiraling construction costs is not yet clear.

Comparing Metropolitan Areas with Different Levels of Jobs–Housing Balance

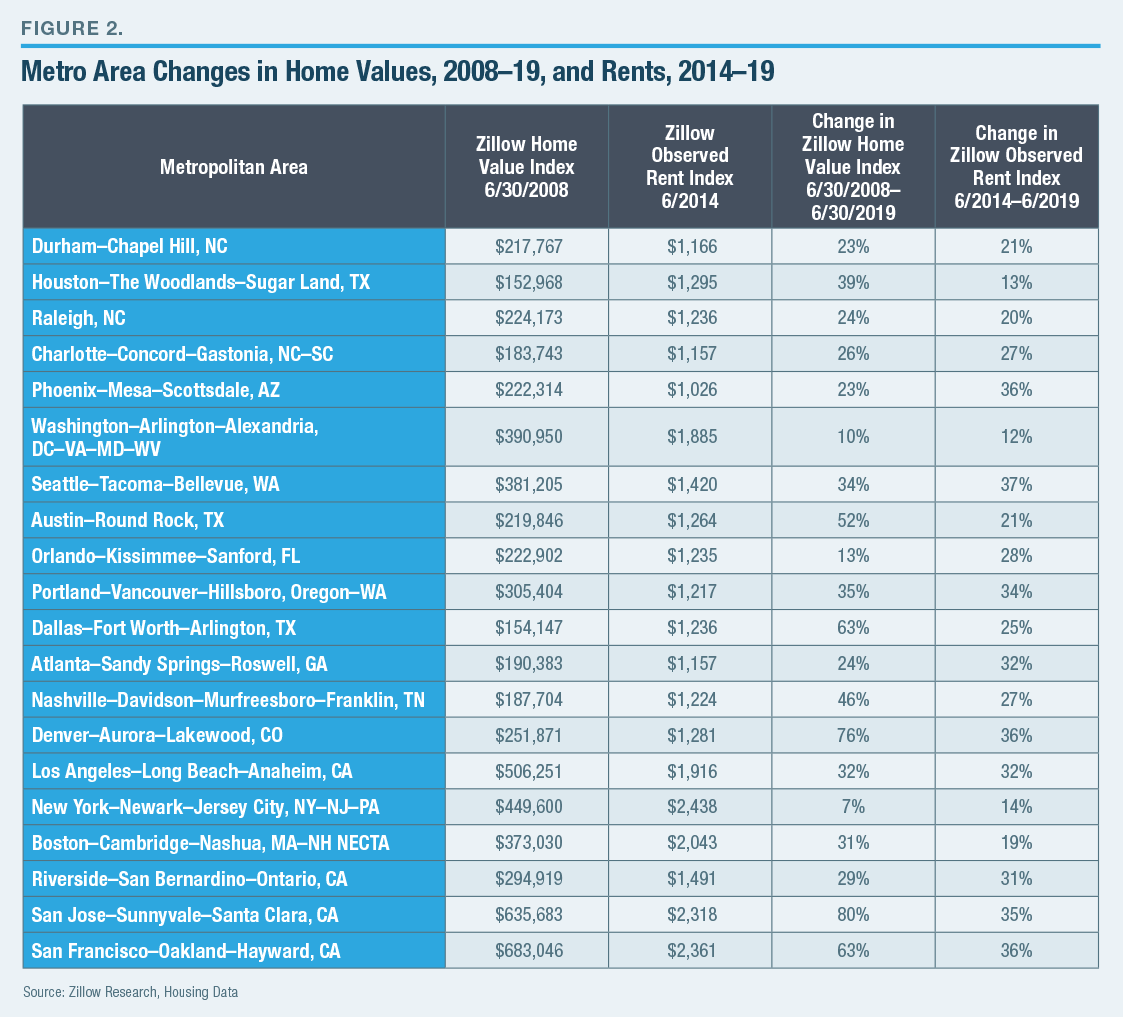

A comparison of different indicators for the metros in this study provides insight into the implications of matching job growth with housing growth or failing to do so. Changes in home values and rents do not follow a consistent pattern (Figure 2). It is likely that home values at the beginning of the period were influenced by the number of units constructed in the previous period, as well as market conditions in 2008. Thus, the changes over a more recent period (2008–19) were also influenced by these initial conditions. The Zillow Observed Rent Index data began in 2014 and also show an inconsistent pattern. The highest- percentage rent increases are in the “mismatched” San Francisco Bay metro but also in the better-matched Phoenix–Mesa–Scottsdale metro, where rent increases outpaced changes in home values.

Rising sales prices and rents may indicate that incomes are rising, or that housing is becoming relatively more scarce. In the latter case, “cost burdens” would rise for households at progressively higher levels of income. (Cost burden refers to households that pay more than 30% of their income in rent.) All the metropolitan areas in this study had affordability issues in 2019 for households with very low incomes (Figure 3). For most of the “well-matched” metros, the cost burden for households with incomes of $20,000–$35,000 is rising. However, because the comparison is in nominal, not constant, dollars, this may be partly because this population category is relatively poorer in 2019 than in 2014. The cost burden is perhaps lower in some cases for households with incomes under $20,000, due to greater access to subsidized housing.

