Crime-Fighting Lessons from Summer Youth Employment Programs

New York City is home to the nation’s largest Summer Youth Employment Program (SYEP), an annual undertaking that connects 75,000 young adults to jobs each summer. This program, like others around the country, provides remuneration to participants and work for employers, but it also has long-run impacts. Specifically, a large body of high-quality research shows that SYEPs significantly reduce participants’ propensity to commit crimes.

This report reviews what research has revealed about SYEPs based on experiments from New York and three other major cities. These experiments show that these jobs programs do not affect participants’ educational attainment or labor-market value, but they do reduce their propensity to commit crimes, both during the program and after the program has ended. I discuss possible causal mechanisms and the limits of the extant research on this vital subject. Lastly, I call on NYC’s leadership to use its SYEP—the nation’s flagship program—as a laboratory to better understand and improve these programs, by investigating these questions:

• What component of SYEPs actually lead to their crime-reducing effects?

• What part of SYEPs’ effect on crime is driven by participants who are most at risk of offending, and how can the programs best serve those participants? Could the programs be more successful if they would focus primarily on at-risk young adults, or does exposure to a non-risk peer group drive the effect?

• How often, and for how long, should SYEPs be administered, including outside the summer months?

Introduction

New York City’s Summer Youth Employment Program (SYEP) is the largest, and one of the most influential, such programs in the country. [1] Operating since 1963, it today employs some 75,000 New Yorkers aged 14–24, covering six weeks of $15-an-hour work for public, private, and nonprofit employers, at a cost to the city of $134 million. [2] During his campaign, New York’s new mayor, Eric Adams, called for expanding the program year-round, claiming that it helps “youth develop crucial skills, which lead to better criminal-justice, academic, and employment outcomes,” as well as directly aiding struggling families. [3]

SYEPs like New York’s have recently attracted national attention as part of a campaign to “defund” the police. Pointing to research that finds participants less likely to offend, advocates argue that this is proof that investing in employment (and, by extension, government investment generally) can combat crime as efficiently as (if not more efficiently than) the police.[4]

With a multimillion-dollar expansion of New York City’s SYEP potentially in the works, and with these programs in the national spotlight, it is worth asking: What are the short- and long- term effects of SYEPs? Do they, as Adams suggests, improve criminal-justice, academic, and employment outcomes? What are the costs and benefits of the programs, and how do they actually work?

The primary benefit of SYEPs emerges not from academic or labor-market returns—which are weak or nonexistent—but from dramatic impacts on participants’ propensity to commit crimes relative to nonparticipants. These effects appear in New York City’s program and in programs studied in other major metros: Boston, Chicago, and Philadelphia.

How SYEPs Operate

Government-funded and organized employment for teens and young adults is not new. During the Great Depression and World War II, the National Youth Administration (a subsidiary of the Works Progress Administration) employed nearly 5 million Americans aged 16–25. [5] Summer jobs programs for youth appear in the federal budget as far back as 1964 and were incorporated into the annual Youth Activities budget in 2000. [6] In recent years, a dramatic decline in youth employment has generated renewed interest in the programs. The share of 16–19-year- olds who are employed has fallen 11 percentage points since 2000 and is now roughly half the overall employment-to-population ratio; [7] teen employment during the summer, though reliably higher than during the school year, has also systematically declined. [8] Such declines prompted Congress to include $1.2 billion for youth employment in the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act and to authorize further spending under the 2014 Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act. [9]

Today, SYEPs appear across the country. In 2017, 27 of the 30 largest cities in the United States had them. [10] Even very small jurisdictions—such as Missoula, Montana, Erie County, Pennsylvania, and Evanston, Illinois—operate programs. [11] Most are run the same way: the administrator, usually a local government, connects teenagers and young adults to work with private, public, or nonprofit entities, with wages fully paid or subsidized by the administrating government. Many programs also include workforce preparedness training, socio-emotional education or other emotional skills training, or access to a dedicated adult mentor.

