Improving U.S. Immigration: Employment-Based Visas Should Attract the World’s Best, Not Repel Them

The U.S. immigration system’s reliance on random lotteries, arcane standards, and excessive paperwork leads to perverse outcomes that do not advance the national interest. It is possible to improve this system, especially for highly skilled immigrants seeking employment-based visas, without adding to the number of people admitted or changing the criteria by which potential immigrants are eligible for particular visas.

The U.S. takes far longer to process most employment and skills-based immigration applications than other wealthy English-speaking nations;[1] this is mainly a consequence of the Department of Labor’s excessive involvement in the immigration process. Long wait times for permanent U.S. residency based on employment push many aspiring immigrants and employers into temporary work visas. These long processing times, as well as restrictions on visa holders’ family members (who are authorized to live in the U.S. but not authorized to work or establish businesses), make current visa programs in the U.S. unattractive for many high-skilled immigrants.

The main policy recommendations of this report include:

- For H-1B temporary worker visas, United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) should implement a wage ranking rule, based purely on the age and location of the visa recipient, in order to assign limited visas. This would reduce uncertainty in the selection process, select more young and more highly paid migrants, and stop employers from cheating the system.

- Congress should reform the H-1B visa cap to set aside an allotment for new firms requesting a visa. This would level the playing field with large businesses and contracting firms.

- Congress should extend AC21 treatment to L-1 visa holders in order to reduce the artificial demand for H-1B visas.

- DOL should exempt the most highly paid immigrants in the EB-2 and EB-3 immigrant visa categories from PERM and PWD regulations, which slow processing times by more than a year.

- Congress and USCIS should expand work-authorization eligibility to international students and most work-visa dependents. These immigrants are already legally admitted to the U.S. but are currently unable to work. Reforming work eligibility would make U.S. visas more attractive to high-skilled immigrants and their families.

Introduction

"We lead the world because, unique among nations, we draw our people—our strength—from every country and every corner of the world.

Thanks to each wave of new arrivals to this land of opportunity, we’re a nation forever young, forever bursting with energy and new ideas, and always on the cutting edge, always leading the world to the next frontier. This quality is vital to our future as a nation. If we ever closed the door to new Americans, our leadership in the world would soon be lost."—Ronald Reagan, January 19, 1989[2]

President Ronald Reagan was right in stating that immigrants are a key reason that the U.S. is at the cutting edge of technology and innovation. He was also correct that if the U.S. closes the door to immigrants, our leadership in the world would soon be lost. The unfortunate reality is that while the country has not formally closed its doors, over time it has built a system of bureaucratic locks that are increasingly difficult to unlock, even for most high-skilled immigrants.

One of the objectives of a good immigration system should be attracting and retaining highly skilled individuals to the shores of the United States. Unfortunately, the U.S. is falling short of this goal. The U.S. assimilates newcomers well, relative to other nations, and, as economists Ran Abramitzky and Leah Boustan describe in their new book Streets of Gold, the “children of immigrants from nearly every country in the world are more upwardly mobile than the children of US-born residents who were raised in families with a similar income level.”[3] However, the U.S. admits few immigrants and nonimmigrant workers based on their skills (i.e., their potential for economic productivity and success) relative to similar English-speaking developed nations, both as a share of the overall population and as a share of all the noncitizens admitted.[4] As a consequence, a lower share of noncitizens in the U.S. have a college degree than in many other countries with advanced economies.[5]

An area of immigration policy where Americans should find consensus is wait times. There should be a timely process to admit whatever number of immigrants is legally permissible each year. Furthermore, U.S. policy should give priority and quicker paths of admission to immigrants with the greatest potential to contribute to the nation’s economy. This is critical at a time when allied nations are competing for the world’s top talent to innovate in new fields and create new technologies. As remote work becomes more common, the clock is ticking to bring the most talented and highest-paid people of the world to the U.S., where they can contribute to our local and national economies and pay taxes, rather than stay in cheaper locations abroad.

We can and should make existing visa programs more attractive, without changing which or how many immigrants are eligible for permanent residency or a limited number of work visas. This would allow us to select more highly skilled immigrants to come to the U.S., to the benefit of American citizens and the noncitizen residents already here.

Important Definitions and Acronyms

The U.S. immigration system includes a complicated assortment of visas that vary depending on country of origin, employment status, education status, skills, wealth, family associations in the U.S., intended length of stay, and actual length of stay. Table 1 lists the key terms and forms that are discussed in the rest of this report.

Table 1

| USCIS | United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS)—a branch of the Department of Homeland Security—oversees lawful immigration to the United States. USCIS determines eligibility for immigration benefits such as visas and naturalization but does not issue visas; visas are issued by the Department of State. |

| CBP | Customs and Border Enforcement (CBP) guards the borders of the United States. CBP staffs legal ports of entry, where it can legally admit immigrants or parole them. |

| Immigrant vs. nonimmigrant visas |

Immigrant visas are those that allow the individual who holds one to enter the U.S. and stay permanently. After an immigrant visa holder settles in the U.S., he receives a permanent residency card, commonly called a “green card,” which the immigrant can then use to travel. Nonimmigrant visas are all other visas—including tourist, student, or work visas—that allow someone to come to the U.S. temporarily. |

| Immigrant intent | Immigrant intent means that the immigrant intends to stay permanently in the United States. All immigrant visas require immigrant intent. |

| Nonimmigrant intent | Nonimmigrant intent means that the visitor intends to eventually leave the U.S. after the terms of his legal stay end. Most nonimmigrant visas require nonimmigrant intent at the time of the grant of the visa. Intent can change after the visa holder is in the U.S., although the process can be complicated. |

| Dual intent | Dual-intent visas can be granted to those who intend to stay and those who intend to return. Nonimmigrant visas such as the H-1B and L-1 are dual-intent. |

| I-90 | Form filed with USCIS by green-card holders to replace lost green cards or to renew if they haven’t naturalized. Immigrants with green cards must renew them every 10 years. |

| I-129F | Form filed with USCIS by a U.S. citizen to sponsor a noncitizen spouse for permanent residency. |

| I-130 | Form filed with USCIS by U.S. citizens and some green-card holders who want to sponsor their relatives to live permanently in the United States. These could be the parents or children of U.S. citizens or the children and spouses of green-card holders. |

| I-140 | Form filed with USCIS by U.S. companies or some immigrants to determine whether they are eligible for employment or skills-based permanent residency. |

| I-485 | Form filed with USCIS by those with an approved I-129F, I-130, or I-140 who are already in the U.S. to receive a green card without going abroad to a U.S. consulate to obtain an immigrant visa. This process is called “adjustment of status.” |

| Consular processing | The process of obtaining an immigrant visa for those outside the United States. For those not already in the U.S., consular processing is the only way to seek permanent residency. Those inside the U.S. can seek permanent residency by filing form I-485. |

| I-539 | Form filed with USCIS by those in the U.S. on a nonimmigrant visa to change to another type of nonimmigrant visa. |

| I-526 | Form filed with USCIS by those who make large investments and create a certain number of jobs in order to apply for permanent residency. |

| I-751 | Form filed with USCIS by immigrants to remove the conditions on permanent residency; often used by immigrants who are the spouses of U.S. citizens after they are married for at least two years. |

| I-765 | Form filed with USCIS by noncitizens seeking a work permit. |

| I-829 | Form filed with USCIS by immigrant investors already in the U.S. with green cards to remove the conditions on their permanent residency and verify that their investment is still viable two years later. |

| I-924 | Form filed with USCIS by regional investment centers seeking designation for the first time so that EB-5 investors can pool their capital in these investment opportunities. |

| I-924A | Form filed with USCIS by regional investment centers seeking annual certification to maintain status. |

| N-400 | Form filed with USCIS by immigrants with permanent residency to obtain citizenship. |

| EB-1 | Immigrant visa for those with extraordinary ability and global recognition. Immigrants or their employers file an I-140 to obtain an EB-1. |

| EB-2 | Immigrant visa for those with exceptional ability and advanced degrees. Employers file an I-140 to sponsor an EB-2 for an immigrant. |

| EB-2 NIW | An EB-2 visa with a National Interest Waiver (NIW), which removes the need for an employer sponsor to file an I-140. |

| EB-3 | Immigrant visa for skilled and non-college-educated workers. Employers file an I-140 to sponsor an EB-3 for an immigrant. |

| EB-4 | Special catch-all category of immigrant visa for various types of immigrants, including allies of the U.S. military abroad and religious workers. |

| EB-5 | Immigrant visa for millionaire investors who create jobs in the United States. |

| Regional investment centers | A more streamlined path to obtain an EB-5, through investment in a government-approved regional investment center, rather than direct investment. |

| TEA | Designated high-unemployment or rural areas where the investment threshold for the EB-5 visa program is reduced to $800,000. |

| B-1/B-2 visas | Nonimmigrant visas granted to short-term visitors to the U.S. for tourism or business purposes. They do not allow holders to work. |

