Reforming “Raise the Age”

In 2018, New York State enacted its “Raise the Age” (RTA) legislation, which raised the age of criminal responsibility from 16 to 18 years old. Under RTA, 16- and 17-year-olds accused of misdemeanors go to family court, where they can be adjudicated as juvenile delinquents. A 16- or 17-year-old accused of committing felonies is considered an “adolescent offender” (AO). When an AO is arrested for a felony-level crime, his case is initially heard in the “youth part” of the criminal/supreme/superior court system (what we’ll call “adult court” going forward). But most of these cases are quickly “removed”—that is, transferred—to family court or even directly to family court probation.

Under RTA, in order for a prosecutor to keep an AO in adult court, he must prove by a preponderance of the evidence that:

- the defendant caused significant physical injury to a person other than a participant in the offense; or

- the defendant displayed a firearm, shotgun, rifle, or deadly weapon, as defined in the penal law in furtherance of such offense; or

- the defendant unlawfully engaged in sexual intercourse, oral sexual conduct, anal sexual conduct, or sexual contact.[1]

But these factors are harder to satisfy than they might seem. Consider, for example, a case in which a gang of teens beat someone up. In order to charge the defendants with basic assault, it would be enough to say that they “acted in concert” (i.e., worked together). But to meet the “physical injury” test to keep the case in adult court, prosecutors must be able to show which specific defendant caused a specific injury to a specific victim. If it is impossible to tell whose fist caused which injuries, the case goes to family court.

RTA also allows for an AO’s case to stay in adult court if “extraordinary circumstances exist that should prevent the transfer of the action to family court.”[2] The legislature, however, has not defined the term “extraordinary circumstances.” As such, when considering these requests, youth-part judges must look partly to the legislative history,[3] which directs them to consider “all the circumstances of the case, as well as the circumstances of the young person” but also suggests that the presumption in favor of removal will be overcome in “only one out of 1,000 cases.”[4] Moreover, state law sometimes prevents youth-part judges from considering all relevant information about the defendant when making this determination.

RTA has drastically reduced the number of 16- and 17-year-olds in the adult court system. Virtually all misdemeanor arrests of 16- and 17-year-olds go directly to the family court system. As of September 15, 2022, approximately 83% of felonies ended up there, too.[5] That includes roughly 75% of violent felony / Class A felony cases (except those involving drugs). Because family court proceedings are sealed, it is difficult to track what happens in these cases once they are removed.

Finally, when cases cross the bridge between adult court and family court, victims are left wondering whom to contact to find out the results of their case. The prosecutor who initially handled the case is generally barred from accessing the family court records that would reveal its ending. And while (at least in New York City) corporation counsel attorneys may have access to the results, they are limited in what they can say, even though the proceedings are open for the public to attend.

In order to fix the negative consequences of RTA, I recommend the following steps:

- Youth-part judges must be allowed to consider a defendant’s full history—including all family court records—when deciding whether to keep cases in the adult court system.

- The legislature should refine the standards used in removal hearings in order to remove ambiguities and to account for real-world scenarios that commonly occur:

- The “significant physical injury” standard should be abandoned. Rather, the legislature can achieve a similar effect by designating certain crimes that typically involve serious injury as warranting adult treatment as a matter of law.

- Rather than require prosecutors to prove that a defendant “displayed a firearm, shotgun, rifle, or deadly weapon” to commit a crime, they should have to prove that a defendant “displayed what appeared to be a firearm, shotgun, rifle, or deadly weapon” and let the defendant rebut that evidence.

- The “extraordinary circumstances” fallback test should not be so burdensome that prosecutors will meet it only “one in a thousand times,” as some legislators intended it to be. Rather than require “extraordinary circumstances,” courts should consider three factors: (1) Was the crime particularly heinous or unusual? (2) Are family court services likely to benefit the youth, or has he tried and failed them before? (3) Do aggravating factors outweigh mitigating circumstances?

- The courts or the executive branch must provide granular data on the results of RTA cases, from arrest to final disposition. These should be anonymized but must include probation outcomes. It is not enough to have different sets of data from different agencies.

- Victims must be given a central point of contact to find out what happened to the defendant in their case. Similarly, there needs to be a central point of accountability for the entire system. Adolescent cases jump between the DA’s office, the adult court, the family court, the City Law Department, and probation, with no individual agency taking ownership of the system.