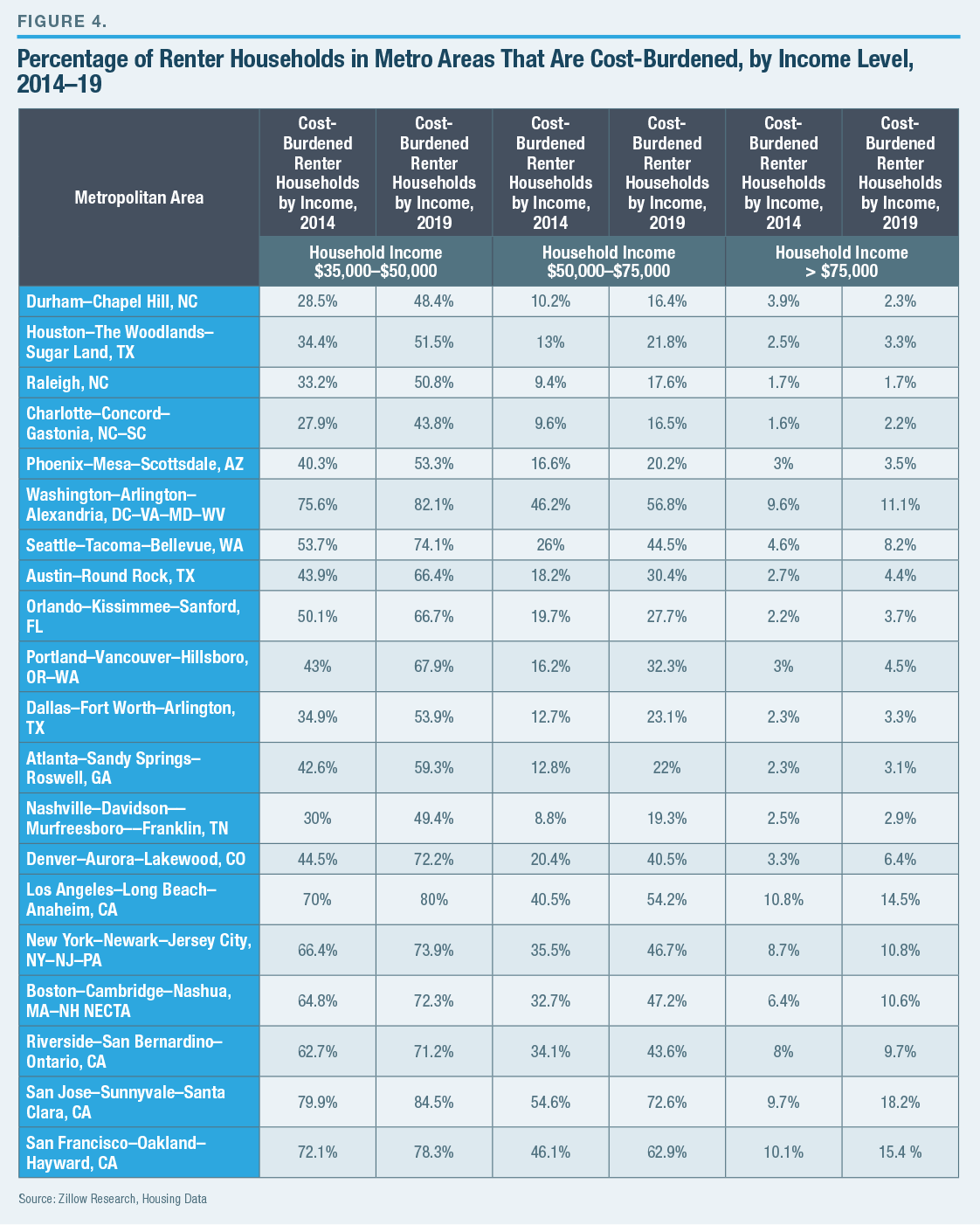

What distinguishes metropolitan areas that have successfully matched job growth with housing from those that have not is a generally lower level of cost burden for households in the $35,000–$50,000 range. Several metros have kept the cost burden for this group in 2019 down to the range of about 50% (Charlotte–Concord–Gastonia, North Carolina–South Carolina is the lowest, at 43.8%, Figure 4). In contrast, the seven metros at the bottom of the table all have a cost burden for this income group in excess of 70%.

The pattern is even more pronounced for cost-burdened households in the $50,000–$75,000 income range, where several of the better-matched metros had cost-burden levels for 2019 in the 20% range (Durham–Chapel Hill is the lowest, at 16.4%). The bottom seven metros all have cost burdens in this income range over 40%, with San Jose–Sunnyvale–Santa Clara, California, by far the highest, at 72.6%. The cost burden was generally low for households with incomes over $75,000.

