Mental-Health Trends and the “Great Awokening”

Executive Summary

In material terms, today’s young Americans are arguably the most privileged generation in the country’s history. The battlefields of war are distant memories, and destitution, for most, is a specter from another era. In their basic needs—food, shelter, education—they are more secure than ever before. And yet, beneath this veneer of privilege and prosperity, there is an unsettling paradox. Despite these material advantages, today’s youth—especially young women—may very well be the most mentally distressed generation in American history. Rates of reported depression, anxiety, and other forms of psychological distress among young Americans have soared over the past decade, while rates of intentional self-harm and suicide are at, or have surpassed, previous highs.

What has caused this sudden deterioration in young people’s mental health remains contested. Some blame the rapid spread and adoption of smartphones and social media, which subject young people to constant, widespread social pressures.

But others argue that the evidence for this claim is wildly overstated; that the relationship between social media and mental health is generally modest, not always negative, and not obviously causal; and that decreases in young Americans’ mental health are likely attributable to other underexamined factors. As they see it, the hoopla over social media is just the latest in a series of moral panics about new technologies and media allegedly harming the youth.

Though this report will engage in this ongoing debate, it cannot, nor does it seek to, definitively resolve it. Instead, it offers a theory that attempts to reconcile the conflicting perspectives while shining a light on and explaining relevant but generally overlooked patterns in the data. In short, the effect of social media on mental health is not uniform; whether social media is psychologically harmful depends on both the particular psychological traits of the user and on the broader sociocultural environment.

Importantly, recent increases in mental ill-being are significantly larger not only for girls than for boys but also for self-identified liberals compared with conservatives. While the sex differences have received ample attention among researchers, those between ideological groups have not. This is unfortunate because the two phenomena are likely related. As this report will discuss, females and liberals tend to rank higher than their male and conservative counterparts in certain personality traits that are associated with greater susceptibility to internalizing symptoms. These symptoms are characterized by inwardly directed emotional distress, including feelings of sadness, worry, and fear, which can manifest as conditions like depression and anxiety. Moreover, these traits may also influence the frequency of social-media use, the type of content that people seek out or attend to, and the type and strength of their emotional responses to different kinds of social-media content.

For example, individuals who score higher in neuroticism and lower on conscientiousness are at greater risk of excessive or addictive social-media use and of engaging in habits such as“doomscrolling,” which can harm productivity and displace time spent on activities conducive to psychological health, such as sleep, exercise, and face-to-face social interaction. Other traits, including aesthetic and emotional openness, empathic concern, and justice sensitivity—which are also more common among girls and liberals—can also intensify negative emotional responses to distressing social-media content, potentially worsening psychological well-being over time.

Building on this foundation, the theory proposes that the net impact of social media on mental health is not uniform but varies significantly as a function of individual differences in underlying personality profiles. Accordingly, it holds that “psychologically vulnerable” personality profiles tend to be more prevalent among girls and liberals and that such groups thus experience more negative effects from social-media use.

The impact of social media can also be influenced by the broader sociopolitical and media environment. For example, the “Great Awokening” of the last decade coincided with massive increases in the output of news content centered on social-justice issues, such as racial and gender inequality and discrimination. For individuals whose psychological profiles heighten sensitivity to such issues, the relentless flow and frequent consumption of this content can potentially increase emotional stress and exacerbate mental-health issues.

Outline of Report

This report is divided into four main sections:

Section 1 presents several sources of time-series data that reveal a seemingly unprecedented rise in rates of self-reported mental-health issues and internalizing symptoms (e.g., anxiety, depression) among young Americans aged 18–21, with the increase being particularly pronounced among females. It then examines similar trends in suicide rates and incidents of intentional self-injury among youth and young adults, alongside declines in self-esteem, life satisfaction, and increases in loneliness among high school seniors. This section explains why these trends cannot be attributed solely to overreporting, given that time series of self-reported internalizing symptoms, self-esteem, and life satisfaction are closely correlated with trends in suicide rates over time. Section 1 also shows that the rise in psychological distress is significantly more pronounced among self-identified liberals than conservatives of both sexes. Additionally, it provides evidence suggesting that trends in psychological distress among non-liberals—and ultimately, national teenage suicide rates—tend to follow those observed among liberals. These data raise important questions regarding the intersection of mental well-being and political ideology that will be explored in subsequent sections.

Section 2 considers short- and long-term drivers of recent mental-health trends and ideological divergence therein. It begins by outlining what would be required of any causal theory of these trends; and it argues that accounts implicating the emergence and spread of social media and smartphones do satisfy these theoretical demands, even as there is reason to doubt that this is the sole cause. In doing so, it brings to bear more than a dozen time series that track trends in social-media and smartphone use among teens and young adults, all of which show that increases in this behavior both temporally precede and coincide with those in mental ill-being. While acknowledging that the empirical literature regarding the negative mental-health effects of social media contains mixed findings, the section proposes that the size and direction of such effects greatly vary as a function of individual predispositions. The nature of that variance is the focus of subsequent sections.

The section concludes by discussing the role of religious decline, noting that this trend—far more pronounced among young liberals than conservatives—may have further eroded psychological resilience, thereby intensifying the impact of modern digital life. This exploration of religious and ideological differences provides a crucial backdrop for understanding how broader sociocultural shifts may be influencing the mental health of various demographic groups.

Section 3 makes the case that the negative mental-health effects of social media are concentrated among those with predispositions that heighten psychological vulnerability. It begins by outlining the mechanisms through which social media is expected to negatively influence mental well-being. It then highlights a series of broad and narrow personality traits (e.g., neuroticism, conscientiousness) and facets (e.g., emotional openness, justice sensitivity) that are not only associated with poorer mental-health outcomes but also frequent and excessive social-media and smartphone use, the kinds of social-media content individuals seek out and consume, and the (negative) emotional response to such content.

The section connects these findings to the sex and ideological differences in mental health by showing that these personality risk factors tend to be more common among females and liberals. It also presents evidence that rates of frequent social-media use and the diversity of used social-media platforms tend to be greater among girls and liberals than boys and conservatives. More importantly, it presents evidence that frequent social-media use has a larger negative effect on the mental health of the former than the latter two groups. It further finds that girls and liberals are also more likely than boys and conservatives to report encountering content on social media that makes them feel depressed and lonely—differences that are substantially explained by differences in broad personality domains, such as neuroticism, conscientiousness, agreeableness, and openness.

Crucially, the section addresses the question of causality: Does liberal and left-wing ideology lead to mental-health problems, or do these ideologies disproportionately resonate with and attract those with psychological vulnerabilities? Leveraging results from cross-lagged panel models (CLPM), random-intercept cross-lagged panel models (RI-CLPM), and vector error-correction models (VECM) of time-series data, it suggests that while both directions are plausible, the evidence leans more strongly toward the latter—namely, that poor mental health tends to shift individuals toward more liberal ideological self-identification rather than the other way around. However, the section also argues that ideological differences in the mental health–social media relationship cannot be wholly divorced from the broader political and media environment in which they occur. In particular, large and rapid increases in the media salience of social-justice-related topics like racial and sex-based discrimination and inequality, along with the presidency of Donald Trump, are likely to have exacerbated ideological differences in mental-health outcomes.

Section 4 concludes by synthesizing key insights from the report and reflects on the broader implications of the findings. It acknowledges the complexity of the relationship between social-media use, mental health, and political ideology, suggesting that while social media likely plays a role in the recent decline in mental well-being, this impact is mediated by individual psychological vulnerabilities and the broader sociopolitical environment. The section argues that mental-health challenges may drive individuals toward more liberal ideologies and that, while social media amplifies this trend, it is not the sole factor. The discussion also highlights the limitations of this report and existing research more generally, emphasizing the need for more rigorous studies to draw definitive causal conclusions.

The section discusses potential policy implications, cautioning against blanket regulations on social media and advocating for more nuanced interventions that take individual differences into account. It concludes by stressing the importance of addressing broader sociocultural trends that may be contributing to the observed mental-health declines, suggesting that these trends, alongside social media, play a significant role in shaping the mental well-being of today’s youth.