Introduction: Before Raise the Age

Before Raise the Age, 16- and 17-year-olds who were arrested for crimes would be tried in the adult court system. Despite being tried in adult court, most 16- and 17-year-old defendants were not actually treated as adults. Many of these defendants, depending on their crime and criminal history, would receive a “youthful offender” (YO) adjudication instead of a conviction. YO adjudication allowed these youths to avoid a criminal record and full criminal responsibility—with records automatically sealed and sentences greatly reduced. For defendants charged with a misdemeanor, YO status had to be granted so long as they had no previous convictions. For those charged with a felony, the courts had discretion about whether to grant YO status. In 2013, 75% of 16- and 17-year-old defendants who were convicted of a crime in adult court received a YO adjudication and thus did not face full criminal responsibility.[6]

Despite this leniency, the state decided in 2018 that the age of criminal responsibility should be raised.

The Results of RTA

In New York City, adolescent crime trends in the wake of RTA’s enactment are concerning. Crime across the city has increased; so, too, has the adolescent recidivism rate. In the first year after RTA was enacted, 48% of 16-year-olds who were arrested once were arrested again. That’s up from 39% the previous year. For felonies, it rose from 26% to 35%; and for violent felonies, from 18% to 27%.[7]

Youth gun crime in the city has also increased by almost 200%. In 2017, 30 identified shooters were under 18. In 2022, as of August, there had already been 85. Youths are also the victims of gun crime about three times as often as they were five years ago, with 36 victims under 18 in August of 2017 and 111 to the same month in 2022 (Figure 1).

Figure 1

NYC Youth Shooting Victimization

NYPD’s Office of Crime Control Strategies found that “the relationship between youth gun arrests and subsequent shooting involvement (i.e., as an offender or victim) has grown substantially worse over the past few years.”[8] In 2017, 4.4 out of every 100 individuals arrested with a gun while under 18 years old were involved in a shooting within a year. By 2020, that number had nearly tripled, to 12.9%. In 2021, it was up to 13.7%. The two-year shooting involvement rate jumped from 6.7% in 2017 to 23.4% in 2020.

Among 18- to 24-year-olds, by contrast—who are “the most shooting-involved age cohort”—the one-year shooting-involvement rate rose from 3.7% in 2019 to only 5.1% in 2021. The report concluded that “young people under 18 now have a substantial risk of shooting involvement following a gun arrest relative to other groups and prior years.”[9]

Figure 2 shows the percentage of youth gun arrestees who are involved in a subsequent shooting over time and by year.

Figure 2

Shooting Involvement Following Youth Gun Arrest, 2014–2021

Outside Gotham, cities are faring little better. Some of the best data on the effects of RTA, however, come from Albany County, where District Attorney P. David Soares decided to keep track of cases that started in the youth part, as shown in Figure 3. Note that one defendant may have multiple cases in these charts.

Figure 3

Youth-Part Outcome, Albany County, October 2018–October 2022

Almost 85% of cases originally brought to the youth part were removed out of the adult court, either with a direction that the defendant appear: (1) for “adjustment consideration” before the family court intake office of the county Department of Probation; or (2), absent such direction, that the defendant appear before the family court for the origination of delinquency proceedings.Albany also tracked the recidivism rate among its most violent criminal youths. To figure this out, the DA looked at the 158 individuals who had been arrested as a violent adolescent offender (AO) between October 2018 and October 2022. A total of 57 were rearrested as an AO or an adult, including 35 for committing another violent crime (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Recidivism for Violent Felony Offenders, October 2018–October 2022

The History of RTA

How did New York get here? Former senior executive assistant Bronx district attorney Eric Warner provides an excellent historical overview in his Juvenile Offender Handbook, on which the following section relies heavily.[10]

Early Protections for Children and Teens

In the 1820s, New York State first recognized a difference between adults who commit crimes and children who commit crimes when it started housing younger offenders separately. A century later, it started charging young offenders separately, in “juvenile delinquent” (JD) cases. Warner notes: “Juvenile delinquency was defined to include all violations of the then-existing Penal Law committed by individuals under the age of 16 [later 15], except those violations punishable by death or life imprisonment.”

In the 1960s, the family court was given exclusive jurisdiction over all cases in which 7–15-year-olds committed “an act that would constitute a crime if committed by an adult.”[11] Along with the changes came a whole new vocabulary to describe youthful indiscretion. Juveniles were now referred to as “respondents,” rather than “defendants,” and the court’s stated “purpose” focused on the individual’s—as opposed to society’s—“needs and best interests.” Supervision and treatment outranked confinement as goals of the family court system. Only later, in 1976, was the court’s purpose expanded to include “the need for protection of the community.” Even still, as Warner notes, “juveniles could never be held criminally responsible for their actions; and juveniles were never stigmatized with a criminal record.”

The Pendulum Swings Back Toward Criminal Responsibility

In the 1970s, this simple age-determines-court system started to break down, with a series of reforms, culminating in the juvenile offender (JO) law of 1978. Under this law, 13-, 14-, or 15-year-olds charged with murder—and 14- or 15-year-olds charged with other serious felonies—would be prosecuted in adult criminal courts and face criminal responsibility (including potential life sentences when authorized) for their actions.

