Catholic School Enrollment Boomed During Covid. Let’s Make It More Than a One-Time Bump

Introduction

The National Catholic Educational Association (NCEA) has collected diocese-level data that provides important information about Catholic school enrollment trends dating back to 1920. The story these data have told has been a simple one: the rise of Catholic education for many years, its peak in the 1960s, and then, with a few exceptions, its decades-long decline.[1] This year’s data, however—coming on the heels of a once-in-a-generation shift in parental demand for school choice—may be the start of something different.

The 2022 NCEA data provide an invaluable window into how the landscape of American education has shifted over the past two years in response to Covid-19-related school disruption. Between 2020 and 2022—a period marred not only by the health and safety worries that Covid brought but also by the heated debates about how schools should serve students amid a pandemic—Catholic schools stood apart for their agility in an uncertain environment and their leadership in putting students first.

In early spring 2020, many Catholic schools were the first to close, responding quickly to the threat that was still not fully understood.[2] Then in fall 2020, Catholic schools, far more so than either public or charter schools, stood apart again by finding a way to reopen safely for in-person learning.[3]

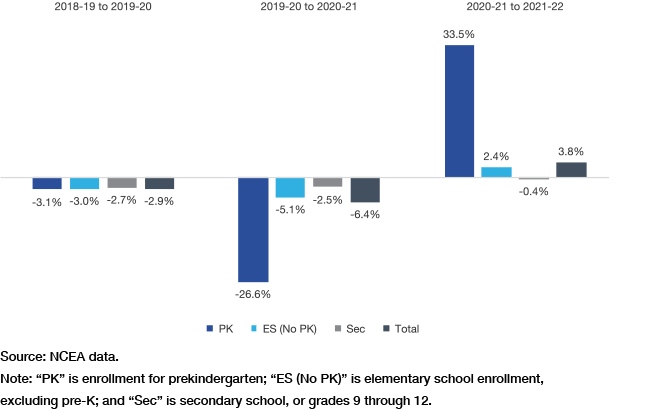

No doubt buoyed by the work Catholic teachers and leaders did to center the urgent educational needs of children in their response to the pandemic, the 2022 NCEA enrollment results reveal a historic 3.8% nationwide enrollment increase for all Catholic elementary and secondary schools—“the first increase in two decades and the largest recorded increase by NCEA.”[4]

This increase (Figure 1) is remarkable not only because it is the first nationwide Catholic school enrollment increase in 25 years[5] but also because public schools around the country are reporting significant enrollment declines in both years of the pandemic.[6] Indeed, recent public-school enrollment analyses reveal not only that public-school enrollment between 2020 and 2022 cratered but that the longer districts remained in remote or hybrid learning, the more dramatic their enrollment declines.[7]

Figure 1

Catholic School (Pre-K through 8th Grade) Enrollment in Recent Years

Even more heartening for long-embattled Catholic school supporters, the 2022 enrollment increase comes on the heels of what was, in 2021, the “largest single-year decline in the 50 years NCEA has collected data.”[8] Indeed, if Covid had never happened, and if Catholic school enrollment followed the same rate of decline it experienced in the years prior to the pandemic, we estimate that there would be tens of thousands fewer students enrolled in American Catholic schools today (Figure 2).[9] That is to say, while the 2021 decline was sharp, the 2022 rebound may well represent not just a one-time bump but an important and enduring shift in Catholic school enrollment.

Figure 2

Projected vs. Actual Catholic School Enrollment

In order to understand whether the 2022 rebound represents a true reversal of the previous decline in Catholic school enrollment, it’s important to dive deeper to understand where the increases were concentrated and what we can learn from them.

To that end, analyzing the numbers by grade level provides some insight into just what may have changed and where. Pre-K, for instance, accounts for 40% (or 44,584 students) of the 2021 enrollment decline and 66% (41,190 students) of the 2022 rebound.[10]

K-8 Catholic school enrollment, by contrast, rose by 2.4% (23,100 students) between 2021 and 2022, and secondary school enrollment saw a modest 0.4% (2,164 students) decline from 2021 to 2022.[11] These numbers (Figure 3) provide a glimmer of real hope for the future of the Catholic school sector, because it suggests that the parents who are driving the 2022 enrollment increase are those making school decisions for their children for the first time—and those who will be driving the trends for the next generation of students.