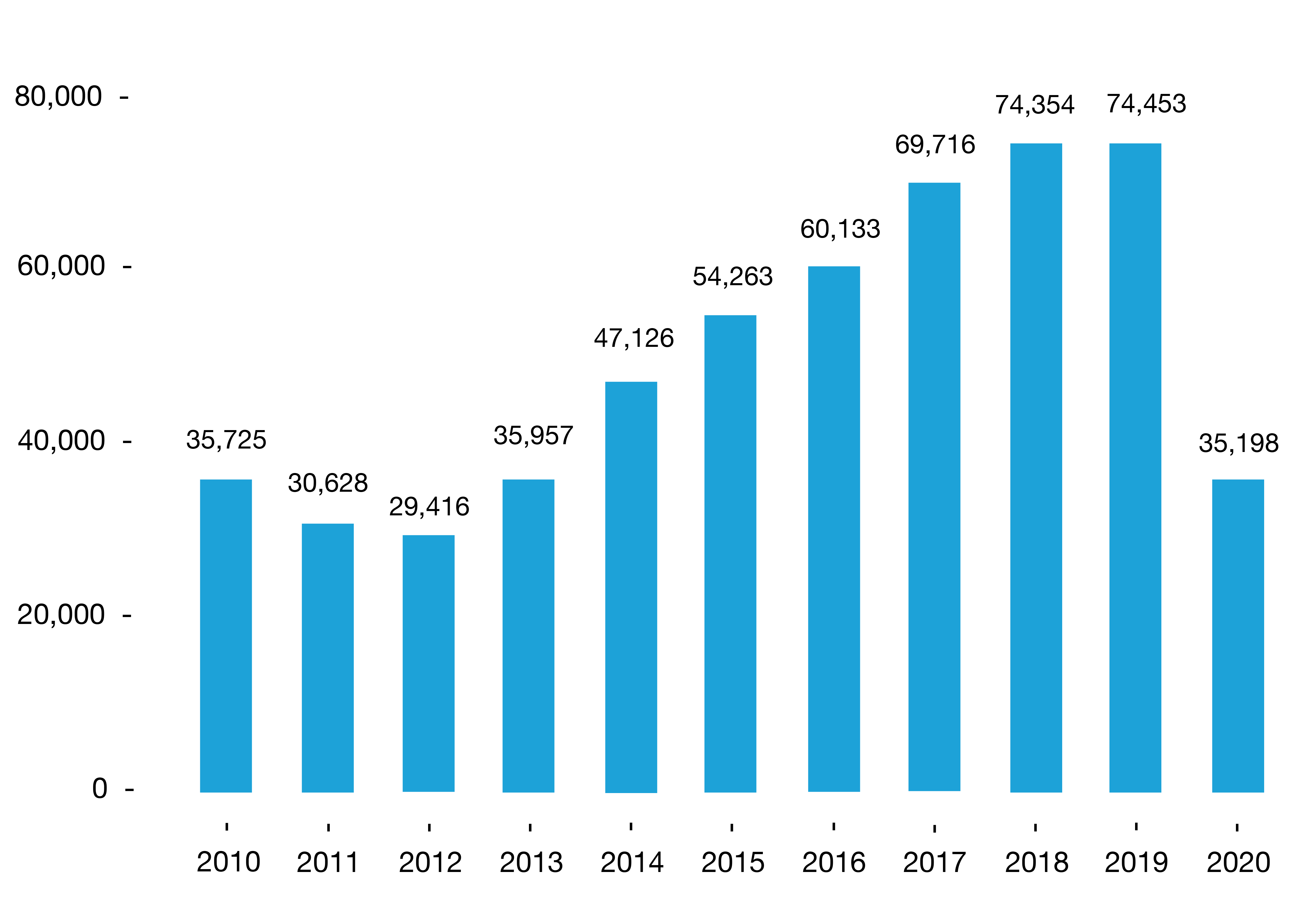

New York City’s SYEP is, by available estimates, the largest in the country. In 2019, the most recent full year of implementation for which data are available, it admitted 74,453 participants out of 151,597 applicants (Figure 1). That represents a dramatic increase from 2010, when 35,725 participants enrolled. Program funding has kept pace with growing enrollment: the 2019 program cost roughly $164 million, up from $45.5 million in 2013. [12]

Figure 1

NYC Summer Youth Employment Program Enrollment, 2010–20

Source: Summer Youth Employment Program 2019 Annual Summary,” NYC Department of Youth & Community Development; “2020 SYEP Summer Bridge Annual Summary,” NYC Department of Youth & Community Development

The participants in 2019 matched the city’s diversity: 44% were black, 25% Hispanic, 15% white, 12% Asian, and 4% other. Girls overrepresented boys, 57% to 43%. Most participants were from Brooklyn (39%), the Bronx (23%), and Queens (22%); 10% were from Manhattan and 6% from Staten Island. The city runs a subprogram, Vulnerable Youth, targeted at young adults who are homeless, in foster care, or have a criminal record, or whose families are receiving preventive services. Another subprogram, MAP to $uccess, works directly with the New York City Housing Authority to enroll participants living in high-crime public housing; some 3,000 of these young adults enrolled in SYEPs in 2019. [13]

Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, the city dramatically curtailed its SYEP in 2020, running an entirely virtual “Summer Bridge” program. The cohort was much smaller than in 2019, and the city had only mixed success at keeping at-risk young adults involved. Overall enrollment dropped by 53%, while enrollment through MAP to $uccess fell by 32%, and enrollment in Vulnerable Youth (renamed “Emerging Leaders”) fell 52%. [14]