At this point, the majority of “crime committers” under 16 (JDs) went to family court, which, while tougher on “crime” than it had been in the early 1970s, primarily focused on personal rehabilitation. Some who committed more serious crimes (JOs) went to the local and superior criminal courts (which we’re calling “adult courts”).

A Supreme Court Case Changes the Landscape Nationally

In 1993, 17-year-old Christopher Simmons, along with an accomplice, broke in to Shirley Crook’s bedroom. She recognized Simmons from a previous unrelated car accident. Simmons duct-taped her, brought her to a local park, and threw her into the river below. He was convicted of murder and sentenced to death.

Twelve years later, in Roper v. Simmons, the Supreme Court overturned his sentence, finding the death penalty unconstitutional for anyone under 18. Justice Anthony Kennedy, writing for the 5–4 majority, cited scientific research that, he claimed, proved that there are “general differences between juveniles under 18 and adults,” which make JOs categorically less culpable for their crimes.[12] In dissent, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor argued that a young defendant’s culpability should be determined on a case-by-case basis: “[S]ome 17-year-old murderers are sufficiently mature to deserve the death penalty,” and juries are capable of “accurately assessing . . . maturity” and weighing “the mitigating characteristics associated with youth.”[13]

New York Rethinks Juvenile Justice

Even though Roper addressed the death penalty only for younger offenders, Kennedy’s reasoning started to seep into broader debates about juvenile justice. In 2008, New York governor David Paterson commissioned a task force charged with examining possible reforms to the juvenile-justice system. Although the task force was primarily charged with considering issues related to youth incarceration—such as alternative placements, reentry, and the conditions of confinement—many of its members thought that the age of criminal responsibility itself warranted scrutiny.

In 2012, Jonathan Lippman, chief judge of New York, proposed legislation establishing a new “youth division” in the state’s courts to adjudicate cases in which 16- and 17-year-olds were charged with nonviolent criminal conduct.[14] The chief judge claimed that the reform “would combine the best features of the Family Court and the criminal courts.” Like family court, it would offer alternative options, such as an “adjustment process,” that allowed for “probation supervision in lieu of a court proceeding.” For cases in which adjustment was not available, a “specially trained judge” in the youth division would apply adult court rules—which, Lippman notes, provide “greater procedural protections”—but not adult court penalties. Instead, family court procedures would apply after an adjudication of guilt: no criminal records, sealed files, “broader dispositional options,” and a “least restrictive alternative” principle. Lippman’s proposed legislation failed to pass into law, but by the next year, New York courts had established pilot programs that applied its principles.[15]

The Commission on Youth, Public Safety and Justice

In his 2014 State of the State address, Governor Andrew Cuomo declared the state’s juvenile-justice laws “outdated” and proclaimed that “it’s not right; it’s not fair. We must raise the age.”[16] Later that year, he established the Commission on Youth, Public Safety and Justice, instructing it to “develop a concrete plan to raise the age of juvenile jurisdiction.”[17]

The commission comprised a smorgasbord of criminal-justice stakeholders. They held nine meetings (one public), and then wrote a 164-page report, which offered seven reasons to “raise the age” now:

- Public safety would “actually be enhanced” by emphasizing public health services over the court system;

- “Both offenders and their communities are harmed by placing adolescents into adult jails and prisons”;

- New York was one of only two states with an age of criminal responsibility of 16;

- “The impacts of processing all 16- and 17-year-olds in the criminal justice system fall disproportionately on young men of color”;

- Recent scientific evidence showing that “portions of our brains, including the region governing impulse control, develop far later than expected,” as well as new science showing that adolescents “respond more fruitfully to efforts to rehabilitate them and put them on the right track”;

- Justice Kennedy’s Supreme Court decision in Simmons and other judicial opinions since have “encouraged reform efforts across the country”; and

- A “significant decrease in violent crimes committed by youthful offenders” has reduced the “outsized fears” of “super predators” infecting society.[18]

In support of its first argument for raising the age—enhanced public safety—the report even claims that its proposals would “eliminate between 1,500 and 2,400 crime victimizations every five years as a result of these recidivism reductions,” citing unpublished analysis performed for the commission by the Division of Criminal Justice Services.[19]

In April 2017, debate over Raise the Age finally made it to the floor of the New York State Assembly. Assemblyman Joe Lentol, who sponsored the bill, was the center of attention. Many of the questions that he faced from fellow legislators presaged problems that were faced by judges months later, when the law was enacted. Lentol’s responses ranged from the inciteful to the sarcastic, but the bill passed.

