Editor's note: The following is the fifth chapter of Urban Policy 2018 published by the Manhattan Institute.

Introduction

At the Copake Iron Works Historic Site in upstate New York, a plaque carries an enduring lesson about what is now called affordable housing: “[T]his building is a two-family dwelling.… Multiple-family dwellings were less expensive to build and heat. In an era before the automobile, having employee housing near the work place was important to assure a reliable and available work force.”1

Today, the goal of encouraging affordable housing near jobs is more relevant than ever—especially for those parts of the U.S., such as Silicon Valley, where the economy is strong, inexpensive housing is scarce, commutes are long, and employers worry about their long-term ability to attract the workforce that they need. “We need homes that working families can afford,”2 says Carl Guardino, CEO of the Silicon Valley Leadership Group, which comprises nearly 400 area business leaders concerned about their firms’ ability to attract and retain workers of all types.

Reducing the cost of housing in expensive regions requires a large increase in supply. But in most cities, regulations limit new construction to peripheral sprawl and downtown high-rises. In the Bay Area, even the exurbs are largely off limits, leaving only pockets of high-rise construction as an inadequate release valve for pressure on the housing market. This paper explores an approach inspired by the time before World War II, when major U.S. cities, small industrial towns such as Copake, and rich suburbs alike provided a “housing ladder”—a spectrum of housing affordable to all types of buyers and renters that facilitated upward mobility and reduced energy consumption.

In today’s context, several forms of “missing-middle” housing (two- to nine-unit family structures) could be built even in areas generally hostile to development, like Silicon Valley. Potential options include “infill” construction along neighborhood commercial corridors, “greenfield” construction on vacant land, and “brownfield” construction alongside office parks and other industrial space. As ride-sharing, driverless cars, and other alternative forms of transportation develop, properly sited missing-middle housing may reduce automobile commuting, too.

The Challenge of High Housing Costs

Housing costs in some of America’s most economically dynamic metropolitan areas are very high. Nowhere are they higher than in the Bay Area. By one estimate, the household income needed to afford a median-priced home in metropolitan San Jose ($216,181) or San Francisco ($171,330) is the highest in the country. San Jose requires twice the income needed in other prosperous U.S. metropolitan areas, such as New York ($99,151) and Boston ($97,465), and it requires almost four times the income needed in Dallas ($59,517).3Another survey computed the ratio of metropolitan San Jose’s median house price to median household income as a “severely unaffordable” 9.6, the highest in the U.S. and more than three times the survey’s threshold of 3.0 for deeming a market “affordable.”4

