Reform and Renewal: Opportunities in New York City’s FY 2024 Budget

Introduction

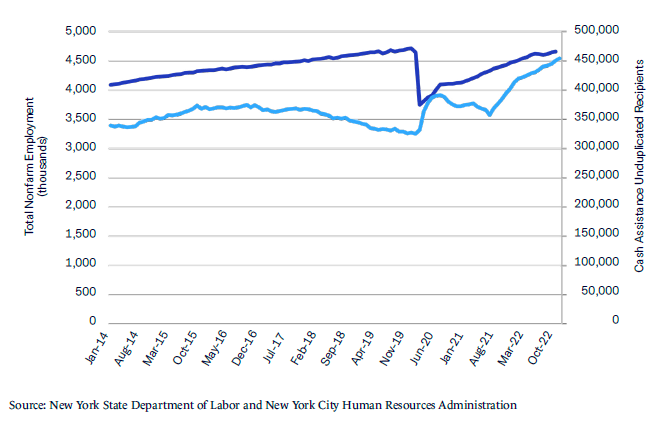

New York City faces an uncertain fiscal future. Vanishing federal pandemic relief, a struggling commercial real-estate sector, outmigration to other states, declining public school enrollment, persistent inflation, an above-average unemployment rate, the migrant crisis, enduring crime and disorder, and a lagging stock market are just some of the headwinds facing the city. Those only add to New York’s long-standing challenges in building housing supply, public-contracting inefficiencies, and controlling public pension costs.

Against this backdrop, Mayor Eric Adams and the New York City Council will soon finalize negotiations for the city’s FY 2024 budget, a document that will govern almost as many public dollars as Florida’s state government.[1] The decisions made this year will have crucial implications for the city’s ability to weather its uncertain environment. According to a March 2023 report from the city comptroller’s office, New York faces budget gaps of $7 billion in FY 2025 and $10 billion in FY 2026.[2] If the city does not close some of these gaps in the upcoming year, New Yorkers will be forced to contend with the prospect of higher taxes and service cuts in the not-too-distant future.

In this report, Manhattan Institute experts provide readers with a broad overview of the most important contributors to New York City’s budget. The departments and agencies that it explores constitute more than a majority of the city budget and affect the daily lives of New Yorkers. Each department contends with a unique set of political and bureaucratic issues, and all can be improved in several ways.

Each section of this report will first describe the department and its context within city government. It will then discuss the budget issues facing the department and suggest avenues for improvement. Readers will therefore learn not only about problems and limitations but also constructive steps that political leaders can take to address them.

Legal Frameworks for New York City’s Budget

John Ketcham

Director, State & Local Policy; Fellow, Manhattan Institute

The Context

Before midnight on June 30, per the New York City Charter, New York’s mayor and city council must negotiate and pass a balanced city budget according to generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP).[3] Each year’s adopted budget results from months of public input, city council hearings, and requests by councilmembers and the five borough presidents to allocate more funds for districts, boroughs, and programs. The many constituencies that have a stake in the city budget generally place pressure for higher government spending. The far fewer voices in favor of fiscal discipline include the city and state comptrollers’ offices, the charter-mandated Independent Budget Office, nonprofit groups like the Citizens Budget Commission, Empire Center for Public Policy, and Manhattan Institute, and, sometimes, the mayor.

But in addition to the balanced budget mandate, the mayor and the council do not have a free hand to set spending as they see fit. The New York State Constitution, state statutes, judicial decisions, and the city charter require the city government to conduct its affairs in ways that have an impact on its budget. From long-standing hiring and procurement requirements, to control over public-employee pension changes, to new conditions in each year’s state budget, Albany determines a sizable portion of the city budget.

Most directly, the state contributes about $17 billion, or 16%, of the city’s $106.3 billion revised FY 2023 budget.[4] Federal funds account for $12.4 billion, or 11.7%, an amount projected to drop sharply to $7 billion by FY 2026. But less directly, legal restrictions increase the city’s costs, and they impose trade-offs that limit city leaders’ ability to reduce taxes and expand services. They also limit the city’s ability to reform some of its largest expense items, such as education, pension benefits, and health care.

Some of these requirements pertain most directly to the capital budget, which is distinct from the operating (or expense) budget but determines the amount of debt that the city takes on, usually in the form of long-term bonds, which, in turn, affects the amount that the city pays annually in debt service. State laws that determine how the city conducts capital projects therefore bear an important relationship to its expense budget. Currently, debt service represents 7.7% of the FY 2023 city budget and is slated to climb to 8.9% of the FY 2026 budget. According to the state comptroller’s review of New York City’s FY 2023 budget, spending growth in 2022 and 2023 “is driven mainly by debt service and fringe benefit costs (other than pension contributions), such as health insurance.”[5]

Since the Covid-19 pandemic, the city has relied on one-time federal and state funding to pay for recurring operational costs. The Citizens Budget Commission found that, in 2021, at least $1.3 billion in federal aid went toward recurring programs, and $2.7 billion went toward potentially recurring programs such as housing vouchers and mental health services.6[6] Education spending was particularly prone to this practice; out of a total of $7.3 billion in federal pandemic relief funds for education between 2021 and 2025, the Independent Budget Office found that $3.2 billion would be spent on longer-term programs—such as three-year-old pre-K and special education—that require additional funding post-2025.[7] Yet when Mayor Adams and Schools Chancellor Banks attempted to reduce education spending in the FY 2023 budget, spreading out these limited federal funds over three years and gradually softening the impact on schools, a group of teachers’ unions and parent groups sued him, embroiling the city in a months-long legal battle in which the mayor emerged only partially victorious.[8]

The Issues: How City and State Laws Affect New York City’s Budget

State and local laws affect New York City’s budget in direct and indirect ways. These range from long-standing provisions of New York’s constitution, state law, and the city charter, to yearly changes in state funding enacted in the most recent state budget. Specific examples that substantially affect the city budget include the state’s funding to the city and laws governing public education, procurement, and public-sector employment.

State and City Funding Shares

Each year, just as the city council debates and ultimately compromises over the city budget, the New York State Legislature negotiates with the governor to pass the state budget, due by April 1, the start of the state fiscal year (though this deadline can be extended). This budget encompasses far more than fiscal matters and often contains provisions ranging from criminal justice to charter schools. City finances are already burdened by previous state budgets in a number of ways:

- New York requires counties to pay for a portion of Medicaid costs, up to a cap of $7.6 billion. For New York City, this mandate represents a $5.4 billion expense, or about 5% of the total budget.[9] Unsurprisingly, counties consistently object to this cost-sharing arrangement, in which they pay more than all other local jurisdictions in the nation combined.[10], [11]

- The FY 2015 state budget added a 10% cost share on New York City (and only the city) for the Emergency Assistance for Families program, and the FY 2019 budget introduced the same share for the Family Assistance program. These programs are part of the federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) block grant. Both programs’ city share increased to 15% in the FY 2020 budget.[12] This was estimated to cost the city approximately $34 million in FY 2020 and $68 million in FY 2021.

- The FY 2011 state budget required local jurisdictions to contribute 71% of the state’s Safety Net Assistance (SNA) program, which supports city shelters and provides temporary cash payments to needy individuals and families who no longer qualify for TANF because they have already reached its five-year time limit. Previously, local funds were split with the state 50-50. Governor Hochul’s proposed FY 2024 budget allots $767 million to cover the state’s 29% share; under a 50-50 split, the state would pay $1.32 billion.[13] State legislation also eliminated the 45-day waiting period for SNA benefits, effective as of October 1, 2022, further increasing city costs.[14]

- State funding to New York City schools varies from year to year. The FY 2020 state budget, for example, froze Foundation Aid, the main source of state funding to local schools that generally accounts for about 40% of school budgets.[15] The freeze meant that the city had to make up a $360 million shortfall from its January projection.