How RTA Works

RTA applies only to individuals who commit a crime before turning 18.[20] The easiest way to understand the legislation is to ask two questions about people under 18 who commit a crime: To which court do they go after they’re arrested? And how does the court treat them once they’re there? Let us consider the options, age group by age group.

RTA Courts and Classifications

Before RTA, the statutory age range for categorizing youth as “juvenile delinquents” was from seven to 16 years old. In 2018, the upper age for delinquency proceedings was raised to 18, but the lower age limit remained unchanged. In a change that becomes effective in December 2022, the lower limit was raised to 12, with one exception. Going forward, juveniles in this age range who would have been subject to delinquency proceedings will now be eligible for preventive social services and family support services instead. The exception is for those charged with homicide (other than criminally negligent homicide), who still face delinquency proceedings in family court.

Figure 5 shows an outline of who goes to which court after RTA. The 12-year-olds are never criminally responsible for conduct and always go to family court.

The 13-year-olds are usually treated the same as the 12-year-olds; for the vast majority of “crimes,” they are subject only to juvenile delinquency proceedings in family court. However, for some forms of murder, they are sent to adult court and treated as JOs.

The 14- and 15-year-olds are treated similarly to the 13-year-olds, but the range of crimes that can land them in adult court as JOs is much broader, including felony murder, robbery, weapons possession, and forcible rape.

The 16- and 17-year-olds used to be treated as adults, no matter what. What RTA did was “raise the age” at which an individual would always be treated as an adult. Now it is 18. So 16- and 17-year-olds can end up with one of two designations: (1) in family court as juvenile delinquents; or (2) in adult court as “adolescent offenders” (AOs).

Figure 5

A system that ended here—with certain designations landing certain individuals in certain courts—would at least be straightforward. Where RTA complicates things is in its removal provisions, which sometimes allow for a case to be transferred from adult court to family court after the case has already begun. Unfortunately, the rules governing removal are somewhat arbitrarily different for 14-year-olds and 17-year-olds, and that breeds unreliability.

Removal

To recap: “offenders” indicates adult court; so 13-, 14-, and 15-year-olds who start in the adult court system are “juvenile offenders.” The 16- and 17-year-olds who start in the adult court system are “adolescent offenders.”[21]

For a JO, the rules for removal from adult court to family court are relatively straightforward. Any party, including the court itself, can make a motion to remove the case to family court after indictment. (Motions can be made pre-indictment, too; but it’s a bit more complex, and similar standards apply.) In deciding the motion, the judge is instructed to consider nine factors:

- The seriousness and circumstances of the offense;

- The extent of harm caused by the offense;

- The evidence of guilt, whether admissible or inadmissible at trial;

- The history, character, and condition of the defendant;

- The purpose and effect of imposing upon the defendant a sentence authorized for the offense;

- The impact of a removal of the case to the family court on the safety or welfare of the community;

- The impact of a removal of the case to the family court upon the confidence of the public in the criminal-justice system;

- When the court deems it appropriate, the attitude of the complainant or victim with respect to the motion; and

- Any other relevant fact indicating that a judgment of conviction in the criminal court would serve no useful purpose.

It is worth highlighting the sixth factor: the impact of a removal of the case on the safety or welfare of the community. As will be discussed below, this is not a factor that judges are allowed to consider when asked to determine whether an adolescent case should be transferred to family court.[22]

For 16- and 17-year-olds, the system is more complicated. If they are charged with a misdemeanor (except vehicle and traffic offenses),[23] they are automatically sent to family court to face juvenile delinquency proceedings.

When an AO is arrested on a felony, though, he is sent to a newly designed “youth part,” which is in the adult court system but is staffed by a family court judge. If there is no youth part available, the adolescent will be arraigned by an “accessible magistrate,” trained in RTA procedures, who acts in place of the youth-part judge. Bail may be set, but if it is, the defendant will be seen by a youth-part judge as soon as he or she is available. That judge can modify bail, thus giving the defendant a second chance at release.

The Three-Factor Test

At this point, the important question is whether the case will be removed to family court. To keep the case in adult court under RTA, it is not enough to allege that the defendant committed a designated crime of violence—a type of crime with which prosecutors, defense attorneys, and judges have been familiar for years.[24] Instead, RTA requires prosecutors to produce specific evidence about the offense in question to determine whether it satisfies what is colloquially called the “three-factor” test. The test requires prosecutors to prove by “preponderance of the evidence”—essentially “more likely than not” or “51% likely”—that the defendant: (1) caused significant physical injury to another person (but not someone taking part in the crime); or (2) displayed a firearm, shotgun, rifle, or deadly weapon; or (3) unlawfully engaged in one of various sexual acts.

