Homeless, but Able and Willing to Work How Federal Policy Neglects Employment-Based Solutions and What to Do About It

As the U.S. emerges from the Covid-19 pandemic, homelessness remains one of the most pressing challenges of cities. The many causes of homelessness—lack of affordable housing, untreated mental illness, un- and under-employment, incarceration and criminal recidivism, addiction—complicate the policy response.

For two decades, that response has been dominated by the “Housing First” philosophy. Housing First emphasizes immediate access to permanent housing with voluntary support services—yet no behavioral requirements. The most prevalent Housing First model is Permanent Supportive Housing (PSH), targeting the “chronically” homeless population, defined as those with long-term experience of homelessness, coupled with a physical or mental disability. In recent years, programs or housing models that do not operate in accord with Housing First principles or that do not target chronically homeless individuals have found it difficult to access government financial support.

Much of the debate over Housing First centers on its inability to reduce homelessness in prominent jurisdictions such as California. Acknowledging these high-profile shortcomings is important, but this debate has overlooked: (1) the impact of Housing First requirements in non-coastal, midsize cities; and (2) the impact of Housing First–centric policy for the non-chronically homeless population.

Through a case-study approach, this paper focuses on how federal Housing First requirements have complicated efforts to develop a holistic response to homelessness in three communities—Boulder and Aurora, Colorado; and Denton, Texas—and how these communities have, despite lack of access to federal housing resources, integrated alternative approaches to address homelessness, including community-based, employment-oriented approaches.

Notable findings:

- More than 70% of adult individuals experiencing homelessness do not meet the threshold of chronic homelessness and therefore do not qualify for PSH.[1]

- Mainstream homelessness assistance programs neglect the “middle third” of the homeless population—those who are not chronically homeless but who also will not resolve their homelessness on their own without at least minimal formal assistance.

- In communities that do not have access to major state and local resources to devote to homelessness, federal Housing First requirements are especially problematic. They frustrate community-based solutions and lead to policy fragmentation on the ground.

- The labor shortage underscores the value of work-oriented homelessness assistance programs.

- Local solutions that target unique segments of the non-chronically homeless population are possible, can be successful, and should be encouraged.

This paper focuses on the impacts of homelessness policy on the already unhoused and will highlight the Work Works model as an example of a complementary solution for communities seeking to build upon their current emergency programs and Housing First interventions that address homelessness. To ultimately prevent chronic homelessness, federal policy must be more inclusive of solutions beyond the Housing First approach in order to meet the diverse needs of people on the streets and in shelters.

Who the Homeless Are: Chronic vs. Non-Chronic, Coastal vs. Non-Coastal

More than 580,000 people experience homelessness on any given night in America, and more than 1.45 million make use of a shelter each year.[2] Many factors can contribute to homelessness. For example, people with histories of incarceration are nearly 10 times more likely to experience homelessness than the general public.[3] More than 70% of America’s homeless are unemployed, and even for many of the homeless individuals who are technically working at any given time, they are underemployed at a part-time or temporary job.[4] Homelessness also disproportionately affects people of color. Black Americans make up just 13% of the general population yet constitute 40% of the homeless population.[5]

For many housed Americans, homelessness evokes the image of someone with untreated psychosis living on the streets of San Francisco or Los Angeles, or in the New York City subway system. However, as Figures 1 and 2 show, that conception is not necessarily representative of people experiencing homelessness in their communities. Though a sizable minority do live in New York or California, most homeless Americans do not. And most are not considered chronically homeless.

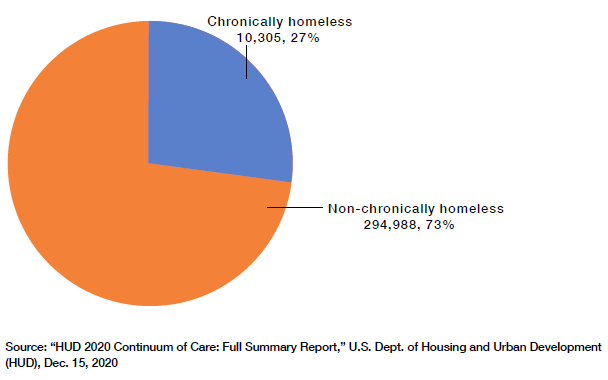

“Chronic” status requires a long-term experience of homelessness that is coupled with a disability.[6] Of the 405,293 homeless adult individuals (people outside a family unit) in 2020, 73% (294,988) were not considered chronically homeless.[7]

Figure 1

Chronically Homeless Adult Individuals vs. Non-Chronically Homeless Adult Individuals, 2020

Figure 2

Homeless Population in New York City and California vs. Rest of U.S., 2020

Stuck in the Middle: Who Housing First Doesn’t Serve

The federal government’s main source of homelessness assistance is the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) Continuum of Care program, which allocates close to $3 billion annually.[8] Continuum of Care is a system of local-level programs and services with the goal of most effectively deploying federal resources within a community. Continuum of Care programs coordinate applying for and administering HUD resources while the department defines the funding timeline, process, and project criteria. The federal funding comes with stipulations, including that recipient programs “use a Housing First approach.”[9]

Housing First (1) favors permanent housing programs, especially PSH; (2) prohibits mandated services or behavioral requirements, such as sobriety or compliance with case management, as a condition or expectation for receiving housing even if overall participation in the program or housing is voluntary; and (3) targets resources toward the chronically homeless.