- The state’s share of probation funding has progressively crept lower, requiring the city to absorb an ever-greater share of costs. The city Department of Probation’s $124.97 million adopted FY 2022 budget, for example, comprised about $101.2 million of city funding (excluding intra-city transfers) and $14.8 million in state funding, or about a 6.8:1 ratio.[16] Compare that with FY 2009, when the department’s budget was $83.2 million, $60.4 million of which came from the city and $18.8 million from the state, or a 3.2:1 split.[17]

A number of taxes that exclusively or disproportionately affect city taxpayers also indirectly burden the city by limiting its ability to raise taxes further for local purposes. Since 1989, for example, the state’s mansion tax has imposed a flat 1.0% tax on buyers of homes over $1 million.[18] While inflation has eroded the value of that figure substantially since then, the tax threshold has not changed. As much of the state’s stock of high-value property is in New York City, its buyers have disproportionately borne the share of the mansion tax, especially as property values have risen dramatically over the past three decades. As part of the FY 2020 budget, the legislature increased the tax on homes $2 million and over in NYC, up to a maximum of 3.9% for homes $25 million and over, further increasing the tax burden on city taxpayers.[19]

Governor Hochul’s proposed FY 2024 budget, released on January 31, 2023, likewise proposes several other measures that would have billion-dollar impacts on future city budgets.[20] Though these are subject to change in the impending final budget, the governor’s proposals include:

- A $500 million direct city contribution to the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA), as well as increased payments for paratransit and student fares and an increased payroll mobility tax. According to an Adams administration memorandum, the governor’s transportation-related proposals are expected to cost the city approximately $530 million.[21]

- State-based assistance to address the influx of migrants from across the southern border to New York City, capped at $1 billion over the period of April 2022 to August 2024. This cost represents about 29% of the city’s estimated expenses related to the migrant crisis.

- Removal of the cap limiting the number of charter schools that can operate in the city, allowing for dozens of charter-school openings. The city must provide funding and space for these schools, which would represent an approximately $1 billion impact on the city budget when fully implemented. The additional re-issuance of 21 charters to schools that have since closed would add another $200–$300 million in city costs annually. The proposed budget, however, would increase Foundation Aid funding by $2.7 billion, of which the city would receive approximately $320 million.[22]

- Ending the state’s pass-through of Enhanced Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (E-FMAP) funding to local jurisdictions, which defrays local Medicaid costs. The mayor’s office estimates that this will conservatively cost the city $343 million annually in FY 2024 and beyond but warns that this amount is subject to increase.

- In all, a March report by the Citizens Budget Commission found that Hochul’s proposed budget would increase the state’s structural deficits by $15 billion by FY 2027.[23] These large deficits pose particular risks for New York City, as they increase the chances that Albany will maintain or even raise personal income taxes and business taxes, which, when combined, already amount to the nation’s highest.[24] They also limit the amount of funding that Albany will be able to give to help bridge some of the city’s own budget gaps.

State law also affects how the city can treat budget surpluses and savings. In 2019, voters approved a charter amendment allowing for the creation of a “rainy day fund” to stabilize city finances during market downturns; the state legislature followed up the next year with legislation allowing budget surpluses to be deposited into a new “Revenue Stabilization Fund” (RSF).[25] Before then, the city saved money by rolling current-year surpluses into prepaid expenses for the following year. Though state legislation limits RSF withdrawals to 50% in any given year—barring the mayor’s declaration of a “compelling fiscal need”—there is no legal structure in place to make consistent deposits to the RSF or set a target savings amount.[26] Last year, the city comptroller’s office proposed an automatic deposit rule of 50% of the difference between current and six-year average growth of the city’s non-property-tax revenues. If implemented, this would have increased reserves by $2.5 billion; instead, the mayor and city council added $750 million to the RSF in the FY 2023 budget. The chancellor also proposed a savings target of 16% of total taxes deposited into the RSF, enough to stabilize tax revenue for the length of an average recession.[27]

State Education Requirements

State law imposes direct and indirect restrictions on the city’s ability to control education spending. One important and recent example of a direct measure is legislation enacted last year that lowers the maximum number of students allowed in each New York City public school classroom.[28] Currently, state law caps class sizes at 25 for kindergarten, 32 for grades one through six, 33 for most middle schools, and 34 for high school.[29] Beginning in September 2023, the caps will, over a five-year phase-in, be lowered for kindergarten through grade three, to 20; for grades four through eight, to 23; and for high school, to 25. The city estimates that this will cost $500 million to implement in grades kindergarten through five and $1 billion across all grades. This mandate comes in the wake of a dramatic drop in school enrollment over the past several years of some 100,000 students; 1,002,200 students were enrolled in the 2019 school year,[30] compared with 903,000 this year.[31]

Indirect measures include those related to the mayor’s control over New York City public schools. In 2002, the state legislature abolished the city’s 32 local school boards and centralized decision-making in the city Department of Education (DOE), under the direction of the mayor and schools chancellor.[32] Because state law requires that each school district be governed by an elected or appointed school board,[33] however, NYC retained its citywide school board. Reconfigured as the 15-member Panel for Educational Policy (PEP), it is responsible for providing a public forum on educational matters and for reviewing and ratifying decisions made by the schools chancellor and the mayor in monthly public meetings. In 2022, the state legislature expanded PEP to 23 members, most of whom the mayor and borough presidents appoint, and curtailed the mayor’s ability to remove his appointees for voting against his wishes.[34]

Though state law expressly disavows any executive or administrative power for PEP,[35] it must conduct a 45-day public-input process, hold a public meeting, and approve an estimate of the upcoming fiscal year’s education budget.[36] Historically, DOE provided PEP with a high-level estimate that did not contain figures for individual schools, and the chancellor issued an emergency declaration that had the effect of granting provisional PEP approval so that the city budget could be approved before its hard July 1 deadline.[37]

Last year, following a lawsuit by a group of teachers’ unions and parent groups against cuts to school budgets in the FY 2023 city budget, a state appellate court held that PEP must approve the estimate before the mayor and city council pass the citywide budget. Going forward, PEP budget estimate votes will have teeth, especially now that the mayor will be unable to remove appointees at will. The mayor’s preliminary FY 2024 budget calls for a $337 million reduction in DOE spending, compared with FY 2023.[38] On March 22, months ahead of the July 1 city budget deadline, the newly empowered PEP voted to approve the mayor’s estimated funding.[39]

As this lawsuit demonstrated, stakeholders, especially city councilmembers and municipal unions, have come to expect—and will fight to retain—the level of service provision and spending made possible through these one-time revenues. Yet there is no guarantee that Washington or Albany will continue to provide them, especially between administrations, or that such spending is warranted or sustainable for the city in the long term.

Labor Agreements and Costs

New York City and State have long been among the most union-friendly jurisdictions in the United States. In 1958, Mayor Robert Wagner, Jr. issued Executive Order 49, granting city employees the right to collective bargaining and authorizing unions to speak for city workers—even for workers who are not members.[40] This was extended statewide through the 1967 Public Employees’ Fair Employment Act, often known as the Taylor Law, which outlawed public-sector worker strikes in exchange for the right to collectively bargain.[41] The Taylor Law contains a provision allowing some local laws to displace its terms, provided that the local laws are “substantially equivalent” to the state law’s “provisions and procedures.”[42] Also in 1967, NYC passed a law to that effect, known as the Collective Bargaining Law, to exercise this local option.