The law does not require a hearing to determine whether any of these factors has been met. It requires, instead, an “appearance.” This appearance has to happen within six days of arraignment, when facts are still in dispute. And there is no guidance for judges to follow to conduct an “appearance.” Prosecutors are put in an awkward position: Are they supposed to act as pseudo-witnesses and present evidence themselves, thereby discarding all the rules of hearsay and evidence that generally protect their record and the defendant’s rights? Or do they interrupt the lives of witnesses yet again—witnesses who will likely have come in for interviews with both the police and prosecutor and testify in a grand jury.

Lack of Definitions

The substance of what is required at this appearance is also unclear. Of the three factors in the test, the sexual-acts factor is least open to interpretation; the meaning of terms such as “intercourse” and “oral sex” are universally agreed upon. But factors one and two, which are far more commonly relied upon, are the source of much confusion.

Factor one requires a prosecutor to show that “the defendant caused significant physical injury to a person other than a participant in the offense.”

The phrase “physical injury” (sans “significant”) is defined in the penal law. It means “impairment of one’s physical condition or substantial pain.” Also defined in the penal law is the term “serious physical injury.” It means “impairment of a person’s physical condition which creates a substantial risk of death or which causes death or serious and protracted disfigurement, protracted impairment of health or protracted loss or impairment of the function of any bodily organ.”[25]

“Significant physical injury” is nowhere to be found in the penal law.

Why isn’t one of the laws linchpin decision points ever defined? The legislative history of RTA sheds light on this question. Assemblyman Lentol explained that, when the bill was being negotiated, the state senate and assembly could not agree on whether to use “physical injury” or “serious physical injury.” Instead, “in order to get a bill done,” they compromised, intentionally opting for a term—“significant physical injury”—that is not defined in the penal law. When pressed by his colleagues on what this term actually means—and whether it would cover, say, someone who passes out after being struck by a teen playing the “knockout game”[26]—Lentol was evasive, saying that he would not “speculate,” and was content to “let the courts decide what we mean.”[27]

In essence, the legislature could not agree on a term, so they made one up.

Again, this ambiguity could have been avoided if the legislature had opted to simply list the crimes that they found presumptively violent enough to insist that they be handled in the adult court system.

RTA’s causation requirement, which applies to each individual defendant, is also problematic. Normally, when individuals act together to cause a harm, each can be held legally responsible for the result. This usually makes sense. When a gang beats up a victim and fractures his eye socket, it may not be possible to tell which fist was making contact when the orbital bone cracked, but everyone who actively participated is culpable.

Prosecutors around the state have found the causation requirement—and thus the need to somehow label and trace every movement in a scrum—to be one of the most frustrating aspects of RTA. The requirement effectively punishes gang violence less severely than one-on-one fights. Gang assault, where the victim sees a switchblade plunge into his chest but can’t say for sure which attacker plunged it, is not likely to meet the requirement. If the legislature wants to make a quick commonsense change, it should start here. Allow judges to keep cases in the youth part when significant physical harm results from the defendant “acting in concert”—a term used elsewhere in the penal law, meaning “when one person engages in conduct which constitutes an offense, another person is criminally liable for such conduct when, acting with the mental culpability required for the commission thereof, he solicits, requests, commands, importunes, or intentionally aids such person to engage in such conduct.” Allowing something is not mandating something. Judges can tease out a gang assault from a kid barely contributing to a beat-down by his friends.

The second factor that can keep an AO in adult court—“displayed a firearm, shotgun, rifle, or deadly weapon”—has caused similar problems. In other areas of the law, displaying “what appears to be” a firearm in the commission of a crime is treated equivalently to displaying a firearm. Victims, after all, are not in the best position to diagnose whether the gun pointed at them was real.[28] But RTA dispensed with the “what appears to be” exception. Unless the gun—or perhaps a shell casing—is recovered, a defendant has a built-in argument that the alleged gun was, say, an imitation pistol. A stickup robbery on grainy video, where the robber throws the gun into the bushes, where it’s never found, will probably not meet the requirement. Whether a defendant ends up on the adult court track or the family court track becomes something of a game of chance, determined not by the severity of the crime or the strength of the evidence but by a narrow, arbitrary set of rules.

Lest one think that most youth-part cases are nonviolent, statistics from the Albany County District Attorney’s Office prove otherwise (Figure 6). Since RTA began, 58% of youth cases would be considered violent criminal cases if committed by adults. Of that grouping of violent cases, 30% (or 58) were violent because they involved guns.