Section 1: Trends in Mental Health Among Young Americans

1.1 Trends in Self-Reported Negative Mental-Health Symptoms

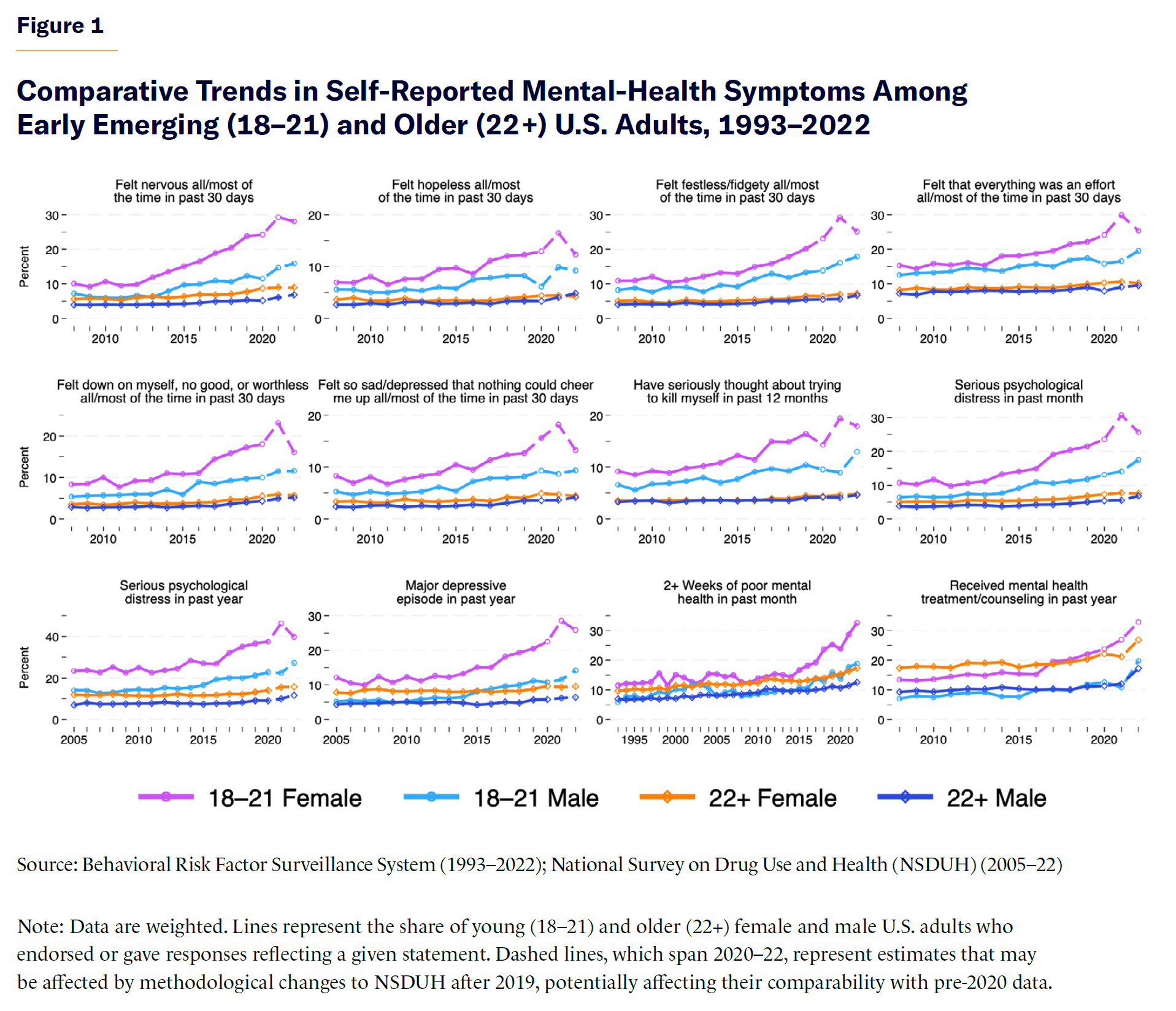

My analysis begins with the most abundant category of available data: self-reported negative mental-health symptoms among U.S. adults. Figure 1 presents a compilation of 12 time series of responses to measures of mental health, gathered from two large surveys of the noninstitutionalized U.S. adult population. A consistent trend emerges across these series: over the past decade, young adults[1] (for this report, those aged 18–21) have reported symptoms of depression and other mental-health issues at an accelerating rate, far outstripping their older counterparts. For example, data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) show a pronounced increase in the share of young adults who report experiencing poor mental health for two weeks or longer in the past month—from 11% in 2011 to 25% in 2022, the highest since the survey’s introduction in 1993. Although this metric also showed an increase among older adults (aged 22 and older) during this period, the rise was more modest, at only 3 percentage points.

It is also clear that poor mental-health outcomes have risen disproportionately among young adult women, at least in absolute terms. For instance, while the percentage of young men reporting poor mental health for two weeks or longer in the past month increased by nearly 10 percentage points (from 9% to 19%) across the 2011–22 period, the increase was 19 points (14% to 33%) among young women. A similar pattern emerges in data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH): between 2011 and 2019, the share of young men reporting significant psychological distress in the past year increased by 7 percentage points (from 14% to 21%). In contrast, the increase among young women was 14 points (from 23% to 37%). While methodological changes to NSDUH during and after 2020 complicate comparisons with post-2019 estimates (hence the dashed lines from 2020–22), these figures stood at 40% for young women and 27% for men in the most recent (2022) survey.

Unfortunately, public-health agencies did not consistently survey mental health using the same measures until the early 2000s. This raises a pertinent question: Are the recent increases in reported symptoms an unprecedented historical shift? It could be that these trends are merely the latest wave in a long-standing cyclical pattern, similar to the fluctuations in suicide rates over time (which will be discussed later). If this were the case, we would expect rates of negative mental-health outcomes to eventually revert to earlier levels.

To mitigate the recency bias in the data and extend the analysis further back in time, I amalgamate mental-health indicators from various time frames into a singular factor-weighted Mental Health Index. Using a software algorithm[2] designed for this purpose, I’ve integrated 85 distinct time series of responses to mental-health indicators (primarily of depression and anxiety), each having been polled at least three times between 1993 and 2022 to meet the algorithm’s requirement for a minimum of three distinct measurements.[3] All told, the resulting index accounts for 62% of the variation across the 85 series for young and older adult women, respectively, while accounting for 51% of the variation for young men and 54% for older men.[4]

Annual scores on this index, visualized in Figure 2, can be roughly interpreted as the average percentage of respondents reporting adverse mental-health outcomes for each year. Confirming the observations from the lone BRFSS series in Figure 1, these scores reveal that the reporting of negative mental-health symptoms among young adult Americans—both men and women—is now higher than at any point since at least 1993. The data also indicate that reporting rates were relatively stable until the early to mid-2010s,[5] a period marked by massive increases in smartphone and social-media adoption, as will be discussed later.

Although this report focuses primarily on the U.S., Figure 3 illustrates similar patterns in mental-health trends across other Western countries. As with the U.S., increases in negative mental-health outcomes are more pronounced among girls than boys. While the data available for these countries may not be as comprehensive as that for the U.S.—and while there may be countries where these patterns diverge—this suggests that the mental-health challenges faced by American youth and young adults are not unique to them. Instead, they reflect a broader phenomenon that is affecting at least some of their peers in other parts of the developed world.

1.2 Trends in Suicide and Intentional Nonfatal Self-Injury Rates

The recent surge in reported negative mental-health symptoms among young adult Americans is unparalleled, at least in the past 30 years—but does this necessarily mean that today’s young Americans are genuinely more mentally troubled than their predecessors? Alternatively, could it be that young adults’ mental health is not markedly different from that of previous generations, but that they are now more likely to report less severe symptoms?

One way to assess what role, if any, overreporting plays in explaining these trends is to examine rates of suicide and intentional nonfatal self-harm. Data from CDC, depicted in Figure 4, however, do indeed reveal a notable rise in these outcomes.

Although suicide is generally far less common among women than men, it’s notable that suicide rates for females aged 10–19 have consistently increased each year since 2010. By 2014, these rates surpassed their previous recorded high of 2.6 suicides per 100,000 in 1988. This trend then continued in the years that followed.

But while suicide is more prevalent among men than women, the reverse is true when it comes to intentional nonfatal self-injuries, such as cutting and burning. Although relevant data are available only from 2001 onward, they show that self-injury is not only more frequent among women in general but has also increased among females aged 10–19 in every year since 2010, peaking in 2022.