In 1982, in what became known as the Triborough Amendment, the state legislature amended the Taylor Law to require that the terms of a collective bargaining agreement (CBA) continue past expiration—including incremental pay raises—regardless of the government’s fiscal condition.[43] Unions therefore have little incentive to change outdated contract provisions, especially if the city’s fiscal health would warrant terms that are the same as or less generous than the terms under the expired agreement.[44] This is especially costly for teachers’ salaries, as teachers earn annual raises through “salary steps” that remain even under an expired contract.[45]

To cover the diverse assemblage of the 281,000 workers on its payroll, the city negotiates with approximately 150 distinct collective bargaining units, ranging from police officers to welders to microbiologists. These agreements cover wages, salaries, work rules, fringe benefits, and conditions of employment but not pensions or health insurance. While salaries and wages directly affect the city’s bottom line, work rules often limit employee productivity and make it difficult—if not impossible—for managers to reward or discipline employees based on achieving results.[46] This, in turn, requires the city to hire more employees, thus having a negative impact on the city’s labor costs.

Agreements covering police officers and firefighters further require that impasses be resolved by a three-member panel of unelected arbitrators who have the power to impose binding decisions on the city. This “interest arbitration” has the effect of raising uniformed labor costs by encouraging elected officials to settle on terms that might be disadvantageous for taxpayers, out of fear of an even worse arbitration decision.[47] Government officials have a strong incentive to avoid political pressure by disagreeing with the union and allowing the arbitrator to decide.[48]

Government-employee pensions are governed by state law, not by CBAs. Absent lobbying lawmakers in Albany, there is little that city officials can do on their own to affect the size of the city’s pension liabilities. The city can, however, take indirect steps to rein in pension costs, such as by not awarding discretionary raises and overtime pay, or by waiting to hire new workers until a new pension regime takes effect. And because of the great political pressures not to reduce pension benefits for newly hired workers, pension-related legislative changes are among the most difficult to achieve.

Some state laws provide specific benefits to certain classes of municipal employees. In 1988, the state legislature enacted a law adding an option to New York City teachers’ deferred compensation retirement plan that guaranteed an 8.25% rate of return, regardless of market conditions, which was lowered to 7.0% in 2009.[49] When enacted, the interest rate was generally in line with bond returns; but for most of the following 35 years, it was marked by declining or even zero interest rates, and the city’s general fund had to make up the difference.[50] In 2014 and 2015, this benefit cost city taxpayers $1.1 and $1.2 billion, respectively.[51] Fewer than 6% of retirees actually drew from the account, opting instead to allow the funds to grow, strong evidence that the perk proved too rich.

New York City’s employee and retiree health benefits are uniquely generous among any employer, public or private. Like pensions, these are not controlled by CBAs negotiated with each bargaining unit but are determined by the Municipal Labor Committee, a body recognized in city law[52] that represents a group of more than 100 municipal-worker unions comprising about 400,000 active and retired workers.[53] But in contrast to pensions, in which current employees pay into a substantial pool of assets that generate investment income to partially defray payments to current retirees, the city simply pays the annual health-care premiums for employees and retirees out of general revenues as they come due each year, a funding mechanism known as pay-as-you-go, or PAYGO.[54] The city’s adopted FY 2023 budget allocates $8.1 billion for these PAYGO costs.[55]

Further, New York City does not require municipal employees to pay for any portion of their health-insurance premium. For those who work for at least 10 years, or teachers who work for 15 years, the city provides lifetime comprehensive medical and hospital insurance, even for those workers who retired before being eligible for Medicare.[56] Upon reaching Medicare eligibility, the city reimburses retirees and their spouses for their entire Part B premiums.[57] Union leaders admit that this arrangement has come at the cost of lower wages, but unions have always responded to attempts to introduce health-premium cost-sharing with outright rejection.[58] Lawsuits delayed the city’s attempt, backed by labor leaders, to move about 250,000 municipal retirees and their dependents onto a Medicare Advantage program, but the city ultimately secured a vote from the Municipal Labor Committee that will allow the change to take effect in September 2023.[59]

These generous benefits represent a large and growing strain on city budgets. The city comptroller puts the cost of health insurance and fringe benefits for FY 2023 at $8.1 and $4.5 billion, respectively,[60] but these are expected to grow to $10.5 and $4.9 billion by FY 2026.[61] A 2017 Citizens Budget Commission report calculated that the future post-employment benefits accrued by current employees in FY 2017 totaled approximately $4.9 billion, or $13,111 per employee.[62] But the city paid out only about $2.5 billion that year for current retirees’ other post-employment benefits; ballooning pay-as-you-go costs thus represent a looming threat to the city’s future fiscal health.[63]

Public pensions in New York are guaranteed by several provisions of law. The state constitution expressly provides that public pension plans establish a contractual relationship between the state and participating employees, the benefits of which cannot be diminished or impaired.[64] Treating pensions in this contractual way also allows the Contracts Clause of the U.S. Constitution to prohibit the state from impairing pension obligations.[65] And New York courts have interpreted pension plans as a property interest, further insulating them from diminishment by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

In short, New York City must ensure that it meets its pension obligations, which represent a major component of the city’s expense budget. Contributions to the city’s five pension funds, covering civil employees, police, firefighters, teachers, and school administrators, amounted to $9.4 billion in FY 2023. These contributions depend partly on the amount that the market returns in a given year, so market downturns can require the city to adjust its budget higher in the latter months of its fiscal year to account for higher pension contributions. This occurred in November 2022, when Mayor Adams announced his first mid-November financial update to the FY 2023 adopted budget, in which he added more to projected city pension contributions: $861 million in FY 2024 budget, $1.97 billion in FY 2025, and $3.02 billion in FY 2026.[66]

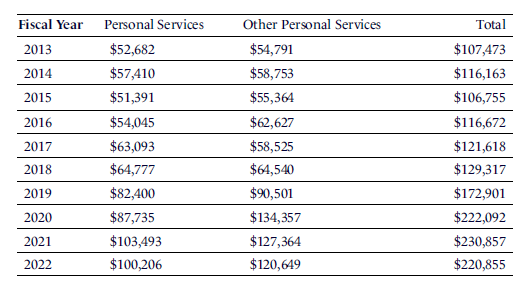

Zooming out, it’s not surprising, therefore, that personnel costs make up more than half the city’s budget. According to the city comptroller’s December 2022 financial report, salaries, pensions, and fringe benefits accounted for $53.4 billion out of a total of $104 billion in expenses, or approximately 51.3%. These figures are likely to climb higher, as the city reaches contract deals with remaining bargaining units.

Procurement and Capital Projects

Despite its massive workforce, the city cannot produce all the goods and services that it provides; it must, of course, procure goods and services from third parties, ranging from ink pens to homeless shelter services. In FY 2021, the city conducted more than 95,000 transactions, worth about $30.4 billion.[67] The procurement process thus has a major impact on the city budget and the effective provision of services, many of which take place through a vast network of third-party nonprofit providers. But procurement contracts vary widely in their budgetary impact. Procurements for under $1 million account for 90% of the total number of transactions but less than 5% of the total dollar value, whereas those for $3 million or more represent over 90% of dollar value.[68]

These large procurements are particularly important for the city’s one-year capital budget. This covers physical infrastructure (used for government operations or public use) whose debt service affects the city’s expense budget. Furthermore, the 138-year-old state Scaffold Law imposes absolute liability on property owners and contractors for any gravity-related job-site falls, regardless of employee fault—the only such liability regime in the United States. This burdens the costs of large publicly funded construction projects. Not only does the law contribute to nation-leading construction insurance premiums,[69] but the inability to defend a lawsuit on comparative negligence grounds has driven most insurers from the marketplace, hampering a competitive insurance market that can deliver lower prices. One estimate blamed the Scaffold Law for a 7% increase in affordable housing and other development costs.[70] The MTA’s newly completed East Side Access tunnel project, for example, originally budgeted $93 million for insurance in 2001; by 2018, the cost had risen to $584 million.[71]

New York State law further requires that all government contractors pay construction workers on public worksites at the so-called prevailing wage, which the state defines as that earned by at least 30% of workers in a particular trade—in other words, a union wage. For example, the prevailing city wage is currently $63.03 per hour for a tile layer[72] and $55.10 per hour for a drywall taper,[73] with at least time-and-a-half pay for any time after a seven-hour day, weekends, and holidays. These wages are considerably higher than the private-market wage for the same skills. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the median pay of a tile layer in 2022 is $22.74 per hour,[74] and $23.24 per hour for a drywall installer.[75] Even after considering New York City’s high cost of living, these differences are stark.