As housing becomes relatively costlier, high-growth, “mismatched” metros gravitate toward high-value-added activities that attract better-paid employees who can afford housing in a supply-constrained market. This results in growth in per-capita personal income above the national average.[8] Nationally, per-capita personal income grew by 38% during 2008–19, compared with consumer price inflation of about 17% (Figure 5). Many of the “well-matched” metros have per-capita personal income growth below the national average, as their economies are more likely to retain low-productivity workers and low-value-added activities. Charlotte–Concord–Gastonia had no growth in real per-capita personal income. Most of the more “mismatched” metros at the bottom of the table had per-capita personal income growth well in excess of the national average, with the San Francisco–Oakland–Hayward metropolitan area having the largest growth.

Blue-collar workers likely are more productive in the “mismatch” metros because the services they support are higher-value-added. Thus, they receive a wage premium above the national average. This wage premium is consumed, however, by higher housing costs. Figure 6 looks at three major occupation categories that do not typically require a college degree. In most of the “better-matched” metros, the median hourly wage in 2019 was at, or slightly below, the national average for office and administrative support; construction and extraction; and installation, maintenance, and repair occupations. In contrast, in many of the “mismatched” metros at the bottom of the table, the median wage was well above the national average.

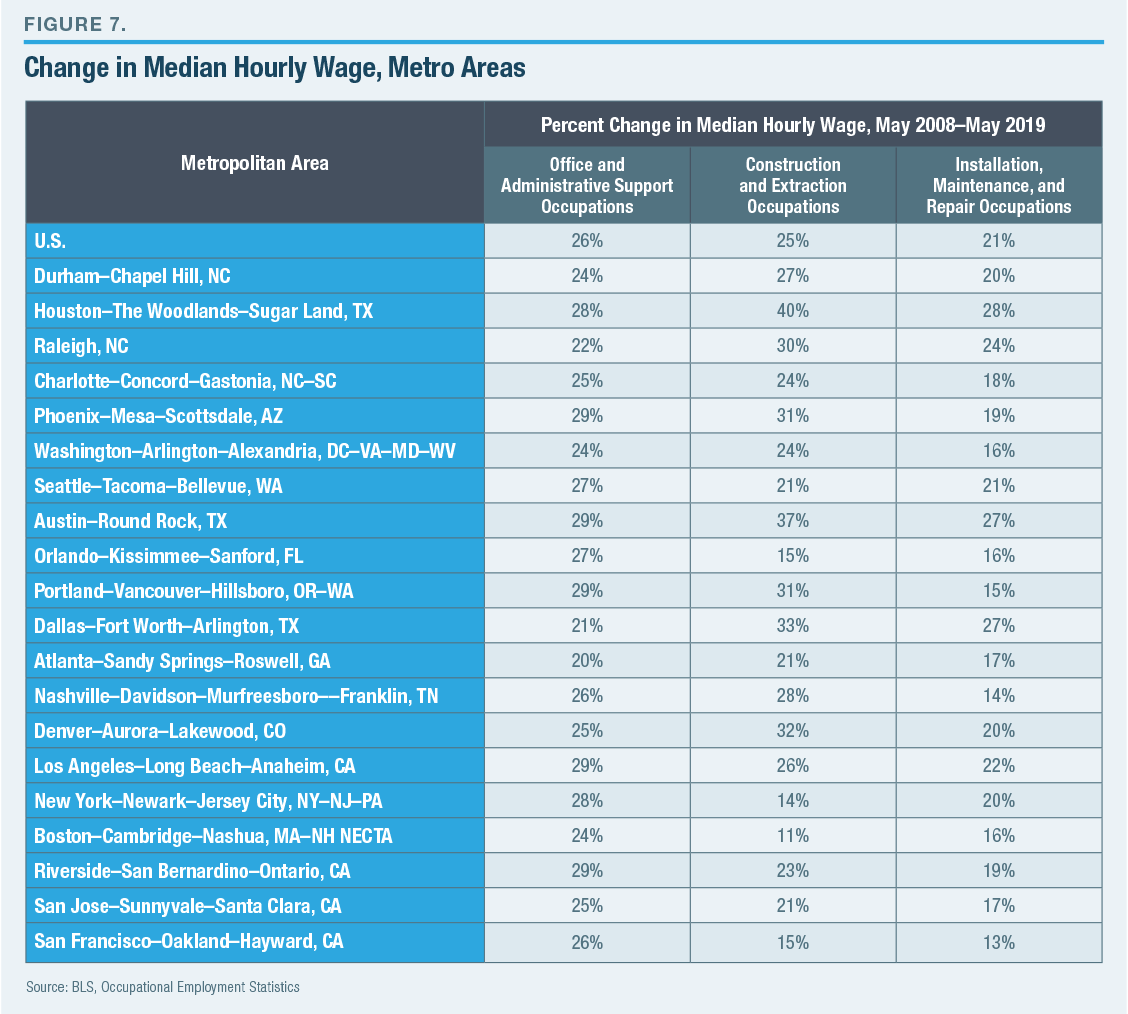

However, wage increases were close to the national average in all metros for office and administrative support occupations (Figure 7). Wage increases were higher than the national average in some “well-matched” metros for construction and extraction occupations, as well as installation, maintenance, and repair occupations. Texas metros (Houston–The Woodlands–Sugar Land, Austin–Round Rock, and Dallas–Fort Worth–Arlington) led the group. The higher wage increases made these metros relatively more attractive to these types of blue-collar workers, even though wages remained higher in the “mismatched” metros.