In normal years, participants work at more than 13,000 enrolled work sites, 46% of them in the private sector, 39% in nonprofits, and 15% in public agencies. The share of private-sector employers has risen steadily since 2010, when it was 28%. In addition to their jobs, participants receive preemployment training, which focuses on skills such as work readiness, teamwork and conflict resolution, and practical skills like financial literacy. [15]

Of those enrolled, 14 and 15-year-olds receive jobs-and-skills training, as well as a small stipend. Participants 16 and older work 25 hours a week in “diverse and developmentally appropriate work experiences that connect to one of the city’s priority sectors, foster civic engagement, skill building and exposes [sic] youth to promising career pathways.” They receive the state minimum wage of $15 an hour. Some enrollees also participate in the city’s “Ladders for Leaders” program, a special internship for high-achieving high school and college students. [16]

That a program is widespread is, of course, not evidence of its efficacy. But SYEPs are the rare policy intervention that is both popular and effective. Many programs that work in one locale fail when scaled up. SYEPs, by contrast, have shown significant positive effects in all the high- quality studies investigating them in recent years.

What Summer Youth Employment Programs Do (and Don’t Do)

The highest-quality evidence on SYEPs comes from studies of city programs that admit applicants through a lottery and then track the outcomes of those who are and are not admitted. The lottery allows researchers to ensure that the applicants admitted (the treatment group) do not vary systematically from those not admitted (the control group) in a way that would introduce selection bias, thus allowing isolation of the causal effect of SYEP participation. (Strictly speaking, these analyses assess the causal effect of admission, not of participation, because some who are admitted could opt out—what social scientists call an “intent to treat” analysis. I use the term “participant” throughout this report, but this distinction needs to be noted.)

This review relies primarily on evidence from 11 studies, covering SYEPs in four cities—New York, Boston, Philadelphia, and Chicago. These studies paint a consistent picture: SYEPs have little impact on participants’ long-term job prospects or academic performance but have dramatic impacts on their propensity to commit a crime.

Before investigating the long-run effects, it is worth outlining the short-run impacts: Do SYEPs provide more jobs and higher earnings relative to controls? The evidence says yes. Across three analyses, those who won the SYEP lottery were 54–88 percentage points more likely to have a job during the summer than those who applied but were not admitted (some admitted to the program did not participate, and some not admitted got jobs anyway). Lottery winners also worked more hours, on average. This greater employment led to higher average earnings in the participation year, with estimates ranging from $580 to $876 over the course of the summer. [17] To the extent that SYEPs are meant to directly give young men and women jobs and transfer money to their families, they are successful.

Short-run employment gains do not, however, persist. Admission to an SYEP has a very small (at most, 0.9 percentage points) or no effect on the probability of being employed in the several years following, and appeared, in one study, to lead to net lower earnings, on the order of $100 less per year over three years. Even these small effects tend to fade out, such that by four years after admission, the treatment and control groups are indistinguishable on measures of employment and earnings. [18] In other words, SYEPs do not seem to impart qualities to their participants that make them more employable in the long run.

The story is much the same for measures of the program’s effects on academic outcomes: with a few exceptions, they do little to change participants’ school performance. Participation in an SYEP has essentially no effect on grade-point average, [19] the risk of failing a course in school, [20]or college enrollment rates. [21] It is unclear what effect SYEPs have on graduation and dropout rates. A study of Boston’s program found small positive effects, while studies of New York City’s and Chicago’s programs did not. [22] SYEPs have a small to no effect on days of attendance, with estimates ranging between 0 and 5 days of added schooling among participants, on average. [23] Participants are slightly more likely to take and pass the New York State Regents Exams but with no or a very small overall increase in average scores; [24] there is also no equivalent effect on performance on Massachusetts’s Comprehensive Assessment System. [25]

Summer programs do reduce participants’ risk of committing crimes. That finding holds true across multiple studies and indicators. When comparing those who are not randomly assigned to participate, research has found that SYEP participants are significantly less likely to be arrested, driven by large reductions—30%–45%—in their risk of arrests for violent crime; have significantly fewer (30%–35%) arraignments for property and violent crimes; and have a significant reduction in risk of conviction (31%), particularly of a felony (38%), and of incarceration. [26] The timing, type of offense, and population composition of these effects varied from study to study in ways that are suggestive of the underlying mechanisms. But the topline conclusion is that SYEPs causally reduce crime among participants.

Some evidence suggests that participation in an SYEP extends to other high-risk outcomes. Research on New York City’s SYEP found that it reduced the risk of mortality by 20%, driven primarily by deaths from external causes (such as by accident, suicide, homicide, and drug overdose). [27] Philadelphia’s SYEP had large but imprecisely estimated effects: reducing the receipt of child-protective services (33%) and mental-health and substance-abuse services (31%). And while the programs have few other impacts on academics, Boston’s SYEP even found a 27% reduction in chronic absenteeism. [28]

In summary: SYEPs have limited or no effect on participants’ long-term economic prospects or academic achievement. But they do seem to reduce outcomes linked to high-risk behaviors and situations—most importantly, crime. That effect has been found across several studies, cities, and population sizes, making SYEPs one of the few policy interventions that have proved capable of meaningfully scaling.