Males aged 10–19, by contrast, experienced a decline in suicide rates from 1995 to 2008. However, recent years have seen a return to the peak rates of the late 1980s and early 1990s, with some years even exceeding those earlier highs. Additionally, although the youngest boys (ages 10–14) have consistently had much lower suicide rates than their older counterparts, their suicide frequency in recent years is historically unprecedented, even if still small in absolute terms.

While CDC has reported data for user-specified (as opposed to fixed five-year) age groups starting only from 1999, very similar patterns in suicide and self-harm rates are observed for young adult (orange line, Figure 4) women and men. In fact, the suicide rates for both women and men in this group exceed all the others. As shown in Figure 5, suicide rates are also highly correlated with scores on the Mental Health Index.[6]

These findings have important implications for recent trends in the reporting of negative mental-health outcomes among young adults and youth.

First, the strong correlation between survey responses to mental-health measures and suicide rates over time suggests that the significant increases observed in the Mental Health Index could be part of a long-term cyclical pattern. In other words, if it were possible to extend the Mental Health Index series further back in time than 1993, it’s conceivable that similar, though perhaps more moderate, increases would have been observed in earlier decades.

Second, the strong correlation between surveyed mental health and suicide rates in the twenty-first century, especially among young adult women, makes it unlikely that the increases in reported symptoms of depression and anxiety can be attributed solely to overreporting or methodological changes in survey design. Moreover, as will be covered in the next section, overreporting would not adequately explain the coincident emergence of similar trends in attitudes closely associated with mental health, such as self-esteem and life satisfaction, or why these trends are more pronounced among self-identified liberal than conservative youth.

1.3 Trends in Self-Esteem, Life Satisfaction, and Loneliness

Few surveys consistently track mental health over time, and even fewer do so specifically for youth. One notable exception that does so, albeit indirectly, is the Monitoring the Future (MTF) survey. While it does not use clinical or conventional measures of mental health, MTF has regularly evaluated factors such as self-esteem, life satisfaction, self-derogation, and loneliness among 12th-grade high school students since the late 1970s. Although these are distinct constructs, they are highly correlated with depression and other mental-health issues.[7]

Figure 6 presents a compilation of 16 different time series that track measures of self-esteem, life satisfaction, self-derogation, and loneliness among 12th-graders, segregated by sex. Collectively, these time series reveal historically unprecedented decreases in self-esteem and life satisfaction and significant increases in self-derogation and loneliness among 12th-graders of both sexes over the past decade. For instance, from 2011 to 2021, the shares of 12th-graders agreeing with the statement that “life often seems meaningless” nearly tripled among girls (from 12% to 29%) and nearly doubled among boys (13% to 23%).

Yet Figure 7 suggests that the magnitude of sex differences in these items pales in comparison with the differences observed between political-ideological groups—namely, liberals and conservatives.

To provide a clearer comparison between the sex and ideological differences, I redeploy the algorithm used earlier to consolidate each group’s time series into factor-weighted “Psychological Distress” (PD) indexes. Annual group PD index scores[8]—representing the average percentage of respondents showing signs of low self-esteem, life dissatisfaction, self-derogation, and loneliness—are illustrated in the middle panel of Figure 8. Across both sexes, the data show that increases on these indicators are, on average, more pronounced among liberals than conservatives. The chart displayed in the right panel further reveals that the difference in scores between liberal and conservative 12th-graders remained, on average, below 10 points until 2013. In that year, the gap expanded to 12 points. Since then, nearly every subsequent year has witnessed at least a slight increase in this disparity. For perspective, the scores for 12th-grade girls and boys collectively never diverged by more than 6–7 points prior to 2015. As of 2022, the difference is 9 points, a gap that is notably smaller—less than half—than that between liberals and conservatives.

Given the relationship between these indicators and mental health, it should come as no surprise that ideology is also increasingly correlated with the rates at which 12th-graders seek mental-health treatment. The right panel of Figure 9 shows that, during 1982–2015, self-identified liberal 12th-graders were, on average, 3 points more likely than conservative students to have visited a doctor or other health professional for mental-health concerns in the past year. Notably, this ideological gap never surpassed 7 points until 2016. By 2021–22, however, the difference had widened dramatically, with liberal students 13–17 points more likely than conservatives to seek mental-health support.

Because MTF data are available for twice as many years as the adult mental-health series, we can now more reliably examine both the strength and direction of associations between PD and suicide rates over time. Accordingly, Figure 10 illustrates and reports the bivariate correlation between each group’s PD series and the suicide rates for females and males aged 15–19—which is the closest group in the CDC data to the typical ages (17–19) of high school seniors.

We observe strong positive correlations between PD scores and suicide rates among all females (r=0.833), including for self-identified liberal (r=0.830) and conservative (r=0.827) females. Although not shown, year-to-year changes in the female PD index are also significantly positively correlated with year-to-year changes in female suicide rates (Δr=0.294, p=0.047). However, these correlations provide only part of the picture.

Tables B.1–B.3 in the online Appendix present the results of a Toda-Yamamoto causality test, which determines the direction of causality between two time series, even when the data are nonstationary, as is the case here. The results, which are not sensitive to lag length, indicate that increases in the PD index for females overall—and specifically for liberal females—significantly predict increases in female suicide rates in the subsequent year, while suicide rates themselves do not predict future PD scores.

For conservative females, however, a different pattern emerges. Suicide rates tend to precede increases in their PD index. This discrepancy suggests that distress among female liberals may serve as a leading indicator of broader mental-health trends, with changes in female conservative PD following those among female liberals. Results from a lagged-dependent variable model (online Appendix Table B.4) further support this, showing that only the PD index for liberal females significantly predicts female suicide rates.

The patterns for males show some similarities but also key differences. Increases in male PD tend to follow increases in female PD, and as with females, increases in male conservative PD often follow increases in male liberal PD, which, in turn, follow trends in female PD (and especially liberal female PD). However, while male PD is correlated with suicide rates, this relationship is weaker than it is for females and weaker still for conservative males. Importantly, the data show no evidence that increases in male suicide rates follow increases in the male PD index. Instead, as with PD, male suicide rates tend to follow trends in female suicide rates.

The observations have two important implications. First, the trends in direct indicators of young adult mental health (discussed in Section 1.1) are mirrored in variables closely linked to mental health. Just as rates of depression and anxiety symptoms have surged among young adults over the past decade, self-derogation and loneliness among high school seniors have reached record highs, while self-esteem and life satisfaction have fallen to record lows during the same period.

Crucially, these trends are much more pronounced among liberals than conservatives of both sexes. Although sex differences are also apparent, they are much smaller in magnitude than those between ideological groups.

Second, the trends captured by the PD index correlate with those in suicide rates across time, though this relationship is much stronger for females and liberals, particularly female liberals. If these trends in mental health were merely due to overreporting and methodological changes, such associations would be difficult to explain. Notably, increases in female liberal PD consistently precede increases in suicide rates among 15–19-year-old females, as well as increases in the PD scores of other groups, including those of female conservatives. In turn, increases in suicide rates for girls tend to precede increases for boys, while increases in the PD scores of conservative males tend to follow increases in those for liberal males. Taken as a whole, the data suggest that trends in psychological well-being among liberals, particularly female liberals, may be a bellwether of broader mental-health issues that eventually surface in other demographic groups.

More generally, the pattern of ideological differences in mental health sheds light on sex differences in reported negative mental-health outcomes that were discussed in Section 1.1. As Figure 11 shows, 12th-grade females have, in recent years, become increasingly more likely than males to identify as liberal, while boys have become increasingly more likely to identify as conservative. Thus, growing sex differences in the reporting of negative mental-health symptoms may be at least partly attributable to, or perhaps even drive, girls’ increasing overrepresentation on the left side of the political spectrum. Consistent with this, the online Appendix reports results from a VECM, which reveals a significant long-run unidirectional relationship between the female PD index and the share of females identifying as liberal, with increases in female PD predicting subsequent increases in female rates of liberal self-identification.

These findings also raise important questions regarding the interplay between mental health and political ideology. Is there something inherent in left-leaning political beliefs that predisposes individuals to mental-health challenges? Alternatively, are those who experience mental-health difficulties more naturally drawn to left-wing political ideologies?