There were large jumps in the percentage of the population over age 25 who are college graduates for all metro areas between 2010 and 2019 (Appendix A). However, there is a group of generally better-matched metros that have retained a higher percentage of non-college graduates. For example, Houston–The Woodlands–Sugar Land had 33.3% college graduates in this age group, while Phoenix–Mesa–Scottsdale had 32.2%. In contrast, many “mismatched” metros had 40% or more college graduates. “Jobs–housing mismatch” implies a squeeze on non-college workers and a rising share of college graduates who can get jobs that enable them to afford the housing cost premium.

The data also indicate the existence of metros that might be viewed as highly attractive for college graduates—where they can enjoy the wage premium that comes with education but not see that premium eaten away by housing costs. Raleigh and Durham–Chapel Hill stand out in this category, but others likely include Seattle–Tacoma–Bellevue and Austin–Round Rock. Washington–Arlington–Alexandria has historically been a high-cost area, but its good housing performance in the last economic cycle presages greater competitiveness in the future.

Only five of the metropolitan areas included in this study had as many as 10% of commuters using public transit as the primary means of commuting to work in 2019 (Figure 8). All are areas with a high percentage of college graduates, and three (New York–Newark–Jersey City, Boston–Cambridge–Nashua, and San Francisco–Oakland–Hayward) are at the bottom of the table, indicating a high degree of mismatch between job growth and housing construction.

Many areas where housing construction is better matched to job growth have limited public transit and transit commuting shares as low as 1%. Correspondingly, driving-alone percentages for commuting in these areas are in the 80% range.

This contrast raises the issue of the second type of jobs–housing mismatch—the one that persists within metropolitan areas, where jobs are often not being added in the same areas where relatively affordable housing is available. This type of mismatch is an inconvenience but not an insuperable obstacle to employment in metros with good transit; lower-wage workers whose choices of residence are limited geographically by affordability can still get to many jobs without owning a car. In metropolitan areas where transit is limited, not owning a car is a real impediment to finding work.

Even where workers have access to a car, congestion deters long commutes. Many of the nation’s fastestgrowing metros in terms of employment ranked high in traffic congestion measures in the pre-pandemic period. For example, most of the metropolitan areas with a public transit commuting share below 10% (Atlanta–Sandy Springs–Roswell, Houston–The Woodlands–Sugar Land, Dallas–Fort Worth–Arlington, Phoenix–Mesa–Scottsdale, San Jose–Sunnydale–Santa Clara, Riverside–San Bernardino–Santa Clara, Austin– Round Rock, Portland–Vancouver–Hillsboro, and Denver–Aurora), had 61 hours or more of yearly delay per auto commuter, placing them in the top 20 for all U.S. metropolitan areas.[9]

Examining the Better- Performing Metro Areas

Raleigh–Durham–Chapel Hill, North Carolina

As shown in Figure 9, new housing permits in Wake County, the area including Raleigh that is at the center of the last decade’s growth, were dominated by land-intensive single-family homes. Moreover, the single-family construction was widespread, not only in the central city of Raleigh but in other communities such as Apex and Cary. Only in Raleigh itself did the construction of buildings of five or more units predominate.

Major employers have noticed the Raleigh area’s success in matching job growth with new housing, creating a desirable environment for new workers. In April 2021, for example, Apple announced that it would invest over $1 billion in a research and engineering campus in Wake County’s Research Triangle Park, creating at least 3,000 new jobs.[10]

Continued growth in this area will require a different model from the past decade, as open land is less readily available for development. The new model will need to favor denser development, which has not been common outside Raleigh. Also in April 2021, in a context of rising home prices and concerns about stagnating construction levels,[11] the Wake County Board of Commissioners adopted PLANWake,[12] a growth framework for the next decade. The plan would focus mid- and high-rise multifamily developments along bus transit corridors, mostly within Raleigh, and lower-scale multifamily housing along more widespread “walkable center” areas representing about 10% of the county’s land.[13] ”Walkable centers” are communities dense enough so that some services and activities can be accessed by residents on foot. Achieving this vision will require the cooperation of local governments, as well as considerable investments in public transit and water and sewer infrastructure. If municipalities instead continue to approve mostly sprawling single-family-home developments, the Raleigh area could find itself experiencing the combination of high housing prices and congested roads familiar to residents of the high jobs–housing “mismatch” metros.

Concurrently in the spring of 2021, the North Carolina legislature is considering changes to state law that would make this outcome less likely. The “Act to Increase Housing Opportunities” (Senate Bill 349 and House Bill 401) would require municipalities to allow new homes to have up to four units on a lot where water and sewers are provided, as well as attached homes and “accessory dwelling units” (second units on existing single-family lots).[14] The legislation offers an alternative mechanism for meeting, at least in part, housing demand in growing areas such as Raleigh, should communities fall short on goals for new apartment dwellings in denser, transit-oriented communities.

