Special-Needs Students: A Look at What the Success Academy Charter School Network Does — and How

82 percent of Success Academy special-needs students are proficient in math, 60 percent in English

New Yorkers have come to expect the extraordinary from Success Academy charter schools. So when results from the 2017 state exams were released, it wasn’t surprising that 95 percent of Success students scored proficient in math and 84 percent in English (compared with city district school averages of 38 and 41 percent, respectively).

“Students with special needs seem to be well served at charters.”

What was notable, even for Success, was the performance of the network’s students with disabilities.

Of Success students with special needs, 82 percent scored proficient in math and 60 percent in English. Success reports that even among its students with moderate to severe learning disabilities — those assigned to self-contained classrooms with other students who have learning disabilities — 54 percent scored proficient in math and 32 percent in English. Astonishingly, Success students in self-contained classrooms outperformed both district and charter school math proficiency averages.

The city’s charter sector overall is serving more students with disabilities. While charters used to educate smaller percentages of students with disabilities than district schools, the gap has been virtually eliminated. Last year, 17 percent of city charter students received special education services, compared with 18 percent in district schools. (If pre-K isn’t included, the district special education percentage rises to about 20 percent but the charter percentage stays the same.)

More important, students with special needs seem to be well served at charters. Of charter students with disabilities, 27 percent scored proficient in math last year and 20 percent in English, compared with proficiency rates of 12 percent and 11 percent, respectively, for students with disabilities in district schools.

Advocates complain that the city doesn’t provide adequate support for students with special needs. All special education classifications, at both district and charter schools, must go through the city Education Department’s Committee on Special Education, which reviews evaluations and decides with school representatives and parents whether a child needs an Individualized Education Program. The IEP spells out the most appropriate educational supports and classroom setting.

A recent report indicates that last year, 27 percent of special education students in district schools weren’t receiving their mandated services or appropriate classroom placements. A federal lawsuit against the Department of Education has been filed on behalf of Bronx students with disabilities who weren’t receiving services to which they were entitled.

(In New York, both district and charter schools refer students with the most severe learning challenges to the specialized District 75 program, which serves about 24,000 students scattered among 60 schools, as well as those receiving instruction in hospitals, through agencies, and at home. District proficiency figures include a few students from the District 75 program, but not enough to change the percentages.)

While the city’s charters are serving more students with special needs, the growth and achievement of Success Academy’s special education population stands out. The number of students with disabilities at Success has nearly tripled, from 765 in 2013–14 to 2,048 in 2016–17. (These are year-end figures supplied by Success; due to data quirks, the state reports Success as having slightly higher numbers of students with disabilities.) About 16 percent of the network’s students have special needs.

Success also serves more students with moderate to severe learning disabilities who require self-contained 12:1:1 classes (12 students, one teacher, one aide) than it used to. In 2015–16, only five such classes existed in the network. This year, Success has 24 self-contained classes serving 288 students. Not all Success schools have room for self-contained classrooms, so when students need that level of support, the network seeks space in one of its 17 schools offering 12:1:1.

According to Success, about 10 percent of its students with disabilities are in self-contained classrooms. Another 60 percent are in Integrated Co-teaching classes, which have two teachers and a mix of special education and general education students. The remaining 30 percent are in general education classrooms and are pulled out for special ed services during the school day.

Success students without disabilities score among the top 2 percent of all students on state exams. So it shouldn’t be totally surprising that students with special needs also perform exceedingly well. As one special education expert explains, “Good schools are good schools for all kids.”

Danique Day-Loving, principal of Success Academy Harlem 1, where 17 percent of students receive special education services, echoes that sentiment. She credits the achievement of those students to the network’s content-rich curriculum and the fact that teachers monitor student work so closely that they see immediately if there’s a problem.

Federal law requires that students with disabilities have equal access to the general education curriculum to the greatest extent possible; Success, Day-Loving says, uses the same general education curriculum for students with disabilities but supplements it with programs such as Stern Math and Leveled Literacy.

Julie Freese, who oversees Success’s special education efforts, believes the network’s inquiry-based learning philosophy — which keeps teacher talk to a minimum and asks students to “own the learning” by grappling with math problems and writing exercises — is well suited to special education. Freese also notes that Success staffs its 12:1:1 and ICT classrooms with lead teachers experienced in special education. “We put our best teachers with our most vulnerable students,” she notes.

“While the city’s charters are serving more students with special needs, the growth and achievement of Success Academy’s special education population stands out. ”

Success famously emphasizes the state exams. Students, including those with disabilities, take practice exams, and their scores are posted inside the school. Brian Whitley, Success’s director of media relations, says students get testing accommodations if required in their IEP but “we believe state exams are important measurements of student achievement” and it can be “a powerful confidence booster for [students with disabilities] when they can and do make significant progress.”

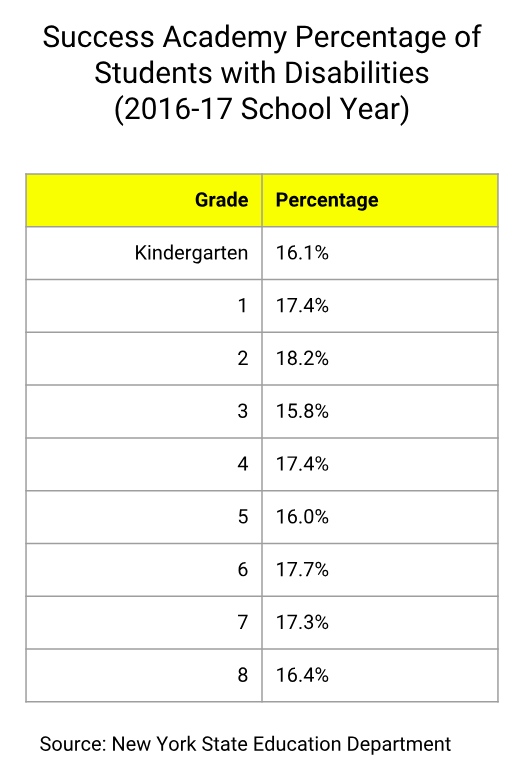

Skeptics insist that in order to generate these eye-popping test scores, Success must not be admitting students with severe disabilities or behavioral challenges, or must be pushing them out once they’re admitted. But there’s no empirical evidence that this is happening on a widespread scale. As the chart below indicates, the percentage of students with disabilities at Success fluctuates slightly, but there’s no systematic decline in special education rates as grades advance.