Section 2: Explaining Youth Trends in Mental Health

There is no consensus in the scientific literature about the causes of recent trends in youth mental health. However, any viable causal theory must satisfy at least three important criteria. First, it needs to explain the timing of the increases in negative mental-health outcomes—specifically, why these trends became apparent at the beginning of the last decade and not earlier. Second, it must account for why these increases were most pronounced among young women/girls and liberals, and less so among men/boys and conservatives. Third, it should be able to explain the apparent occurrence of similar trends in other countries.[9]

Given these criteria, one popular explanation, which arguably stands out for being able to address all three requirements, centers on the meteoric rise of new information technologies—most notably, social media and smartphones. As we will see, the adoption of these platforms not only surged at the beginning of the last decade, but the extent of their use has also varied across different demographic groups, including young women/girls and liberals. Moreover, due to average differences in psychosocial variables, there are reasons to believe that the use of such technologies differentially affects the mental health of these groups, potentially explaining their worse mental-health outcomes.

2.1 The Social-Media and Smartphone Boom

As shown in Figure 12, the share of Americans who own smartphones, connect to the internet through their phones, and frequently use social media has risen steadily over the past two decades, especially among younger Americans. For example, the share of Americans aged 18–21 who reported using social media at least several times a day grew by more than 30 percentage points—from 14% to 45%—compared with an increase of just 10 points (from 6% to 16%) among older adults (22+) in the five-year period between 2006 and 2011. Similarly, the share of young adults using Instagram (launched in late 2010) surged from 25% in 2012 to 64% in 2014. Meanwhile, among those aged 12–17, the percentage reporting being “almost constantly” online nearly doubled, from 23% in 2014 to 42% in 2018.

Figure 13 shows that the share of U.S. high schoolers who reported engaging in three or more hours of recreational “screen time” (e.g., using social media, watching videos, playing video games) jumped significantly, from 25% to 41%, during 2009–13. By 2021, this figure had risen to 73%, though revisions to this question’s response options that year complicate comparisons with earlier years.

Crucially, as highlighted in Figure 14, these increases in smartphone and social-media use both precede and coincide with an uptick in negative mental-health outcomes among young adults (as shown on the left y-axis). Of course, this correlation does not necessarily imply causation. While economic downturns, such as the Great Recession of 2008–09, do not appear to be a contributing factor,[10] we cannot rule out other potential causes unrelated to technology—factors that may account for mental-health trends not only among young Americans but also among their counterparts in other countries.

What can be said, though, is that a technology-centered theory satisfies the three explanatory criteria outlined earlier. Moreover, at the individual level, a large number[11] of studies have documented statistically significant relationships between negative mental-health outcomes and social-media and smartphone use. While most of these studies are cross-sectional—and thus do not permit causal inference—significant relationships have also been observed in both longitudinal[12] and (quasi-)[13] experimental[14] research.

At the same time, research on the relationship between social-media/smartphone use and mental well-being is diverse and not always in agreement. Meta-analyses[15] of relevant studies generally find a modest relationship between social-media/smartphone use and mental well-being,[16] if statistically significant, leading some skeptical researchers to question whether a meaningful relationship exists at all.[17] Adding to this complexity, some studies find that social media can actually enhance well-being, further underscoring the variability of results.[18]

This variability in findings is likely due not only to methodological differences but to the fact that the mental-health effects of social-media/smartphone use are more negative or positive for some users than for others. More specifically, as will be elaborated upon in the next section, certain individual predispositions increase the likelihood and frequency of experiencing negative effects from engagement with these technologies. These predispositions, as it turns out, tend to be more common among girls and liberals than boys and conservatives.

2.2. Decline of Religion

Before delving into the theoretical mechanisms by which digital media might affect mental health and the predispositions that could moderate this relationship, it is crucial to highlight another significant trend that likely influences youth mental health: the decline of traditional religion.

Traditional religious faith and practice are on the decline[19] across much of the world, and the U.S. is no longer a “quasi-exception”[20] to this pattern. While this trend is evident among U.S. adults overall, significant downward shifts in religiosity are also readily apparent among America’s youth. Given the well-documented positive[21] effects of religiosity on mental well-being,[22] these trends could have important implications for understanding the observed declines in mental health.

For thousands of years, religion has served as a bulwark against the psychological burdens of existential anxiety and hopeless nihilism. In fact, research suggests that religion’s ability to provide existential meaning and hope is a primary mechanism by which it promotes psychological well-being and protects against conditions like depression.[23]

Religion also provides membership in a community of shared values and, concomitantly, access to congregational support systems in times of need. Congregational support, in turn, has been linked to reduced psychological distress,[24] depression symptoms,[25] and risk of a range of psychiatric conditions.[26]

While secular substitutes certainly exist, the psychosocial benefits of traditional religious belief and belonging may not be easily replaced or replicated. The decline of traditional religion in the U.S. could thus be contributing to the emergence of generations with fewer psychological and in-person communal resources for coping with the stressors that accompany—or are amplified by—our increasingly interconnected and digital modern world.

Importantly, traditional religiosity has declined more for some young Americans than for others. As shown in Figure 15, the decreases over time in the importance that American 12th-graders ascribe to religion (left panel) and in their frequency of attending religious services have been much steeper among self-identified liberals than among conservatives of both sexes. In fact, the rates for these outcomes among conservatives today are not much lower than they were in the 1970s.

Clearly, trends in religiosity predate the rise in youth digital-media use and the associated shifts in mental health by at least several years. However, the claim here is not that the decline in religiosity directly catalyzed these developments. Instead, I’m suggesting that reduced religiosity could very well heighten individuals’ susceptibility to the potential negative mental-health effects of digital media.

Accordingly, at least part of the reason that increases in negative mental-health outcomes have been greater for young liberals than conservatives could be that liberals have experienced a more pronounced decline in traditional religious involvement and, consequently, have relatively fewer psychosocial resources for coping with the stressors of modern life. This account is supported by the results of a supplemental analysis[27] (see online Appendix), showing that measures of religious importance and service attendance explain anywhere from a quarter to just under half of the differences in self-esteem, depressive affect, self-derogation, and loneliness between liberal and conservative 12th-graders. Recent surveys of U.S. adults also show comparable moderation of liberal–conservative differences in mental-health indexes when religiosity is held constant.[28]

However, sizable liberal–conservative mental-health gaps persist even after accounting for religiosity, which suggests that differences in religiosity may be only a small part of the story. It’s possible that both religiosity and ideology are influenced by, or stem from, other core psychological and behavioral variables. As discussed below, these variables may not only shape a person’s social-media engagement but also determine the psychological impact of that engagement.

Section 3: A Theory of Variability in the Mental Health–Digital Media Relationship

3.1 Theoretical Mechanisms of Social Media’s Negative Mental-Health Effects

Several mechanisms have been posited to explain the purported negative effects of social media on mental health. These include but are not limited to:

- Upward social comparisons: Social media vastly increases opportunities for individuals to compare themselves with others who appear to be “better off.” For example, apps like Instagram readily bombard users with idealized depictions of others’ lives. Such upward social comparisons have been linked to feelings of inadequacy and envy,[29] lower self-esteem,[30] and depressive symptoms.[31]

- Cyberbullying: Social media expands the universe of people who can pass judgment on us, from close friends, family, and community members to countless individuals worldwide. Within this vast audience, the platform’s anonymity allows users to mock and disparage others with relative impunity. Repeated experiences of “cyberbullying” can potentially erode self-esteem and contribute to or exacerbate mental-health issues like anxiety and depression.[32]

- Exposure to distressing content: Social media amplifies exposure to distressing news and information, such as instances of human suffering, social injustice, and politically divisive or alarmist rhetoric. In fact, several studies have indicated that content evoking negative moral emotions, like moral outrage, tends to be more frequently shared and achieves higher visibility on these platforms.[33] This prevalence of negative stimuli can contribute to “doomscrolling”—habitually seeking out and consuming such negative information—which, in turn, can elevate psychological distress and adversely affect mental well-being.[34]

- Time displacement: Excessive engagement with social media can lead to lifestyle disruptions, displacing time that might otherwise be spent on health-promoting activities and face-to-face social interaction. For instance, heavy social-media use has been linked[35] to poorer sleeping patterns (e.g., shorter sleep duration, longer sleep latency, more mid-sleep awakenings) and reduced physical activity,[36] both of which can undermine mental well-being.[37] Additionally, spending less time engaging in in-personal social interactions may ultimately lead to feelings of loneliness,[38] which are predictive of negative mental-health outcomes.[39]