Traditionally, city agencies were required by state law to deliver capital projects using a “design-bid-build” process, in which the city first fully scoped and designed a project, and then selected contractors who had no part in the design to see the project to completion. State law requires that the agency select the lowest “responsible and responsive” bidder on competitive capital projects.[76] While this may sound like a money-saving directive, it has often wound up costing the public more over the course of a project, as some contractors with shoddy or nonexistent track records win a bid and yet underperform or dispute the contract, holding up the project or necessitating costly change orders. Other contractors may then sue the city successfully for damages caused by the delay; lawsuits between designers and construction companies are not uncommon.[77] The involvement of several city agencies can further lead to one agency’s priorities superseding project progress.

Other than the requirement that the bidder be “responsible,” the city cannot reject the lowest bidder and award the contract to another that it believes would provide better performance; price is the determinative factor.[78] Nor can the city enter into post-bid negotiations with losing bidders.[79] Its only option to reject a bidder is to reject all bids and solicit another round of bids for a rational purpose, such as additional project specifications.[80] These requirements ultimately reduce the quantity of public goods available; with the cost of a new public restroom in city parks now between $5 and $10 million,[81] it’s little wonder why more parks don’t contain facilities.

The risks associated with the lowest bidder directive are further compounded by the century-old state Wicks Law, which requires that city agencies obtain separate bids for general contracting, electrical, plumbing, and HVAC contracts in public projects exceeding $3 million.[82] New York is the only state to impose this requirement. Unless exempted, city agencies thus cannot utilize a “design-build” project delivery mechanism, which secures a single general contractor who then hires and coordinates subcontractors until the project is completed. Instead, the procuring agency must award up to four separate contracts and subsequently coordinate the project and all its various parties, even if they are unlikely to have had previous dealings. And because each of the four separate contractors must depend on one another to complete their respective portions of the project in sequence, a failure by any one of the four, or of the city agency to coordinate them in an effective manner, often leads to delays and costs well above the original contract amount. For these reasons, in late 2019, Governor Cuomo signed legislation that exempted seven city agencies from the design-bid-build process, in addition to the six agencies to which the requirement did not previously apply.[83]

That said, there are reasonable arguments in favor of retaining the current design-bid-build arrangement. The most important is the potential for higher design quality and greater control over the construction process for projects where design is a critical element. But allowing the city greater leeway to select contractors on the basis of value—which includes both performance and cost—would enable better project management and prevent delays and cost overruns.

Even if design-bid-build is retained for some city agencies, there is far less reason to support several separate agencies holding up projects to suit their own departmental needs and processes. Because several agencies are typically involved in large capital construction projects, each with its own mandates, incentives, and even payment processes, it can often be difficult for each to place the good of the project ahead of specific departmental needs. When one of these departments declines to proceed with one aspect of a project, work grinds to a halt.

Two pre-project compliance requirements further delay projects by months or even years. First, the city’s Office of Management and Budget (OMB) must review a project’s eligibility for capital funding and provide a “certificate to proceed.”[84] Second, the city comptroller’s office must subsequently “register” these certificates to proceed, in which it assigns the contract as a commitment for a given fiscal year, whether or not all actual spending will occur in that fiscal year.[85] Each budget modification triggers a fresh round of reviews and approvals. Both of these agencies usually have 30 days to conduct these reviews and provide approvals, but if either submits a question to the sponsoring agency, the 30-day clock resets, leading to months-long delays and thousands of hours spent gathering the information necessary to respond to these (often highly technical) questions.[86]

As the NYU Marron Institute’s recent Transit Costs Project Report notes, to build the Second Avenue Subway, the MTA (a state agency, but helpful for illustrative purposes) had to secure separate agreements from five different city agencies, utility companies, and others before proceeding with construction; these arrangements cost $250–$300 million, exclusive of the costs associated with delays that contractors incurred and claimed against the city.[87] Describing the dynamic that characterizes many public projects, the authors write that “satisfying every third party who has the ability to withhold a permit or slow down construction came at a cost.”[88]

Recommendations

There are important measures that city leaders could take to address fiscal problems within existing legal strictures, provided that sufficient political will exists. For example, despite the political headwinds that would accompany this move, the mayor could adopt a policy that time-limited federal and state funding will not be used for longer-term, recurring programs. This would achieve three goals. First, it would signal to stakeholders that the programs funded by time-limited relief will not persist after the funding period, thus setting expectations. Second, and consequently, it would likely reduce out-year budget gaps and the chances of potential fiscal cliffs. Third, it would require the mayor and councilmembers to make trade-offs about the recurring programs that should receive continued support and that should be cut back to ensure a balanced budget. Doing so would reduce the pressure to find $1 billion in FY 2026 to fund programs currently funded by federal pandemic dollars, according to a February 2022 state comptroller report.

Reforming the city’s project management and procurement practices can significantly lower costs and shorten project durations. In January 2023, the mayor announced a suite of proposed reforms to the public construction process.[89] These include state-level legislative proposals, such as allowing public agencies to use design-build processes, as well as local-level reforms such as streamlining change orders so as not to delay the entire project for extended periods of time. Specifically, Adams would like to expand a 2019 pilot called Expanded Work Allowance, which gives contractors access to a dedicated pool of money to continue work, despite change orders for parts of a project.[90] And Adams would do well to shorten the period necessary to obtain OMB capital eligibility approval and city comptroller registration before a project begins. One way to do this is to keep the initial 30-day project approval window in place (while allowing the initial steps in both to proceed in parallel), but require that approval or denial of good-faith budget modifications and question responses be resolved in five to seven days. According to a 2021 study by the Center for an Urban Future, reforming the capital construction process could save at least $800 million over five years.[91]

The mayor might also consider assigning a dedicated multiagency team to large capital projects, which would be tasked with seeing through projects from start to completion and would be given team-wide incentives to streamline approvals and achieve results. Backed by the mayor’s political clout, this team could be empowered to override ordinary processes and chains of command. Placing these officials on the same team would facilitate faster resolutions of problems, allow contractors to deal with one collective authority, as opposed to each individual agency, and reduce the chance that team members will place the good of their respective agencies over the good of the project. Streamlining project decision-making would likely shorten project times by months, if not years.

The mayor should carefully scrutinize his appointments to bodies that have an impact on the budget, such as his selections on PEP. Given the for-cause protections now in place for panel members and its now-mandatory approval before the city council passes the final city budget, the best way for the mayor to minimize the possibility that PEP will withhold its approval is to select members who will remain committed to his agenda. Given PEP’s approval of the FY 2024 education funding estimate three months ahead of the city budget deadline (largely thanks to the votes from mayoral appointees), Adams has thus far largely avoided another PEP-related pitfall.

And though it may seem politically counterintuitive for city leaders to tie their hands on spending, Adams should seek to implement the automatic, rule-based deposits into the city’s Revenue Stabilization Fund that the city chancellor’s office called for last year.[92] Bolstering deposits in strong tax revenue years can substantially lower the risks of out-year budget gaps, service cuts, and local tax hikes during periods of economic uncertainty. Automatic deposits would also signal to the city council and other stakeholders that earmarked deposits are off-limits and cannot be allocated for their preferred spending proposals, thus using local law to build structural fiscal discipline.