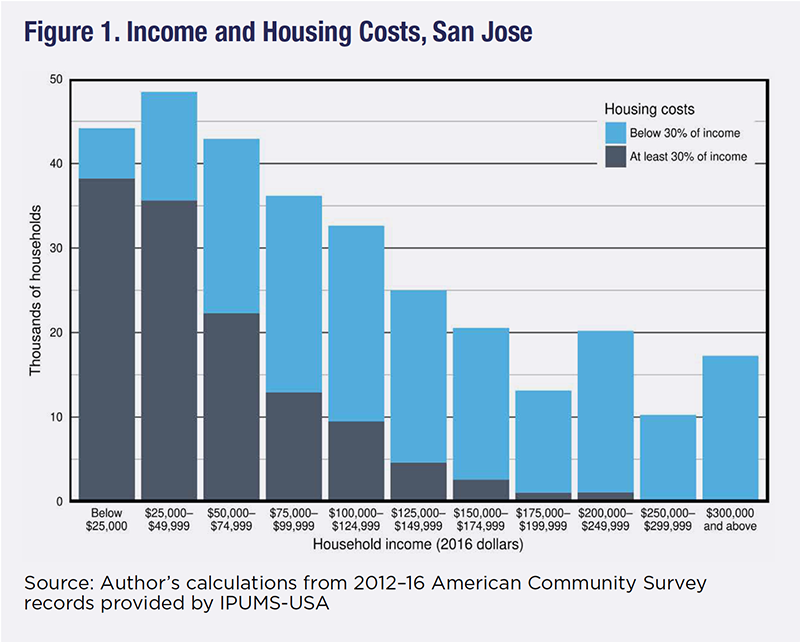

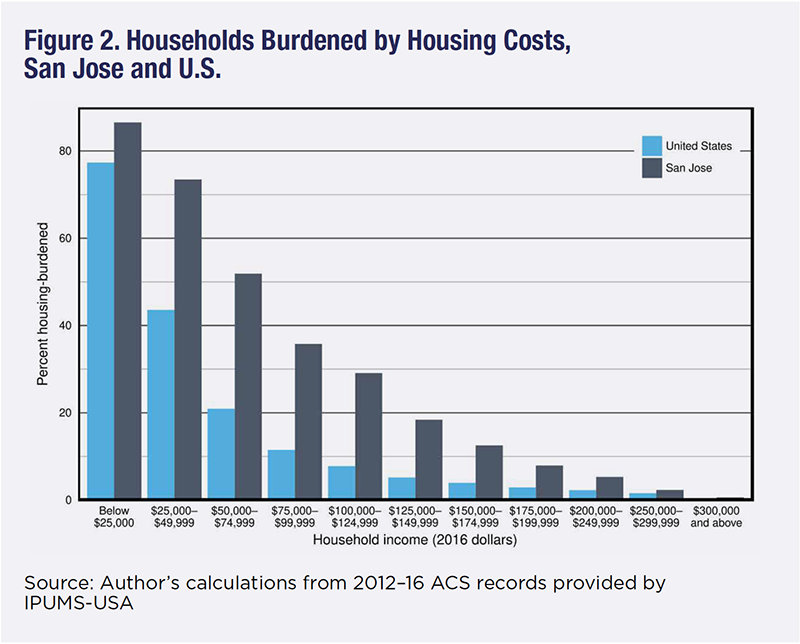

San Jose’s high housing costs discourage working- and middle-class families from moving there (Figure 1). A majority (57.4%) of the city’s households earn at least $75,000 per year, the highest income bracket for which the Census Bureau tabulates housing costs, compared with only 37% percent for the U.S. as a whole (Figure2).5 San Jose’s housing costs even burden the professional classes: 18.7% of the city’s households making over $75,000 pay more than 30% of their income in housing costs,6 the threshold at which most rental-housing programs consider a household to be “housing-burdened.”7 This compares unfavorably with, say, Boston (where 12.6% of households making more than $75,000 are burdened), Chicago (8.1%), Austin (5.7%), and Charlotte (4.1%).8

Figures 1–2 actually understate the housing burden on San Jose’s upper middle class, as they average very wealthy households together with households that earn about, or less than, the city median ($101,000). In fact, the survey records underlying the Census Bureau’s computations show that San Jose households earning $100,000–$125,000 are more likely to be housing-burdened than households nationally earning $50,000–$75,000. In San Jose, even relatively high salaries may not help employers attract the talent that they need.

High housing costs have broad effects well beyond specific industries or areas. Notes William Fischel of Dartmouth College: “It appears that the rise of land use regulation in the 1970s has reduced migration from low-income regions of the United States to higher-income regions. This seems to have contributed to the rise in income inequality in the last 40 ;years.”9 Enrico Moretti of the University of California at Berkeley and Per Thulen of the KTH Royal Institute of Technology (Sweden) find that every job in high technology adds five jobs in “non-traded” sectors, such as personal services.10 By encouraging labor mobility, more affordable housing in Silicon Valley would have widespread benefits elsewhere in California and across the U.S.