- Social contagion effects: Social-media platforms, particularly ones like Instagram, can amplify and spread emotional states across vast networks of users.[40] Not only do these platforms facilitate the subconscious transmission of emotions like happiness or sadness, but they also provide a space where graphic content, such as self-harm, can be readily accessed.[41] Recent research has highlighted a concerning association between exposure to such graphic depictions of self-harm on social media and increased risks of suicidal ideation, self-harm, and emotional disturbances among vulnerable users.[42] Furthermore, certain online communities and influencers may inadvertently glamorize or romanticize mental-health conditions, leading[43] some users to self-diagnose[44] or misinterpret their everyday emotional fluctuations. Individuals may also mimic the behavioral symptoms they observe online, which could potentially become chronic, even in the absence of an underlying psychiatric condition.[45]

For all these mechanisms, however, the extent to which social-media use is psychologically harmful is likely to vary based on individual predispositions. In what follows, I discuss the role of broad and narrow personality traits that may not only moderate the potential negative mental-health effects of social media but also help explain the differences in mental-health outcomes between girls/liberals and boys/conservatives.

3.2 Personality Traits and Mental Health

Neuroticism

Of all personality traits, neuroticism may be the most theoretically relevant to both the extent and frequency of social-media engagement and its psychological effects. Characterized by heightened emotional sensitivity, individuals with high levels of neuroticism often experience disproportionately intense feelings of anxiety, sadness, and anger in response to even minor stressors.[46] Furthermore, neuroticism critically shapes coping strategies[47] and problem-solving behaviors;[48] those with elevated levels often resort to maladaptive approaches like avoidance—evident in behaviors like social-media procrastination or excessive rumination.

Justice Sensitivity

Neuroticism is also a significant predictor[49] of “justice sensitivity,” a nuanced trait marked by hypervigilance and acute negative emotional reactions to perceived injustices, whether directed at themselves (“victim sensitivity”) or at others (“observer sensitivity”). Individuals with high justice sensitivity have a lower threshold for detecting injustice, leading them to recall more (in)justice-related stimuli and to interpret ambiguous situations negatively.[50] They are prone to ruminate[51] over perceived injustices, experiencing and expressing more potent negative emotions in response to them.[52] Although these tendencies can inspire pro-social action, they can also carry mental-health risks, as regular vigilance for and negative emotional reactivity to exploitation and victimization may exact a psychological toll.[53]

Agreeableness

Justice sensitivity, which is closely related to neuroticism, parallels the trait of agreeableness, which can include the facet of compassion (e.g.,“I feel others’ emotions”).[54] This aspect of agreeableness prompts individuals to deeply resonate with the emotions and suffering of others, whether they are close associates or strangers, fostering pro-social behaviors and attitudes that align with the altruistic elements of justice sensitivity.[55]

However, as with justice sensitivity, when empathic concern exceeds certain bounds or is poorly regulated, it can exact a psychological toll. Individuals with heightened empathic abilities may experience intense interpersonal guilt, often fixating on their perceived shortcomings in relieving others’ pain or on their direct or indirect contribution to it.[56] Additionally, these individuals’ vulnerability to emotional contagion—the unconscious mirroring of others’ distress—can escalate to emotional overload and significant personal distress if not properly managed.[57] These dynamics—interpersonal guilt and maladaptive responses to emotional contagion—may help explain the demonstrated correlation between empathic concern and various internalizing symptoms such as depression,[58] especially among youth.[59]

Openness/Intellect

Openness/intellect, also known as “openness to experience,” is another broad personality trait with facets relevant to mental well-being. Broadly construed, it reflects a tendency to seek novel ideas, experiences, and stimuli. This trait encompasses two overlapping but distinct aspects: intellect, characterized by a keen interest in and engagement with abstract or semantic information; and openness, which signifies a strong affinity and receptiveness to sensory experiences and which includes facets like fantasy, emotionality, and aesthetic sensitivity.

Collectively, openness/intellect contributes to a variety of positive life outcomes, including cognitive flexibility, as well as academic and creative achievements. However, some of its facets may be double-edged with respect to mental well-being.[60] Specifically, the aesthetics facet, which involves an appreciation for and engagement with art and music, and the feelings facet, which is associated with greater emotional awareness and more intense emotional experiences,[61] are marked by heightened sensitivity to sensory stimuli.[62] This sensitivity amplifies experiences of both positive and negative emotions, which may explain the overlap between these facets and neuroticism. Perhaps due to this overlap, several studies have also linked these facets to internalizing disorders like depression.[63] Thus, in environments like social media, where negative stimuli often predominate, the psychological well-being of individuals with higher aesthetic and emotional openness may be more volatile and prone to deteriorating.

Conscientiousness

Conscientiousness, by contrast, is a broad personality trait that may reduce one’s psychological vulnerabilities. Marked by a propensity for organization, diligence, self-discipline, and goal-driven behavior, conscientiousness can serve as a buffer against mental-health problems. For instance, individuals high in conscientiousness often exhibit stronger self-efficacy[64]—the belief in one’s ability to achieve goals and navigate challenges—which can help protect against mental-health issues,[65] by making one less likely to feel overwhelmed and more likely to persist when facing adversity. Additionally, conscientious individuals exhibit stronger impulse control and are more likely to delay gratification,[66] which helps them to focus and block out distractions (e.g., social-media notifications). They also demonstrate more effective emotion regulation,[67] allowing them to recover more easily (i.e., return to a baseline or normal emotional state) after experiencing negative emotions.

Extroversion

Like conscientiousness, the broad personality trait of extroversion—encompassing facets of cheerfulness/enthusiasm, sociability, assertiveness, and excitement-seeking—has also been frequently linked with greater psychological well-being and life satisfaction.[68] This seems to be at least partly due to extroverts’ higher frequencies of social interaction and the greater quality of those interactions. Generally, more frequent social interaction increases social connectedness, protects against loneliness, and can lead to greater social support in times of need.[69] These effects may be further enhanced among those with higher levels of extroversion, who tend to derive greater enjoyment from social interactions.[70] More extroverted individuals are also more likely to partake in activities that conduce to better mental well-being, such as physical exercise and vacations.[71]

Interactive Effects of Personality Traits on Mental Health

While the traits highlighted above may independently influence mental well-being, a growing body of research indicates that these effects may also be interdependent, with their strength varying according to a person’s scores on other personality dimensions.[72] For example, the adverse impact of neuroticism on depression tends to be significantly more pronounced in individuals with low conscientiousness.[73] Indeed, there is growing evidence for a “worst two out of three” principle, in which individuals exhibiting high risk levels in any two traits and a low risk level in a third display similar internalizing symptom severity as those with high risk levels across all three traits. In particular, the protective effects of higher extroversion on depression are largely neutralized in individuals who also score high in neuroticism and low in conscientiousness.

These findings suggest that the cumulative effect of personality profiles within groups—such as between sexes or political orientations—could be a key factor in understanding their relative risks and experiences of mental-health issues.