Housing resources are scarce. A recent HUD webinar presented statistics from the 2020 Point in Time count, compared with available housing stock. It revealed that the U.S. lacks permanent housing resources for 85% of adults experiencing homelessness.[10] In other words, of 100 unaccompanied adults experiencing homelessness, only 15 will have access to housing in our current system. The supply of housing units is lower than HUD target goals partly because of the cost and length of time it takes to develop housing, but the scarcity is also due to the fact that HUD’s eligibility criteria prioritize the chronically homeless for access to federally funded programs, leaving many people ineligible even if the units did exist.[11]

Coordinated entry systems to collect data and match people to resources are mandated as part of the Continuum of Care. The VI-SPDAT (Vulnerability Index—Service Prioritization Decision Assistance Tool) is a survey used to score the needs of individuals and families based on age, physical and mental health, substance use, and length of time on the streets.[12] The tool generates a score that measures an individual’s vulnerability and is used to triage housing resources. Despite such tools, Continuum of Care systems are still required to follow the eligibility guidelines already set by public policy.

Coordinated entry for housing is helpful for the people who are eligible. The challenge is that—except for those who score extremely high on vulnerability scales and get referred to PSH, as well as those who score very low because of their ability to self-resolve with short-term rental assistance known as Rapid Re-Housing[13]—no HUD-funded resources exist to match people who fall into the middle. These populations are not chronically homeless, but neither are they successful with a short-term intervention. But this group of people can successfully resolve their homelessness with program solutions targeted to their needs.

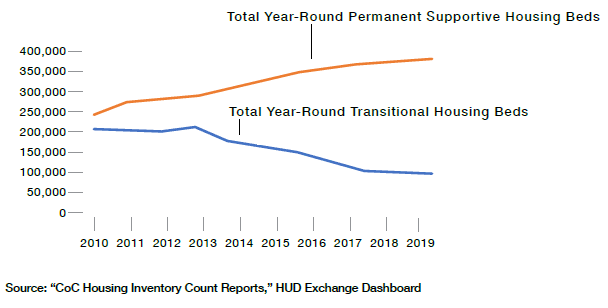

In the early 2000s, the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness (USICH) suggested that cities develop 10-year plans[14] to end homelessness by prioritizing Housing First.[15] The cornerstone of each plan was the development of PSH for people experiencing chronic homelessness, but often the plans omitted strategies related to treatment or employment interventions. During this time and in the years following, the number of transitional housing units (Figure 3) and dedicated financial support for transitional housing programs (Figure 4) declined. Transitional housing is a temporary housing model known for targeting that portion of the homeless population that is not chronically homeless but still needs assistance; usually, transitional housing is coupled with program support and requirements that promote and prepare people for eventual independent living.

Figure 3

Transitional Housing Units vs. Permanent Supportive Housing Units, 2010–20

Figure 4

Support for Transitional Housing Programs vs. Support for Permanent Supportive Housing, 2010–20

Federal funds are increasingly scarce for programs with wraparound supports focusing on, for instance, behavioral health and employment assistance. But because these interventions were still sorely needed to fully care for and support people experiencing homelessness, communities developed their own parallel systems through faith communities and nonprofits, many of which continue today.[16]

The result is a dual system leading to fragmentation and ineffective service delivery on the ground, the opposite of what was intended by the Continuum of Care approach. Due to the eligibility requirements mandated from the top, and reliance on Continuum of Care programs, elected city leaders have lost control over their local homelessness response. A survey of mayors by the Boston University Initiative on Cities found: “Mayors believe they are held accountable for addressing homelessness in their cities, but feel they have little control. Almost three-quarters of mayors (73 percent) perceive themselves as being held accountable by residents for local homelessness. Yet, only 19 percent believe that they have a lot of control over homelessness in their city.”[17]

Homelessness and the Labor Shortage

As of early summer 2022, there were roughly 11.3 million job openings across the nation, a 50% increase over the pre-pandemic high.[18] At the same time, about 6 million Americans were unemployed, indicating a labor shortage or a small pool of workers available to employers.[19] A tightened labor market has led to wage increases; for the year ending in June 2022, wages and salaries were up 5.3% over the same period, relative to 3.2% over the 12 months ending in June 2021.[20]

The labor shortage’s implications for the U.S. homeless population are often overlooked. If unand under-employment are one of the major risk factors for homelessness and if models that help people experiencing homelessness find jobs show promising results,[21] the ongoing labor shortage crisis represents a historic opportunity for that portion of the homeless adult population capable of economic independence. To provide maximum help to those cases would require investing in programs, such as transitional housing coupled with employment services, that have been neglected in recent years. Work Works America is leading one of the current movements focused on promoting employment-based solutions to address homelessness.