Figure 3

Percent Change in Catholic School Enrollment Over Time

Comparison of Catholic School Enrollment, by Region

The 6.4% nationwide enrollment decline that Catholic schools experienced from 2019–20 to 2020–21 was driven at least in part by a pandemic-induced wave of Catholic school closures.[12] Immediately prior to the start of the 2020–21 school year, and no doubt accelerated by the pandemic, 209 Catholic schools closed or merged. This was the largest wave of Catholic school closures since 2006.[13]

Those closures were concentrated in two regions: New England, which shuttered 32 schools (8.9% of its total schools), and the Mideast, which closed 99 schools (7.6% of its total schools).[14]

Fortunately, all six regions, including New England and the Mideast, experienced an enrollment rebound in 2021–22. Two of the six regions—the Plains and the Southeast—saw increases that nearly made up for their initial 2020–21 decline (Figure 4). Specifically, the Plains saw a 3.8% enrollment decline in the 2020–21 school year and a corresponding 3.8% increase in 2021–22, bringing overall enrollment in the region to within 0.1% of its 2019–20 number. Similarly, enrollment in the Southeast dropped by 4.9% in 2020–21 and increased by 4.7% in 2021–22, rebounding the region’s overall enrollment to within 0.4% of pre-pandemic 2019–20 enrollment levels.[15]

New England also saw a 2021–22 rebound that nearly made up for the 2020–21 losses. Enrollment declined in the region by 6.4% in the 2020–21 school year (in the same time frame, the region lost 10% of its schools), but then enrollment bounced back in 2021–22 by 5.6%, bringing overall enrollment to within 1,053 students of its 2020 number.

Figure 4

Catholic School Enrollment Drop and Rebound, by Region

In contrast, the Mideast region—which includes Pennsylvania, New York, New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, and Washington, D.C.—suffered the most significant losses of any region over the course of the pandemic. In 2021, the Mideast region closed 99 schools overall (7.6% of the total number of schools) and saw enrollment declines of 8%. Worse, the 2022 rebound in the Mideast was the smallest in the nation, with Mideast dioceses experiencing just a 2.1% enrollment increase between the 2020–21 and 2021–22 school years.[16]

Even more troubling about the Mideast trends is the fact that, historically, school closures seem to accelerate enrollment losses rather than stabilize systems. A deeper dive into what happened in six large dioceses (Philadelphia, New York, Brooklyn, Chicago, Buffalo, and Camden) in the three years preceding and the five years following large-scale school closures reveals that no diocese was able to stabilize or rebuild enrollment after the closures.[17] Indeed, in each of the six dioceses, enrollment declines continued year after year.

Moreover, recent guidance from the Vatican has underscored the point that school closures—particularly closures that are aimed at leveraging Catholic school buildings for revenue—should be avoided. Specifically, the Vatican warns that “the closure or change of the legal structure of a Catholic school due to management difficulties … should not be solved in the first instance by considering the financial value of buildings and property with a view to selling them, or by transferring management to bodies that are distant from the principles of Catholic education in order to create a source of financial profit.”[18] This definition would include, for example, closing Catholic schools and renting the space to charter-school operators. Rather, the document goes on to explain, “the temporal goods of the Church have among their proper purposes works of the apostolate and charity, especially at the service of the poor.”[19]

To be sure, it is understandable that diocesan leaders, particularly in large urban dioceses that have seen the most dramatic demographic shifts over the past two decades, have worked to “rightsize” the number of parishes and schools needed to serve the communities as they now exist. At the same time, diocesan leaders must acknowledge that school closures risk making the entire system weaker if they are not paired with intentional and systemic changes aimed at improving schools and attracting and retaining more students. Reinvigorating Catholic education, rather than managing its decline, is what’s needed to ensure a thriving Catholic school sector that serves students of all socioeconomic levels.