3.3 Personality and Digital-Media Tendencies

In addition to their general relationship with mental health, many of these personality traits show distinct associations with digital-media tendencies. Although studies of facet-level relationships are elusive, domains like openness, neuroticism, and extroversion are all significantly positively correlated with the frequency of social-media use, though the underlying motivations vary.[74]

Individuals scoring higher in openness tend to seek out novel information, including intellectually stimulating, aesthetically pleasing, and emotionally engaging content. This leads to greater “information-seeking” behaviors on social media,[75] more consumption of digital news,[76] and more time spent searching for information in general.[77] Conversely, extroverted individuals often use social media for entertainment and to further social goals such as connecting with others, boosting social status, and garnering favorable attention.[78] This is reflected in their social-media-use patterns, which are marked by a higher frequency of updating profile statuses,[79] posting and commenting on messages and pictures,[80] and larger online (and offline) social networks.[81]

For those scoring high in neuroticism, frequent social-media use is more attributable to escapism, anxiety, insecurities with respect to real-life social interactions, and weaker impulse control. Research suggests that neurotic individuals turn to social media at least partly to distract themselves from or cope with offline pressures and responsibilities.[82] The relative anonymity of online platforms may also provide them a more comfortable environment for self-expression and interaction, which can be stressful in-person.[83] Combined with poor impulse control, these factors can intensify the urge for virtual “escapism,” which perhaps explains why neuroticism consistently emerges as the strongest personality predictor of social-media and smartphone addiction.[84]

In contrast, conscientiousness tends to be negatively correlated with general frequency of social-media use, perhaps because conscientious individuals tend to view social media as a distraction from other more important tasks.[85] Meta-analyses of existing studies generally show this relationship to be very modest[86] (if significant) or indistinguishable from chance.[87] Conscientiousness is, however, a significant negative predictor of addiction to social media and smartphones.[88] This aligns with the notion that individuals with higher conscientiousness, who possess better impulse control and self-discipline, can more easily delay gratification and disconnect from distractions like social media to prioritize more important tasks.[89]

3.4 Implications for the Social Media–Mental Health Relationship

Building on the theoretical mechanisms outlined earlier, there are multiple pathways through which social-media use can adversely affect those with “psychologically vulnerable” personality profiles. As noted, neuroticism, openness/intellect, and extroversion have all been previously linked to frequent social-media use, with neuroticism, in particular, associated with more addictive or problematic usage patterns. Individuals scoring high on these traits—particularly those who also display lower conscientiousness and neurotic tendencies—might find it challenging to detach from social media, which can detract time from sleep, exercise, and other mental health–promoting activities. Additionally, neurotic individuals are more likely to use social media as a means of escaping or avoiding immediate challenges or tasks. This behavior can lead to an accumulation of unaddressed tasks, potentially intensifying stress and anxiety.

Excessive social-media use also increases opportunities to engage in upward social comparisons as well as for being negatively evaluated or disparaged by others (e.g., cyberbullying). Individuals who rate high in neuroticism but low in conscientiousness and extroversion (particularly its assertiveness facet) are particularly vulnerable to these harms. Their heightened emotional sensitivity, lower self-confidence, and poorer emotional regulation are likely to increase their susceptibility to distress from upward comparisons and negative social feedback, as they are more prone to internalize and brood over feelings of inadequacy. For such users, social media may be a double-edged sword: although it offers a more comfortable environment for self-expression and communication, it simultaneously increases their exposure to social derogation and negative social comparison.

Social-media use can also provide more exposure to distressing news and “catastrophizing” media narratives, which can be particularly triggering for those higher in neuroticism, the compassion-related facets of agreeableness, and emotional or aesthetic openness. These traits are closely linked with “justice sensitivity,” which predisposes individuals to be perceptually vigilant toward perceived injustices and inequalities and to react to them with stronger negative emotion.[90] Habitual engagement with content pertaining to injustice, which is prevalent on social media, could, over time, lead to cumulative psychological strain for justice-sensitive individuals.

The interplay between personality traits and social-media tendencies is reflected in data from Pew’s American Trends Panel (ATP), which show that the frequency of observing social-media content that elicits negative/internalizing vs. positive emotions varies as a function of scores on the Big 5 personality domains.[91] These relationships are visualized in Figure 16, which plots the independent effects of a standard-deviation increase in each personality domain (measured in 2014) on two indexes that capture the average frequency (measured in 2018) at which panelists reported seeing social-media content that makes them feel different negative/internalizing (depressed, lonely) and positive (inspired, connected, amused) emotions, respectively.

First, consistent with its tendency toward experiencing and expressing positive affect, extroversion positively predicts the frequency of encountering content that evokes positive emotions. However, this relationship is significant only after adjusting for controls. In contrast, the relationship between extroversion and the frequency of encountering content that elicits negative or internalizing emotions is weaker and remains statistically insignificant in both the baseline and covariate-adjusted models.

Second—as theory would expect, given its inherent negativity bias—the opposite pattern is observed for neuroticism, which is significantly more strongly associated with the frequency of encountering content that induces negative/internalizing emotions than positive ones.

Openness, on the other hand, significantly predicts both frequencies, which is to be expected, since individuals higher in this trait tend to experience stronger emotions across the board. Similarly, but in the opposite direction, conscientiousness significantly and negatively predicts the frequency of encountering social-media content that triggers both negative and positive affect, though its relationship with the former is slightly stronger. This may be because those with higher conscientiousness tend to have stronger emotional regulation or suppression,[93] which moderates the experience and expression of emotion in general. Finally, agreeableness is positively associated with the frequency of both emotional outcomes, though these relationships are comparatively small in magnitude and are no longer statistically significant when adjusting for demographic/ socioeconomic covariates.

Figure 17 expands these relationships, showing that the frequency of exposure to content that triggers negative or positive emotions is predictive of longer-term mental-health outcomes. Specifically, the higher the average frequency at which panelists reported (c. 2018)[94] encountering social-media content that made them feel “depressed” and “lonely,” the more frequently they reported experiencing internalizing symptoms at each of the four time points in 2020–22. Conversely, but to a smaller extent, higher average frequencies of positive emotions correspond to significantly lower frequencies of internalizing symptoms. These positive and negative relationships persist and remain significant not only when controlling for demographic/socioeconomic covariates from both[95] waves of the social-media emotions and internalizing symptoms measurements (gray markers), but also when adjusting for past scores on the internalizing symptoms index (red markers).

But what do the relationships depicted in Figures 16 and 17 mean? The panel data on which they are based did not measure predictor and outcome variables concurrently, so we do not know the panelists’ mental-health state at the time when their responses to social-media content were recorded. Thus, it is not possible to draw causal inferences from these relationships.

However, there are at least several plausible, nonexclusive interpretations for these patterns. One is selective exposure, where individuals high in neuroticism and low in conscientiousness or those with greater internalizing symptoms—may actively seek out or pay more attention to distressing social-media content.[97] This pattern of “doomscrolling”—habitual excessive consumption of negative news on social media—has been linked with poorer mental health, higher levels of neuroticism, and lower levels of conscientiousness.[98]

An alternative, or additional, explanation is that mental-health conditions and associated personality dimensions may shape how individuals process and emotionally react to social-media stimuli. For instance, a news item that might evoke, at most, a mild emotional response from persons who are more conscientious and less neurotic could provoke a stronger reaction among their more neurotic and less conscientious counterparts.

Crucially, both selective exposure and emotional responsiveness may also be influenced by moral-ideological orientations, which are, in turn, linked to the personality facets previously discussed. For example, facets of justice sensitivity, certain aspects of neuroticism like “withdrawal,” the “openness” aspect of openness/intellect, and the compassion facet of agreeableness are all positively related—and facets of conscientiousness negatively related—to egalitarian/anti-hierarchy ideological orientations.[99] Ideological egalitarians tend to be more sensitive to social inequality and more likely to attribute poverty and group disparities to systemic forces like discrimination.[100] As a result, they are more prone to attend to and be emotionally affected by portrayals of inequality on social media, which may amplify distress and feelings of helplessness, ultimately undermining mental health.

3.5 Implications for Sex and Ideological Differences in Mental Health

The preceding discussion indicates that social media’s net psychological effects are not uniform but vary according to users’ personality profiles. For individuals with traits associated with psychological resilience and stability—specifically, low neuroticism, emotional/aesthetic openness, justice sensitivity, and empathic concern, and high conscientiousness and extroversion—the net effects of social media might be negligible or even beneficial. Conversely, for those with the opposite profile—high neuroticism, emotional/aesthetic openness, justice sensitivity, and emphatic concern, and low on conscientiousness and extroversion—the psychological impact is likely to be larger and more negative on balance.[101]

The moderating effect of psychological profile may help explain why the findings on social media’s psychological effects have been mixed. Specifically, the heterogeneity in the effects of social media depending on psychological traits is likely to be obscured when effects are examined in the aggregate. Larger negative effects for some users will be offset by the positive and null effects for others, thereby producing an overall effect size that, while negative, is not far from zero.

The role of psychological profiles also offers insight into the relatively poorer mental-health outcomes of girls and liberals in the digital age. Girls, for instance, tend to score significantly higher than boys on personality facets associated with internalizing disorders—a pattern illustrated in Figure 18, which uses data from one of the largest U.S. adult personality data sets.