Austin–Round Rock, Texas

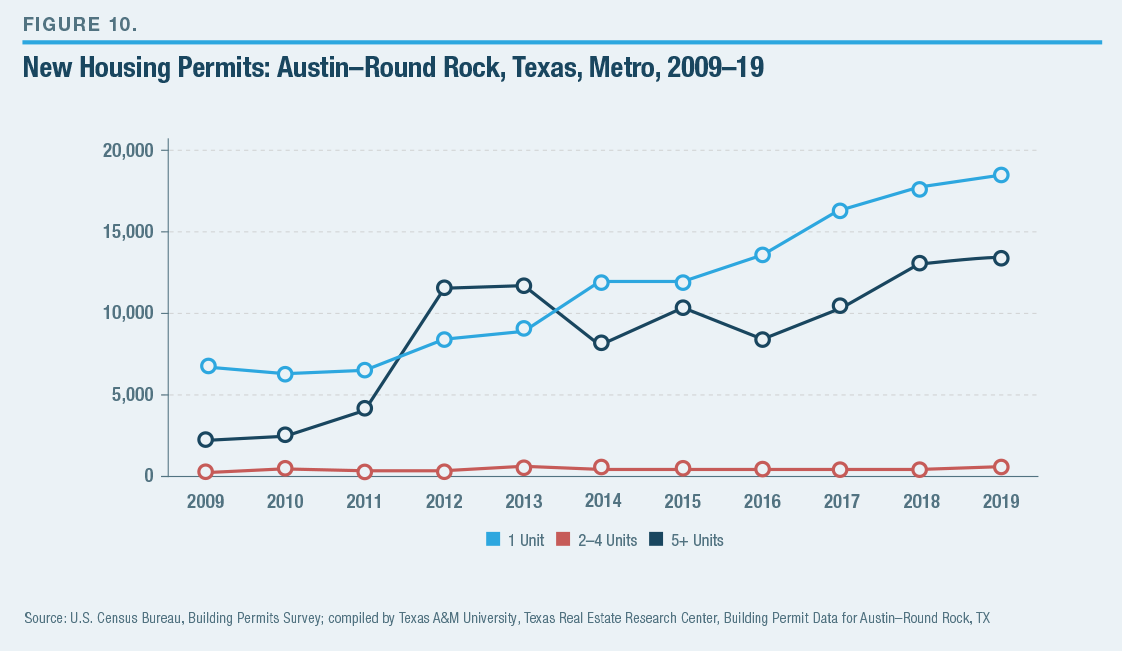

In contrast to the Raleigh area, new housing permits in the Austin–Round Rock metro during 2009–19 were better balanced between single-family homes and buildings with five or more units. This was particularly true in Travis County, the most populous in the region, where Austin is located. In Travis County, permits for buildings of five or more units consistently outpaced single-family homes on an annual basis (Figure 10).

Austin has also been successful in attracting major investments from tech companies, and, compared with Raleigh, the conditions that attracted those companies are threatened by the region’s very success. As of early 2021, median home prices were up sharply year-over-year and had reached record levels.[15] However, the housing construction market was highly responsive. New housing permits were also up sharply in the region in 2020, including more than 23,000 permits for single-family homes and more than 19,000 units in buildings with more than five units.[16]

The region’s established practice of using land more intensively,[17] combined with the rapid run-up in permits, augurs well for the region’s ability to continue growing while maintaining housing affordability at a range of incomes. However, efforts to amend zoning to permit denser buildings in central Austin have run into political opposition.[18]

As in the Raleigh area, planners are seeking so-called smart growth—relatively dense multifamily housing with amenities that can be reached by walking and public transit to reach workplaces. The alternative, as communities become more resistant to land-use change, is continued single-family sprawl to the edges of the region. As the region’s traffic becomes more congested and commute times increase, first-time home buyers must live farther from job concentrations to find affordable homes, and the region’s attractiveness to many employers may diminish.