| E-2 visa | Nonimmigrant visa granted to investors (and their families) from countries with treaties with the United States. |

| E-3 visa | Nonimmigrant work visa reserved for Australian citizens who come to work at a specialized occupation. It is similar to the H-1B visa but requires nonimmigrant intent. It was created as part of a free-trade agreement with Australia. |

| F-1 visa | The main nonimmigrant student visa for international college students. It requires nonimmigrant intent. While it is not a work visa, it allows international students to work on campus and elsewhere under certain conditions. |

| CPT | The F-1 visa Curricular Practical Training Program allows F-1 visa holders to work full-time for up to one year, or part-time indefinitely, in order to do internships and other work required as part of their course work. |

| OPT | The F-1 visa Optional Practical Training program allows F-1 visa holders to work one year during their program or after graduation in jobs related to the field of study. It does not require employer sponsorship. |

| STEM OPT | STEM OPT is a two-year extension of the OPT program for F-1 graduates in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math fields. |

| F-2 visa | Nonimmigrant dependent visa for the minor children and spouses of F-1 students. Like the principal visa, it requires nonimmigrant intent. |

| H-1B visa | Nonimmigrant work visa for immigrants in specialized fields that require a college degree or greater experience and employer sponsorship. It is a dual-intent visa. |

| H-1B1 visa | Nonimmigrant work visa similar to the H-1B visa but with reserved spots for Chilean and Singaporean citizens created as part of free-trade agreements with both nations. However, unlike the H-1B visa, it requires nonimmigrant intent. |

| H-2A visa | Nonimmigrant work visa for seasonal agricultural workers in selected fields. It requires nonimmigrant intent. |

| H-2B visa | Nonimmigrant work visa for seasonal non-agricultural workers in selected fields. It requires nonimmigrant intent. |

| H-4 visa | Nonimmigrant dependent visa for the spouses and minor children of H-1B, H-2A, and H-2B visa holders. It is a dual-intent visa for the dependents of H-1B visa holders; and nonimmigrant for dependents of H-2A and H-2B visa holders. |

| J-1 visa | Nonimmigrant exchange visa for researchers, professors, and participants in medical training and cultural programs. It requires nonimmigrant intent and, in some cases, requires the immigrant to spend a number of years in his home country before returning, after the visa expires. |

| J-2 visa | Nonimmigrant dependent visa for the spouses and minor children of J-1 visa holders. |

| L-1 visa | Nonimmigrant work visa for the workers of multinational companies in specialized fields to come to the United States. It is a dual-intent visa. |

| L-2 visa | Nonimmigrant dependent visa for the spouses and minor children of L-1 visa holders. |

| O-1 visa | Nonimmigrant work visa for individuals with extraordinary ability in their fields. It requires nonimmigrant intent. |

| TN visa | Nonimmigrant work visa, created as part of the North American Free Trade zAU*7SZCXAgreement, for citizens of Mexico and Canada in certain professions that require a minimum education or experience. It requires nonimmigrant intent. |

| TD visa | Nonimmigrant dependent visa for the spouses and minor children of TN visa holders. |

| Incident to status | This term is used to refer to benefits or rights that aliens in a specific legal status are entitled to without the need to apply for them, such as work authorization for certain statuses. |

| TPS | Temporary Protected Status is a legal status granted by the president of the United States or the Secretary of Homeland Security to all the citizens of a designated country that is experiencing conditions that make it unsafe for the citizens of that country to return safely—such as a natural disaster, war, disease, or a humanitarian crisis. TPS is available to aliens regardless of whether they enter legally or illegally, or whether they hold another legal status at the time. TPS allows migrants to work for any employer and protects them from deportation. Designations last up to 18 months and must be extended by the executive to continue. |

| DED | Deferred Enforced Departure is a presidentially granted protection from deportation that may also authorize immigrants to work; it is similar to TPS but is not a legal status. |

| Refugee | Under U.S. law, a refugee is someone who is outside the U.S. and “is unable or unwilling to return” to his country of nationality “because of persecution or a well-founded fear of persecution on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion.” The president determines how many refugees to admit and from which parts of the world. |

| Asylum seeker | An asylum seeker is someone who meets the definition of a refugee but is already present in U.S. territory. There is no limit to the number of asylum seekers admitted, since they are already present in U.S. territory. Unlike refugees, they are not immediately authorized to work and must apply for authorization. |

| DACA | Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals is a program created by the Obama administration that protects a number of immigrants who entered the U.S. unlawfully before June 2007 before they turned 16 years old, meet certain educational characteristics, and have not committed serious crimes. They can obtain work authorization. |

| EAD | An Employment Authorization Document is usually a card issued by USCIS that proves that an immigrant has work authorization in the United States. |

| I-94 | An electronic record of arrival and departure issued at legal ports of entry by CBP agents to those legally admitted into the U.S. for a period. |

| PERM | The Program Electronic Review Management is the process and system developed by the Department of Labor to certify that employers seeking to hire immigrants permanently—i.e., sponsor them for a green card—have complied with all laws regarding prioritizing U.S. nationals for the job and paying so-called prevailing wages. |

Source: “Definition of an I-94,” U.S. Customs and Border Protection, Dec. 21, 2021; “Working in the United States,” USCIS; “Forms,” USCIS; “Directory of Visa Categories,” U.S. Dept. of State

Today’s Temporary Paths for High- Skilled Nonimmigrants

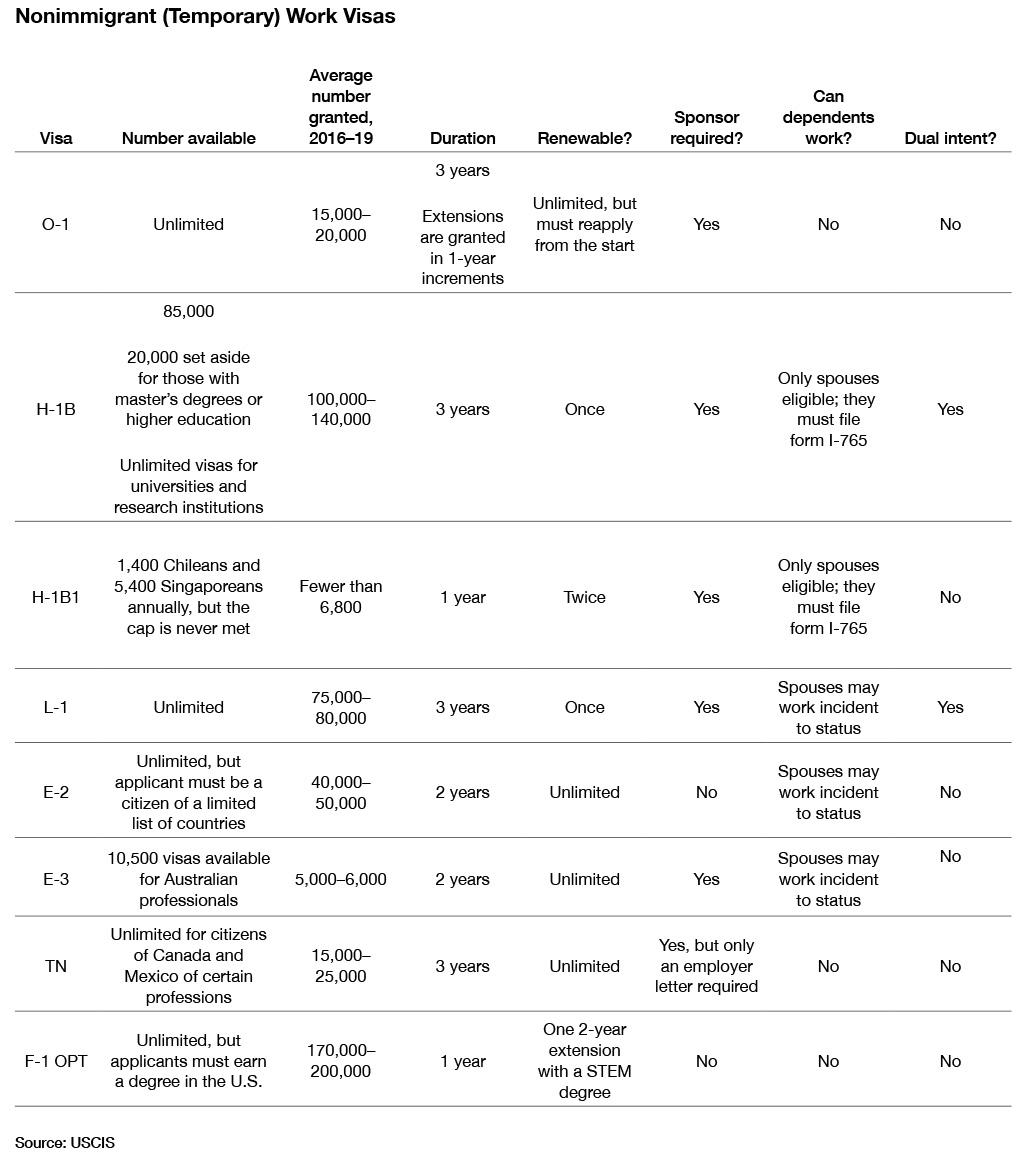

High-skilled nonimmigrants and investors who wish to come to work temporarily in the U.S. usually need a company to sponsor them; the nonimmigrants will work exclusively for that company after they arrive. But the process to start working can take well over a year, unless nonimmigrants are lucky to be from a few specific countries and have certain professional skills. Table 2 lists the visas available for businesses to legally hire nonimmigrants who are not already eligible through some other legal status that allows them to work.