The Origin of Work Works

As the 1980s crack cocaine epidemic ravaged New York City and homelessness was on the rise, George McDonald, homelessness advocate and founder of The Doe Fund, spent 700 nights in a row handing out food in Grand Central Terminal. Every night, he heard, “Thank you for the sandwich. What I really need is a room and a job to pay for it.” In response, McDonald launched the first Work Works program—Ready, Willing & Able—known for the iconic “men in blue” who clean the streets of New York City while embracing work as a steppingstone out of homelessness.[22]

The Work Works theory of change is simple. When adults experiencing homelessness have the capacity to work and desire to resolve their situation, they can participate in a holistic program that combines paid work with transitional housing and supportive services for one year. Then they can reenter the mainstream workforce and obtain permanent housing, and they are far less likely to interact with the justice system.

Ready, Willing & Able still thrives in New York City, and five communities have adopted the Work Works model for their own needs, including Boulder and Aurora, Colorado; Atlanta; Washington, D.C.; and Philadelphia.[23]

Work Works programs serve the “middle third” of the unaccompanied adult homeless population. These individuals cycle in and out of shelters, jails, and hospitals and are in need of more support than what emergency shelters can offer. Yet these same individuals are not “chronic” or “vulnerable” enough to qualify for many homelessness assistance programs.

Work Works can be a successful intervention for a significant number of adults experiencing homelessness and seeking services. In 2021, according to annual Point in Time counts required by HUD, 194,749 adults were in a shelter. Nearly 23% (44,346 individuals) were considered chronically homeless.[24] Additionally, according to the National Alliance to End Homelessness, 30% of people who become homeless exit homelessness after two weeks.[25] Using these data, tens of thousands of people make up the “middle third”—those who could qualify for a Work Works program on any given night in the United States.

Work Works was built by people with lived experience who understand the struggle of living outside mainstream society. Over 85% of participants in the founding Work Works program are people of color, 88% self-report a history of substance abuse, more than 70% have a history of incarceration, and 25% had been unemployed for five or more years before joining the program.[26] Yet 0% reached the threshold to qualify for PSH.[27] An example: the Ready to Work affiliate in Colorado reports that 89% of program participants have a history of substance abuse, 71% have been incarcerated within the last seven years, 48% are people of color, and 78% have not been stably housed for more than one year.[28] Ready to Work Colorado also has a 72% graduation rate—meaning that three out of four adults who enter the program graduate with full-time jobs and independent housing. Over 80% are still housed one year after graduation.[29]

The Work Works Model

The defining feature of Work Works is work. This is significant for four reasons: (1) participants gain experience and earn an income; (2) businesses in fields such as food service or landscaping—known as “social enterprises”[30]—earn revenue to support the organization’s operations; (3) the act of working creates a positive dynamic for the individual while also improving public perception of people experiencing homelessness; and (4) the transitional jobs that a Work Works social enterprise offers prepare participants to join the mainstream workforce, thereby helping to solve labor shortages by acting as a bridge between marginalized people and employers.

Employment Experience

Work Works ventures integrate a social mission with a market-based, competitive, revenue-earning business, and they offer paid work and training for approximately 30 hours per week in practical fields. The enterprises can support up to 40% of total Work Works program operating costs through earned revenue.[31] This benefits the community but also proves that, when given an opportunity, nondisabled people experiencing homelessness can and want to contribute to building up their cities. Not only do program participants gain experience to add to résumés, but they also develop soft work skills and earn an income. They are empowered and benefit emotionally from the self-esteem derived from being integrated into the community through meaningful work. “Day by day, I believed I could do more,” one Work Works trainee told his team, “that I could get back to where I was before I experienced homelessness. I saw other people having success, and the staff believed I could, too.”[32]

A Safe and Stable Home

The second element of Work Works is housing: transitional accommodations in a dormitory setting for program participants. In several Work Works locations, commercial spaces have been converted into nontraditional housing stock in a cost-effective and expeditious manner. Work Works housing must be funded through local sources such as philanthropy and city- or state-flexible sources.

Living in Work Works housing provides a sense of community and a positive living environment to support participants as they transition out of homelessness or reenter from incarceration. Participants help maintain the property, and all Work Works housing is drug- and alcohol-free. Participants are voluntarily randomly drug-tested to ensure sobriety.

Supportive Services

In the third element of the program, supportive services, trainees meet with case managers and participate in life-skills training such as financial management, debt relief, and addiction recovery. Workforce development services include basic education and occupational training. Trainees are required to establish a savings account to ensure financial stability after they graduate and are living independently.

All these elements working in tandem form a “three-legged stool” and are required for Work Works to be successful.

Work Works is a complementary approach to other models, as it is designed to create opportunities for marginalized people not eligible for other forms of housing or support. This approach addresses four of the most pressing issues of our time: rising homelessness, mass incarceration, record unemployment, and racial inequity. And we know it works. Graduates of the original Ready, Willing & Able program in New York are 60% less likely to be convicted of a felony three years after graduation, compared with demographically identical individuals.[33] In Georgia, a 2020 study indicates that every $1 invested in Georgia Works yields as much as $3.44 in cost savings related to recidivism and incarceration and emergency-room visits.[34]

Community Involvement

Communities have found the Work Works model attractive for several reasons. First, the current array of interventions—emergency shelter, HUD-funded PSH, and Rapid Re-Housing vouchers—are not keeping pace with the need and are excluding a significant number of people experiencing homelessness. Second, local stakeholders are intrigued by the social enterprise component of the Work Works model and its ability to help with unmet local labor needs. Third, the model’s venture-based approach demonstrates to the community a proactive and mutually beneficial intervention that not only helps people in need but provides a benefit to the community overall through improved quality of life and public safety.