Plans for New Housing

California officials have long recognized that a housing shortage threatens the state’s economic health. The state government has responded by requiring localities to meet quotas (“regional housing needs”). For example, the state requires Santa Clara County, in which San Jose is the largest city, to permit 58,000 new housing units by 2023. San Jose has set its own goal of 25,000 new units,11 an 8% increase over the 328,000 that already exist.12 As of April 2017, however, Santa Clara County municipalities had issued only 16% of the required permits.13

Though California mandates a total number of new units, it does not mandate what housing forms to build, and for good reason: zoning rules have historically been the purview of local authorities. Yet in other ways, the state has encouraged transit-oriented development (TOD): dense housing within walking distance of mass transit.

Specifically, legislation requires state transportation authorities to incorporate a measure called “vehicle miles traveled” into reviews of new development under the California Environmental Quality Act. This requirement aims to discourage automobile commuting by encouraging high-rise construction near mass transit. (Just 15 high-rise towers of 1,000 units each would meet much of San Jose’s new housing goal.) A proposed state law, rejected in committee in April 2018, would have gone further by precluding low-density zoning near transit corridors. Under that law, downtown San Jose and some commercial thoroughfares would have seen height limits raised to 85 feet (though most of the city’s buildings would have remained single-family).

The environmental motivations for TOD are especially strong in California. Yet other motivations are important. Concentrated high-rise developments appeal, for instance, to thrifty city officials, who can provide public services more cheaply to a dense population, as well as to residents of single-family areas who want to keep their neighborhoods unchanged.

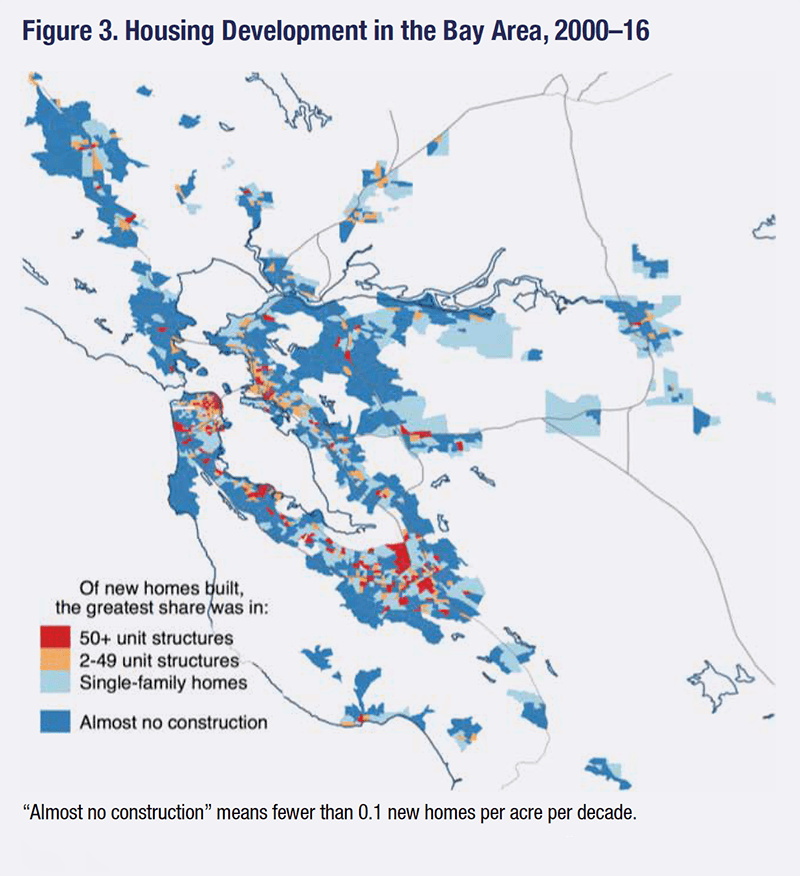

The development that California’s policies encourage is merely an intensified version of the pattern already predominant throughout the United States. Issi Romem of the University of California at Berkeley calls it “pockets of dense construction in a dormant suburban interior.”14 During 1940–60, most American cities saw a single-family housing boom, though some of these single-family areas were later densified with middle-density buildings. Since 1980, however, land-use regulations have halted further densification except in downtown pockets and in the exurbs (less populated commuter towns located beyond denser suburbs); but in the Bay Area, zoning is so restrictive that little construction is happening in the exurbs (Figure 3).