Table 2

The options in Table 2 may give the false impression that the process to sponsor a high-skilled nonimmigrant is simple and that there are many paths. In reality, the application process is unnecessarily long, costly, and riddled with nonsensical legal requirements.

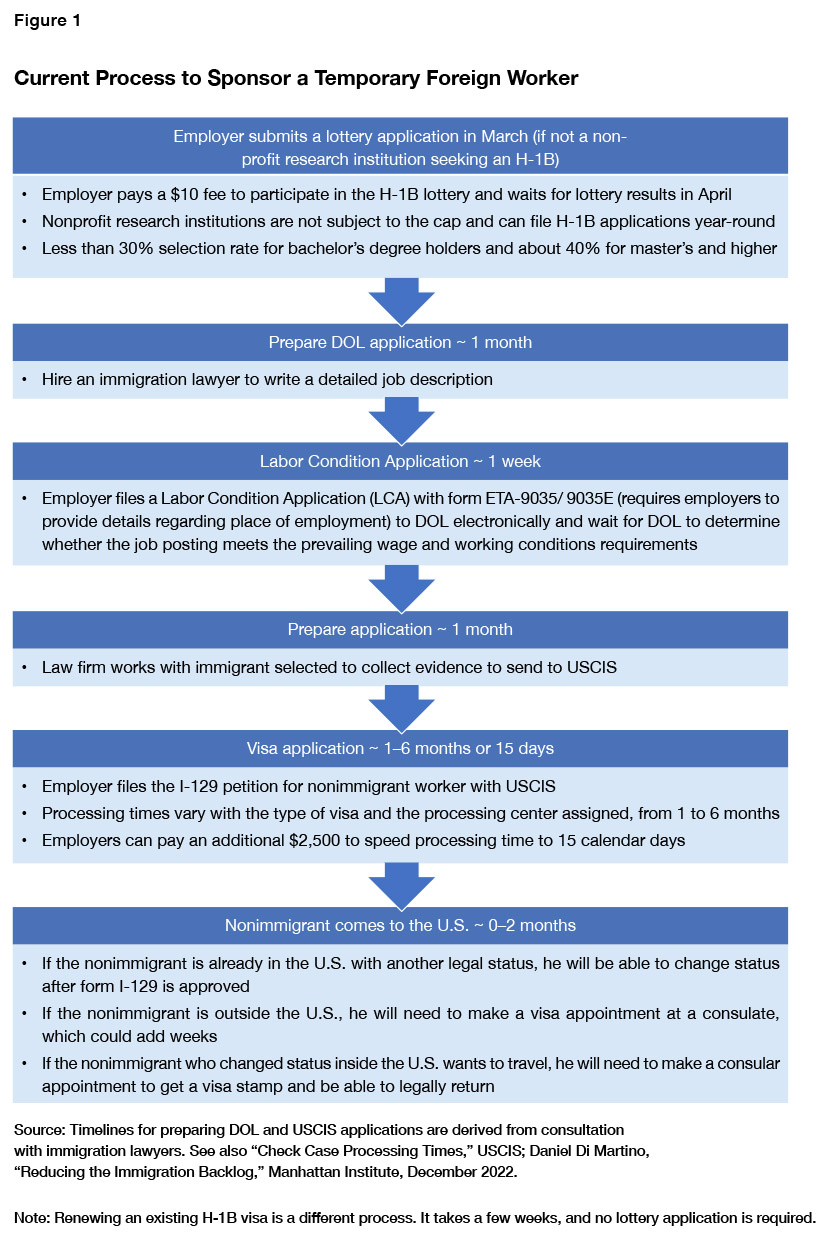

For example, sponsoring a typical H-1B worker, the largest temporary high-skilled work visa category (Figure 1): the process takes weeks or months for each applicant (USCIS processing can take as long as seven months), even if the applicant pays premium processing fees to speed it up and is already in the U.S. under another visa.[6] Additionally, the process not only involves immigration authorities but also the Department of Labor (DOL). In total, the process can cost an estimated $10,000 per nonimmigrant employee[7] and at least six months in processing time, barring any audit, request for further evidence, or obstacle that emerges, delaying the process by months and increasing its cost.

In addition, employers seeking to sponsor an H-1B visa must enter a lottery for a limited 85,000 spots in March of every year—not any other time—and the migrant can begin working only at the beginning of the fiscal year, October 1.[8] The lack of flexibility and long processing times dissuade companies, especially small ones, from ever sponsoring a high-skilled nonimmigrant. This is why most H-1B visas are captured by the largest technology corporations, which apply for more slots than they need, anticipating a low selection rate. This process also dissuades many high-skilled nonimmigrants from even trying to come to the U.S. when they have better options in other developed economies with faster processes, such as the United Kingdom.[9]

Some nonimmigrants do not need an employer to sponsor them to come to work in the U.S.; they can apply on their own if they obtain the applicable visas, but those visas require the aspiring nonimmigrant to be either an investor with substantial capital in an active, physical business in the U.S., or an international student who obtained an undergraduate or graduate degree in the U.S. right before beginning to work.

Today’s Permanent Paths for High- Skilled Immigrants

If a high-skilled immigrant wants to come to the U.S. permanently, the pathways are even narrower. This process is what is commonly called applying for a “green card,” though the real term is “immigrant visa.” After such a visa is obtained and the immigrant is in the U.S., he or she becomes a legal permanent resident and will receive a permanent resident card, commonly known as a “green card.”

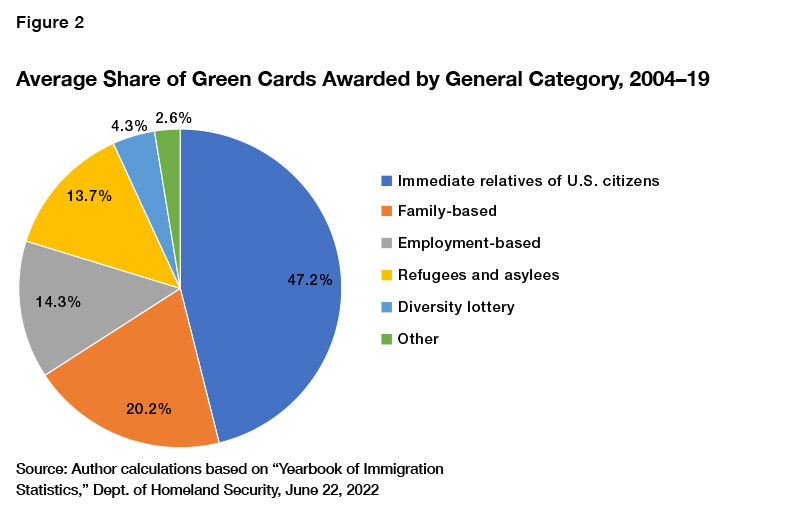

There are five main categories of immigrant visas:[10]

1. Immediate relatives of U.S. citizens (unlimited admission): minor children, spouses, and parents

2. Family-based (up to 226,000 annually): siblings of U.S. citizens, adult children of U.S. citizens and green-card holders, and spouses of green-card holders

3. Employment-based (up to 140,000 annually): skills-based and employer-sponsored immigrants and their immediate relatives

4. Refugee or asylee (refugee cap set by the president and asylees; unlimited)

5. Diversity (up to 55,000 annually): a lottery for immigrants only from countries with historically low rates of immigration to the United States