Figure 6

Albany County: October 2018–October 2022

Extraordinary Circumstances—“One Out of 1,000 Cases”

Should the state not be able to prove one of the three factors, the only way the case can be kept in adult court is if the court finds that “extraordinary circumstances exist that should prevent the transfer of the action to family court.” What are “extraordinary circumstances”? That term, too, is undefined. Once again, the legislative history shows how difficult a standard this was intended to be.

Assemblyman Lentol, in response to a question about extraordinary circumstances, acknowledges that “extraordinary circumstances” is neither clearly defined in the bill, nor is it a concept used elsewhere in the law. Because it is “a new concept,” Lentol hesitates to give specific examples about what types of cases would meet the test. But he emphasizes how rare it should be: only when “highly unusual and heinous facts are proven and there is a strong proof that the young person is not amenable or would not benefit in any way from the heightened services in the family court.” Even if both these things are true, however, the judge should still consider transferring the case to family court if there are “mitigating circumstances.” In all, Lentol imagined that this standard would be so hard to meet that it would “apply in only one out of 1,000 cases.”[29]

Figure 7

The Judiciary

Judicial Blinders

The standard becomes even harder to meet in practice because youth-part judges cannot always consider all relevant information about the defendant. In Nassau County in 2019, a judge was asked to find extraordinary circumstances and keep in adult court a 16-year-old who had committed a string of robberies.[30] Prosecutors pointed out the defendant’s “extensive contacts” with the criminal-justice system dating back to 2014, including one juvenile delinquency adjudication for a felony-level offense and four for misdemeanor-level offenses. They further argued that previous intervention by the court, including sentencing the defendant to probation and releasing him to the custody of the Office of Children and Family Services, had done “nothing to curtail [his] behaviors.”

But the court would not consider this information. It cited section 381.2 of the Family Court Law, which states: “Neither the fact that a person was before the family court under this article for a hearing nor any confession, admission or statement made by him to the court or to any officer thereof in any stage of the proceeding is admissible as evidence against him or his interests in any other court.”[31] This view has started to become predominant among judges throughout the state.

In fact, youth-part judges may be barred from considering not only information from previous juvenile delinquency proceedings in family court but also information from previous proceedings in cases that began in the youth part of adult court and were then transferred to family court—even from cases in which they were the initial judge. Although the youth-part judge may consider the fact that the defendant was previously arrested, section 381.2 prevents him from considering anything that happened in the case after removal, including probation violations. This is particularly important because one thing that the judge must consider in determining whether there are extraordinary circumstances is whether the youth could benefit from family court services. But in making that decision, the judge has to pretend not to know that the defendant had already been offered those services and had continued to commit crimes.

Consider the implications of this rule. An adolescent defendant robs a man on Monday with what looks like a knife under his shirt. It’s the defendant’s first arrest. He’s sent to the youth part of adult court, and bail is not set. None of the three factors applies, and prosecutors concede that the circumstances are not extraordinary. His case is sent to family court and he receives probation, which includes having to attend counseling and wear an electronic monitor.

A month later, the defendant—who has not attended the required counseling—cuts off his ankle monitor, and he and an accomplice get into a shootout. The police find shell casings but no gun. The victim was running away. There is video, but it’s blurry. It’s unclear who fired the shots. The three-factor test can’t be met because no one can say which defendant “displayed” the weapon. The defendant is arrested again and appears before the same judge in the youth part. Prosecutors argue that the circumstances are extraordinary because the defendant has now violated his probation and committed a second felony in a month’s time. But because of section 381.2, the judge, despite having just seen the defendant, has to block off that knowledge. The case is again sent to family court.

A week later, the defendant is the subject of a search warrant. The police find a gun. They believe that it was the gun fired during the previous week. They want to test the shell casings from case number two, and they ask a judge to unseal the records. The judge declines. The defendant is arraigned. The judge considers the prior two arrests for the purpose of bail (which is allowed). But when asked to keep the case in adult court, the judge must again disclaim his knowledge of the defendant’s history.

The results are striking. As Figure 8 shows, in 2019, judges denied about as many extraordinary circumstances motions as they granted. Now, they deny about four times as many as they grant. This barrier did not have to exist. Had the legislature simply said that AOs start in the family court rather than in front of a family court judge, there would have been little question that the family court could rely on its own records.

Figure 8

A Better Extraordinary Circumstances Test

A better test—one that would respect the rights of RTA defendants but also retain the deterrent value of the adult criminal-justice system—might look as follows:

(1) Was the crime particularly heinous or unusual? (2) Are family court services likely to benefit the youth, or has he tried and failed them before? and (3) Do aggravating factors outweigh mitigating circumstances? Additionally, the law should require a determination that removal is in the interests of justice, and the Family Court Law should be amended to allow use of family court records in determining whether removal is in the interests of justice.