Housing development in the U.S. before World War II offered sharply more variety. During 1880–1930, more than 21,000 freestanding three-family homes were built in Boston, for instance. In 1940, Chicago had more than twice as many housing units in two-, three-, and four-family homes (382,028) as it had in single-family homes (164,920).15 Even affluent suburbs incorporated many housing types. Shaker Heights, a Cleveland suburb once synonymous with great wealth, reflects its 1920s origin in its current housing types: 56% of units are detached single-family homes, 20% are single-family attached houses or are found in two-unit structures (10.7%), three- or four-unit structures (2.3%), or five- to nine-unit structures (4.1%).16

Modern land-use regulations have ensured that areas developed after World War II have little diversity of housing stock. In San Jose, 53.4% of housing is single-family detached, and 10.9% is single-family attached; only 1.7% is two-family, and 10.3% is three- to nine-family. In Palo Alto, 62.9% is single-family, and just 1.7% is two-family. In Santa Clara County as a whole, 63.4% of housing units are single-family; in San Mateo County, 64.8%. San Jose and Palo Alto do have many buildings with 10 or more units (20.2% and 24.7%, respectively), far more than postwar suburbs such as Levittown, New York (94% single-family). But they have far less middle-density stock than prewar developments, such as Shaker Heights.17

The Case for the Missing Middle

Academic debates over housing policy often focus on narrow economic considerations and treat dwellings as interchangeable. But housing provides more than just shelter. Moreover, people’s housing tastes change throughout their lives. The existence of a housing ladder—made possible by having diverse types of housing—encourages upward mobility, too.

By buying a small multiunit building, entrepreneurial households can offset mortgage expenses by renting out additional units. And working-class owners with home-repair skills can augment rental income by renovating the buildings they own. Young families can buy a small condo and then save toward moving up the housing ladder to a single-family house or to a wealthier community, while serving as a replacement market of buyers for more expensive homes. Modern patterns of development, by contrast, offer unaffordable single-family homes as the alternative to renting an apartment indefinitely.

Missing-middle housing may also quicken Silicon Valley’s housing turnover. Realtor data confirm that expensive areas in California generally have very low turnover, partly because the property-tax cap imposed by Proposition 13 in 1978 discourages older homeowners who no longer need a multi-bedroom house from moving. Realtors who once “sold four or five homes a month now hope to sell one,”18 says Vince Rocha of the Santa Clara County Association of Realtors.

Older adults who are averse to moving into a new detached house may be willing to move to a smaller, less expensive unit with, say, a family living downstairs. For an elderly person, advantages of such an arrangement would include living in the same building (or in an accessory unit on the same lot) with neighbors who could help in an emergency—and who themselves might want help with babysitting. Smaller multifamily units, in other words, can be the wellsprings of community and companionship.

Strictly economic considerations should not be ignored, either. Middle-density housing often makes more economic sense than higher- and lower-density housing. As that long-ago company-town builder in Copake, New York, understood, putting more housing units on the same acreage reduces the cost of land per unit, while shared walls reduce heating and cooling costs.

Small multifamily housing is also much cheaper to build than high-rises. Small buildings can use inexpensive materials such as wood, while large towers—the other major housing type in Silicon Valley—require steel. This cost advantage has been made more attractive by sharp increases in construction costs; inflation-adjusted construction costs per housing unit in San Francisco have risen from $265,000 in 2000 to $420,000 today.19 Middle-density housing attracts more construction firms than do high-rises, too. “[I]t’s easier to attract more players because the risk is lower,”20says Peter Cohen of the San Francisco–based Council of Community Housing Organizations. Such competition may further reduce construction prices.