Houston–The Woodlands–Sugar Land, Texas

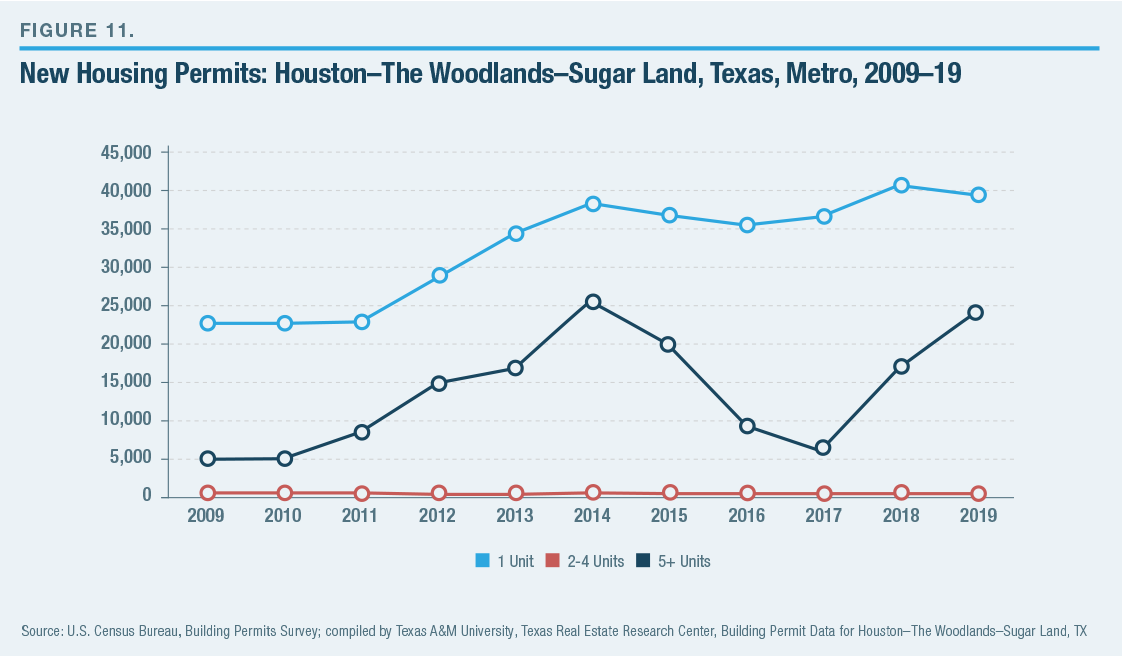

Despite Houston’s reputation as a city with no zoning[19] and loose controls on land use, the greater Houston area relied during 2009–19 more on single-family home construction than did the Austin area (Figure 11). As in Austin–Round Rock, the market has responded strongly to the rising demand for homes,[20] but in the Houston area, this response is more concentrated in single-family construction. In 2020, single-family permits increased from about 39,500 to more than 50,000, while permits for new units in buildings with five or more units decreased from about 23,800 to 20,300. The Houston-area development pattern makes the further expansion of the already vast-developed metro area likely. Commutes will be longer and job markets more fragmented.

In the Houston metro, mass transit is limited to Harris County, where the city of Houston is located. In 2019, Harris County voters approved a $3.5 billion bond issue.[21] Plans include the expansion of light rail lines, new bus rapid transit service, enhancements to existing high-ridership bus routes, and new and improved high-occupancy vehicle (HOV) lanes on major highways.[22] While valuable, the improvements are hardly on a scale to alter the region’s dependence on single-occupancy-vehicle commutes.

Seattle, Washington

The Seattle region has achieved a distinction that Raleigh, Austin, and Houston cannot: in the last economic upturn, it performed well in matching new housing permits to new jobs while predominantly producing housing in buildings of five or more units (Figure 12). The Seattle area also produced a significant number of units in the two- to four-unit range, often a source of lower-rent unsubsidized housing.

In 2019, the Seattle City Council approved an “upzoning” plan allowing denser buildings in 27 neighborhoods, many of which are connected by existing or proposed light rail transit.[23] The plan increased permitted densities on lots where apartment buildings were already allowed. However, developers would be required to devote 5%–11% of the building to affordable housing or pay a fee in lieu of providing affordable housing. While proponents asserted that the affordability requirements would result in the construction of up to 3,000 affordable apartments across Seattle over 10 years, this depends on whether developers continue to view new housing construction as generating an adequate return on investment.

In early 2021, the regional transit agency, Sound Transit, which initiated an ambitious regional light rail expansion plan in 2016, was beset by financial shortfalls.[24] As housing becomes costlier to build in the urban core and transit expansions are cut back or delayed, the Seattle area may find keeping the pace of housing growth in line with job growth increasingly difficult.

Conclusions

The data on the jobs–housing mismatch and its effects in metropolitan areas illustrate how the U.S. economy is subject to an odd kind of central planning—one that exists without a central planning authority or even intent. It is, instead, the result of decisions made, often long ago, to adopt permissive or restrictive land-use regulatory frameworks and to distribute political power at the state and local levels. Specific metropolitan areas have institutional arrangements that empower opponents of growth. These arrangements add up to a long list, including municipal fragmentation, local control of land use, multiyear review processes for zoning changes or conditional-use permits, historic preservation, and environmental review. Other metro areas are preempted by states from enacting roadblocks to growth or have benefited from pro-growth leadership, at least in the recent past. Still other areas have relatively permissive regulatory arrangements that favor new housing development. These local quirks strongly influence the types and levels of economic activity in different metro areas and, therefore, the size and composition of the U.S. economy, since most economic activity takes place in metropolitan areas.

In a recent blog post, commentator Will Wilkinson notes the importance to national economic growth of the high mobility of workers from one part of the country to another.[25] This ensures that when different regions grow at different rates, a growing region is not subject to labor shortages and rising price inflation, while a declining region does not experience mass unemployment. Without labor mobility, political tensions emerge as some parts of the currency area prosper and others stagnate.