Previous studies by the city’s Independent Budget Office and my Manhattan Institute colleague Marcus Winters have found charter school students with special needs to have slightly lower attrition rates than their peers at district schools. These studies, however, don’t disaggregate rates among charter schools, which would be a welcome addition to the research. A recent IBO study found that 11 percent of the city’s students with disabilities transfer schools each year, but it didn’t break out rates for charter and district schools.

Is Success suspending students with disabilities at a rate that might encourage parents to withdraw them from the school? According to state data, in 2015–16 Success suspended 11 percent of its students, about three times the district rate but on par with some other charter networks. (Charters now report how many students have been suspended but not how many times each student may have been suspended. The state doesn’t break out suspension rates for students with disabilities. New York should change its policies to collect and report these data.)

Success wouldn’t provide specific data on suspension rates of students with disabilities, but Whitley says the network makes some accommodations to “avoid situations that would require disciplinary action and to help scholars build skills to successfully navigate challenging situations.” He notes, however, that Success does discipline students with disabilities if there is a safety issue.

Success has a fairly restrictive “backfill” policy — after the beginning of fourth grade, students who leave are not replaced. Success claims the policy is necessary to build its unique academic culture. Backfill plays a part in Success’s phenomenal test scores, in general education and special education, but not as large as some suggest. Student proficiency rates are just as high in third grade as they are in eighth. Regarding students with disabilities, third-grade proficiency rates of students with special needs at Success (91 percent math; 64 percent English) are generally higher than eighth-grade proficiency rates (57 percent math; 74 percent English).

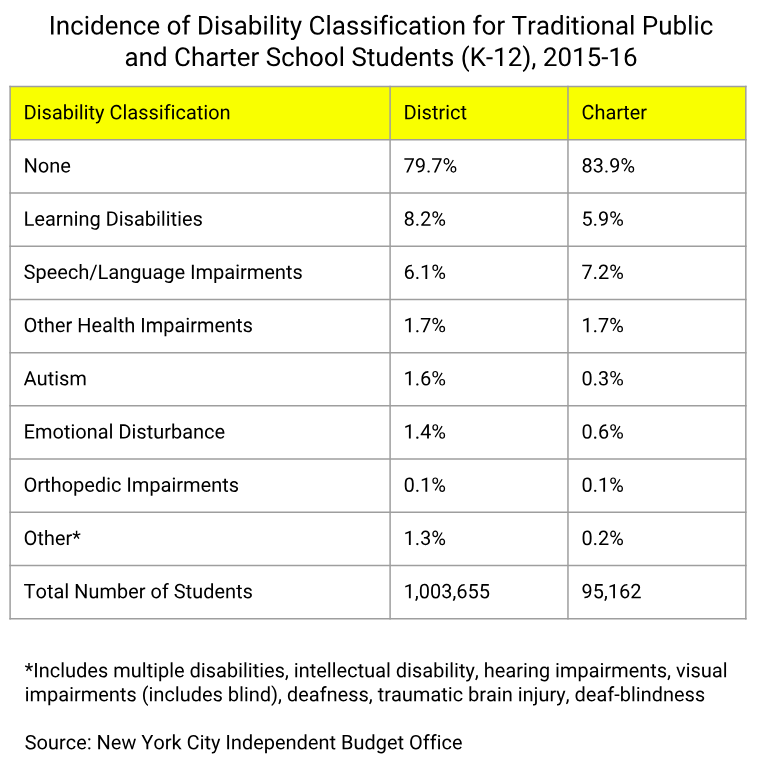

A crucial question is whether Success is primarily serving students with less severe disability classifications than district schools and other charters. According to IBO data, of the 13 formal disability classifications, the two that cover over 70 percent of students with disabilities in district and charter schools are “learning disabled” and “speech/language impaired.” Although they declined to provide hard data, Success officials say the majority of their special-needs students are represented in those same two classifications.

As the table below indicates, in the 2015–16 school year, charters served a slightly lower percentage of students in the “learning disabilities” category than traditional district schools and a slightly higher percentage in the “speech/language impairments” category. Data show district schools serving much higher percentages of students in the less common but more severe categories of autism and emotional disturbance (as well as the “other” category below, which includes multiple disabilities). District numbers, however, include the 24,000 students in the city’s specialized District 75 program.

Success Academy’s stated mission is to “redefine possible.” The network appears to be doing just that with special education; however, more student-level analysis is needed to say for sure. Are students with special needs applying, enrolling, and persisting at Success Academy at rates similar to those at other district and charter schools? Does Success classify or declassify students with disabilities at a higher rate than other district and charter schools? Does Success primarily serve students with less severe learning disabilities than other district and charter schools?

A well-designed research study could shed light on these important questions and provide a fuller, more nuanced understanding of the extraordinary exam results being attained by the growing number of students with disabilities at Success Academy. Here’s hoping that Success will agree to such a study. With results this astonishing, attention must be paid.

This piece originally appeared at The 74

______________________

Charles Sahm is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute. Follow him on Twitter here.

This piece originally appeared in The 74