How Do SYEPs Reduce Crime?

Much is known about the overall effects of SYEPs; far less is known about how, exactly, they bring about these effects. A study of New York City’s program suggested a three-part typology of how SYEPs might work: providing short-term income, improving labor-market prospects and human capital, and “keeping kids out of trouble,” through “incapacitation” (keeping them busy and off the streets) and through long-term deterrence of high-risk behavior. [29] A study of Chicago’s program suggested that SYEPs could work by improving any of four kinds of capital: financial, human, social, and cultural. [30]

The available evidence suggests a few avenues by which SYEPs affect crime and a few avenues by which they likely do not. SYEPs likely do not work by increasing long-run financial capital/income, or by improving human capital through labor-market or educational experience. There is evidence, albeit mixed, that they work through short-run incapacitation and short-run improvements to earnings. And there is suggestive, though inconclusive, evidence that SYEPs may encourage participants to avoid criminal behavior by increasing their “soft” skills, such as enhanced emotional and social competency. They may also work through other unexplored causal channels, such as by exposing participants to new peers and mentors.

Because SYEPs have negligible effects on educational and workforce outcomes, however, they do not seem to reduce crime through a human capital channel—they do not, in plain English, cause people to commit fewer crimes by leading them to more education, better jobs, or higher earnings. This casts doubt on the claim that SYEPs prove that we should be addressing crime primarily through education and poverty reduction.

In principle, it is possible that the wages that participants earn reduce crime simply by reducing the marginal benefit of theft or other property offenses. SYEP wages are small in absolute terms—on the order of hundreds, not thousands, of dollars—but may be large relative to the annual income of a family at or below the poverty line. The average payment from New York City’s SYEP, $876.26, is about 30% of the monthly income of New Yorkers living at the “extremely low income” band of the city’s measured Area Median Income. [31]

Yet it is unclear whether SYEPs reliably reduce property-crime offending. A study of Boston’s summer program found a 29% reduction in arraignments for property-crime offenses. [32] But several analyses of SYEPs in Chicago and Philadelphia found no effect on rates of property crime, or, in one case, that property crimes increased in the treatment group over three years of follow-up. [33] The Boston study showed that much of the reduction in property-crime arraignments occurred during the program summer, suggesting that if there is a wage-driven effect, it is temporary.

This last point links to a broader question about SYEPs’ potential incapacitation effect: Do they work, in part, by keeping kids off the street during the summer? Crime rates tend to be higher in the summer months, and the individuals targeted by SYEPs—teens to young adults—are relatively more likely to commit crimes than their older or younger peers. SYEPs may control crime simply by putting crime-prone youths in a situation where it is harder to commit offenses that they otherwise would commit.

Whether SYEPs’ effects are incapacitative depends on when participants commit less crime relative to nonparticipants during the program or after. But the research on this issue is inconclusive. Heller found that the reduction in violent-crime arrests in her SYEP group happens entirely post-program; Modestino found a during-program effect for property-crime arraignments but not for violent-crime arraignments; Kessler et al. found large effects on a variety of measures of arrests both during and after the program summer. [34] In short: it is possible that SYEPs have an incapacitation effect, possibly specifically on property-crime offending, but the evidence is equivocal.

SYEPs do not work through human capital benefits, but the durability of their effects suggests that they must work through more long-term channels than incapacitation and remuneration. One explanation is that the experience of work provides a set of skills that do not translate into better academic or labor-market outcomes but that do make participants less likely to engage in violence. SYEPs could impart “soft” social skills that potential offenders lack, thus raising them above a threshold of social competency below which they might be prone to engaging in violence, without making those who already have those skills more employable.

In her study of Boston’s SYEP, Modestino provides suggestive, albeit noncausal, evidence of such an effect. Her treatment group (which saw declines in both property and violent arraignments relative to the control group) also self-reported improvement in social skills—with significant increases since the beginning of the program and, compared with the control group, in the ability to resolve conflicts with their peers and connection to groups or their community. [35] These effects, Modestino and Paulsen found, concentrated among African- American boys, who are at heightened risk of both criminal offending and victimization. [36]

But that evidence was only suggestive, and more information is needed about the provenance and durability of those effects. In Heller’s original study (2014) of Chicago’s SYEP—a sample that was 95% black—half the treatment group received a socio-emotional learning intervention, focused specifically on teaching them to manage adverse thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. There was zero difference between that half ’s propensity to commit a violent crime and the other half of the treatment group.[37] In Heller’s 2021 study of Chicago’s SYEP, meanwhile, the treatment group was again divided between those who merely worked and those who worked and had a mentor and exposure to a civics curriculum. Only the latter group saw a significant reduction in arrest risk, one that was twice as large as the reduction for those who merely got a job. [38]

It is likely that some element of the SYEP, apart from simply having a job, partially determines the programs’ consistent crime-reducing effects. It remains unclear, however, what element that is, and why it works.