Municipal elected officials have to solve many difficult social and economic problems at once. Work Works is a tool to help them do that. When homelessness is solved for one person, the trajectory of an entire family is changed. When a community has the means to solve homelessness at scale, the impact is exponential.

Case Studies: Work Works in Practice

Much of the national media attention around homelessness has centered on California and New York. Those jurisdictions face profound challenges. But one way in which their experiences are not representative of homelessness throughout the U.S. is the significant state and local resources that they have deployed. Examples include New York City’s $2.6 billion “NYC 15/15” supportive housing program;[35] New York City’s shelters and programs to keep people out of shelters;[36] the $14 billion that California state government invested in homelessness programs in recent years;[37] and Los Angeles’s $1.2 billion Measure HHH initiative to pay for housing.[38]

California and New York are wealthy jurisdictions. Midsize cities not on the coasts have smaller tax bases, making them, in their responses to homelessness, more reliant on scarce federal resources. This creates tension between local efforts to respond to homelessness and Housing First requirements that focus on just a handful of interventions. That tension will be illustrated through the following case studies.

Case Study #1: Boulder, Colorado

Ready to Work has thriving sites in both Boulder and Aurora, Colorado, and is a founding member of the Work Works America Affiliate Network. The Work Works model helped transform the local response to addressing homelessness in the Metro Denver area.

Regional Context

Founded in 1994, the Metro Denver Homeless Initiative (MDHI) is the HUD-designated Continuum of Care program for the seven counties surrounding Denver.[39]

From 2000 to 2010, the number of people experiencing homelessness grew steadily in the region until, in 2010, the number of households experiencing homelessness was 6,189.[40] That year, frustrated community members, led by businesses and supported by Boulder city council members, adopted a camping ban. As a result, 1,676 citations were issued from 2010 to 2014.[41] Camping was banned in Denver in 2012.[42]

In 2010, Boulder County released its 10-year plan to end homelessness.[43] The overwhelming emphasis was Housing First and the development of units for the most vulnerable. At the time, there were 25 vouchers for PSH units and a goal to develop 100 more units.[44] Yet at the city level, the existing homelessness services, such as shelter and meals, were executed and coordinated by nonprofit organizations, with little participation or acknowledgment from local government employees. The adopted plan was silent on employment and lacked targeted strategies to offer pathways for people not (or not yet) chronically homeless.

The plan’s lack of visible action for the community became obvious when other factors (rise in the cost of living, marijuana legalization, Medicaid expansion in 2013) meant that street homelessness continued to increase.[45]

Coordinated Entry in Metro Denver

All of the 3,853 PSH units in the Metro Denver area are subject to a single coordinated entry system that uses VI-SPDAT.[46] The tool scores people on a 17-point scale based on time spent homeless, age, and tri-morbidities (substance abuse, mental illness, and physical health).[47]

Due in large part to criteria set by the Continuum of Care for housing eligibility and the scarcity of units, if a person seeking help does not score higher than an 11 or 12, he or she has a minimal chance of securing housing. Conversely, Rapid Re-Housing resources are handled through the same system. To be eligible in that case, a participant needs to score low enough (for example, by not experiencing substance abuse or short-term homelessness) to show that he or she can assume the rent after three to six months. Rapid Re-Housing is designed to be a brief housing subsidy for people who are situationally homeless due to loss of income and who are not facing other significant barriers to employment or housing.[48]

The population that falls through the cracks are the “middle third.”[49] These are people who meet many criteria (drug use, long history of street homelessness) but are too young and not mentally ill. They would score in the 7–10-point range on a VI-SPDAT.

This is how HUD policy plays out on the ground. The Continuum of Care skews toward PSH, and the coordinated entry system acts as gatekeeper for the limited number of units. In communities without robust shelter systems, many people are simply on the street and out of luck. The community overall suffers from friction over camping and related challenges with public disorder.

Identifying a Need

In 2022, Bridge House’s Ready to Work program celebrated 10 years of impact. Launched as an enhancement to Boulder’s response to addressing homelessness and then scaled with a second location in Aurora, Ready to Work changed the conversation in Metro Denver about creating a multifaceted strategy to address homelessness. It now serves as the primary example for how small and midsize cities across the country can adopt a Work Works solution.