Notably, women score significantly higher than men on neuroticism (particularly on its “anxiety” and “vulnerability” facets), which are the most potent personality predictors of internalizing disorders and excessive social-media use. Additionally, women score higher on traits like emotional and aesthetic openness and compassion, each of which are linked, to varying to extents, both to mental-health challenges generally and to frequency of engagement with and emotional responses to negative social-media content.

Conversely, women score lower on assertiveness, a facet of extroversion related to self-confidence and self-esteem. Although women do register higher on certain facets of conscientiousness—which is broadly linked to psychological resilience and stability—these differences tend to be more modest. Moreover—given the “worst two out of three” principle discussed in Section 3.2—the protective benefits of these facets may not be enough to outweigh the psychological vulnerabilities posed by women’s higher scores on the other risk factors.

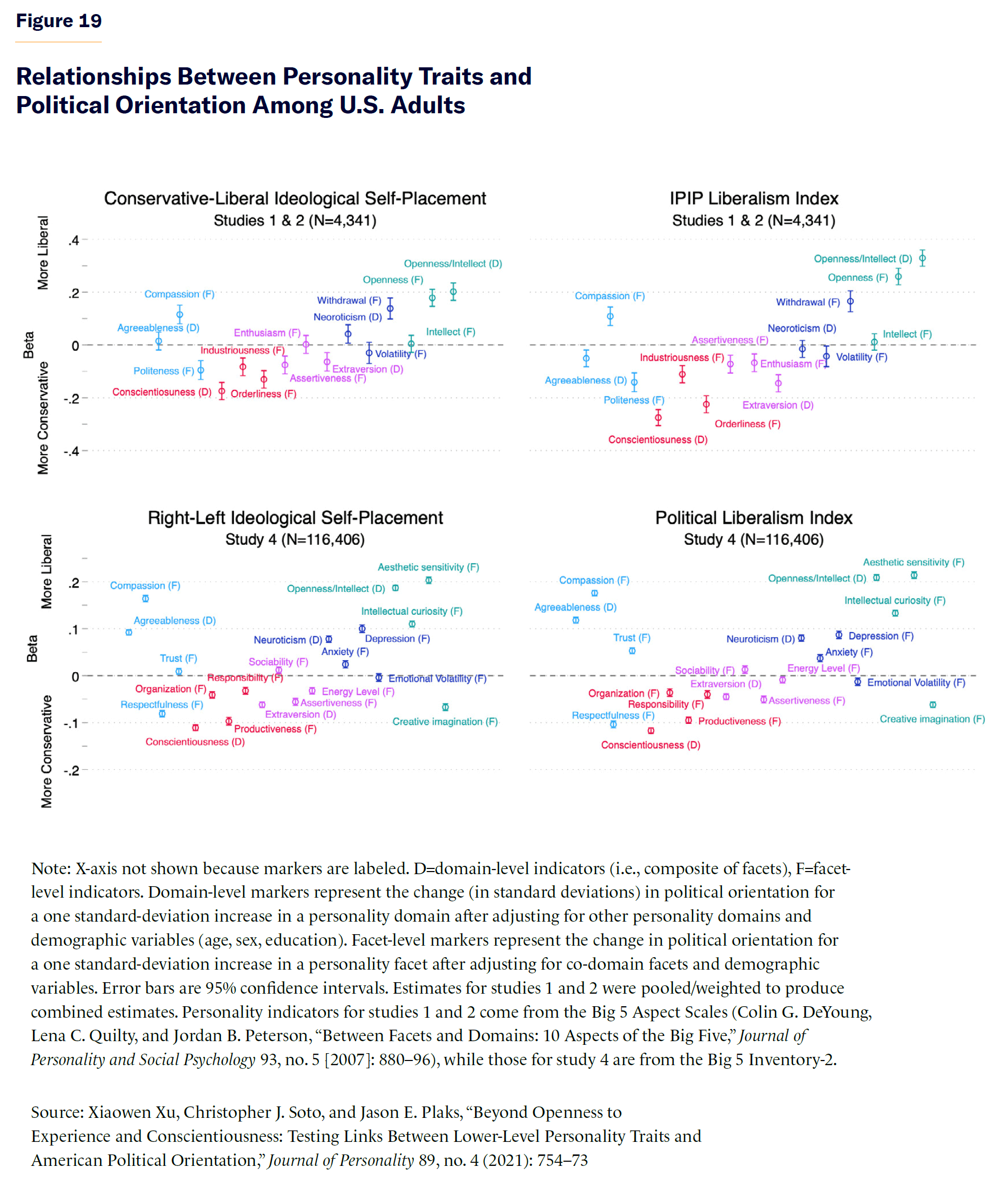

Importantly, as depicted in Figure 19 below—sourced from three large and recent studies of U.S. adults—some of the same personality facets that distinguish girls from boys similarly distinguish liberals from conservatives. Similar to the pattern observed in sex differences, we see that the “withdrawal” aspect of neuroticism (encompassing the “depression” and “anxiety” facets), the “openness” aspect of openness/intellect (encompassing “aesthetic sensitivity” and “emotionality”), and the compassion aspect of agreeableness (encompassing facets like tender-mindedness and empathic concern) are all positively linked with liberal/left-wing political orientations. Conversely, facets of conscientiousness and certain facets of extroversion, such as assertiveness, are associated with conservative/right-wing political orientations.

Because girls and liberals tend to score higher than boys and conservatives on key facets of neuroticism, openness, and agreeableness—all of which are positively associated with justice sensitivity—it follows that girls and liberals would also likely score higher on justice sensitivity. Data presented in Figure 20, drawn from three separate studies of U.S. adults, supports this expectation. Across studies, on most, if not all four, aspects of justice sensitivity (observer, beneficiary, perpetrator, victim), women score significantly higher than men and liberals significantly higher than conservatives. The bottom row of Figure 20 additionally shows that these ideological differences hold within each sex, with female liberals outscoring female conservatives, and male liberals outscoring than male conservatives.

Taken together, these data show that girls and liberals tend to score significantly higher than boys and conservatives on personality traits associated with mental-health challenges, and significantly lower on those associated with psychological resilience and stability. In other words, some of the same traits that help explain the poorer mental-health outcomes of girls relative to boys may also be relevant to explaining the poorer mental-health outcomes of liberals relative to conservatives. In fact, this vulnerability in girls may be tied, at least in part, to their disproportionate alignment with liberal/left-wing ideological orientations.

There are several ways in which these differences may help explain not only sex and ideological differences in mental health but also differences in the effects that social media may have on these groups’ mental well-being.

The first possible cause of these relationships is general digital connectivity. Recall that previous research has linked higher neuroticism and lower conscientiousness to excessive internet and social-media use; and higher openness/intellect to more frequent internet and social-media use, as well as digital news consumption. These findings are important, as those who spend more time on social media and on the internet in general will naturally have more opportunities to be psychologically affected by digital content and less time to engage in offline activities beneficial to mental well-being. Given the scores of liberals on these traits, it’s reasonable to anticipate that liberals exhibit greater digital connectivity than conservatives.

This expectation aligns with the data presented in Figure 21, which shows that, across both sexes, young adult and 12th-grade liberals, respectively, are significantly more likely to report using the internet “almost constantly” (top panel) and spending more than 20 hours a week on leisure internet activities (bottom panel) than their conservative counterparts. These differences persist when controlling for education, household income, and other demographic/background variables. In the online Appendix, I further show that these patterns are also evident in continuous measures of internet use, such as the number of hours spent online each week.

More moderate but similar patterns are observed for social-media connectivity, shown in Figure 22. Overall, referring to the first row of charts, 12th-grade and young adult (18–21) liberals are consistently about 10 points more likely to be frequent social-media users (at or above the 75th percentile on measures of daily or weekly social-media hours). These patterns—which hold for the U.S. population generally (second row of charts)—also appear to be qualified by sex, such that liberal and conservative females tend to report using social media more frequently than their male counterparts. In general, social-media use tends to be highest among liberal females and lowest among conservative males, though exceptions to the former pattern are evident in some measures/data sets.

Figure 23 further reveals that young adult liberals of both sexes consistently report using a larger number of social-media apps than their conservative counterparts. This suggests that liberals are exposed to a greater variety of social-media formats, content, and experiences than conservatives. For instance, in addition to other platforms such as Twitter, Reddit, and Tumblr, young liberals—especially young female liberals—are significantly more likely to use TikTok, an app increasingly at the center of public concerns about the social media–mental health relationship.[102]

Differences in the frequency of digital- and social-media connectivity could thus contribute to the relatively greater deterioration of girls’ and liberals’ mental health in the social-media age. At the same time, it’s important not to overstate the magnitude of the difference in frequencies of social-media use, which tend to be small to moderate.