There is reasonably strong evidence that SYEPs’ crime-reducing benefits accrue primarily to the teens and young adults most at risk—that SYEPs work, in other words, primarily by shaping the propensity to offend among those individuals already most likely to commit crimes. Kessler et al., using data from New York City’s SYEP, found that the crime reduction was driven by the 3% of program participants with a prior arrest record; the effects on those without a prior record were “a precisely estimated zero.” [39] Modestino showed that reductions in the number of crimes caused by participation in an SYEP were driven entirely by those with at least one post-program arraignment—participation reduces the frequency of arraignment among offenders, although not the probability that someone is ever arraigned. [40] Heller, using a complex statistical method and data from Philadelphia and Chicago, estimated that those most at risk for offending see a much larger effect than those least at risk. [41] However, Davis and Heller, in an earlier paper, found that the most at-risk groups were not significantly more likely to see a reduction in violent-crime arrests. [42]

That SYEPs’ overall effects are possibly driven by reductions in offending among those at risk is surprising, given that these programs mostly do not explicitly target youth at risk of criminal offending—and similar work programs that do target such at-risk youth do not tend to work. As Heller noted, most youth employment programs evaluated as of her first paper (2014) did not reduce criminal offending; and, in some cases, they increased it. SYEPs do not pull a group of at-risk youth together and try to fix them; these programs combine at-risk and not-at-risk peers and reap enormous benefits.

This suggests, in part, that the beneficial effects of SYEPs are driven by a peer or mentor effect—by introducing participants to people whom they would not otherwise meet, thereby altering their network of social relations and personal trajectory. There has not been, to date, an investigation of the role that novel peers may have in reducing crime among SYEP participants. Given the powerful effect that peer groups can have on the propensity to offend, [43] this warrants further investigation.

If the preceding leaves you unsure as to how SYEPs work, you are in good company—there is, put simply, much that isn’t known. This strongly suggests that a high priority for New York and other SYEP administrators should be to better isolate the causal mechanisms that lead to the programs’ crime-reducing effects.

Assessing SYEPs as a Tool to Reduce Crime

Summer youth employment programs result in relatively large reductions in the propensity to offend, as measured across a variety of indicators. Still, in absolute terms, how big of an effect do SYEPs have? How heavily can cities lean on them as a crime-fighting tool, relative to other policies? Most estimates indicate that SYEPs are worth the money, purely in terms of savings from crime reduction. But their overall effects, while significant, are not dramatic, and we should be careful about ascribing too much power to the programs.

All cost-benefit analyses assess SYEPs to be worth the cost in terms of social savings. In general, the programs are estimated to cost about $2,000 per participant (New York’s cost is an estimated $2,200), with roughly 75% going to wages (which are, in most formulations, considered a government transfer and thus net-neutral for purposes of assessing social impact). Heller assessed net savings of Chicago’s program to be $1,700–$1,900, while Modestino (2019) estimated a $1,900 savings in Boston. Kessler et al. estimated savings of between $652 and $1,250, although those accrued entirely to at-risk youth; the savings for non-risk youth is on the order of $2–$3. Essentially, all these benefits come from saving the costs of crimes not committed, although Gelber et al. also estimate large benefits from mortality reduction effects. [44] In short, because they reduce crime and are relatively cheap to administer, SYEPs are worth the money.