Wilkinson suggests that restrictive zoning in some parts of the country has become an impediment to labor mobility and thus to the functioning of the American economy. He cites Yale law professor David Schleicher, who wrote in 2017 that “lower-skilled workers are not moving to high-wage cities and regions…. [S]tate and local (and a few federal) laws and policies have created substantial barriers to interstate mobility, particularly for lower-income Americans.”[26]

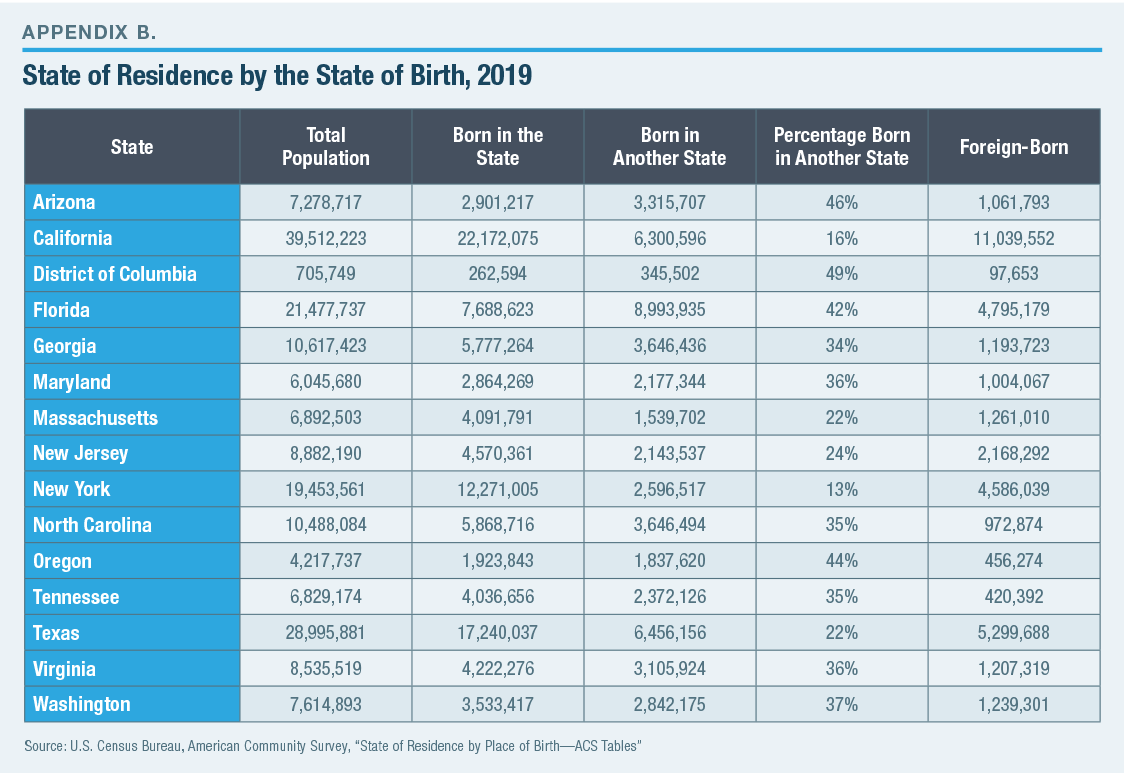

Recent census bureau data from 2019 are available on the place of birth of state residents. Appendix B provides information on the states in which the high-job-growth metropolitan areas considered in this report are located. In many states, the percentage of the population born in another state is within a narrow range in the mid-30s (Georgia, Maryland, North Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, and Washington State). Arizona and Florida, with their large retiree populations, are high outliers, at 46% and 42%, respectively. The low outliers, with few residents born in other states, are mainly the states where housing construction in major metros is out of balance with job growth, deterring interstate mobility: California (16%), Massachusetts (22%), New Jersey (24%), and New York (13%). Interestingly, Texas, which grows with a high rate of natural increase (births minus deaths), also has a low percentage of residents born out of state (22%).[27]

Some, but not all, of the difference between the stagnating states and those attracting large numbers of native-born migrants is explained by higher foreign immigration. New York, for example, had 24% foreign-born, compared with 16% in Washington State. However, for New York to have enough in-migrants (foreign-born and native-born) to bring the population percentage born in-state (63% in 2019) to the level of Washington State (46%), its population would be 26.7 million, not 19.5 million.

Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, and California are third through sixth among states in terms of income per capita, so workers would likely want to move to them to secure higher wages, were housing scarcity and costs not such a deterrent.[28] Wilkinson cites a 2017 paper by Kyle F. Herkenhoff, Lee E. Ohanian, and Edward C. Prescott,[29] in which the authors conclude:

However, even the regions that facilitate housing growth are highly dependent on the development of single-family homes—mostly on previously undeveloped land—and the construction of highways to enable mostly single-occupant vehicles to commute to work. Making cities and suburbs denser as an alternative to peripheral sprawl depends on public buy-in to higher density and transit construction that becomes more difficult over time, even in pro-growth areas.