State-by-State Enrollment Trends

Just as Covid has impacted regions differently, there is also wide variability in one-year and two-year enrollment trends across states (Figure 5). Just six states—Idaho, New Hampshire, Nevada, North Dakota, South Carolina, and Colorado—saw Catholic school enrollment increases in both 2020–21 and 2021–22, but an additional 14 states saw a 2021–22 enrollment rebound that was large enough to make up for the initial 2020–21 decline. Taken together, that means nearly half of all states (20) have as many or more students today than before the pandemic began.[20]

Figure 5

Pre-K through 12th Grade Catholic School Enrollment from 2019–20 to 2021–22, by State

In the 10 states with the largest Catholic school enrollment, which account for 59% of total enrollment nationwide, enrollment declined in 2020–21, then rebounded in 2021–22. However, the size of the 2021–22 rebound varied dramatically (Table 1).

Florida, for instance, had the largest overall increase in enrollment (6.3%) between 2020–21 and 2021–22, boosting Catholic school enrollment in the Sunshine State to near prepandemic levels. California had the second-highest 2021–22 enrollment rebound (5.2%), recapturing about half of the enrollment that was lost in the 2020–21 school year.

New Jersey also experienced strong 2021–22 enrollment gains, increasing by nearly 4%, but that rebound was not nearly enough to account for the 10.4% decline the state’s Catholic schools experienced in 2020–21, leaving the state with an overall two-year decline of 7.0%.

Table 1

Percent Change in Catholic School Enrollment over Time in Select States

New York State, whose overall enrollment dipped by nearly 9% in the 2020–21 school year, experienced only a very modest increase (0.8%) in 2021–22. That slight rebound wasn’t nearly enough to make up for the 2020–21 loss and left the Empire State with a two-year enrollment decline of 8.2%—the second largest (behind only Wyoming, which lost 24% of its 740 students between the 2019–20 and 2021–22 school years) in the nation.

Public-School Covid-Mitigation Policy and Catholic School Enrollment

The historic 2021–22 increase in Catholic school enrollment takes place against the backdrop of intense public debate over Covid mitigation and related school-closure and remote-learning policies. While virtually all schools shifted from in-person to remote learning in March 2020, it was Catholic school leaders who led the way on school reopening in September 2020. Indeed, while just 43% of public schools and 34% of charter schools offered in-person learning in September 2020,[21] fully 92% of Catholic schools offered in-person learning.[22] Many school districts that struggled to reopen on the first day of the 2020–21 school year remained online or used only hybrid learning for the bulk of the year, some not fully reopening until fall 2021.

This fueled intense frustration among many parents, who appeared to vote with their feet by moving their students into the schools that had stayed open throughout the 2020–21 school year: local Catholic schools.

One of the most common patterns in public opinion polling on education involves parents who give low grades to American education in general but high marks to their local public schools. Yet, the inability of public schools to adapt to the demands of in-person learning during Covid seems to have fractured the once steadfast relationship between parents and their local publicschool district. Indeed, enrollment data from 2020–21 revealed that public-school enrollment dropped 3% overall, with some cities, like New York, reporting record numbers of students escaping into nontraditional education options.[23]

The public-school numbers for pre-K are even starker, with pre-K enrollment dropping to the lowest levels seen in 25 years. In October 2021, Education Week reported U.S. Census data that showed “only 40 percent of 3- and 4-year-olds enrolled in school in 2020, a 14 percentage-point drop from 2019 and the first time since 1996 that fewer than half of U.S. children in that age group attended preschool.”[24] In the normally steady world of school enrollment, these kinds of shifts are the educational equivalent of an earthquake.

Perhaps nowhere was the controversy over public-school Covid-mitigation policy and school reopening louder than in Virginia, where parents of students in Loudoun, Fairfax, and Arlington County public schools made headlines as they pushed back against state and local school closure policies.[25] Public-school districts in Northern Virginia were among the last in the nation to open for full-time, in-person instruction. Indeed, some analyses showed that as late as February 2021, fewer than one-third of students in Virginia were attending school in person, and by summer 2021, as many as 40% of public-school students in Northern Virginia were still relegated to remote or hybrid learning.[26]

Given that Virginia kept public schools closed longer than the vast majority of other states in the nation, it’s hardly surprising that the state experienced one of the nation’s largest increases in Catholic school enrollment.[27] Parents truly were voting with their feet in choosing a different educational environment for their children.