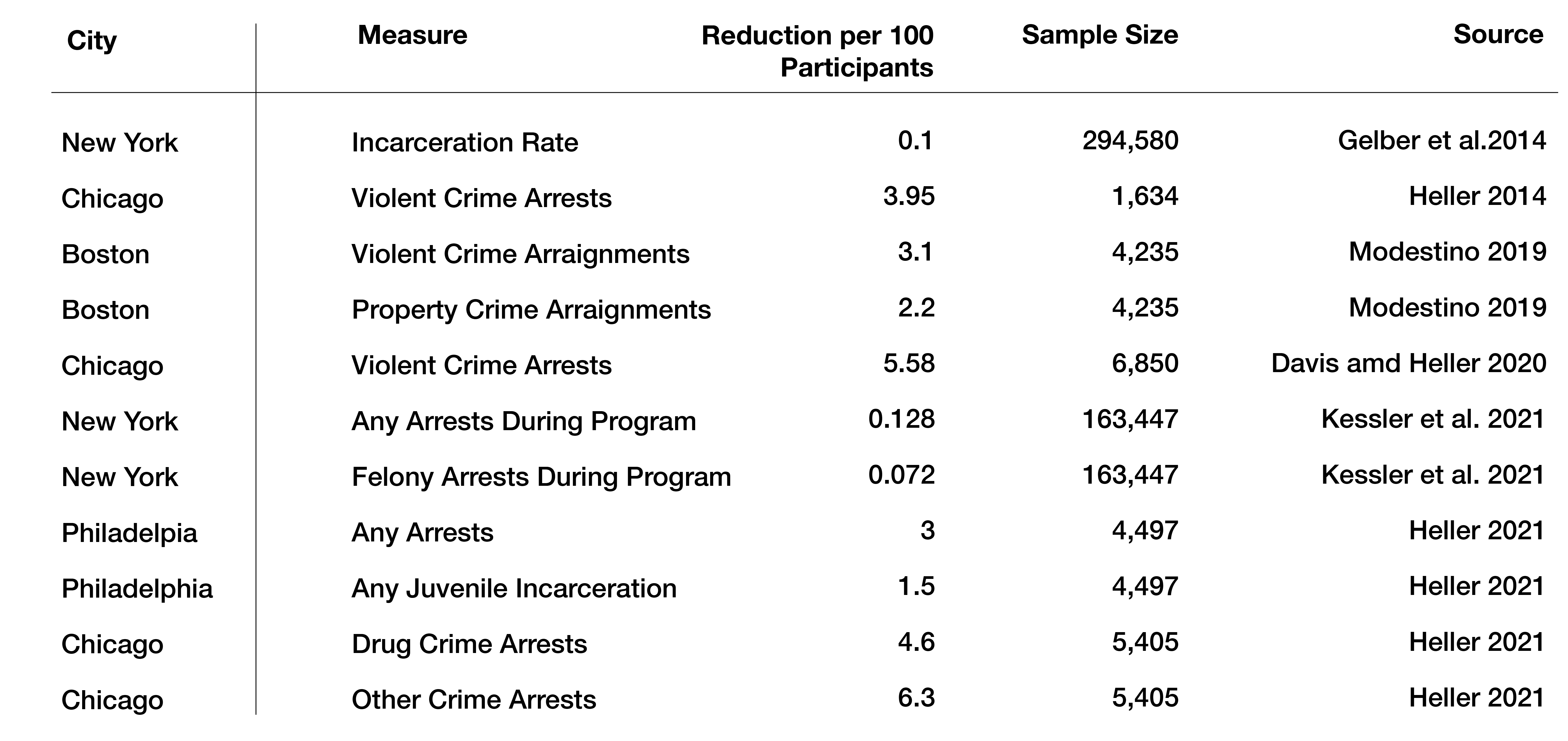

How much bang do cities buy for their buck? Table 1 displays a selection of statistically significant crime-reducing effects from the research base, represented as how many fewer instances of the measure (arrests or arraignments) occurred in the treatment group versus the control group, adjusted per hundred participants—the percentage-point reduction attributable to admission. The overall impression across multiple measures is that SYEP participation reduces criminal offending on the order of one to five percentage points.

Table 1

SYEP Crime Reduction in Four Cities

Notably, the rate estimates scale inversely with the size of the sample: the two studies of New York, with sample sizes on the order of hundreds of thousands, report much smaller per-capita reductions in offending than the smaller studies of Chicago, Philadelphia, and Boston. According to the authors of the New York studies, this is because there is a lower base rate of offending in the control population, which is why the studies report similar percentage-wise, but different rate-wise, reductions. In absolute terms, it implies that the number of crimes prevented by New York’s much larger program was within the same order of magnitude as the number of crimes prevented by the other, smaller programs.

These results may mean that there is a small, and fixed, population of potential offenders within the broader SYEP-eligible population. As the number of enrollees grows, it becomes harder for the program to “find” potential offenders to add to its roster (assuming that selection for the program is not random, regarding the potential to offend). This is consonant with the observation that criminal offending is a highly concentrated phenomenon, with small groups of serial offenders accounting for a large share of offending. [45] But it implies that from a crime-reduction perspective, a larger program is not necessarily more efficient than a smaller one, as there may be diminishing marginal returns to scale.