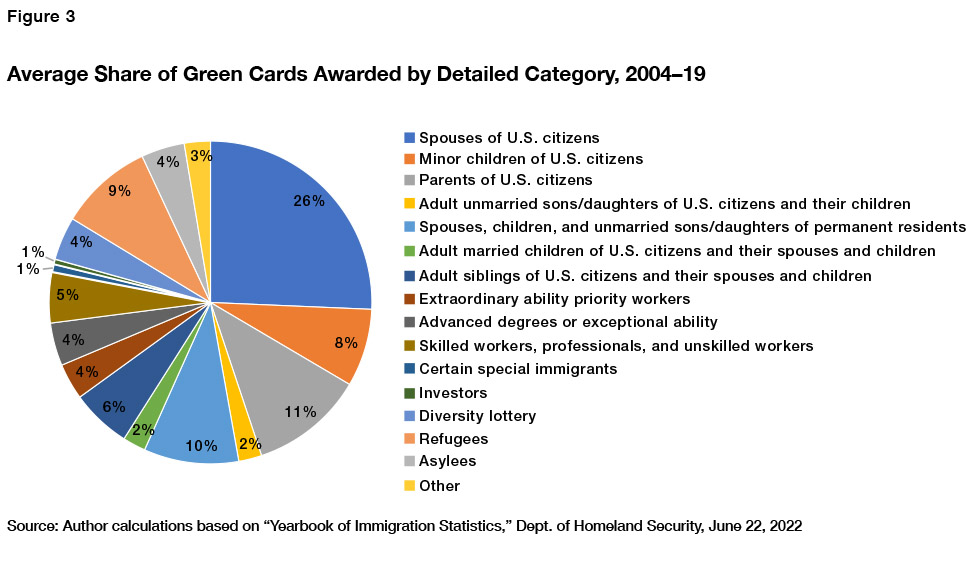

For at least the last decade, about 1 million immigrants have obtained permanent residency each year—excepting 2020 and 2021, when personal and policy responses to the Covid-19 pandemic halted immigration.[11] Variations in legal permanent resident flows happen mainly through the refugee or asylee channel and the immediate relative of U.S. citizens channel, while the family-based, employment-based, and diversity channels are maxed out every year to their congressionally established caps. Figures 2 and 3 illustrate the proportion of green cards awarded by category.

Employment-Based Visas and Permanent Residency

If a high-skilled immigrant or investor does not have an immediate relative who is a U.S. citizen, or is already in the U.S. through another of the categories above, he or she must apply for an Employment-Based (EB) visa. EB visas comprise five subcategories:[12]

1. EB-1 Priority workers: This immigrant visa is the most difficult to obtain. If the immigrant can prove extraordinary ability in his field through compelling evidence, he can self-petition or self-sponsor without an employer. The other way to obtain an EB-1 is by being an outstanding college professor with international recognition, or a multinational manager or executive sponsored by employers. This visa does not require input from DOL and is capped at about 40,000 immigrants annually, inclusive of their immediate family members.

2. EB-2 Professionals with advanced degrees or persons of exceptional ability: This visa can be obtained by employers for immigrants with advanced degrees, or those who can show exceptional ability, which is a similar concept to EB-1 workers but with less strict criteria. This visa does require undergoing the labor certification process (in which an employer must demonstrate an ability to pay prevailing wages to the visa applicant), but the immigrant can avoid working through an employer and self-petition if he obtains a National Interest Waiver (NIW). These waivers require the applicant to demonstrate that the activity that the immigrant will pursue in the U.S. is of national scope and furthers the national interest and that the applicant is well-positioned to advance the activity. The visa is capped at about 40,000 immigrants annually, inclusive of their immediate family members.

3. EB-3 Skilled workers, professionals, and unskilled laborers: This visa is for individuals with at least two years of relevant working experience in their profession—those with college degrees in the occupation that they are entering, as well as unskilled workers for jobs that do not require training. There is always a labor certification requirement for EB-3, and it is also capped at about 40,000 immigrants annually, inclusive of their immediate family members.

4. EB-4 Certain special immigrants: The EB-4 is not necessarily a skills-based visa but a catchall category for religious workers such as immigrant priests, juveniles abandoned by their parents, some international organization employees, and even Afghan and Iraqi translators or interpreters. The visa is capped at about 10,000 immigrants annually, inclusive of their immediate family members.

5. EB-5 Investors: Immigrants can obtain this visa by investing at least $1.05 million in a new enterprise and creating at least 10 jobs for U.S. workers. Some applicants can invest a lesser amount ($800,000) if they do so in a targeted employment area, i.e., areas of the U.S. with high unemployment. Investors can also pool their capital into government-authorized regional investment centers. The visa is capped at about 10,000 immigrants annually, inclusive of their immediate family members.

Out of the approximate 1 million legal permanent residents awarded a green card annually, just 140,000 are awarded permanent status because they have a job offer in the U.S. and have extraordinary or exceptional skills, or because they are investing large sums of capital and creating employment opportunities for others.[13] This number includes the spouses and dependents of the immigrants admitted; thus, the number of skills-based immigrants admitted to the U.S.—a country of more than 330 million people—was fewer than 60,000 individuals in 2019,[14] or less than 0.02% of the population.

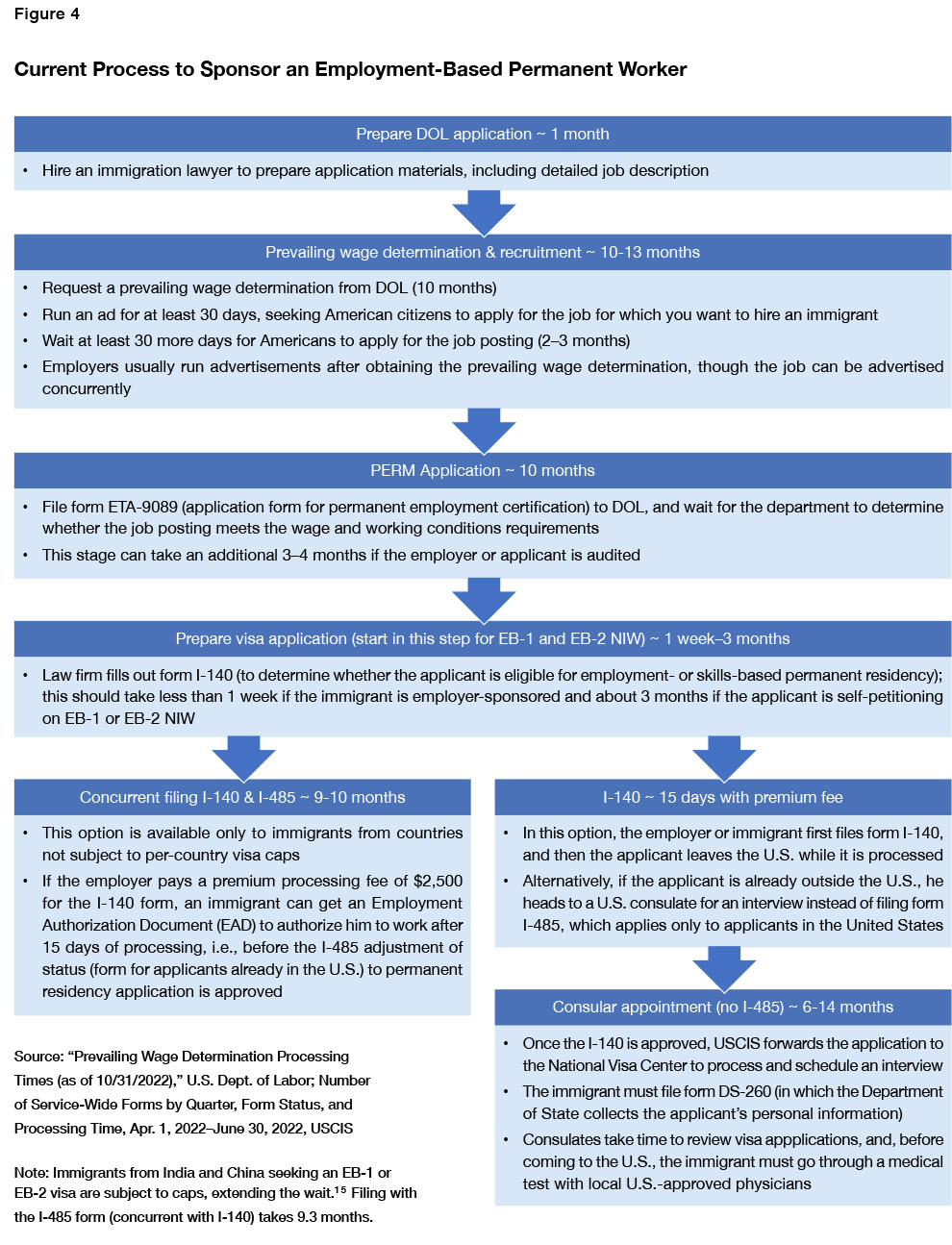

The process for sponsoring this small number of permanent residents is even more arduous than for temporary workers, which is why most employment-based permanent residents are sponsored for temporary work visas first; employers then begin the process of applying for permanent residence after they are already working in the United States. The process (Figure 4) usually takes about two years but can be done in as little as nine months for some categories but as many as four and a half years for others. This applies to all immigrants except those born in India and China, where case per-country caps on visas apply and many applicants might never obtain permanent residency. A primary reason that the application process time for permanent residents takes longer is the different labor certification process (commonly known as PERM) and the Prevailing Wage Determination (PWD) request, each of which takes about 10 months longer than for temporary work visas today.