Finally, middle-density construction is prudential: as good investors know, a diverse portfolio is the best protection against market downturns. Cities that offer dense apartments as the only form of new housing put themselves at risk. San Jose may render itself vulnerable if public tastes shift away from high-rise apartment buildings, causing them to empty out or become derelict. Likewise, dense apartments may be put to unexpected uses that ultimately damage the community, such as pieds-à-terre purchased by wealthy absentee owners rather than members of the local workforce. High-density construction is often valuable, but cities that rely on it exclusively may be incurring unrecognized risks.

Some urbanists, recognizing that different housing types have different effects on communities, endorse small-scale multifamily housing. “Big, big, big is not necessarily good,” says Cohen. “Many people are simply more comfortable at lower- and mid-scale densities, from a four-story stick frame building in Pleasanton to an eight-story multifamily in western San Francisco.”21

The call for missing-middle housing extends beyond the Bay Area. In 2015, the mayor of Seattle convened a housing task force and charged it to find ways to build 30,000 new homes by 2025. The task force concluded that the city was “constrained by outdated policies and historical precedents,” such as single-family zoning of two-thirds of Seattle’s land. The committee proposed significant upzonings (permitting greater density) to allow new multifamily construction—including designating 6% of single-family areas for low-rise multifamily construction, as well as raising height limits in existing multifamily areas toward a 75-foot “sweet spot,” which would produce the lowest construction cost per unit.23

Siting the Missing Middle

In cities with large areas zoned single-family, planners and developers can face a challenge in siting missing-middle housing. Yet some sites seem especially well suited for it.

Commercial Corridors

Many neighborhood shopping streets have mostly low-rise structures used only for commerce. Slightly denser new construction could incorporate ground-floor retail and upper-floor residential uses, as is common in streetcar suburbs,24 where building owners often operate businesses and live upstairs. This approach aligns with San Jose’s goal of turning several commercial corridors, currently filled with large parking lots and car-oriented businesses such as fast food and gasoline, into pedestrian-friendly “urban villages.”25

Shopping Centers and Strip Malls

If zoning permitted residential construction in commercial areas, mixed-use housing might fit into the existing footprint, or it might simply replace buildings currently standing. In suburban sections of San Jose, such uses are already common. As bricks-and-mortar retail stores face a cloudy future, zoning commercial areas for other potential uses makes sense.

Parking Lots with Relaxed Parking Requirements

Open-air parking lots can lend themselves to intensive development of small, multifamily, owner-occupied buildings. Donald Shoup of UCLA notes that city zoning codes require businesses to devote large portions of their land to parking spaces, many of which are seldom used. In San Jose, according to Shoup,“[t]he area required for parking at a restaurant … is more than eight times larger than the dining area in the restaurant itself.”26

Office Parks

Campus-style office parks frequently contain underused open space that could be repurposed for housing. Critics of the idea worry that drawing people to live in such areas would boost automobile use because not all residents would also work at the office parks and those who didn’t would typically be far from public transit. Yet fears of increased congestion are likely overstated, as technology offers convenient new ways to get around. Office-park residents who commuted could, for instance, travel to transit and business hubs on private bus links modeled on ride-sharing services. “By ‘Uberizing’ existing private buses and shuttles—matching and dispatching varied trips through smartphones with the aid of trip-matching algorithms—[one] could stitch together transit threads into a cohesive network without compromising the direct, express-like connections passengers crave,”27 writes Alex Armlovich of the Manhattan Institute.

Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs)

An ADU is a smaller dwelling situated on the same grounds as (or attached to) a regular single-family house, such as an apartment built over a garage, a cottage built in a backyard, or a self-contained basement apartment. ADUs may be the most practical way to densify the single-family zones of Silicon Valley and other postwar suburbs. California state legislation encouraging ADUs took effect on January 1, 2018. It defines permitted ADUs, reduces parking requirements, and allows ADUs in single-family-zoned areas. The state Department of Housing provides a thorough list of the virtues of ADUs:

- ADUs are an affordable type of home to construct in California because they do not require paying for land, major new infrastructure, structured parking, or elevators.