From 1996 to 2011, Bridge House was a small, basic-needs nonprofit organization providing day shelter and meals to adults experiencing homelessness in Boulder. Boulder has a unique culture built upon a history of liberalism and a pioneer spirit that is now in conflict with community concerns about creating policies that attract people to Boulder who cannot afford to live there. The hobo culture in Boulder dates back to the mining days of the 1800s. Today, debates about who belongs and who is worthy of services are intense; yet few of its 110,000 residents are natives of the city.[50]

In 2011, like many communities of its size, Boulder had an existing network of faith-based communities and nonprofit organizations that responded to address homelessness, but with little or no coordination with city officials. At that time, homelessness services in Boulder consisted of one shelter—the 160-bed Boulder Shelter for the Homeless—an overflow shelter run by Boulder Outreach for Homeless Overflow (BOHO), and a day shelter at the 1,200-square-foot carriage house downtown leased to Bridge House by the First Congregational Church. HUD Point in Time counts indicated that 1,050 people were experiencing homelessness in Boulder County,[51] and 100 people sought services at the tiny carriage house on a daily basis. Based on intake data for day shelter case-management services in Boulder in 2011, approximately 80% of people were unemployed and 50% were actively seeking employment.[52] For these people, income from employment would be the primary means to secure and maintain housing, as they do not qualify for disability. Without enough shelter beds or other opportunities to provide, Bridge House leadership sought more solutions.

The staff and board of directors at Bridge House wanted to deepen the organization’s impact by developing more robust case-management options, including access to employment for its clients. People seeking employment often lacked a stable place to sleep and the tools to keep a job. The fragmented nature of local shelter programs exacerbated these challenges in Boulder, as it does in many other communities.

Over the spring and summer of 2011, Bridge House leadership explored employment-based programming and adopted the Work Works model to launch their program, called Ready to Work.

The Ready to Work Response

At the time, the prospect of increased HUD funding for transitional housing and supportive services, including job training, became unlikely; as Figure 5 illustrates, major cuts were looming. Therefore, Bridge House had to embark on a due-diligence process to determine feasibility of launching with local resources alone. Outreach was conducted to determine the interest of the City of Boulder to hire work crews to perform maintenance and cleanup services; private, individual donors made commitments to fund the project; other service providers indicated interest in providing referrals; businesses expressed the desire to support an effort to get people to work; and Bridge House confirmed that a sizable number of people experiencing homelessness in Boulder were not only interested in, but were seeking, a program of this kind.

Figure 5

Funding for Transitional Housing, Metropolitan Denver Homeless Initiative, 2005–20

Ready to Work launched a pilot program in January 2012, after raising $75,000 in seed funding and obtaining permission from the City of Boulder to provide cleanup services on its iconic Pearl Street Mall, in the heart of the downtown business district. The agreement specified that Ready to Work would provide a crew of five trainees, people experiencing homelessness identified as people in the “middle third.” Ready to Work would cover all the costs of the program for six months. If the crew was successful, the city would consider a paid contract after the pilot.[53]

The crew worked 20 hours a week and engaged in supportive services for an additional five hours a week. Trainees were paid minimum wage and provided with meals, showers, clothing, and bus fare. Trainees were oriented to program expectations and provided with uniforms and gear. All services were provided out of Bridge House’s carriage-house day shelter location, and no housing was provided.[54]

After a successful first six months, the City of Boulder was so impressed that Ready to Work obtained a paid contract with the City of Boulder Parks and Recreation department. The outdoor crew was born as a revenue-generating social enterprise that set the stage for the expansion and future impact of the program—on the lives of the people involved and also on the community as a whole.

In the fall of 2012, impressed by the model and early results, a local philanthropist gave Bridge House a sizable grant to develop a commercial kitchen to combine Bridge House’s mission to provide meals to low-income and food-insecure individuals with the job training and earned-revenue model. The result was Community Table Kitchen, which launched in 2013 with three goals: to provide access to nutritious meals for low-income people, to provide training and jobs in the culinary arts for Ready to Work trainees, and to earn revenue to support the organization. In 2013, Ready to Work expanded its outdoor crew social enterprise with contracts for services from the City of Boulder Open Space and Mountain Parks, as well as the local housing authority, Boulder Housing Partners.

With the opening of Community Table Kitchen in September 2013 and the addition of culinary arts job training, Ready to Work expanded its capacity from five to 16 paid trainee positions. Ready to Work also deepened the impact of the program by partnering with the Addiction Recovery Center for sobriety support services, given the extreme overlap between substance-use disorder and Ready to Work trainees.

Expanding to Housing

Understanding that Ready to Work needed to offer housing to continue growing, Bridge House leadership started searching for housing that was practical, affordable, and well positioned to promote the culture of Ready to Work. The program’s leadership approached Boulder Housing Partners, the local housing authority; and MDHI, the local HUD Continuum of Care. But because of the lack of obvious funding for this nontraditional model serving a low-priority population, both entities declined the opportunity to participate.[55]

Undeterred, in 2014, Bridge House raised funds to purchase 4747 Table Mesa Drive in Boulder. This 14,000-square-foot office building would be converted into congregate, transitional living for 44 Ready to Work trainees. Bridge House raised $4.3 million for the project: about $2 million was raised through state and local government sources, and $2.3 million was raised from private individuals.[56] The facility opened to trainees 11 months after purchase, making the Ready to Work House one of the fastest and most cost-effective housing initiatives in Boulder. For comparison, one year earlier, the Lee Hill project opened 31 units of HUD-funded PSH at a cost of $8 million and after three years of development and controversy.[57]

On August 12, 2015, Ready to Work House and Employment Center became the true epicenter of the Ready to Work culture of opportunity.[58] Program participants were not only safe and off the streets but were also able to form a community, go to work each day, build a résumé, save money, build a rental history, stay sober, address barriers to employment and housing, and be empowered to succeed—all in one place. According to one successful Ready to Work graduate, when he moved into the House, “I had not slept in a bed in over 2 years and it took some adjustment for me to learn how to live a stable life again.”