The evidence suggests that Virginia Catholic schools—all of which were open for in-person learning throughout the 2021 school reopening debate—were poised to take advantage of this once-in-a-generation opportunity to rebuild support for local Catholic schools. After experiencing a slight dip (–1.8%), enrollment across the state soared by 8.8% in 2021–22. The lion’s share of those Catholic school enrollment increases were concentrated in the Diocese of Arlington (Table 2), which includes the cities and counties that were at the epicenter of much of the school reopening and Covid-mitigation debates in 2021.

Table 2

Comparing Enrollment in Arlington Diocese Schools with Local Public Schools

Even more interesting, unlike other states that saw only negligible (if any) increases in K–8 or secondary schools, Virginia’s overall increase reflected not only a 32% increase in pre-K but also a 7% increase in both K–8 and secondary schools (Table 3).[28]

Table 3

Percent Change in Catholic School Enrollment in Virginia, Compared with All States

This strong increase in Catholic school enrollment is juxtaposed against a 3.5% drop in 2020–21 public-school enrollment that saw virtually no rebound in 2021–22 (Figure 6). Specifically, Virginia public-school enrollment increased by just 320 total students between 2020–21 and 2021–22, compared with an increase of 2,208 students in Catholic schools, bringing the state’s total Catholic school enrollment to 27,269.[29]

Figure 6

Change in School Enrollment in Virginia, by Type

Further south, Florida experienced strong growth in both the Catholic and charter-school sectors (Figure 7). In the Sunshine State, public-school enrollment did not rebound in 2021–22 (increasing less than 1%), compared with a 6.3% increase in Catholic schools and a 5.9% increase in charter schools.

Figure 7

Change in School Enrollment in Florida, by Type

A comparison of public-, charter-, and Catholic-school enrollment trends in additional key states reveals overall pre-K-through-12 enrollment has declined, but Catholic school enrollment is either increasing or stable. For instance, in Illinois, overall pre-K-through-12 enrollment dropped in both charter and traditional public schools for two school years running from 2019–20 to 2021–22, but Illinois Catholic schools saw a strong 2021–22 rebound, increasing enrollment by 3.5% overall (Figure 8).

Figure 8

Change in School Enrollment in Illinois, by Type

Similarly, Louisiana public-school enrollment (Figure 9) declined in both the 2020–21 and 2021–22 school years but saw enrollment increases in both the Catholic and charter-school sector. As this analysis is focused on select states for which public 2021–22 enrollment data was available at the time of writing (winter 2022), it remains to be seen how many states will see similar trends in which Catholic school enrollment outperforms public and/or charter schools.

Figure 9

Change in School Enrollment in Louisiana, by Type

Catholic School Enrollment and School-Choice Programs

Finally, comparing the 2021–22 Catholic school enrollment boost in states that have robust school-choice programs with those that have either no choice programs or limited choice suggests a possible connection between school-choice policy and Catholic school enrollment.

Catholic schools in states that have school-choice programs[30]—vouchers, tax credits, or Education Savings Accounts (ESAs)—had greater enrollment stability over the past two years than Catholic schools in states with no private-school choice (Figure 10). That is, Catholic schools in states with multiple choice programs (two or more) lost far fewer students in the first year of the pandemic (–4.9%) than states with no private-school-choice programs (–7.6%), but both the robust choice and the nonchoice states rebounded in 2021–22 by the same percentage (+4%).

Figure 10

Five-Year Changes in Enrollment by School-Choice Programs

Looking more deeply at the data, the six states that have ESAs saw enrollment increases that were twice as large (6.3%) as in states with no ESAs (3.6%).[31]

The bottom line: when parents have more control over the money spent on their children’s education, they use it to opt into Catholic schools.

Conclusion and Recommendations

The 2021–22 Catholic school enrollment rebound was welcome news for a weary sector—and it was no doubt in part a reward for the important role Catholic schools played in supporting students and communities with in-person options throughout the pandemic. It may also be a signal of just how significantly Covid-induced school shutdowns have driven parental demand for school choice, and it could be a harbinger of things to come.