That said, it is important to be clear-eyed about the prospects for legislative reform. Over the past decade, the state legislature’s political composition has made it less amenable to reforming the prevailing wage requirement, Wicks Law, city worker pensions, public contracting, or government procurement. Indeed, last year’s expansion of the Panel for Educational Policy and protection for members who vote against the mayor’s wishes signal that the legislature may be laying the groundwork to weaken or even terminate mayoral control in favor of reestablished local school boards.

And some elements that are within the city’s control, such as CBAs for wages and work rules, have essentially become part of city government’s operating structure. Serious attempts to reform the deficiencies found in CBAs, such as conditions of employment that dampen and disincentivize productivity, represent longer-term reform projects. That is partly the result of city politics and partly due to the state Triborough Amendment, which perpetuates the terms of an expired CBA.

Conclusion

Some of the most important budget issues facing New York City will be presented in this report. While it contains helpful recommendations for lawmakers and the Adams administration, it’s necessary to remember the legal strictures that affect the city budget’s flexibility. Navigating the political considerations on the way to reform requires an appreciation of existing arrangements and expectations.

Some reforms face political hurdles, such as changing New York State’s public-sector union laws. Other issues, like the amount of funding that the state sends the city, or the city-state cost-sharing arrangements, are out of the city’s control.

But that doesn’t mean that the city cannot take meaningful and prudent steps to get its budget in order, as this report proves. Careful selection of those who serve as the mayor’s appointees on public boards, better project management and faster approvals for large capital projects, automatic deposits to the rainy day fund, and responsible budgeting of time-limited relief funds are just some of the ways that Mayor Adams can help lead the city to fiscal stability and cement an enduring legacy of fiscal responsibility.

Education Funding in New York City

Ray Domanico

Director, Education Policy; Senior Fellow, Manhattan Institute

The Context

The New York City Department of Education (DOE) occupies an outsize portion of the city’s overall budget. Its $31.1 billion budget is the largest of any city agency.[93] Further, an additional roughly $5.8 billion attributable to DOE is budgeted in city overhead agencies for fringe benefits, pension costs, and debt service.[94] Adding this amount to DOE’s budget indicates that 35.9% of the city’s overall budget is driven by DOE.[95] The most recent available data, from fiscal year 2022, indicate that 46% of the city’s employees are in the department.[96] There is no path to fiscal stability that does not pass through DOE.

Four educational issues will affect the city’s future financial health and the quality of its schools. Whether these impacts are positive or negative will be determined by the extent to which Mayor Adams is able to respond to them responsibly and hold back the worst instincts of many city councilmembers. These issues are:

- Declining school enrollment, particularly in the early grades. Meanwhile, student demographics are changing.

- Temporary pandemic-related federal aid—used by DOE to pay for ongoing program expansion—is running out. City and state funding must replace the aid, or else programs will have to be scaled back.

- Expensive and uneven educational programming for students with special needs. Significant numbers of students are not receiving their full complement of mandated services, and overall academic performance of students with special needs remains low.

- DOE’s union contracts are up for renewal. The teachers’ contract is a large determinant of the city’s overall labor spending.The city must beable to negotiate flexibility in staffing due to enrollment declines.

Overview of the Department of Education’s Budget

Schooling is a labor-intensive proposition. The Department of Education houses 46% of the city’s headcount, and that percentage has grown (Figure 1). Total staffing at DOE grew by more than 10,000 positions, or 7.8%, between 2013 and 2022, when student enrollment decreased by 143,000, almost 15%.[97]

Reflecting the size of DOE’s staff, its pension obligation is huge—over $3.2 billion in 2022, almost 29% of its covered payroll.[98]

Figure 1.

Number of Full-Time Employees in DOE, Compared with Rest of NYC Government

Political Strife amid Reduced Enrollment

The desire to maintain current staffing levels and unused school-building space is the defining issue of educational budget politics in New York City and State. These issues are elaborated on below but are worth mentioning here.

Both the city council and the state legislature are under Democratic control, with progressives in leadership positions. Democrats Mayor Adams and Governor Hochul were elected on more moderate platforms. Both city- and state-level legislators have attempted to limit their executives’ ability to respond to the new reality of lower school enrollment. For instance, the legislature recently mandated lower class sizes in the city and opposes the governor’s modest proposal to remove the geographic limits on charter schools (without changing the cap on the overall number).[99] Also, earlier this year, the city council pressured the mayor to hold individual school budgets harmless for lower enrollment levels.[100]

The political priority of both the city and state legislative bodies is to maintain employment levels in the school system despite plummeting enrollment. This will strain the city’s overall fiscal picture and create inequities within the school system, as lower school sizes will create higher per-pupil spending in schools losing enrollment, at the expense of those schools maintaining enrollment. Further, it will do nothing to alleviate the march of families out of New York State.

Interpreting the Budget and Its Growth

DOE’s budget is constantly growing. In the last 10 years, it has grown by over $12 billion—a higher growth rate (63.7%) than the total city budget (49.1%).[101] Almost $8 billion of that growth occurred in former mayor Bill de Blasio’s last budgets, 2018–22. The current-year DOE budget, Adams’s first, shows a small decline of $231 million from the previous year (Table 1).

Table 1.

NYC DOE’s Share of General Fund Expenditures and Other Financing

($thousands)

There is some confusion about the size of DOE’s budget. One cannot take the gross budget amount of $31 billion divided by 819,000 students in DOE schools (during the 2021–22 school year)[102] to arrive at an estimate of about $38,000 per pupil. As described above, certain public education costs are reported outside the agency budget; but some of DOE’s budget is used to support charter schools, private providers of preschool for three- and four-year-olds, and private schools that serve students with special needs at public cost. A small amount of federal and state funding for private schools also flows through DOE’s budget.[103] The current DOE budget includes at least $6 billion for these private schools and providers, with charter schools accounting for almost half that amount.[104] This “pass-through” money accounts for over 16% of DOE’s fully loaded budget (Table 2).

Table 2.

“Pass-Through” Money in DOE’s Budget, FY 2023 (as of January)

DOE’s budget can also be looked at in terms of broad program areas. As Table 3 shows, spending patterns between FY 2018 and the mayor’s preliminary budget for 2024 (next fiscal year) vary widely.[105]

Allocations for general education (non–special needs) have remained relatively stable since 2018, while spending on programs for students with special needs has grown by over 30%.[106] Reflecting enrollment growth, the “pass-through” amount to charter schools has grown by close to 54%. Mayor de Blasio’s prekindergarten and early childhood programs have more than doubled in cost as they have been expanded.

The growth in federal and state funding is largely explained by the influx of Covid relief funds. The fringe benefits included in DOE’s budget are only for those employees covered by these federal funding streams, and they have grown by over 30%.[107]

The change in spending for Central Administration is somewhat explained by the reclassification of certain functional areas in the budget.

Overall, the Adams administration is proposing a DOE budget of $30.7 billion for the coming year (2023–24).[108] This is a decrease of 1% over the current year and remains subject to negotiation with the city council.

Table 3.