A defendant who failed one of these prongs would remain in adult court either because he refused to avail himself of the benefits of family court in the past, or he did something in the present deserving of more punishment than family court provides. The defendant would still have access to services in the adult court system but would also be subject to more severe consequences for failing to take advantage of those services.

This multipronged test would still allow those committing youthful indiscretions to avoid a criminal record. It would give an extra break to kids who act like bad kids occasionally. But it would take seriously kids who go beyond even the lenient line that society sets for them.

The RTA Divide

The Family Court Track

Figure 9 presents outcomes in youth-part cases for the last four years. In 2021, 36% of cases remained in adult court. Of these cases, 3% were converted to Superior Court Informations (SCI), which likely were used as vehicles for a plea deal; 9% were indicted and will move toward trial posture or a plea of their own; 11% are felony complaints, which means that they have yet to be presented to a grand jury and can still take multiple paths; and 9% are “continuing” in the youth part.

But most cases are removed. For three of the last four years, judges have sent over 70% of the cases heard in adult court to family court.[32] In 2021, 64% of youth-part cases were removed.

Figure 9

Youth-Part Case Outcomes

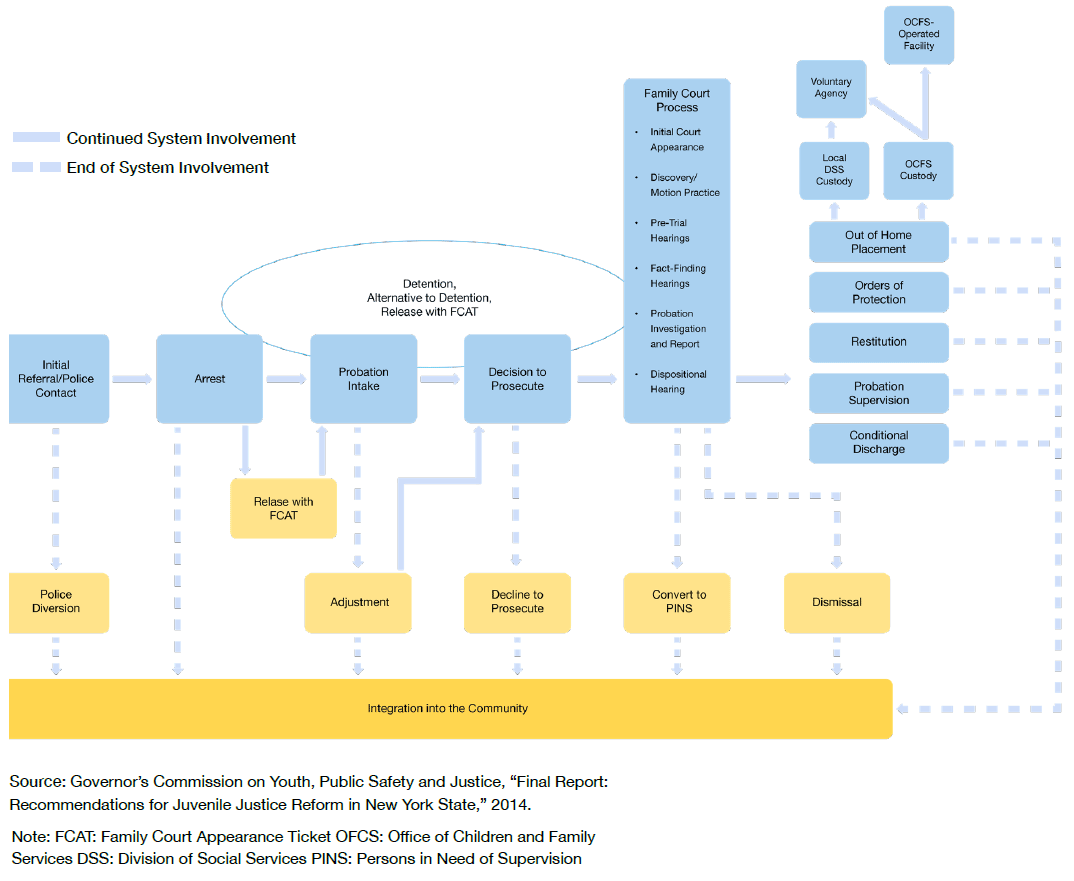

Once in family court, most defendants will never see a judge. They will receive diversionary adjustment by the probation department, and their case will be closed. This is because, in family court, the goal is integration and rehabilitation. The process starts with the probation department holding a preliminary conference with the arrested individual and, if possible, the victim. Probation officers determine whether the matter can be diverted from formal family court proceedings through what is called an “adjustment,” which may provide services and require participation in community service. Ultimately, the offender enters into a “Reparative Agreement, which details activities to be completed by offenders in order to repair the harm that was caused.”[33] This also offers a chance for the Department of Probation to screen and assess individuals for behavioral health disorders, which is valuable, even if the treatments available are sometimes suspect.