However, it would be a mistake to draw a trendline from just two years of data. While Covid proved to be an earthquake for American pre-K-through-12 education, inertia could set in and draw parents back into old patterns of schooling. Whether earned or not, that could mean that public-school enrollments will stabilize and rebound.

For Catholic school supporters, however, it’s a reminder that if we want to turn the 2021–22 rebound into an enduring, system-wide enrollment shift, we must seize the window of opportunity we have been given by doing more to maintain these gains. In particular, we suggest four things:

First, Catholic school leaders—at the independent network, diocesan, and school level—need to recognize the very real opportunity they have to drive change. For too long, those of us in the Catholic school movement have lamented the challenges we face—the financial constraints we operate within, the increased competition we face from charter schools, the lack of access to state and federal funding, and more—and accepted our fate as something that happens to us rather than as something we control. The challenges Catholic schools face are real, and in some places, they present an existential threat. But the presence of threats and challenges should make us even more committed to taking advantage of this moment to reconsider old ways of doing things and drive lasting change.

When it comes to enrollment, for instance, we often erect our own barriers to entry that make growth and sustainability more challenging. Catholic school admissions processes are often so onerous that parents opt out early in the process. Scholarship paperwork can be cumbersome that families facing crises—who are often exactly the families we want to attract and serve—are simply unable to meet the demands of registration. Similarly, tuition policies and procedures are so opaque that interested parents bow out before they even begin an inquiry.

These barriers are within our control to change; removing or streamlining them can have a real, immediate, and measurable impact on school enrollment.

Second, Catholic schools and dioceses that experienced a 2021–22 enrollment bump should acknowledge how vulnerable they are right now to a 2022–23 enrollment decline. The reality is that when it comes to reenrollment, the most difficult students to retain are those who have most recently joined the school community. This makes sense, given that the longer a student has attended a school, the stronger the connection to the community will be. But it also means that a significant one-year bump can be difficult to translate into enduring change. School leaders looking to grow their communities should focus as intensively on retaining newly enrolled families as they do on attracting new students.

Related to this is the fact that the lion’s share of the recent enrollment increase was concentrated in pre-K. In the transition from pre-K to kindergarten, it is common for parents to shop around and explore new options. And given that many parents pay for childcare or pre-K, but fewer pay out of pocket for kindergarten, the chances of Catholic schools losing new families to free public and charter options is high. Now is the time to focus on retaining students from pre-K as well as attracting as many new kindergarten students as possible. In fact, in schools that are typically one classroom per grade, leaders should consider the possibility of adding a second kindergarten class, even if they cannot sustain that class through 8th grade, because it will help build a solid enrollment base that will yield dividends for years to come.

Third, Catholic school supporters and diocesan leaders need to think differently about urban Catholic school management and governance. Too many parishes are stretched thin—often to the breaking point—and schools can be among the most complex of the church’s ministries. It’s time for dioceses to consider new governance models that delegate autonomy, management, and oversight to lay leaders in exchange for accountability for results. Models like the Independence Mission Schools, the Cristo Rey Network, and Partnership Schools show how a combination of autonomy, lay leadership, and Church oversight can bring together the best of Catholic governance with the innovation that struggling schools need to thrive.[32]

Finally, it is well past time for public officials to recognize the value that Catholic schools bring to traditionally underserved communities and to consider the possibility that these schools are facing long odds for survival. The Supreme Court cleared many of the presumed legal obstacles to public support of religious schools in the 2020 case Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue,[33] and it may clarify the issue further in the pending Carson v. Makin decision, which focuses on the issue of whether or not a state may restrict a student’s access to state-sponsored financial assistance when the student would use it for a private religious school.[34] It is time for Catholics to demand that our governors and state officials recognize religious freedom and the rights of parents to choose schools aligned with their priorities and to support providing public funds to exercise those rights.

Catholic schools responded proactively and productively to the Covid-19 pandemic, and parents rewarded them by enrolling their children. To maintain the trust of those parents and families, Catholic school leaders can’t simply assume this enrollment bump will continue without reform and creative thinking.

Endnotes

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).