In 2016, one year after opening Ready to Work House in Boulder, the program graduated 43 people into full-time jobs and permanent housing, with a success rate of 77%.[59] That year, Ready to Work also won the prestigious Eagle Award for Innovation in housing from the state of Colorado, in recognition of the organization’s contribution to the state’s homelessness response.[60]

In 2017, Ready to Work continued to lead the region in workforce programming and services for adults experiencing homelessness, and 49 people graduated from the program. Also that year, Ready to Work social enterprises provided 46,000 labor hours and earned $784,361 in revenue, constituting 65% of the Ready to Work Boulder budget.[61]

Simultaneously, sheltering options were changing in Boulder. Due to funding cuts in exchange for a Housing First strategy, shelters had to make do with reduced resources, leaving the city with fewer sheltering options. In response, Bridge House, in collaboration with BOHO and the Boulder Department of Human Services, created the Path to Home program. Path to Home was Boulder’s first 24/7 shelter that offered nightly emergency shelter as well as intake, assessment, and navigation case management for all clients. By overseeing the entry point, Bridge House was able to effectively assess people experiencing homelessness and use a data-driven approach to analyze the population in terms of need, eligibility, and capacity. According to data collected at Path to Home from 2017 to 2020, of the 3,530 persons screened for the City of Boulder, only 1,216 (35%) were PSH-eligible and referred for housing. Of these, just 193 (16%) received PSH.[62] Meanwhile, over the same period, 124 people graduated from Ready to Work—72% of those referred to the program.[63]

Case Study #2: Aurora, Colorado

In 2017, following the success of Ready to Work Boulder, several foundations asked Bridge House to expand the Work Works model to a second location in Metro Denver. With a population of 386,000,[64] Aurora, Colorado, is the third largest city in the state and three times larger than Boulder. Ready to Work announced expansion plans for the development of a second Ready to Work House with capacity for 50 more jobs and housing opportunities, bringing the total capacity from 44 to 94 in the region.

Aurora had invested in emergency shelter yet lacked housing-based services for the majority of people experiencing homelessness. Based on 2017 Point in Time data, 459 people were homeless in the city, constituting nearly 9% of the metro region’s 5,116 homeless.[65] Of those experiencing homelessness in Aurora, 111 (24%) were chronically homeless, and another 37% were homeless for less than one year, making them ideal candidates for a Work Works model. In Aurora, people with a history of incarceration lacked opportunities, and 24% of all parolees in Colorado were homeless and unemployed at the time of their release in 2017.[66] Also, people of color represented a disproportionate number of people on the streets, with 36% of Point in Time respondents identifying as black, compared with 16% in the city’s overall population.[67]

Expanding the Work Works Model

As in Boulder, Aurora elected officials and heads of key departments such as Parks, Recreation and Open Space were excited about the multifaceted Work Works model. The community also embraced the concept. As Skip Noe, former Aurora city manager, later said: “Ready to Work and the Work Works model helped our community take an important step toward ending homelessness. From a manager’s viewpoint, it addressed multiple problems, was based in collaboration, attracted a broad base of support, and produced great results.”[68]

Ready to Work Aurora became a reality when Bridge House purchased 3176 S. Peoria Court. Renovations began in July 2018 for a new 50-bed facility, which opened in December 2018. Immediately, Ready to Work Aurora secured employment for residents through the City of Aurora Parks, Recreation and Open Space Department. Later, Ready to Work secured work opportunities with the City of Aurora Neighborhood Services and Forestry Departments. For both Boulder and Aurora, Ready to Work converted commercial office buildings into community living with a private living space at 28% of the cost of building traditional units[69]—and all through non-HUD funding sources.

By 2019, the Ready to Work programs in Boulder and Aurora had different trajectories. Ready to Work Boulder focused on refining the program model and further solidifying practices and protocols that have achieved excellent outcomes. Ready to Work Aurora focused on implementing the Ready to Work three-legged stool and culture. The journey of each program location was different in 2019; but by the end of the year, the programs came together to form a single model with two locations in Metro Denver. The need and ability for the model to work in such different markets demonstrates a need in most communities for Work Works.

A Culture of Success

Ready to Work Colorado achieved a 72% graduation rate in 2019.[70] Successful graduation is defined as a trainee achieving program milestones and obtaining a job with a mainstream employer, permanent housing outside a Ready to Work location, and having the ability to maintain both. In the areas of community relations and social enterprise, both Boulder and Aurora thrived. In 2019, the Boulder outdoor crew completed its seventh year as a contractor for the City of Boulder and performed over 40,000 labor hours beautifying the community. In Aurora, the outdoor crew executed on the goal to develop a working partnership with the City of Aurora and successfully completed the first year of operations for the Colfax Business Improvement District. Community Table Kitchen earned over $500,000 in revenue and remained a key employment opportunity for trainees from both locations.[71]

The year 2020 began with promise. Both Boulder and Aurora sites had assembled excellent program teams, and Aurora was entering year two, allowing for the program to be fully operational for impact. In the first year of operation, 12 trainees graduated from Ready to Work Aurora, with an average starting wage of $14.79 per hour ($2.79 more than the Colorado minimum wage).[72] Work contracts were secured, and Community Table Kitchen planned to expand, which would increase training and revenue opportunities for Ready to Work.