Differences in emotional responses to social-media content and interactions—as well as in attention to certain kinds of content—may be equally, if not more, relevant to understanding the sex and ideological gaps in mental health. First, higher average levels of neuroticism, empathic concern, and justice sensitivity among girls and liberals would likely make them much more sensitive to negative social evaluations (aesthetic, moral, intellectual, etc.) when interacting with others on social media. While this proposition cannot be tested directly, Figure 24 presents suggestive evidence, drawn from the MTF survey of 12th-graders. Specifically, girls, irrespective of political orientation, and liberals, regardless of sex, report significantly higher levels of concern about how they are perceived by others. Interestingly, during 2017–22, the share reporting this concern has grown by 13–17 points among liberal 12th-graders of both sexes and by 12 points among conservative females. In stark contrast, no net change is observed among conservative males who, as we’ve seen, tend to fare comparatively better on indicators of mental health and report the lowest rates of frequent social-media use.

Second, due to higher levels of neuroticism, emotional and aesthetic openness, empathic concern, and justice sensitivity, we might expect women and liberals to be more emotionally affected by negative or depressing (as well as positive) social-media content. Alternatively, or in addition, women and liberals may be more likely to seek out or attend to such content when it circulates.

Recall that neuroticism, openness, and agreeableness were all positively predictive—and conscientiousness negatively predictive—of the reported frequency of encountering social-media content that triggers feelings of depression and loneliness. Given these relationships and the sex and ideological differences in these personality traits, we would expect women and liberals to report encountering such content at significantly higher frequencies than men and conservatives. Data graphed in Figure 25 confirm that they do, with women scoring approximately 0.24 of a standard deviation higher than men, and liberals scoring just under 0.4 of a standard deviation higher than conservatives. Crucially, domain-level neuroticism (N) and agreeableness (A)—measured four years earlier, in 2014—account for nearly half the difference between women and men, which, for context, is larger than the share explained by all socioeconomic/demographic indicators combined. Sex differences in domain-level openness and conscientiousness tend to be much smaller (with the latter even favoring women), so it is unsurprising that they account for none of the difference in the frequency of encountering social-media content that provokes negative internalizing emotions. In contrast, domain-level neuroticism (N), agreeableness (A), openness (O), and conscientiousness (C) together explain roughly a third of the difference between liberals and conservatives, which, again, is larger than the share explained by all socioeconomic/demographic indicators combined. Individually, conscientiousness and neuroticism have the largest moderating influence, followed by openness and agreeableness. In the final model, these four personality domains and the battery of socioeconomic/demographic indicators together explain more than half the liberal–conservative difference in exposure to social-media content that triggers internalizing emotions, rendering this difference no longer statistically significant at the conventional p < 0.05 threshold.

If girls and liberals are more sensitive to negative social evaluations, and if they are more likely to have stronger emotional reactions to and/or attend to negative social-media content, it follows that frequent social-media use will be relatively more psychologically consequential for them than for boys and conservatives. Unfortunately, existing publicly available data do not permit an adequate or a complete test of this hypothesis. Data do, however, provide some general support for it.

The data in Figure 26—although restricted to sex differences and encompassing overall digital screen time rather than exclusive social-media use—show that the bivariate relationships between daily screen-time hours and negative mental-health outcomes have generally become stronger over time for high school girls, compared with boys. The most pronounced growth has been in the relationship between screen time and reporting a major depressive episode (i.e., feeling sad or hopeless almost every day for two weeks or longer). This relationship was near zero in 2003 and has been increasing ever since, particularly from 2011 onward, coinciding with the rise of smartphones and social media. In contrast, the effect for boys has seen minimal change overall.

While no time-series data are available, a similar hypothesis can be tested using cross-sectional data from the 2018 AARP Brain Health and Mental Well-Being survey. Figure 27 illustrates the average score differences on a seven-item anxiety index and a 20-item depression index between self-identified liberals and conservatives. These individuals reported using social media for over two hours at a time at least several times a week (36% of the sample), compared with those who rarely do (46% of the sample). Among liberals, those who use social media more frequently score 0.33 standard deviations (SD) higher on the anxiety index and 0.22 SD higher on the depression index, compared with those who report never using social media for over two hours at a time minimal use. In contrast, these differences among conservatives are negligible, at 0.05 and 0.04 SDs, respectively.

Although it uses different, and arguably more ambiguous, measures of social-media-use frequency, the 2022 wave of the American National Election Studies’ 2020–22 social-media study (Figure 28) reveals similar results. Among liberals, average depression scores increase with greater social-media use. For example, those who reported daily use of at least one platform (70% of liberals, 64% of conservatives) score significantly higher on a two-item depression index, compared with those who never use social media (7% of liberals, 8% of conservatives).

Conservatives show much smaller and less consistent increases in depression across usage levels. Specifically, while liberals who reported daily usage scored 0.34 SD higher in depression than those who do not use any social media, the difference for conservatives is close to zero and not statistically significant.[103]

These findings suggest that even if girls and liberals and boys and conservatives were to spend similar, if not equal, amounts of time on social media, the former two groups would be worse off in terms of mental well-being. Among these groups, liberals—especially liberal females—may suffer the most. Not only are liberals higher in neuroticism, emotional and aesthetic openness, empathic concern, and justice sensitivity—traits they share with women—but they also tend to score lower in conscientiousness, which likely puts them at a disadvantage in terms of emotional regulation and focus. This further heightens their susceptibility to negative rumination and doomscrolling. In fact, the very limited data that we have on the intersection of ideology and doomscrolling—from a small study of an online sample of 500 of residents in OECD countries[104]—indicate that liberal and left-aligned individuals score significantly higher (just under 0.3 SD) on measures of doomscrolling, compared with those on the political right.[105]

As liberals and conservatives likely have different social-media experiences—gravitating toward different apps, attending to different kinds of content, and having differing emotional responses to even the same content—it follows that the same level or frequency of social-media engagement has differential effects on their mental health.

However, people’s social-media experiences—particularly the content they encounter—are at least partially influenced by the broader media and political context. As Figure 29 illustrates, using the salience of terms in the New York Times, since about 2011, news-media attention to societal issues like “racism,”“inequality,”“discrimination,” and “sexism” has surged to unprecedented levels.[106] Concurrently, the underlying sentiment reflected in news headlines has become decidedly more negative[107] and pessimistic.[108] Of course, some of this is attributable to the rise of Trump and his presidency, which served to intensify these trends and, consequently, the alarm felt by many liberals.

Naturally, given the increasing interplay between social media and mainstream news media, these trends are also apparent in—and, at least in some instances, likely influenced by—social-media discourse. To illustrate, Figure 30 plots time series of the frequency at which various social-justice-related terms are featured in tweets on Twitter (now known as “X”), an app disproportionately frequented by liberals. As shown, until roughly 2014–15, the frequencies of most terms were generally close to zero before surging in the period thereafter. Although all have leveled off or declined since 2020—much like increases in psychological distress—they generally remain well above the rates of the earlier pre-“Great Awokening” era.

As the tenor and content of media coverage have become more negative and alarmist, so have the perceptions of sociopolitical issues among young liberal females and males. As shown in Figure 31, young liberals—especially liberal females—have become much more socially and politically conscious over the past 10 years.[109] For instance, the share of liberals who say that they frequently think about the “social problems of the nation and the world” has reached record highs, as has the share who say that working to “correct social and economic inequalities” is “extremely” important for them. Concerns about race relations and the environment have also surged, while changing remarkably little among conservatives of both sexes.

Despite the significant educational and socioeconomic advancements that women have achieved since the 1950s, Figure 32 further shows that liberals now perceive greater discrimination against women in various contexts (including in accessing higher education) than ever recorded. Concurrently, the share of female liberals who think that their sex will prevent them from obtaining their desired careers “somewhat” or “a lot” shot up by more than 30 points between 2012 (36%) and 2019 (67%). In contrast, if they’ve changed at all, perceptions of discrimination against women are lower among conservatives of both sexes today than they were in the late 1970s.