Temporary Work Visas

The H-1B visa program is the nation’s largest temporary employment visa program. Immigration restrictionists as well as labor groups oppose the program, claiming that employers use this visa to avoid hiring more costly U.S. workers. The evidence points to the contrary: H-1B visa holders are well paid and often work in the technology or computer science sectors; about half hold master’s degrees or higher, and they innovate and make their coworkers more productive.[16] Moreover, the U.S. admits relatively few H-1B visa holders, considering the size of our population. Just 85,000 H-1B visas are allowed, under the law, for all businesses—except for research and educational institutions, which are exempt from this cap.[17]

Because more applications are submitted than there are available visas, USCIS conducts two lotteries of entries and allows those selected to apply: first, for the 65,000 spots for every cap-subject petition; and then, for the 20,000 spots remaining for applicants with advanced degrees. This gives an estimated selection rate of less than 30% for an applicant with an advanced degree.[18]

However, two issues lead companies to apply for more H-1B visas than they need. First, the excessively long timeline for obtaining permanent residency makes the H-1B visa the only viable option to sponsor migrants and have them working in the U.S. promptly (in as little as three months). The visa will expire after six years, giving employers the opportunity to begin sponsoring the aspiring immigrants for permanent residency. If businesses that sought permanent immigrants, not temporary ones, had access to EB immigrant visas in a timely manner, they would not apply to sponsor H-1B visas. Second, the random nature of the H-1B lottery leads many large firms to sponsor more migrants than they need, with the goal of gaming the lottery. If a technology firm, for instance, needs 100 H-1B noncitizen workers and estimates that the H-1B lottery selection rate will be 25%, it will sponsor 400, knowing that only 100 will be selected. The top 10 H-1B sponsoring companies obtained nearly 12% of all H-1B visas in fiscal year 2019; Amazon and Google were the top recipients.[19] The lottery also fuels third-party employment firms—companies dedicated almost exclusively to requesting H-1B visas and then placing those workers in other firms.

Reforming the H-1B Visa Program

There are simple ways to reform H-1B visas to solve these issues. First, cap-subject H-1B visas should be allocated based on a straightforward age and geographic wage formula, not luck or the prevailing wage system. Under the current prevailing wage system, employers must pay H-1B workers a wage that is no less than that for similarly qualified workers for the same job in the same geographic area where the noncitizen is employed. The current system uses occupation descriptions and experience ranges to determine the prevailing wage. This system is flawed because DOL staff makes a subjective judgment over which government-listed occupation most closely resembles the job description of the H-1B application, leading businesses to game the system by describing the occupation to reduce the prevailing wage required.

The wage formula proposed by this paper—the age and geographic wage formula—cannot be manipulated by employers because it will adjust for characteristics not controlled by the sponsoring business or migrant (age of the visa holder) or for characteristics that are difficult to change (the location of the job). The age and geographic wage formula would assign H-1B slots based on percentiles within the distribution of wages paid to U.S. workers by age group in the metropolitan area of each H-1B petition. Here is what that means: if one visa is available and one 30-year-old applicant and one 40-year-old applicant have the same wage offer in the same city, the younger candidate will win the visa because younger employees, on average, earn less than older employees, putting the 30-year-old in a higher wage percentile ranking. If two applicants of the same age have the same wage offer, but one applicant is in a low-income area and the other applicant is in a high-income area, the applicant residing in the low-income area will win the visa because the same wage offer puts him in a higher wage percentile ranking for his geographic area.

Allocating cap-subject H-1B visas by age and area-adjusted wage percentiles reduces selection uncertainty for all applicants over time and makes the strategy of over-submitting in the H-1B visa lottery unprofitable for large companies. Finally, using age and location deflators for the wage allocations allows the visa system to favor highly paid noncitizen workers at the beginning of their careers in low-cost areas, assuring that not all visas will go to larger cities or older workers who have fewer years to contribute in taxes to the system.

Second, Congress should set aside 20,000 H-1B visas for new firms, rather than for migrants with advanced degrees. If visas are allocated by an age and geographic wage formula, it is not necessary to give preference to noncitizens with higher education but who are earning lower wages. Noncitizens with PhDs in social science and who earn an average salary, for instance, should not be awarded a visa over an applicant with a bachelor’s degree in an emerging sector with an above-average salary offer. New firms do not have the time or resources to game the visa system, and they usually seek a specific person for a particular role—that person just happens to be a noncitizen. This is especially important for start-ups and the technology sector, which are critical for innovation and economic growth.

Under this new system, Labor Condition Applications (LCAs) will take less time to complete, and USCIS can twice conduct a wage allocation selection: first, for the 20,000 slots for new firms; and a second round of selection for the 65,000 slots for all applicants. This would guarantee that at least 23.5% of new H-1B visas are allocated to new and emerging firms.[20]

Third: we have excessive and unnecessary H-1B visa applications submitted due to bureaucratic rules that force businesses into this visa program when they prefer to use other visas. As stated above, the lengthy permanent residency process encourages businesses to apply for an H-1B visa although they actually want to sponsor a worker for a green card. But many H-1B applications are submitted for noncitizens who were previously on L-1 visas and are seeking an intracompany transfer: in fiscal year 2021, 6% of all approved H-1B applications came from noncitizens and their spouses and children previously on L-1 visas.[21]

L-1 visa holders, unlike H-1B visa holders, do not qualify for a provision of the law commonly known as the “AC21 rule,” from the American Competitiveness in the 21st Century Act.[22] The AC21 rule allows aspiring immigrants who hold an H-1B visa and have an approved I-140 petition or a pending I-485 adjustment of status to continue renewing their H-1B beyond the six-year maximum.[23] This means that many L-1 visa holders apply for H-1B visas and then file for permanent residency, especially visa holders from India, who, due to caps on the number of green cards per country of origin, must wait for decades for a green card with an approved I-140. A commonsense solution to avoid an excessive number of H-1B applications is for Congress to extend the AC21 rule to L-1 visa holders.

A New Path for Temporary Foreign Workers

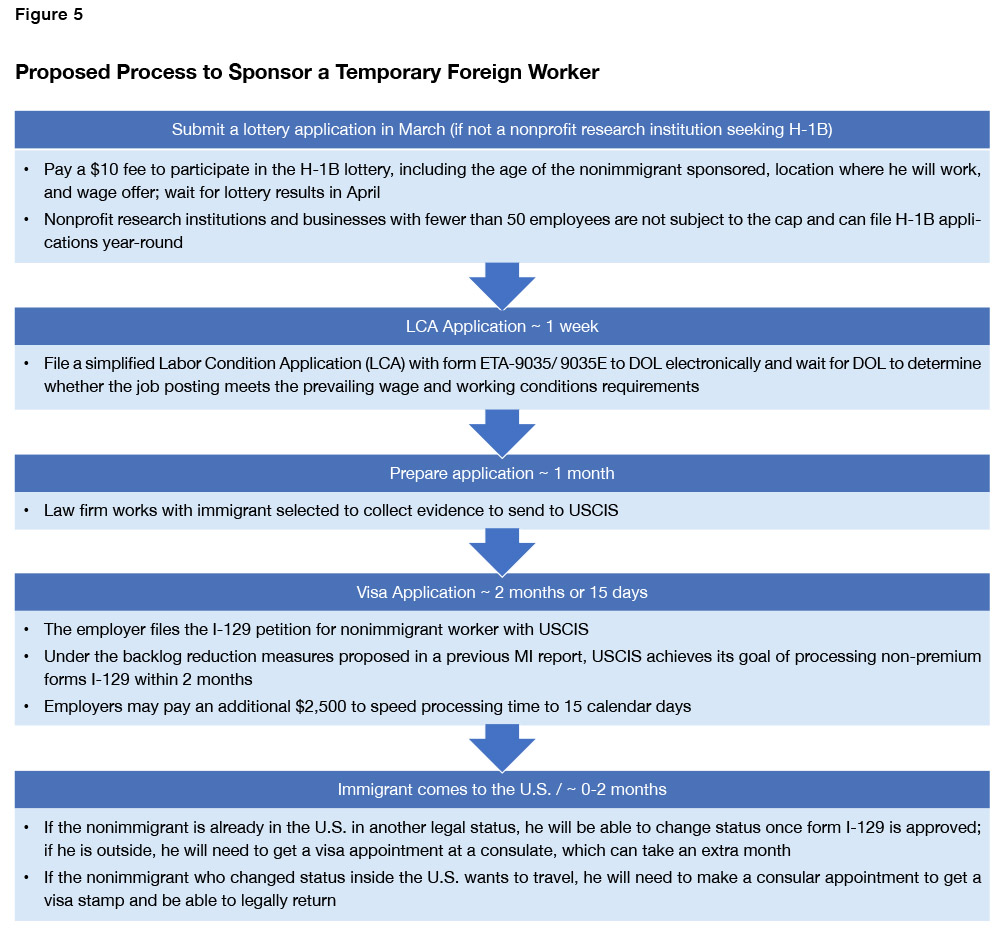

There is a better way for the U.S. to process visa applications for nonimmigrant (temporary) workers. Under the proposal illustrated in Figure 5, four months would be the standard processing time—or two months, with premium processing. The total cost would be an estimated $7,000–$10,000 per employee.