Then came March 2020 and the Covid-19 pandemic. Instantly, Bridge House programs had to adapt. The Ready to Work program was in a unique situation because it operates as both a service provider and a small business. Despite the challenges of the pandemic, both sites are continuing to thrive in 2022. In 2021, the two sites provided 31,340 nights of housing, earned over $1.4 million in social enterprise revenue,[73] and embarked on a partnership with municipal leaders from the cities of Littleton, Sheridan, and Englewood in Metro Denver to develop a third Ready to Work site.

Case Study #3: Denton, Texas

In Denton, Texas, a feasibility study is under way to determine how the Work Works model can complement the community’s existing efforts to address homelessness. This process includes assessing who is experiencing homelessness, the scope and results of available services, and an exploration of the earned revenue potential of a Work Works social enterprise.

An initial Work Works feasibility study was completed in May 2020. Since then, a number of local factors have created the conditions for Work Works to take hold, including the development of a city agency dedicated to building out a coordinated response to homelessness and the consolidation of basic-needs nonprofit organizations. The following case study maps the original context from 2019 to the present.

Situational Context

Denton is a city of approximately 148,000 residents and is in the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex.[74]

As with many communities of its size, Denton’s approach to homelessness has grown organically over time to address basic and emergency needs, with some outside support from the regional Continuum of Care administering HUD funds. Denton is part of Denton County, and the local Continuum of Care is called the Texas Homeless Network, a program covering 215 of the state’s 254 counties.[75] The local convening group to address homelessness is the Denton County Homeless Coalition, comprising nonprofit organizations and led by the United Way. As with many communities, the local Continuum of Care focuses on housing the most vulnerable, with a particular emphasis on veterans. In 2021, the Continuum of Care reported 1,111 PSH units (1,063 for veterans) and 494 Rapid Re-Housing vouchers for all its 215 counties.[76] The 2021 Point in Time survey recorded 2,562 people experiencing homelessness in shelters, including 1,288 unaccompanied adults.[77] The majority of shelter resources are provided through nonprofit and faith-based organizations. According to the Continuum of Care data for 2021, less than 40% of shelter beds are recorded in the Homeless Management Information System, suggesting that a good portion of services are not receiving HUD support. This presents both an opportunity and a challenge to add a Work Works model into the local response.[78]

At the beginning of the Work Works 2019 feasibility study, there were two primary sheltering agencies: Monsignor King Outreach Center (MKOC); and Our Daily Bread (ODB). MKOC offered night services, and ODB offered day shelter, meals, and limited case management. A Salvation Army location also provided services but without much overlap.[79]

Ready to Work team members visited the community in February 2020 and, based on conversations, observed programming. A review of use data compared with income data found a clear need for housing options that could help people exit the shelter system, as well as a need for workforce solutions. From a review of program data shared by local service organizations with the Denton County Homeless Coalition, most services being provided focused on meeting basic needs and did not directly result in permanent housing for their clients. Services at MKOC had recently been limited to 30-day increments because of increased demand. At ODB, new leadership, high demand, and a need for space were also pointing to a new emphasis on case planning and a desire for exit opportunities for clients.

MKOC and ODB both stated that employment resources were scarce. The primary cause of homelessness for 24% of the population is loss of job and/or unemployment, according to the 2019 Point in Time survey.[80] At the same time, 37% of the people on the local housing priority list reported having no disability that would prohibit them from working.

According to 2019 data from service providers, 62% of basic-needs clients reported zero income; for those with income, the monthly average was $777 per month.[81] Based on the data of 1,600 individuals using both Salvation Army and ODB services, 341 individuals using MKOC over a 12-month period (March 2019 to March 2020), and 379 on the housing priority list, it is evident that a significant portion of the population is not placed on the housing priority because of HUD criteria for eligibility for vouchers. The number of clients on the housing priority list versus the number of clients using daily basic-needs services indicates a gap that Work Works exists to fill.[82]

Just as the initial Work Works feasibility study was published in May 2020, the city purchased a site to consolidate sheltering services and create a one-stop shop to promote the efficiency and effectiveness of sheltering interventions. In September 2020, ODB merged with MKOC and absorbed a city-sponsored quarantine site at a local motel for homeless individuals who tested positive for Covid-19. This was a positive step from the service provider community and the city to streamline services.

ODB currently operates in three locations in Denton, serving people experiencing homelessness from the region. ODB’s low-barrier (e.g., no program participation, work, or sobriety requirements) location serves three meals a day, seven days a week, averaging 700 meals a day and totaling over 250,000 meals a year. ODB offers a continuum of services. Programming consists of meals, emergency and enhanced shelter, case management, housing assistance, identification documentation assistance, prescription medication assistance, transportation assistance, mail service, laundry and showers, hygiene and clothing, referral and connection to legal services, financial services, employment services, benefits providers, and medical services.