Program Allocation of DOE Budget, FY 2018–FY 2024 (preliminary)

($thousands)

The Issues

Enrollment Decline and Excess Capacity

Ongoing enrollment declines pose the biggest challenge to DOE’s budget. Lower birthrates in the city, outmigration from the city by families, and flight to charter and private schools indicate that the decline in school enrollment will continue.[109]

Despite this, the teachers’ union and their legislative allies have pushed to maintain or even grow school funding, as well as maintain the teaching force at pre-enrollment-decline levels.[110] With the pandemic, individual school budgets were held harmless for enrollment declines during the last two years of the de Blasio administration. As mentioned earlier, in late 2022, the city council pressured the Adams administration to continue that practice, despite schools reopening.[111]

Last year, the state legislature tied increases in state education aid to an across-the-board reduction in class sizes in the city.[112] A city analysis recently found that this mandate will require 7,000 additional teachers and that prioritizing a reduction in class size will lead to diminution of other services.[113] It estimates the overall cost of reducing class sizes to be $1 billion.[114]

The legislature is also reluctant to adopt Governor Hochul’s plan to raise the cap on the number of charter schools in the city. This can be viewed as part of this political protection for the teachers’ union and its members, as drift away from district schools to new charters would increase the need to cut back on the number of union-member teachers in DOE.[115]

Overall, enrollment in grades K–12 in DOE schools is down by 159,661 students in the last 10 years, a drop of 16.6% (Table 4).[116] Charter school enrollment has grown by 68,473 in those same years. Lower birthrates in the city mean that the decline in enrollment is more dramatic in the early grades, and enrollment in DOE kindergarten classes is down by 27% in the last 10 years.[117] The lower kindergarten cohort sizes, which began in 2016–17, are now rippling through the elementary schools. In fact, K–5 enrollment in 2022–23 is 23.5% lower than in 2013–14; that is a loss of more than 103,000 students.[118]

Table 4.

Enrollment in NYC DOE and Charter Schools, 2013–23

Over the last 10 years, combined enrollment in DOE and charter schools declined by 8.8%, but DOE’s budget, which includes charter school funding, increased by over $12 billion, or 63.7% (see Table 1).[119] Fiscal year 2014 was the first year that the city accounted for charter school costs in the way that it now does. In the nine years since the 2013–14 school year, charter school costs increased by 164%,[120] and enrollment increased by nearly 96% (see Table 4).[121] Removing the funds spent on charters from DOE’s budget indicates that non-charter costs increased by 62% while non-charter enrollment decreased by 16.6%.

Racial and Ethnic Differences

The enrollment declines are not uniform across the city’s racial and ethnic groupings. In the 10 years between 2013–14 and 2022–23, the number of black students in grades K–12 fell by 93,595, or 37.2%.[122] Some of that reflects growth in black enrollment in charter schools of 25,360, but the bulk of it is due to lower birthrates and outmigration of black families from the city.[123]

The number of Hispanic students in DOE schools has also declined, but this cohort gained one percentage point as a share of the overall student population (now 41.7%).[124] Asian and white students have also declined in numbers, but at much lower rates, 5% and 14.5%, respectively, than the black student population. As with the general enrollment trends, these figures look starker in the early grades. In 2013–14, 23.2% of all students in grades K–5 were black; today, their share is 17.3%. In raw numbers, there are now 8,700 more Asian than black students in grades K–5. White students in those grades outnumber black students by 797.

While not directly affecting the budget of DOE, these demographic shifts may well alter the politics of education in the city. For decades, DOE has tried to close the achievement gap between black students and other students. The charter schools created as part of this effort are an example of success. In the de Blasio years, efforts to racially integrate schools by curtailing the use of some academic screening caused consternation among vocal white and Asian parents.[125] That effort continues. For instance, the superintendent of District 2 in Manhattan, home to many Asian and white families, chosen to end middle school screening, against the strong wishes of his elected Community Education Council.[126]

Vanishing Covid Aid

In the last three school years, the city has been using federal Covid aid to support school programs. Per IBO testimony, the budgets for FY 2023 through FY 2025 include $3.7 billion of this aid, which will phase out over time.[127] IBO further estimates that after FY 2025, $1.1 billion per year would be required to maintain programs that were established or expanded with the use of the temporary Covid funds. The Adams administration has indicated that it may end the expansion of the city’s prekindergarten program for three-year-old students, which accounts for $393 million of the $1.1 billion.[128] Assuming that the administration is successful at scaling back the pre-K expansion, it will soon still need to find $800 million per year to fill the gap caused by the loss of Covid funding.

Labor Costs and Contracts

The city’s labor agreement with the United Federation of Teachers (UFT) expired in September 2022 and needs to be negotiated. UFT represents more than 75,000 DOE teachers and 25,000 paraprofessionals, as well as other pedagogic employees.[129] Mayor de Blasio’s 2014 contract with UFT has an estimated cost of $5.5 billion over nine years.[130] The 2018 contract, also negotiated by the de Blasio administration, has an estimated cost of $2.1 billion over three years.[131] Uncertainty over the cost of the next contract agreement will hang over budget negotiations between the administration and the council.

Recommendations

There are few easy answers here, but if the city is to maintain its population base, it is going to have to respond to the current reality and to the clear wishes of many parents. That necessarily involves an institutional appreciation for the public benefits that district, charter, and private or parochial schools provide, each in different but complementary ways. Better district schools can coexist alongside more charter schools. High-performing and selective middle and high schools can provide an accelerated learning experience for gifted students without depriving students in other schools of a sound basic education. Other responses include indirect measures like safer streets, including a return to pre-2020 public-safety levels for students walking to and from school.

Improve Building Utilization

Decreased enrollment also means that DOE school buildings are not being used in the most efficient way, particularly because of the de Blasio administration’s resistance to placing new or expanding charter schools in vacant space in DOE buildings.[132] Overall utilization of space designated for DOE programs, not including self-contained special-education programs or charter schools, decreased from 96% in 2015 to 83% in 2022.[133] The citywide figures mask differences across the boroughs (Figure 2). In 2015, Staten Island and Queens were over full utilization; and in 2022, they were at or near full utilization. The other three boroughs saw significant drops in utilization, with each now between 76% and 78% utilization. Meanwhile, the city spends $123 million annually to pay for private leases for charter schools.[134]

Figure 2.

NYC DOE Building Utilization Rates by Borough, 2015 and 2022

Enrollment decline has also exacerbated disparities in the size of local districts. DOE has 32 local community school districts, each with a superintendent, office staff, and elected Community Education Council.[135] The smallest seven districts have average enrollments of 5,537; the remaining 25 average 18,689.[136] Consolidating districts or changing boundaries may require an act of the legislature, as current law contains provisions limiting the city’s ability to change the number of districts in each borough and contains specific prohibitions against moving the boundaries of two specific districts.[137] Still, the small number of students in some districts requires attention for reasons of educational quality and cost-efficiency.

Special-Education Cost and Quality

Beyond the general financial and educational challenges presented by the enrollment declines and the labor contracts, two large program areas should be given serious and outside-the-box attention: how to address the systemic and expensive shortcomings in DOE’s programs for students with special needs; and the ongoing need to address the learning losses that occurred due to reduced opportunities for live instruction during the pandemic.

There are inconsistencies in DOE data on the number of youth classified as students with special needs (Students with Disabilities, or SWD), but the estimates center on 193,000 students (or 20.6% to 20.9% overall).[138] Total costs are also somewhat opaque. The 2022 edition of the New York State Funding Transparency Form, submitted by the city’s DOE, documents school-by-school spending amounts for all students. It calculates per-pupil costs for students without special needs at $13,551; and those with special needs at $33,632, or 248% of the figure for general education.[139] A higher ratio is reported in the 2018 School Based Expenditure Report (the last published) of DOE, which included all DOE funds, including those maintained in central accounts and the overhead costs of individual schools.[140] That report found that students with special needs (in full-time special programs) received services valued at $60,407, or 290% more than students without special needs, who received $20,699.

Nevertheless, special-education services are expensive business in the city’s public schools.

Data on the academic performance of students with special needs are not encouraging. State test results for the 2021–22 school year indicate that only 18.3% of students with disabilities scored at proficient or above in English language arts and 14.4% did so in mathematics (compared with 57.6% and 44.5%, respectively, of non-SWD students).[141] Almost half of students with disabilities scored at the lowest level on the ELA test, and two-thirds did so in mathematics.