- ADUs can provide a source of income for homeowners.

- ADUs are built with cost-effective wood frame construction, which is significantly less costly than homes in new multifamily infill buildings.

- ADUs allow extended families to be near one another while maintaining privacy.

- ADUs can provide as much living space as many newly built apartments and condominiums, and they’re suited well for couples, small families, friends, young people, and seniors.

- ADUs give homeowners the flexibility to share independent living areas with family members and others, allowing seniors to age in place as they require more care.28

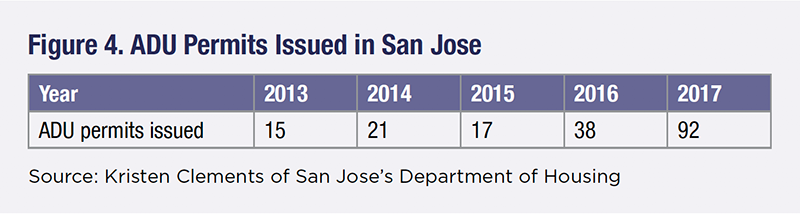

Further, ADUs may encourage housing turnover by allowing older homeowners to remain in their neighborhoods but to sell homes larger than they need, thus increasing the supply of housing and lowering prices. San Jose issued more ADU permits in 2017 than in the four prior years combined (Figure 4). Thanks to state laws encouraging ADUs, this growth is likely to continue.

Greenfields with Innovative Transit Links

Construction of housing on open, undeveloped “greenfield” land is discouraged in California, often out of concern that greenfield development will be car-oriented, space-wasting sprawl. In San Jose, an urban growth boundary places land in an “urban reserve” off limits to development. Environmental concerns have helped prevent the development of the city’s Coyote Valley, where a lapsed plan envisioned 25,000 new housing units.29

Yet greenfield development does not have to be suburban sprawl or dependent on private cars. New urban villages of two- to nine-unit buildings could be built near retail and office space if zoning permitted. Relaxed parking requirements could discourage car ownership while encouraging private transport operators to link residents to downtown areas and rail transit. On-demand transportation, which will likely soon include driverless cars parked at some distance from residential areas, can upend traditional suburban land use. New households may well be willing to compromise on “free parking”—the hidden costs of which are factored into housing and retail prices—in exchange for housing affordability.

Obstacles to Missing-Middle Development

Despite its virtues, missing-middle housing often faces opposition from neighborhood residents—“not in my back yard” protesters (NIMBYs)—and from city planners, though their motivations diverge. City planners often prefer even denser development, whereas NIMBYs prefer low-density development or, ideally, none at all.

Opposition from City Planners

City planners in California often “fiscalize” land use, designing housing regulations to maximize the city’s tax revenues and minimize spending on public services rather than accommodate market demand. And fiscal analyses typically find that residential development, except for the very densest, drains city finances.

A 2015 study commissioned by San Jose found that “residential uses require more in City services than they provide directly in City revenue.”30 The study notes that middle-density housing is not much better than single-family housing for city finances: “Low and medium density multifamily units create some efficiencies [compared with single-family houses] in terms of the lower amount of street pavement needed to serve higher density development, but also may create higher response requirements for police and fire services.”

This study led San Jose to conclude that it should encourage only new commercial or high-density residential development. (The study finds that developments ranging in density from 49 to 266 units per acre are profitable.) To reduce commuting, San Jose—which has fewer jobs than residents and largely serves as a bedroom community for Silicon Valley—has also encouraged job growth rather than residential growth.