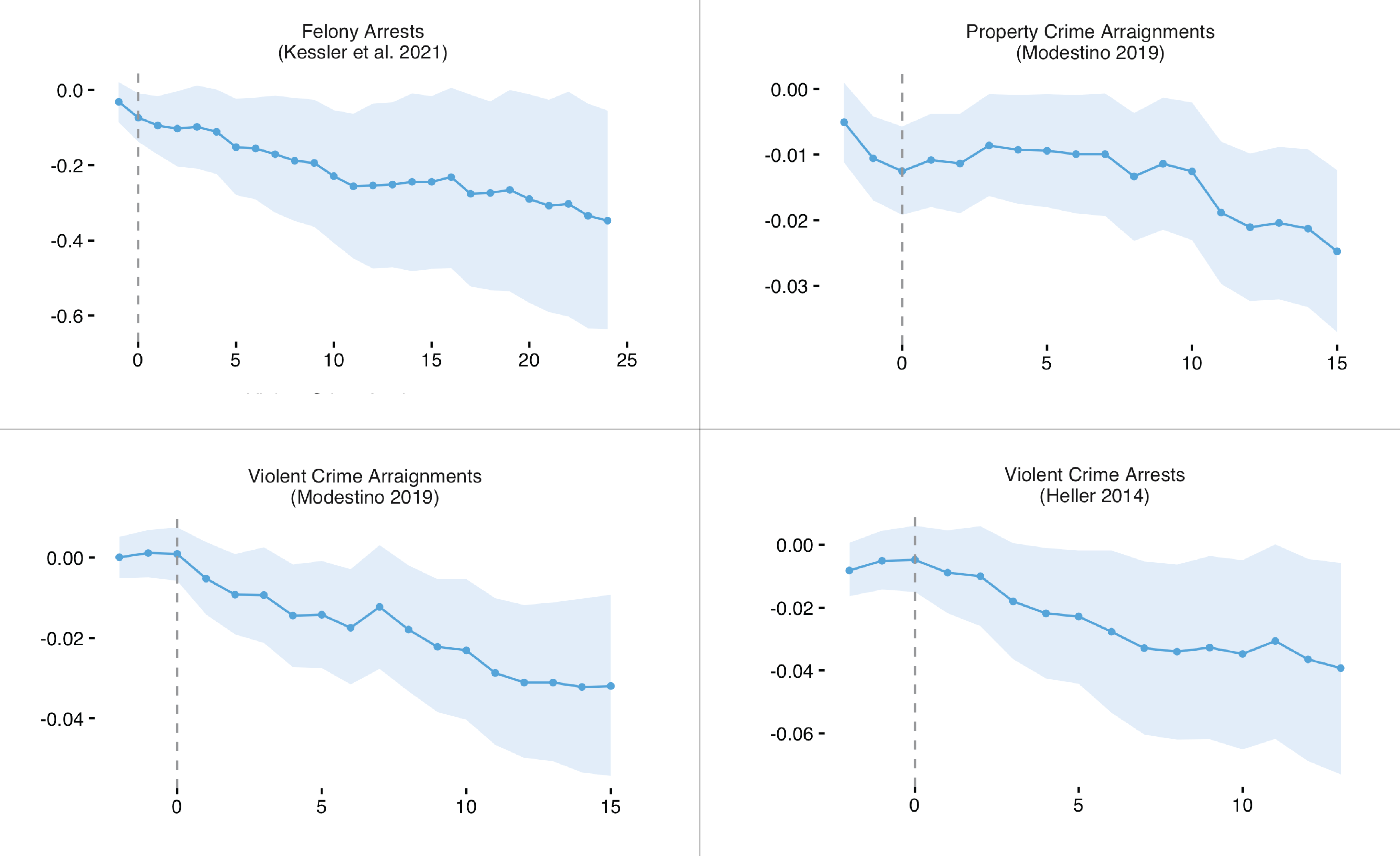

There is another limit on SYEPs’ efficacy worth highlighting. Like many other policy interventions, the crime-reducing effects of SYEPs appear to fade over time. As one can see in Figure 2, the slope tends to decrease around one year out. Davis and Heller found that there was no difference between treatment and control groups’ propensity to offend by the second year post-program; Kessler et al. found that the bulk of the effects on offending happened during the program summer itself. Valentine et al. in an assessment of New York’s SYEP’s work effects, found small improvements in the probability of participants finding employment, but these also faded out by the third year post-program. [46]

Figure 2

SYEP Participation and Crime over Time

Months After Program Ended

Modestino and Paulsen found in their study of Boston’s SYEP that the program’s effect on chronic absenteeism—reducing it by 27% among those admitted to the program—persists more strongly when participants are admitted to a second summer in the program. [47] It is not clear from this limited example, however, what the “dose-response” ratio is more generally, or on crime outcomes in particular: in other words, it is not known if more than one summer in the program reduces crime post-participation more strongly than a single summer.

A Great Experiment: Recommendations for New York City’s SYEP

New York City’s SYEP is the leader in a field that has attracted increased interest as policymakers look for nonpunitive approaches to reducing crime. New York’s new mayor should see next summer not only as an opportunity to restore his city’s summer jobs program to full capacity but to take the lead in maximizing its potential here and in SYEPs nationwide. That would be a boon for the research of other cities—Philadelphia, Chicago, Boston, and beyond—which, in turn, informs New York’s program.