All the more reason, perhaps, for the federal government to maximize pressure on high-opportunity metros that have extensive existing public transit infrastructure to cure their imbalance between job creation and housing production. Many proposals exist in which the federal government would encourage, but not force, change. The HOME Act,[31] proposed by Senator Cory Booker and Representative James Clyburn, would require states receiving Community Development Block Grants (CDBGs) or Surface Transportation Block Grants to create an “inclusive zoning strategy.” This strategy could include a variety of measures, such as reducing required lot sizes, eliminating parking requirements, or allowing accessory dwelling units and multifamily housing. Biden’s 2020 campaign endorsed the proposal, prompting vehement attacks from incumbent Donald Trump, who charged that this mild effort at reform would “abolish the suburbs.”[32] Wealthy suburban communities that did not want to create the required zoning strategy, however, could forgo this federal funding.

The Yes in My Backyard (YIMBY) Act,[33] passed by the House, but not the Senate, in 2020, would require CDBG recipients to submit a report every five years explaining whether they have implemented specific zoning practices that increase housing opportunities for low- and middle-income households. If they have not adopted these practices, the report would explain whether they intend to and, if not, why not.

The Housing Supply and Affordability Act, introduced by Senators Amy Klobuchar, Rob Portman, and Tim Kaine, provides $300 million annually in planning and implementation grants to encourage states and localities to remove regulatory barriers to housing construction.[34] Biden’s American Jobs Plan proposes a $5 billion fund for localities to compete for grants to build new infrastructure if they have taken steps to remove regulatory barriers to new housing.[35]

Biden’s current approach has been criticized for being all “carrot” with no “stick.” The idea for the “stick,” according to one commentator, “is pretty straightforward: Rather than just telling states and localities they can get access to an extra pot of money if they choose to reform, tell them they’ll miss out on a much bigger pot, and one they may routinely count on, if they don’t.”[36]

In this vein, Harvard economist Edward Glaeser suggests that American Jobs Plan infrastructure funds be withheld from “states that fail to make verifiable progress enabling housing construction in their high-wage, high-opportunity areas.”[37] Similarly, a 2020 proposal by Solomon Greene[38] of the Urban Institute and Ingrid Gould Ellen of New York University’s Furman Center would condition states’ eligibility for competitive federal funding for housing, transportation, and infrastructure on demonstrable progress toward housing production and affordability goals. The authors propose that any state that both eliminates single-family zoning and institutes an appeal mechanism for mixed-income developments in communities that lack affordable housing currently be presumed to be advancing such goals and thus automatically qualified for funding.

It’s implausible that a Democratic administration would take such punitive actions against what are, in many cases, very safe Democratic-supporting states in national elections. A version of the Biden plan, with carrots but no sticks for zoning reform, seems more plausible to pass Congress than the more punitive alternatives.

One important contribution that the federal government can make is to help willing communities become denser and transit-oriented, as many want to do, including in pro-growth states characterized by sprawling metropolitan areas composed mainly of single-family homes. This requires a combination of planning assistance, transit infrastructure spending, and affordable housing funding. Even big cities rarely have the resources to do this on their own. Elements of various proposals address these issues, including the Housing Supply and Affordability Act and the American Jobs Plan, which includes a proposed $85 billion for public transit and $213 billion for housing assistance.[39] To be credible, however, an enlarged transit program needs to be able to avoid the inefficient procurement, cost overruns, and poor design choices experienced in Seattle and common in U.S. transit construction.[40] Housing assistance to households in the income categories troubled by cost burden is necessary to achieve public buy-in for denser zoning in many cities. However, it needs to be cost-effective and not repeat the errors of past federal housing programs that (like public housing) made affordability commitments that couldn’t be sustained on a shaky base of annual congressional appropriations, or (like Section 8 new construction of the 1970s) committed so much funding per unit up-front that few households could be served.

The best hope for changing zoning practices that result in a jobs–housing mismatch is organizing at the local level and in state capitals where legislatures are increasingly inclined to set limits on local governments’ discretion to prohibit new housing as public attitudes evolve.[41] The problems created by rapid growth create the conditions for antigrowth politics. However, the deleterious consequences of antigrowth politics, combined with generational changes in lifestyle preferences, perhaps create the political conditions for pro-denser housing and pro-transit reforms.[42] An enlightened federal government has a role in spurring such changes and funding the improvements that make them possible. Nevertheless, metropolitan areas will ultimately become more urban and less car-oriented if the voters in those areas and the states that depend on them for tax revenue are convinced that it is a good way to live.

Appendix

Endnotes

About the Author

Eric Kober is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute. He retired in 2017 as director of housing, economic and infrastructure planning at the New York City Department of City Planning. Kober was visiting scholar at NYU Wagner School of Public Service and a senior research scholar at the Rudin Center for Transportation Policy and Management at the Wagner School from January 2018 through August 2019. He has master’s degrees in business administration from the Stern School of Business at NYU and in public and international affairs from the School of Public and International Affairs at Princeton University.

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).