Maximizing the Contributions of High-Skilled Immigrant

A significant obstacle to attracting high-skilled migrants on nonimmigrant (temporary) visas in the U.S. is that their dependents cannot work. We have admitted hundreds of thousands of high-skilled nonimmigrants in the past decade but excluded their spouses and children from fully participating in the economy, creating an underclass in plain sight. The foreign-born children of a nonimmigrant college professor who attend high school in the U.S. cannot even seek a summer job; nor can the spouses (often highly skilled, too) seek productive employment outside the home. And if that same professor had a child born in the U.S., that citizen sibling would have more rights than the other. But that new U.S. citizen child does not provide any immigration benefit to the family until he or she turns 21 and is able to sponsor them, if needed.

Forgetting the Family

How can the U.S. attract the top talent of the world on an O-1 extraordinary ability visa if their spouses and children aren’t allowed to work while they live in the U.S., potentially for decades? The same is true for the H-4 spouses of H-1B visa holders who can work only after the H-1B visa holder has an approved I-140 petition, while their children cannot work at all. The TD spouses and children of Canadian and Mexican TN visa holders cannot work even with an approved I-140. International students on F-1 visas are allowed to work on campus but not for outside employers, in most circumstances, inhibiting innovation and entrepreneurship. If an F-1 visa holder is a married PhD student with children, his or her family cannot work while they live in the U.S. and complete a degree—that could mean about seven years for a PhD program. This prohibition is not a reasonable expectation for visa holders. It hurts nonimmigrant as well as American families for the nation to miss out on the contributions of individuals who tend to be just as skilled as their spouses.

Restrictions on F-2, H-4, O-3, and TD visa dependents stand out against the more liberal regime for J-2, L-2 and E-2 visa dependents. This latter group can work: upon requesting authorization, in the case of J-2; and immediately upon arrival, in the case of L-2 and E-2 visa holders.

Congress—and USCIS, to the extent that executive authority permits—should allow nonimmigrant visa dependents on F-2, H-4, and O-3 visas to work incident to status and exempt J-2 visa holders from requesting work authorization and also allow them to work incident to status, just as L-2 and E-2 visa holders are allowed.

This proposed expansion of work-authorization eligibility to new visa categories can be done seamlessly without a bureaucratic hassle, just as it is done today for E-2 and L-2 visa dependents. After the nonimmigrant enters through a legal port of entry, the border agent issues an I-94 electronic record with the category E-2S or L-2S, which is evidence of work authorization. In the case of the newly eligible categories, this would be O-3S, H-4S, and F-2S. (This treatment should also be extended to J-2 visa holders, as recommended in the earlier report on reducing immigration backlogs).[25]

Student Visa Work Authorization

Additionally, F-1 student visa work authorization should be expanded.[26] Currently, international students can work freely only for their university and only part-time during the academic year. Universities are allowed to grant curricular practical training (CPT) to students enrolled in courses that require internships and count toward their degree, but this is too limited for students who might wish to start their own businesses or work within their area without enrolling in an internship course. Instead, if possible, the Department of Homeland Security should reinterpret the CPT program to allow students to work part-time off-campus in an enterprise or a business that they create directly related to their field of study after receiving authorization from school officials, just as they do with CPT. If a regulatory change is not possible, Congress should amend the Immigration and Nationality Act[27] to expand F-1 work authorization, as well as granting work authorization to the dependent visa categories listed in Table 3.

Table 3

Who Benefits from Work Authorization

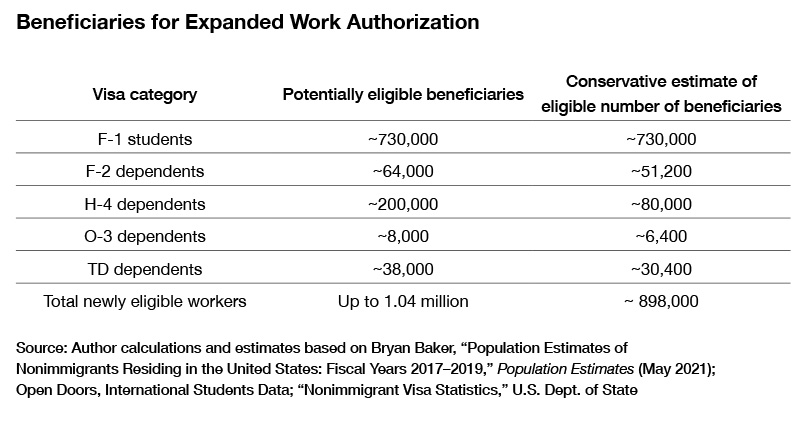

The number of nonimmigrants who would benefit from this expansion in work eligibility is substantial, totaling about 1 million legal nonimmigrants in the United States.

F-1 students: To obtain the number of enrolled F-1 students, I use data from Open Doors[28], a project of the Department of State, and exclude: (a) nondegree track students who would not be eligible for work authorization; and (b) Optional Practical Training (OPT) program holders who already have work authorization.

F-2 dependents: I first examined Department of State data on issuances of F-1 and F-2 visas since 2017[29] and found that over 93% of these visas issued were F-1 visas, and less than 7% were F-2. I assume that this same share would hold for the resident F visa population, including those on OPT but not those on nondegree programs, which would not be eligible for work authorization, as reported in Open Doors.[30] This implies that there are nearly 64,000 F-2 dependents in the U.S. who could potentially benefit. However, this number of possible beneficiaries, like all other dependent numbers, is overstated because some of these dependents are young children.

H-4 dependents, O-3 dependents, and TD dependents: I use estimates of the size of the nonimmigrant visa-holding population from the Department of Homeland Security[31] and the same visa issuance data (previously mentioned) from the Department of State in order to reach the other estimates of potential beneficiaries. DHS does not distinguish dependents from the principals, so I used Department of State statistics on the number of visas issued by category for the last five years to estimate the share of all temporary workers who are dependents, and then estimated the share of the dependent population by visa type.[32] The great uncertainty in this estimate is that Canadians do not need a visa issued by the Department of State to work on a TN visa in the U.S.; they can obtain it directly at any legal port of entry. Therefore, we do not know how many Canadians receive TN status every year or how many dependents; we know only the number of Mexicans who receive this status. For the purposes of this report, I assume that more Canadians than Mexicans use this visa program. This assumption is based on the larger share of college-educated Canadians and the lower cost of entry to obtain the visa, despite the much larger population of Mexico.

These more conservative estimates take the 306,000 potential beneficiaries from expanded dependent work authorization and shed beneficiaries who are necessarily ineligible. While some of these 306,000 potential beneficiaries are minor children, most are likely spouses who are, in fact, eligible. A further complication is that some of the H-4 spouses are spouses of H-2A and H-2B visa holders (making them ineligible for this expansion of work authorization), or are already work-authorized because their H-1B spouse has an approved I-140. To yield a conservative estimate of the potential number of beneficiaries, I assume that 75% of the dependent population are spouses while the rest are dependent children and that half the H-4 population is already work-authorized or ineligible. Then I assume that only 20% of the child-dependent population could actually work if authorized, since dependents can be up to 20 years old. This leaves us with an estimate of nearly 165,000 dependents who would be eligible for work authorization, in addition to the F-1 students who could now work off-campus under an expanded CPT program and the easier work-authorization process for hundreds of thousands of work-eligible J-2 and H-4 visa holders.

Granting work authorization to high-skilled visa dependents is crucial to attracting highly skilled migrants to the United States. Potential nonimmigrants choose which country to go to based partly on the opportunities available to their families, and highly educated individuals are more likely to be married than those with less education.[33] When visa dependents are able to work legally in the U.S., they will be able to more fully participate in society. Furthermore, expanding the CPT program for F-1 students can potentially attract more international students to our shores at a time when U.S. school enrollment is declining.[34] This would allow university towns to thrive with newcomers who purchase goods and services locally.

By increasing the value of moving to the U.S., without changing eligibility rules for any of these visas, we can increase both the number and average level of skill, talent, and potential earnings of nonimmigrants interested in temporary work or research. Granting work authorization to these visa holders would also allow nearly 1 million people who already live in the U.S. to enter the labor force and work, create businesses, pay more in taxes, and contribute to the economy, benefiting everyone in the process.

Accelerating the Employment-Based Permanent Residency Process

The primary problem with permanent employment-based immigration is the time that it takes to process applications. Accelerating processing times with expanded premium processing and reduced use of form I-765, as proposed in the preceding report,[35] will help, but it won’t be enough. Even if the previously proposed measures were to be implemented, the typical EB-2 advanced-degree green-card applicant will go from waiting about 30 months to waiting 20 months if he pays the premium processing fee for form I-485. That is still too long.

Out of the approximately 30-month timeline for an EB-2 applicant, about 20 months, or two-thirds of the total, is spent dealing with DOL.[36] Unlike H-1B applications, EB visa applications require a PWD before employers can file. And, instead of an LCA, EB visa applications require a PERM application. Unfortunately, DOL takes approximately 10 months[37] for each of these steps.