The ongoing problems with the city’s special-education program led the city council to require a regular report from DOE on the percentage of SWD who actually receive the services to which they are legally entitled by their Individualized Education Plan.[142] These reports were negative at first, but noted that some of the problems could be due to the lack of complete data.[143] DOE’s data system was not able to accurately identify whether students were receiving their service. The latest report, from autumn 2021, found that only 76% of SWD received their full complement of mandated services in the reporting period; 4% received none of their required services.[144]

The problem is particularly acute with bilingual students with special needs, two-thirds of whom are not receiving their full complement of mandated services.[145] DOE must be able to meet the requirements of a child’s Individualized Education Plan if it intends to reach its goal of reducing the amount spent on “Carter Cases”—court-ordered funds that the city must pay for private school tuition when parents successfully argue that DOE cannot meet their child’s needs. Expenditures on “Carter Cases” regularly exceed the budgeted amount ($446 million budgeted for 2023).[146]

Conclusion

With a budget that totals over a third of the city’s whole, every path to fiscal stability must pass through DOE. In an era of sharply declining enrollment, the Adams administration must find ways to increase the appeal of city public schools for parents. That not only means providing a better-quality education—especially in poorly performing schools and despite the headwinds coming from the city’s powerful teachers’ union—but it also means responding to what parents want, including by addressing learning losses associated with the loss of in-person instruction during the pandemic. Otherwise, it can expect a continued exodus from traditional public schools.

As the administration begins to prepare for smaller class sizes and the costs that accompany them, it should look to create efficiencies by utilizing public school space more efficiently, especially for the new charter schools. The administration should also petition the state legislature to combine local districts to reduce administrative overhead and more closely equalize district sizes. Finally, DOE must do better to educate students with special needs—not only to improve the students’ futures but to save on the hundreds of millions of dollars in private school tuitions that it must pay when public education fails to meet the required standard.

New York City’s Policing Budget

Hannah E. Meyers

Director, Policing & Public Safety; Fellow, Manhattan Institute

The Context

There is perhaps no urban budget issue in the past few years as politically charged as police funding. In New York, as elsewhere, a narrative has gained political prominence over the past few years that police are intrinsically racist and that they are not critical to providing public safety or community stability and order. As in numerous American cities, this has resulted in a decrease in officer funding—in particular, relative to increases in the overall city budget—and a simultaneous investment in “community programs” that do not involve police or that do so only peripherally. The rationale behind these changes has emphasized improving the safety and lives of New York’s black residents and communities, with the implication that this is best done with minimal police participation.

But these funding decisions are not best suited to achieve these aims, as they do not mesh with the realities of crime and community dynamics, which require concrete police involvement. At the same time, a raft of criminal-justice reforms has hobbled prosecution and incarceration, putting an extra onus on police to keep crime at bay through arrests as well as deterrence.

These factors have contributed to a startling increase in crime—one that has disproportionately harmed black New Yorkers. Since debates ahead of this spring’s statewide budget include few promising proposals for policy shifts that will return greater efficacy to the courts, it is doubly necessary to maintain a well-funded police force that has sufficient manpower. This has been borne out by the recent successes of the increased funding toward police units that target gun violence and subway crime. In terms of stability and crime reduction, these units provide more benefit to the city than many of the criminal-justice alternatives to which funding has increasingly been poured.

Finally, greater investments in NYPD and its patrol-focused spending can help stanch a concerning outflow of qualified officers and attract higher-caliber recruits. These investments could also facilitate putting more resources toward training officers in respectful community engagement, which has been shown to help reduce crime and significantly improve community relations.

NYPD Budget Now and Historically

NYPD’s budget rose in fairly steady increments from 1980 through 2020, but relative to the entire city budget, policing investment fell.[147] As Nicole Gelinas writes in her Manhattan Institute paper on NYPD’s budget history, the city’s policing operational budget had fallen from 5.2% of the overall city budget in 1980 to 4.9% by 2022.[148] The police budget has also fallen relative to other city uniformed agencies, which, all told, have remained at about 11% for the past four decades. In that same period, by contrast, the share of the city’s budget devoted to education has grown from 22.5% to 29.6%—a 31% growth in share.[149] The Department of Education now dwarfs NYPD, with a budget roughly six times as large.[150]

NYPD is facing serious staffing issues. The department saw more resignations in 2022 than any time over the past two decades—including at least 1,225 officers who left before even reaching five years of service.[151] More than 3,200 officers left the department last year. According to reporting, the attrition is spurred in large part by the demoralizing anti-cop rhetoric and policies and by the allure of better-paying positions in other jurisdictions.

Spending on uniformed services—fire, sanitation, corrections, and police—grew by 126% over the last four decades, parallel with overall city spending growth (including federal and state grants) but slower than just city-funded growth.[152] In fact, the city’s overall budget increase far outpaced inflation; and ballooning education spending, factoring in the city’s university system, experienced real growth of 193.5%.[153] Nor are the city’s retirement- and health-benefits costs for police, taken together, growing as a share of the citywide benefits budget.

Budget Reductions Inspired by Antipolice Sentiments

In 2020, following antipolice protests, Mayor Bill de Blasio and the city council committed to cutting $1 billion from NYPD’s budget. They did so to explicitly placate antipolice protests and demands rather than as an unavoidable cost-savings measure. The city decided to cancel two of its usual four new classes that year, to eliminate the planned hiring of about 1,160 officers, and shifted enforcement of illegal vending, homeless outreach, and school safety away from NYPD and onto other agencies.[154]

Former council speaker Corey Johnson said of the NYPD budget cut: “I wanted us to go deeper. I wanted larger headcount reductions, I wanted a real hiring freeze. But this budget process involves the mayor, who is not budging.”[155] The New York Times described those who were disappointed with the budget as ranging “from prominent Black activists, elected officials of color like Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, and longtime mayoral allies, like the actress and former candidate for governor, Cynthia Nixon. ‘Defunding police means defunding police,’ Ms. Ocasio-Cortez said. ‘It does not mean budget tricks or funny math.’”[156]

While these budgetary decisions were explicitly motivated by strong antipolice political pressure, they were ultimately tamped to some degree by the realities of the need for police manpower to monitor widespread protests and growing crime. In the end, the NYPD budget fell by only about a half-billion dollars in 2021. This was not, however, inconsequential, as it came in the context of police investments falling relative to the overall city budget, and it marked the first annual decrease since a roughly $18.5 million budget dip in 2004.[157]

The immediacy of rising crime and disorder, coupled with waning passions for antipolice measures, has put less pressure in this budget cycle to reduce police spending. As it stands, the FY 2024 preliminary budget would again represent a drop—of $300 million—but this does not include grants, which have already been incorporated into the 2023 total of $5.7 billion.[158] The FY 2024 number will grow when these are added.

What Does NYPD Spend On?

Since 1980, police department spending has remained largely flat, adjusted for inflation.[159] Relative to other agencies, NYPD’s expense budget is devoted almost entirely to personnel: its corresponding Personal Service budget in 2022 of $5.03 billion covered salaries, overtime, and other wages. The remaining $392 million paid for building leases, heat and power, supplies, equipment, and other costs.[160] For comparison, Personal Service spending accounts for just about 56% of the city’s overall budget.[161] This is not surprising, as NYPD accounts for one out of every six city employees.