Fiscalization of land use has made California city planners reluctant to allow residential development, especially if it replaces commercial property. In 2015, for example, one San Jose developer proposed building housing earmarked for teachers on an underutilized commercial site. The 12,000-square-foot site would have housed a hair salon and 14 housing units, but the city council voted 8–3 against rezoning the site for residential use. One member of the council justified her vote by pointing out that the conversion of 2,300 acres of commercial land to residential use over the previous 15 years had harmed the city’s tax revenue.31

However, the 2015 study merits some skepticism. First, it overstates the fiscal cost of children. Because of Proposition 13, state sources, not local property taxes, constitute the majority of California school funding, so school-aged children burden municipalities’ finances less than in other states. Second, the study misleadingly assumes that low- and middle-density households typically have three or more persons, effectively assuming that most such households have children. But the empirical evidence suggests otherwise. One analysis of a typical suburban housing market, for instance, found that 69% of households have no children.32

Third, the study ignores the vital distinction between the average fiscal impact of current developments and the marginal impact of an additional development. New infill development will probably generate more city revenue than the average existing development. For instance, Proposition 13 limits the tax assessments of existing homes but allows new homes to be assessed at market value, so new houses create more property-tax revenue than existing houses. Similarly, if residents of new developments are less likely to own cars than existing residents and do more of their shopping within walking distance of home, they will generate more revenue for the city through sales taxes. (The study identifies “retail leakage”—the roughly 30% of retail purchases that San Jose residents make in other cities—as a prime reason that housing burdens the city’s finances.)

Likewise, new developments will probably cost less in city services than the average current development. Schools in Silicon Valley are below capacity; one San Jose school district, motivated in part by declining enrollment, recently decided to close five of its 17 elementary schools.33 Thus, even if new development attracts families with children, few additional expenses will be required for school construction and maintenance. Similarly, redevelopment of existing developed land, unlike greenfield suburban development, requires no road or sewer extensions. A more thorough fiscal analysis would consider how the needs of new development differ from those of existing development. Such considerations would likely make middle-density development look far less costly, if not profitable.

Even if San Jose’s fiscal analysis were incontrovertible, fiscal considerations alone cannot determine land policy. The city’s fiscalization of land use has kept in place policies that ignore massive demand for new housing. These policies will inevitably make San Jose into a city of aged residents in detached houses and transient affluent young professionals in high-rise apartments, served by a working class forced into ever-lengthening commutes. Such a city is unlikely to remain healthy or viable for long.

NIMBY Opposition

New developments in Silicon Valley almost always encounter NIMBY opponents, who complain that more housing will congest traffic, make parking scarce, and ruin scenic views. Those familiar with the Silicon Valley housing market consider NIMBY opposition inevitable and have been at a loss to overcome it. Former San Jose mayor Chuck Reed states: “We’ve tried every kind of argument. I’ve argued that it’s wrong to deny others housing, that your kids won’t be able to live here, that without housing we can’t sustain the economy. They don’t care.”34 NIMBYs can be so adamant partly because strict zoning laws make current housing owners wealthier by restricting the supply of housing.35

Donald Shoup has suggested one way to reduce NIMBY opposition to a different goal: curbside parking meters. He proposes earmarking meter revenues for neighborhood improvements, such as “repairing sidewalks, planting street trees, and putting utility wires underground.”36 Shoup’s point is generalizable: neighborhood residents can be drawn away from NIMBYism if they see that new development brings concrete benefits. “If all parking revenue disappears into a city’s general fund,” Shoup writes, “business leaders and residents probably won’t campaign for meters.… Dedicating the revenue to paying for local public services can be the political software necessary.”37

Conclusion

Encouraging construction of new housing—especially housing that is affordable to middle-income families—can appear almost impossible, especially in high-income, high-demand areas with vociferous opponents of new development. In California, an overlay of state environmental regulations and tax laws makes residential development even harder.