As Figure 4 above illustrated, the first step is to ask DOL for the wage that the employer should be paying the immigrant based on his occupation, location, and experience. This central planning allows the government to decide how much immigrants are paid and allows employers to game the system by how they describe the roles. The second step is the recruitment process. For green-card petitions, employers must attempt to recruit U.S. workers before hiring permanent immigrants, a process that the government requires to be two months but that most employers do concurrently with the PWD to save time. If any American applies for the job, he must be given priority consideration and be interviewed. If the American is not hired, the employer must explain why. After these two steps, the employer submits form ET-9089—the PERM step—which asks DOL to verify that the employer performed the previous two steps. DOL is allowed to audit or request more evidence from the employer.

This process is supposed to protect U.S. workers from fewer than 40,000 new permanent residents every year who are sponsored workers under EB-2 and EB-3 (fewer than 40,000 because family members of EB-2 and EB-3 immigrants count toward the approximate 80,000 cap and receive most of the slots).[38] EB-1 is exempted from this process because of its high eligibility threshold.

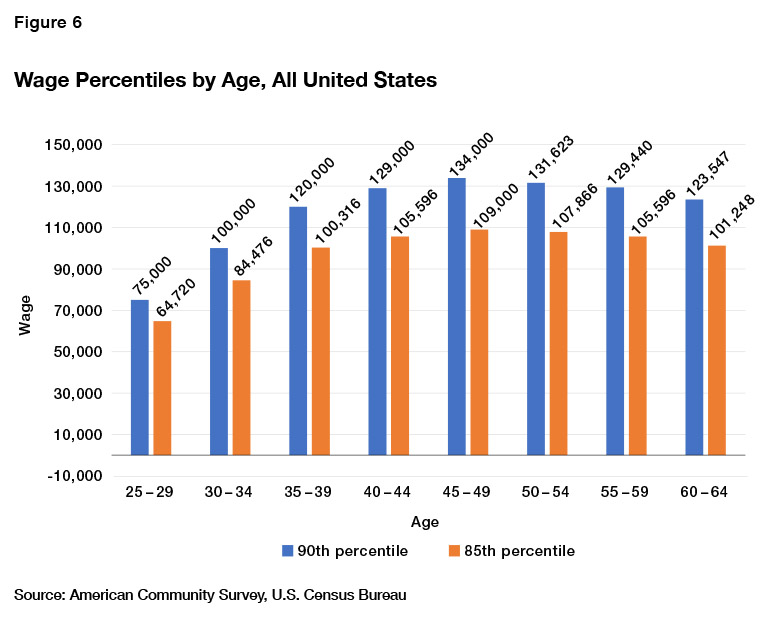

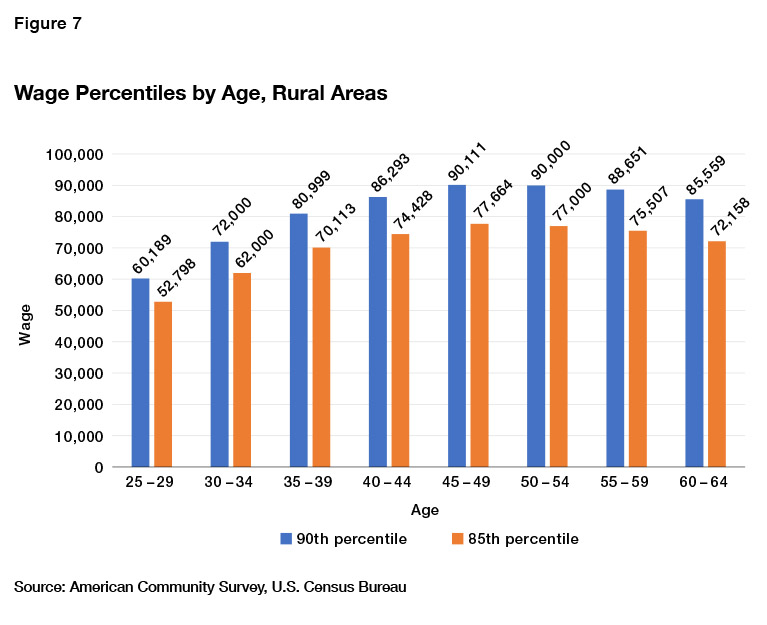

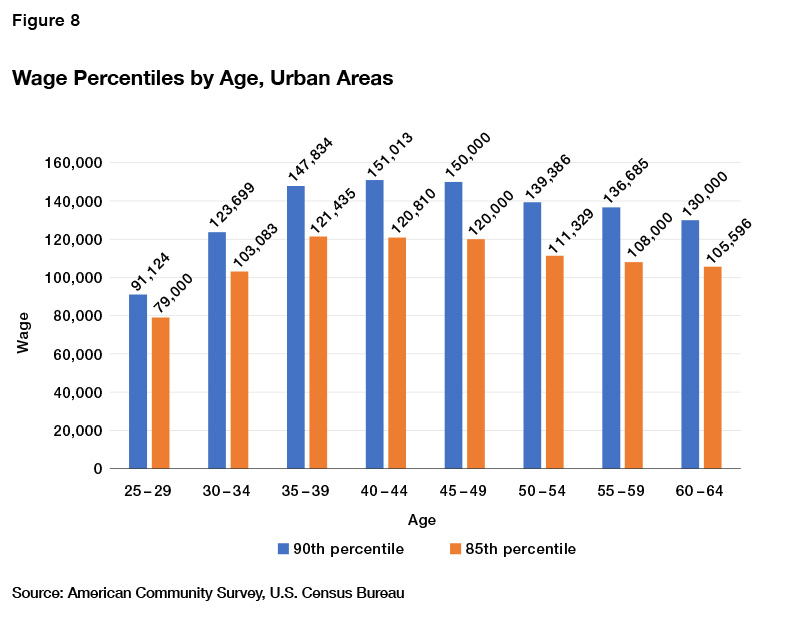

Proposed Reform: Use Age and Location

To protect U.S. workers and accelerate processing, DOL should exempt EB-2 and EB-3 visa applicants who meet a high wage floor from the PWD and PERM process. This way, the most highly paid immigrants receive the visas promptly. Specifically, EB-2 visa applicants whose wage offer is above the 85th percentile of the wage distribution for their geographic location and age group would not be required to go through the PWD and PERM process, while EB-3 visa applicants would receive the same benefit if their wage offer is above the 90th percentile of the wage distribution for their geographic area and age group.

To implement this location and age-based wage rule, employers or immigrants file an LCA with DOL, and the department would compare the wage offer of an immigrant with the wage distribution of workers in his geographic area—what is usually called a Commuting Zone or a Labor Market Area. If his wage offer is equal to or higher than 90% of salaries earned by other workers in the Labor Market Area, DOL approves the LCA and the employer or immigrant can file form I-140 immediately, without the need to receive a PERM and PWD; but if the wage offer does not meet this test, DOL will request a PERM and PWD. Employers and immigrants can know with a great deal of certainty whether they meet this test before filing, by looking at Bureau of Labor Statistics and Census Bureau data. DOL can use its own discretion to set the age-group rules; in this report, I propose eight age groups of five-year intervals beginning with 25-year-olds through 64-year-olds, which is the range generally considered prime working age. Since some applicants will be younger than 25 or older than 64, I propose that the standard for 25–29-year-olds be applied to younger immigrants and the standard for 60–64-year-olds be applied to older ones. This avoids DOL using noncomparable U.S. citizens in those age ranges, who are often attending college or are semiretired.

To prevent immigrants and employers from gaming this rule by working remotely in low-wage locations, the rule should require the use of the higher of the two wage distributions of: (a) the location where the worker will live; and (b) the employer’s headquarters, if they are in different commuting zones.

For instance, this would mean that a 33-year-old engineer working on a start-up in an average urban area looking to get an EB-2 immigrant visa would need to receive a wage offer of about $104,000 to avoid the PWD and PERM process. A 30-year-old educator seeking an EB-3 while working on a temporary work visa for a high school in a rural area would need a salary offer of at least $72,000 to avoid the same process. Figures 6, 7, and 8 show the wage percentiles by age and rural versus urban distribution. the slots).37 EB-1 is exempted from this process because of its high eligibility threshold.

The Immigration and Nationality Act gives DOL broad authority in how it determines whether foreign workers will have an adverse impact on U.S. nationals. This proposed age and geographic wage formula for visa distribution can likely be implemented through regulation rather than requiring congressional action. This process reduces the timeline for obtaining permanent residency through an EB-2 or EB-3 visa from upward of 30 months to 12 months—and even as little as two months, if premium processing is also expanded to form I-485, as outlined in a previous Manhattan Institute report.[39]

This revamped and consolidated process has several benefits. It makes our high-skilled permanent residency categories more attractive to the highest-potential individuals by reducing their wait time. Second, it recognizes that the most highly paid visa holders are immigrants the least likely to negatively affect the job prospects of average Americans, and the most likely to be net contributors to the U.S. economy in the form of tax revenue, innovation, and entrepreneurship. Finally, by reducing the timeline to obtain a green card, it is less likely that a business will apply for an H-1B visa when seeking a permanent worker, reducing the artificial demand for this visa program, which is functioning as a gap filler for working immigrants while they wait for a green card.