NYPD has personnel assigned to 77 precincts, 12 Transit Districts, and 9 Housing Police Service Areas, and other investigative and specialized units. The large majority of spending on these personnel is for uniformed (not civilian) employees. The department divides its budget into 18 program areas. Patrol is the largest of these in terms of budget and headcount and represents roughly half of uniformed police and all precincts. In 2022, this included the 18,621 positions assigned to precincts, 17,271 of these being uniformed.[162]

Still, the civilian share of NYPD employees has grown significantly. In 1981, just 16% of full-time employee expenditures were on civilian employees. By 2021, it was over 29%.[163]

Overtime: An Unpredictable Expense

NYPD also accounts for an outsize amount of NYC overtime pay, another point of criticism directed toward law enforcement. Overtime is very unpredictable, as the demands on any police department may change over the course of the year, depending on crime rates. In 2020, unanticipated widespread, often volatile, protests required a large, uniformed officer response. Indeed, NYPD ended up spending $836 million in overtime that year—despite pandemic cancellations of public events like parades and fairs that normally require extra officer time.[164]

Because of this unpredictability, according to the Independent Budget Office (IBO), NYPD chronically underestimates its future spending on officers working extra shifts, resulting in consistently extending over budget.[165] IBO therefore anticipates that the FY 2024 overtime budget of $452 million will turn out to be insufficient. Roughly the same amount was budgeted for FY 2023, and over 90% of it had been spent just halfway through the fiscal year.[166]

Spending on Alternatives to Policing

Mayor de Blasio and the city council’s plan to reduce the NYPD budget by $1 billion included canceling the July recruit class, major overtime reductions, reducing contracts and non-personnel expenses, and shifting monitoring of illegal vending, homeless outreach, and school safety away from NYPD and onto other agencies.[167] Underlying these budgetary decisions were the guiding principles that police can be safely removed from various functions, interchangeably replaced with nonpolice, and that use of police should be minimized relative to other city employees and contractors. De Blasio stated: “It is time to do the work of reform to think deeply about where our police have to be in the future, where the NYPD has to be in the future.”[168] The budget shifts were couched, broadly speaking, as redistribution to other community services.“We are going to insure summer programming for over 100,000 New York City young people. That is going to be an investment of $115 million. Another $116 million will go towards education, another $134 million will go towards social services and family services in the communities hit hardest by the coronavirus,” de Blasio said.[169] The city planned a half-billion-dollar shift to NYC Housing Authority and NYC Parks youth recreation centers and for broadband expansion.[170]

Beyond these specific one-year budget changes, the past few years have seen broader shifts in overall criminal-justice funding, including several de Blasio–era programs intended as nonpolice, community-focused alternatives to increase public safety. The mayor expanded what had been a one-person role of Criminal Justice Coordinator into the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice (MOCJ) with dozens of staffers.[171] During de Blasio’s first term, between 2013 and 2017, MOCJ’s budget for these services and programs grew 67%, and then by 151% during his second term. MOCJ also funds the contracts for public defenders; these contracts grew by 157% from 2001 through 2020, from $141 million to $363 million.[172] By the current fiscal year 2023, MOCJ’s budget has increased to $813 million.[173] Over roughly two decades, the number of vendors receiving criminal-justice contracts rose by about 235%.

In real-world terms, these budgetary decisions were not about monetary efficiency; they were aimed at changing the criminal-justice system itself, including affecting outcomes for individual criminal defendants. Some of these plans revolved around de Blasio’s cart-before-the-horse commitment to close NYC’s main jail facility, Rikers Island. As described by IBO:

The budget for public defenders and community-based criminal justice system programming grew considerably from 2001 through 2020, with most of the increase occurring after 2017. [MOCJ] undertook several reforms to the system during this period in order to curb jail stays and expand alternatives to incarceration, with the intention of ultimately closing and replacing Rikers Island. This period of MOCJ’s growth was primarily driven by increased spending on contracts for community-based organizations. These contracts are for a range of services, including supervised release and other alternatives to detention and incarceration, re-entry services, victim services, and other programs.[174]

The Department of Probation also received greater funding, including toward its functions overseeing or collaborating on various mentoring programs, restorative justice efforts, and other specialized programming for both youth and adults under supervision. Spending on contractual services in these areas rose steeply under de Blasio, more than doubling from 2013 through 2020.[175]

In 2014, Mayor de Blasio launched the Mayor’s Action Plan for Neighborhood Safety (MAP), a far-reaching approach to reduce violent crime in and around the 15 most dangerous public housing developments in the city. While NYPD is a listed partner in MAP, it is explicitly not driving the program nor is it a central pillar of it. Similarly, MOCJ has run Atlas, which seeks to reduce cycles of violence through community-based therapy.[176]

According to IBO, the NYPD’s and the Department of Corrections’ share of the criminal-justice system budget fell from 84% in 2011 to 79% in 2020. At the same time, the budget share devoted to alternatives to detention and incarceration increased from about 6% to 8%.

This trend continued after de Blasio’s administration, even though recent reporting suggests that Mayor Eric Adams may be switching some program oversight away from MOCJ.[177] The city’s 2022 Executive Budget included increases in community-based programming for antiviolence programs, mental-health initiatives, and alternatives to incarceration. The MOCJ budget saw an expansion of the Cure Violence program (which uses contracted “credible messengers” to try to prevent violent crime) and Advance Peace Model[178] (which focuses on nonpolice gun interventions), as well as initiatives agreed to as part of the negotiations around the city council’s approval of the construction of borough-based jails, known as the Points of Agreement. The NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene also received increases for several mental-health initiatives, including de Blasio’s NYC Safe.[179]

Legislative Changes and Rising Crime

NYPD is just one of three categories in the city’s “administration of justice” spending, along with Corrections and Courts. But while all three have additional financial needs as the result of criminal-justice reforms over the past few years, the reforms have disproportionately hobbled the efficacy of Corrections and Courts. That leaves the police as an even more critical agency in a time of rising threat to New York residents.

Over the past few years, New York State passed several criminal-justice reforms that have contributed to the rise in crime. Raise the Age, enacted in 2017, reduced consequences for 16- and 17-year- old criminal offenders.[180] Bail reform, passed in 2019, makes it impossible for judges to detain categories of defendants pretrial even if they are dangerous, and it requires that judges set the “least restrictive” release conditions that reasonably ensure that defendants return to court.[181] Discovery reform, also passed in 2019, created such a heavy compliance burden on prosecutors that they were forced to triage cases, dismissing many times more viable cases.[182] And Less Is More, enacted in 2021, changed the rules around revoking parole, greatly reducing the number of both technical and criminal parole violators being returned to jail.[183]

The sum of the impact of these reforms is that while police are continuing to make arrests, offenders are not being incapacitated by prosecution and incarceration nor are they being deterred by the likelihood of either. The chances of seeing any meaningful legislative shift in the state’s spring budget appear low, since the NYS legislature has been staunchly unwilling to have a probing discussion about the actual impacts of these laws on public safety.

Since its nadir around 2017, NYC crime has risen, first slowly and then leaping up in 2020. This increase has been both in serious violent crime and in street-level disorder. In 2022, there were over 30.7% more index crimes in NYC than in 2019. This represented 55,000 more victims, including 30,000 felony victims.[184] Some offenses, like car theft, were up over 150%. And while both shootings and murders were slightly down from 2021 peaks, there were nearly 70% more shooting victims and over 30% more murders in 2022 than in 2019.[185] The victims of this rising violence are disproportionately black and Hispanic and disproportionately young: juvenile shootings and homicides have not fallen, even while the overall rates have.[186]

Nonviolent crime is way up, as well: petit larcenies have risen 28% since 2019, and grand larcenies rose 18%.[187] Quality-of-life crime has also increased with a widespread rise in homelessness, open drug use, and fare evasion.

Recommendations

Invest in Police Officers, a Proven Public-Safety Investment, Not the Alternatives

Police have been repeatedly proven to reduce crime and public disorder.[188] Research indicates that each additional police officer added to a large American police force abates approximately 0.1 homicides.[189] And the per-capita effects of this improvement are twice as large for black victims as they are for white victims. In the past few years, the city has spent an enormous amount on rhetoric-heavy public-safety alternatives rather than on uniformed officers—with fewer measurable gains for New Yorkers in general or for black residents, in particular. Mayor Adams should push to refocus maximum funding toward NYPD officers at the expense of less proven alternative programs.