First, the city’s leaders should not insist that its summer jobs program improves academic or job-market performance—it does not. Instead, the research suggests that leaders should see the SYEP primarily as a tool for reducing crime and, more generally, antisocial/harmful behaviors.

It is possible that SYEPs could be retooled to improve academic and labor-market outcomes. But any dramatic change risks limiting the program’s effect on criminal behavior. Other programs may be more appropriate to boost young people’s academic and job-market prospects. Summer school, for example, may have small effects on academic performance for at least some participants, and vocational education programs may improve the probability of employment. [48]

Second, the city ought to dedicate serious time, energy, and resources to better understand why SYEPs reduce crime. As home to the nation’s largest and best-funded program, New York is uniquely well positioned to oversee research in this area that will benefit not just New Yorkers but Americans in cities across the nation. Such research would allow cities to administer their SYEPs more efficiently, from the perspective of improving citizens’ lives as well as maximizing the effect per dollar. New York should allow researchers (particularly those mentioned in this brief) to coordinate with the Department of Youth and Community Development to design research in advance of next summer’s program.

Three questions are obvious candidates for more research. First: How much of SYEPs’ effects on criminal behavior are driven by the actual jobs they provide, versus other parts of the program, such as the training for work readiness, teamwork and conflict resolution, and financial literacy education—and how can the crime-reducing benefits of each be maximized? Second: What share of SYEPs effects are driven specifically by at-risk participants, and how can returns on their participation be maximized? Third: How can SYEPs be optimally timed, including beyond the summer?

On the first question: the evidence remains ambiguous as to what feature or features of SYEPs are actually causing participants to be less prone to offend. Is it simply having a job, or is it the training and mentorship that comes with having a job? In either case, what, if any, competencies or attitudes does participation impart? Modestino (2019) suggested that improvements to conflict resolution skills and improved respect for the community may be at play. Heller et al., in a non-SYEP study, [49] found surprisingly strong crime-reducing effects of a program focused on at-risk youth, which, she and her coauthors argue, is driven by an improvement in impulse control; could SYEPs improve this faculty?

Some of these questions are easier to investigate experimentally than others. Systematically assigning some participants to non-job interventions—mentorship, training, cognitive behavioral therapy—and comparing outcomes would add to the evidence base on the role played by work versus nonwork components of SYEPs. Assessing the causal impact of different attitudes or skills on subsequent offense risk is harder, but suggestive evidence could be produced by administering pre and post-program surveys to participants and nonparticipants, to see if findings such as those of Heller and Modestino hold up.

On the second question: there is moderate evidence that the effects of SYEPs are concentrated among the small share of participants who are at risk of criminal offending when they enter the program. If this is the case, limiting admission to eligible young adults who are demonstrably at risk of criminal offending, such as those who already have a criminal record, could have a dramatic impact on crime. But there are reasons to be skeptical: other programs that target only at-risk youth tend to have little effect on the propensity to offend. Further, if some proportion of SYEPs’ effects on crime arises from peer influence, excluding participants who are not at risk could boomerang, inducing more crime as harmful social networks form. To determine if there is an “optimal” share of at-risk offenders, the city could, post-assignment, randomize participants to workplaces with a greater or smaller share of at-risk coworkers. By following up on the effect of exposure to future offending, the city could learn more about peer effects in SYEPs, as well as about how much the program could be targeted primarily to potential offenders without losing efficacy.

On the third question: it remains unclear as to whether SYEPs’ effects on crime primarily accrue during or after participation in the program. If the former, then a longer program might be preferable. The effect of repetition on SYEP fadeout has been discussed; should program administrators make a deliberate effort to encourage several summers of participation—and, if so, how many? As a candidate, Eric Adams proposed making the SYEP a year-round offering. [50] Would this render the same crime-reducing results, or is there something unique about summer, when kids are out of school and crime is more common, that matters? New York can investigate all these questions.

New York City has been a leader in proving that SYEPs work: they often produce significant reductions in crime. If the city’s leadership is genuinely dedicated to effective anticrime interventions, they should also take the lead in finding out how to make SYEPs work better—how to wring more benefits for participants with fewer costs, in a way that cities across the nation can learn from.

About the Author

Charles Fain Lehman is a fellow at the Manhattan Institute, working primarily on the Policing and Public Safety Initiative, and a contributing editor of City Journal. He was previously a staff writer with the Washington Free Beacon, where he covered domestic policy from a data-driven perspective. His work on criminal justice, immigration, and social issues has appeared in the Wall Street Journal, National Review Online, and Tablet, among other publications, and he is a contributing writer with the Institute for Family Studies. Lehman holds a B.A. in history from Yale University.

Endnotes

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).