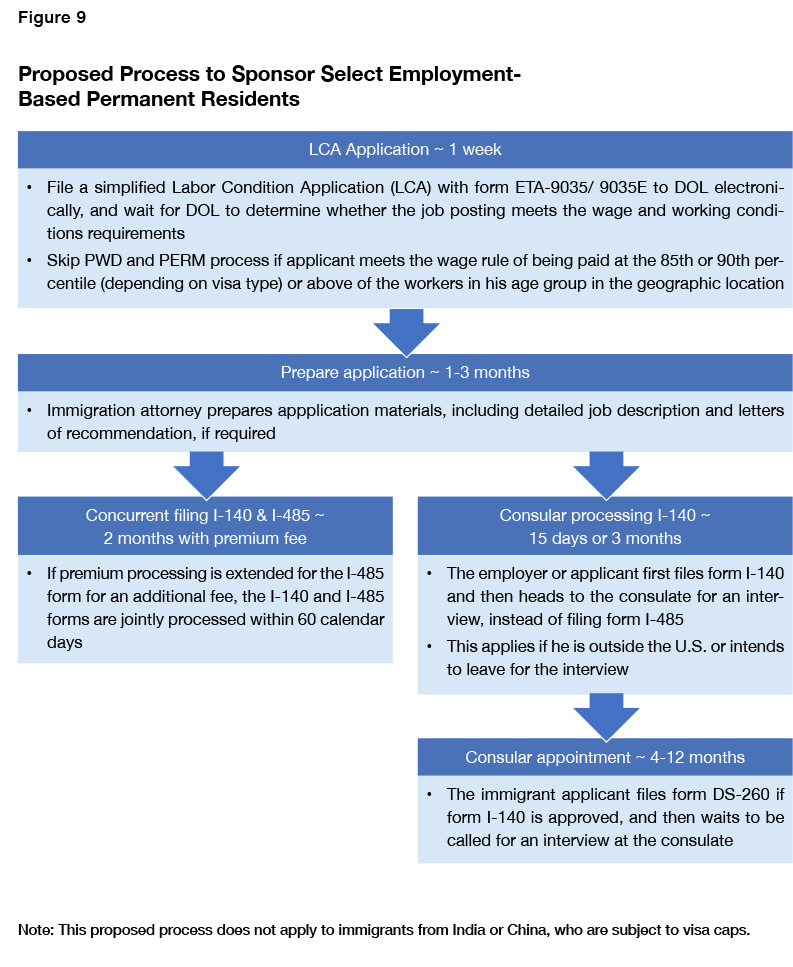

A New Path for Employment-Based Permanent Residents

If the proposals in this report are implemented, the process for employment-based immigrants to become permanent U.S. residents will be streamlined and attractive to immigrants and employers alike (Figure 9). Immigrants seeking EB-1 and EB-2 NIW visas would wait as little as four months under premium processing for adjustment of status. Highly paid seekers of EB-2 and EB-3 visas would wait as little as three months under adjustment of status and as little as eight months under consular processing.

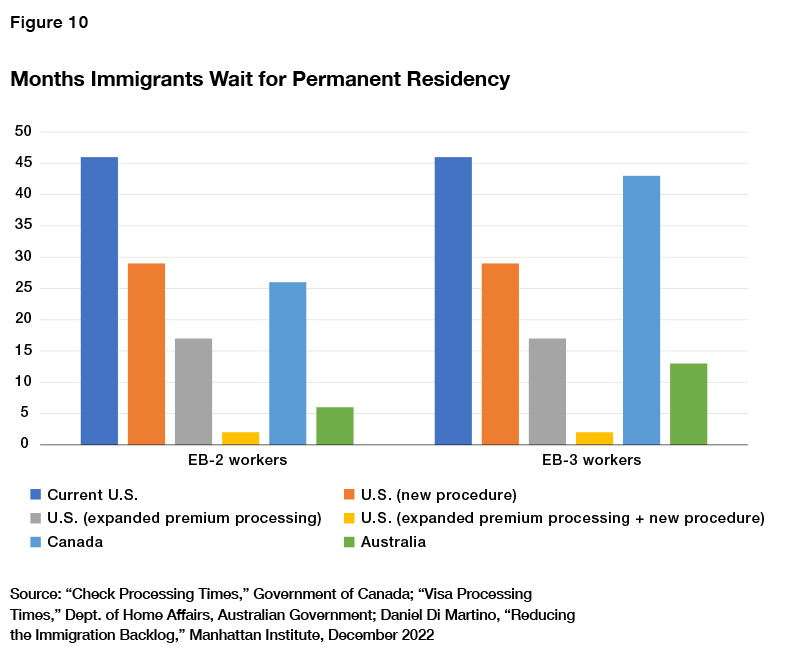

Exempting EB-2 and EB-3 visa applicants who meet a high wage floor (based on the wage distribution for their geographic location and age group) from the PWD and PERM process and implementing an expanded premium process (as I recommend in a previous Manhattan Institute report)[40] would drastically shorten the time it takes qualified immigrants to receive a green card and would make the U.S. immigration system even more efficient than that of some of our peer nations (Figure 10).

The new procedure for highly paid EB-2 and EB-3 applicants would shorten their processing times by over a third, from 46 months to 29 months. This is a good reform even if premium processing is not expanded. If the U.S. expands premium processing only to form I-485, it would shorten the wait time to 17 months. But if both reforms are implemented and highly paid EB-2 and EB-3 applicants are: (a) exempted from PWD and PERM; and (b) premium processing is expanded to form I-485, the whole permanent residency process can be shortened to barely two months.

Discussion and Conclusion

The U.S. is a coveted destination for highly skilled immigrants who are CEOs, lifesaving physicians, innovative engineers, and programmers. But the immigration system makes these productive people wait for years before knowing whether they can become permanent residents. Even investors who seek to bring millions of dollars to our shores and create jobs for American citizens are held back. Not only does the U.S. not give enough priority to those with the greatest potential economic contribution; the nation’s immigration system excludes nearly a million legal nonimmigrant students, spouses, and dependents from fully participating in the economy and society—even though they have been admitted and are living in the United States. Current immigration policy makes the U.S. a less desirable nation for the world’s best and brightest.

The U.S. should make the immigration process quicker for the most highly-paid migrants and allocate the limited number of visas available based on economic potential instead of random chance. And work visas to the U.S. must be made more attractive by expanding working rights to members of the nuclear families of high-skilled nonimmigrants. This report outlines how to reform the immigration system to attract immigrants and nonimmigrants with the greatest economic potential without changing the criteria for admission or the number of newcomers admitted.

These solutions, along with recommendations in my previous report on reducing processing times at USCIS, would put America at the forefront of the world when it comes to having a streamlined, high-skilled legal immigration system, ahead of foreign competitors like Australia and Canada. To attract the best and brightest:

- Allocate H-1B visa slots based on the percentile of the location and age-based wage distribution of nonimmigrants. This will reduce the uncertainty of selection for businesses and favor highly paid young nonimmigrants without biasing the program toward high-cost areas.

- Set aside part of the H-1B visa cap for new firms, shielding them from unfair competition from a few large tech companies and staffing firms.

- Allow H-1B visa holders to start working on any date after their petition is approved, in order to give employers flexibility.

- Apply the AC21 rule to the L-1 visa, which will indirectly reduce demand for H-1B visas.

- Grant work authorization incident to status to more than 150,000 spouses and children of F-2, H-4, J-2, and O-3 dependent visa holders in order to make high-skilled work, research, and study visas more attractive to families.

- Allow more than 700,000 international students on F-1 visas to start up and work in their own companies off-campus while they attend school, making international study in the U.S. more attractive to foreign students and unleashing the entrepreneurial capabilities of these students.

- Bypass the PWD and PERM process for highly paid immigrants to shorten processing time to obtain legal permanent residence by more than a year.

If implemented, the solutions in this report will ensure that the U.S. maximizes the economic benefits of the current level of immigration. This is the least that Americans should expect from their immigration system.

Endnotes

About the Author

Daniel Di Martino is a PhD candidate in economics at Columbia University and a graduate fellow at the Manhattan Institute, where he focuses on high-skill immigration policy. Born and raised in Venezuela, he came to the U.S. in 2016. He has appeared many times on national TV, including Fox News and CNN, and has written for USA Today and National Review. Di Martino speaks regularly on college campuses and at high schools. He received fellowships from the Institute for Humane Studies and the Job Creators Network.

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).