If not adjusted by the probation department, either the office of the county attorney (outside NYC) or the office of Corporation Counsel (inside NYC)—referred to as “the presentment agency,” instead of prosecutors—reviews the case and decides whether to decline to prosecute (thus ending the case), or to file a “petition,” which is analogous to an accusatory instrument containing charges against the juvenile.

If the presentment agency proceeds with the case, the juvenile is assigned counsel, and the case proceeds. The process culminates with an “adjudication of delinquency,” which is like a conviction, and a “dispositional hearing,” which is akin to sentencing. The court determines appropriate sanctions or treatment, including up to two years of probation or confinement, depending on an individual’s age and offense.

Figure 10

Juvenile Delinquency System

Family Court Track Outcomes

There are no granular data that allow us to trace each family court case from start to finish. But the Office of Court Administration does aggregate information about what happened in all cases that are assigned to probation upon entering the family court track each year. Figure 11 shows the distribution of outcomes in closed family court cases by year.

Figure 11

“Declined to Prosecute” means that the case was dismissed. “Petition filed” means that the juvenile essentially failed probation and was sent back to family court. “Success” is somewhat subjective: it means that a probation officer assessed that the juvenile completed the terms of a program into which he was placed.

When a case resolves itself in family court, judges now send juveniles to placement facilities only about 10% of the time (Figure 12).

Figure 12

Family Court Outcomes

The outcomes were similar when we look only at cases involving violent offenses, except that more juveniles were placed into probation (Figure 13).

Figure 13

Family Court Outcomes (Violent)

It is difficult to assess the success of treatment. Even judges have trouble figuring out what happened to a juvenile who was handed off to an institutional provider. Reports differ in quality, and probation officers sometimes do not follow up with program administrators.

Victims also suffer. After the case is in family court, the original prosecutor is no longer able to tell the victims what happened. If the case is exclusively handled by probation, they will have to rely on a probation officer for that information, and it may be limited to “he’s in a program.” If the case proceeds to family court, it is handled by the presentment agency, whose attorneys are limited in what information they can disclose to victims, despite the fact that any member of the public can attend proceedings in an open family courtroom and hear the outcome of a case.

Conclusion

RTA has both procedural and substantive flaws. What does “significant physical injury” mean? Why are older, generally more violent youths, treated more leniently than younger ones? Why are judges in the youth part of adult court—unlike family court judges in family court—precluded from considering information in family court records, even though that information might be critical to issues of public safety?

Equally concerning is the randomness of its outcomes. It is significantly easier for a prosecutor to keep a single assailant in the adult court system than it is to keep a member of a gang who engaged in a violent assault. This makes no sense.

Finally, there is a lack of transparency. The courts have done a good job in the last three years of collecting and displaying statistics. But this is not true for RTA cases. Before we can evaluate the impact of the law, we need meaningful access to granular data on case outcomes. It should be possible to learn, for example, what portion of arrests for criminal possession of a weapon in the first degree are removed to family court, as well as how many end in probation without a family court appearance. This will require the court system to coordinate with the NYPD and other state law-enforcement agencies.

In order to fix the negative consequences of RTA, I recommend the following steps:

- Youth-part judges must be allowed to consider a defendant’s full history.

- The three-part test to determine whether something remains in family court should ask: (1) Was the crime particularly heinous or unusual? (2) Are family court services likely to benefit the youth, or has he tried and failed them before? and (3) Do aggravating factors outweigh mitigating circumstances? Additionally, the law should require a determination that removal is in the interests of justice, and the Family Court Law should be amended to allow the use of family court records in determining whether removal is in the interests of justice.

- The state must amend the Family Court Act to account for real-world scenarios that commonly occur, such as: (1) gang assaults; and (2) display of what appears to be a firearm or deadly weapon.

- The courts or the executive branch must provide granular data detailing the results of cases from arrest to final disposition. This should be anonymized but must include probation outcomes.

- Victims must be given a central point of contact to find out what happened to the defendant in their case; similarly, there needs to be a central point of accountability for the entire system.

About the Author

W. Dyer Halpern is the former chief tax prosecutor at the Bronx County District Attorney’s Office. He prosecuted three wiretap cases over his 14 years in the office, returning millions of dollars in tax revenue to the City and State of New York. He taught courses on wiretap prosecution nationally to the National White Collar Crime Center and locally to the New York State Defenders Association. He currently runs his own law firm where he defends clients in federal and state court and serves as general counsel for a startup in the video game industry.

Endnotes

Photo: kali9/iStock

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).