Beginning in December 2022, ODB will operate all services at a new city-owned Denton building.[83] This new facility will be the only 24/7 low-barrier shelter in the county and will include capacity for enhanced shelter to provide stable beds for people engaged in employment programming. The city’s proactive approach to organizing local stakeholders is an example of a community innovating outside the Continuum of Care and leveraging local resources to do so.

ODB and Ready to Work are now partnering to launch a Denton Work Works program. As part of the city’s commitment to innovate in its response to homelessness, officials released a Request for Qualifications for a work-based program. In the request, the City of Denton Department of Parks and Recreation cited a need for labor and a commitment to creating pathways for people experiencing homelessness. ODB responded to the Request for Qualifications with a proposal that partners the local organization with Ready to Work.

The goal is to launch a Work Works pilot in late fall 2022 with a contract with the City of Denton. A portion of the beds at the new facility will be designated for Work Works housing. There is both political will and local nonprofit capacity for Work Works to come to Denton. While this city has supported the employment-based model, the process would be smoother, and the impact could be even greater if the model were recognized and supported by the Continuum of Care.

Conclusion

The above-mentioned case studies illustrate how work-oriented homelessness assistance programs not only benefit their target population but also the larger community—through earnings, cost savings, increased labor hours, and more available housing. Ready to Work is solving for much more than homelessness. The three-legged stool of the Work Works model provides primary and secondary benefits to the community. Its philosophy and implementation design allow for community integration and buy-in in a way other strategies cannot.

Ready to Work has benefited both private and public stakeholders, yet the lack of a federal funding stream to launch and operate the model has deterred its growth. The communities with Work Works affiliates in Colorado, New York, and Georgia have been able to have a positive impact on vulnerable people in those particular locales; but for Work Works and other non–Housing First approaches to be available to more communities nationwide, federal policymakers must embrace a more innovative and dynamic Continuum of Care that enables communities to access more abundant and flexible resources.

If federal policy encouraged additional interventions beyond Housing First, states and cities would have more flexibility to meet their local needs by prioritizing cost-effective, integrated, and pragmatic solutions that result in long-term, positive outcomes for the overall community. These interventions could include nontraditional forms of housing such as converted commercial spaces, dormitories, or tiny homes that currently do not qualify for federal support because they are not traditional units, as well as models that target specific segments of the homeless population with services attached to transitional housing that do not currently qualify because they require program participation. Both approaches are necessary to meet the diverse needs of people on the street. A more inclusive federal attitude to embrace more than Housing First solutions would incentivize local innovation to develop creative housing models and programs that combine services with housing alternatives.

Additionally, to increase funding for broader approaches to addressing homelessness, federal agencies such as the U.S. Department of Labor and the U.S. Department of Justice need to participate in a coordinated way with HUD to fund holistic models. The circumstance of homelessness is connected with the inability for people to be stable in other areas of their lives. Therefore, housing alone cannot solve homelessness. Communities need tools that address the root causes of homelessness and that remove the barriers people face in getting permanent housing—and keeping it, once they have it. These barriers include un- and under-employment, addiction, mental illness, and lack of access to behavioral health care. The U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness (USICH) provides a forum for collaboration between federal agencies. To meet today’s demand for on-the-ground solutions that reach more than just the Housing First–eligible population, USICH must lead agency collaboration to promote support for the populations not served by current models.

Work-based programs and solutions can develop relationships between local employers and municipal governments. These relationships can solve immediate labor shortages by filling vacant positions while investing in and developing career pathways to living-wage jobs in growing sectors. Models such as Work Works help people earn a wage and GEDs and other credentials; they also empower people to integrate back into the mainstream of a community. This has social and financial benefits not only to individuals but to entire communities.

As we know, homelessness is not yet eradicated; in fact, it is getting worse. The number of unsheltered people is growing, and, as the price of housing continues to rise in disproportion to household earnings, our attempts to prevent homelessness and intervene with traditional housing resources are failing to keep pace with the need. Employers are struggling to find workers. Residents of downtowns are fearful of the growing presence of disorderly encampments and active drug use.

We need fresh, bold solutions to combat this crisis, especially those that promote collaborative approaches across federal agencies. We can empower communities by arming them with an array of best-practice models, flexible policies, and funding that encourages innovation while leveraging the support of a broad spectrum of local stakeholders. With coordination, we can solve many interrelated problems at the same time. We must be open to new ideas that enhance existing Continuums of Care and that provide more tools to serve people experiencing homelessness.

About the Author

Isabel McDevitt leads Work Works America, a capacity-building effort to bring the award-winning Work Works employment-based solution to communities seeking to reimagine their approach to addressing homelessness. She has founded and operated four social enterprises and has developed more than 150 units of nontraditional housing, including the conversion of commercial spaces for people transitioning out of homelessness. McDevitt has served as executive vice president for The Doe Fund in New York and as chief executive officer for Bridge House in Metro Denver Colorado, where she founded the Ready to Work program.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Stephen Eide of the Manhattan Institute for his guidance, expertise, and input and Thomas Triedman for his help with the labor-market research.

Endnotes

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).