The Golden State’s political class may finally be growing its will to fix the problem. A Democratic state senator representing San Francisco and San Mateo County sponsored legislation to require relaxed zoning near transit hubs. In May 2018, a less prescriptive bill—which allows municipalities to “upzone” with the aim of meeting 125% of local housing needs and which bars municipalities “from rejecting any residential project proposed on suitable land”—passed the state senate.38

Political support for accessory dwelling units appears to growing, too. One bill in the state senate requires jurisdictions to drop owner-occupancy requirements statewide, thus encouraging ADUs to be used as rental properties in otherwise single-family districts.39 In addition, Californians have begun to reflect on ways in which Proposition 13 inhibits housing sales and turnover, as owners avoid moving to maintain stable property tax bills.40

Powerful levers such as zoning are already controlled by municipalities. Municipalities decide whether to convert commercial zones to residential zones, whether to permit additional units within single-family zones, and whether to permit dense, new development on previously undeveloped sites. True, some developments will always be dogged by the threat of legal action. But modest densification, especially if it brings new neighborhood amenities, may well gain approval.

San Jose and other cities facing affordable-housing crises should consider the advantages of America’s pre–World War II development model, which did not view housing as one-size-fits-all. Greater supply and variety will make homes less costly and communities more diverse. These are benefits that surely make standing up to NIMBY opposition worthwhile.

Endnotes

- Author’s visit to Copake.

- Author’s conversation with Guardino.

- HSH.com, “The Salary You Must Earn to Buy a Home in the 50 Largest Metros,” May 22, 2018.

- Demographia.com, “13th Annual Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey,” Jan. 23, 2017.

- U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey (ACS), 2016 5-Year Estimates, “S2503, Financial Characteristics.”

- Ibid.

- Mary Schwartz and Ellen Wilson, “Who Can Afford to Live in a Home? A Look at Data from the 2006 American Community Survey,” U.S. Census Bureau, 2008.

- “S2503, Financial Characteristics.”

- William A. Fischel, Zoning Rules! The Economics of Land Use Regulation (Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, 2015), 24–25.

- The Economist, “Too Hot for Jobs: Why Silicon Valley’s Economy Isn’t Creating More Jobs,” May 19, 2012.

- Jennifer Wadsworth, “San Jose Mayor Sam Liccardo Unveils Ambitious Plan to Build 25,000 New Homes by 2022,” San Jose Inside, Oct. 3, 2017.

- ACS, “DP04: Selected Housing Characteristics,” 2016 5-Year Estimates.

- The source for this statistic computes the percentage to be 14%, though it (strangely) excludes permits with deed restrictions. When such permits are included for Santa Clara County—as the source does for other counties—the percentage is 16%. See Association of Bay Area Governments, “San Francisco Bay Area Progress in Meeting 2015–2023 Regional Housing Need Allocation,” April 2017.

- Issi Romem, “America’s New Metropolitan Landscape: Pockets of Dense Construction in a Dormant Suburban Interior,” BuildZoom.com, Feb. 1, 2018.

- U.S. Census Bureau, “1940 Census of Housing: Volume 2. General Characteristics.”

- “B25024, Units in Structure,” ACS, 2016 5-Year Estimates.

- Ibid.

- Author’s conversation with Vince Rocha. Rocha notes that higher prices and higher commissions help buffer agents from the effects of low turnover.

- Costs for a 100-unit affordable-housing building. See Carolina Reid and Hayley Raetz, “Perspectives: Practitioners Weigh in on Drivers of Rising Housing Construction Costs in San Francisco,” University of California at Berkeley, January 2018.

- Author’s conversation with Cohen.

- Ibid.

- City of Seattle, “Final Advisory Committee Recommendations to Mayor Edward B. Murray and the Seattle City Council,” July 13, 2015.

- Amanda Kolson Hurley, “Will U.S. Cities Design Their Way Out of the Affordable Housing Crisis?” Next City, Jan. 18, 2016.

- See, e.g., Sam Bass Warner, Jr., Streetcar Suburbs: The Process of Growth in Boston, 1870–1900, 2nd ed. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1978).

- City of San Jose, “Urban Village Plans Under Development.”

- Shoup advocates construction of “liner buildings” on street-adjacent edges of parking lots, to provide housing and to improve the streetscape. See Donald Shoup, The High Cost of Free Parking (Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2017), xxxiv.

- Alex Armlovich, “New York, Pave the Way for Uberized Bus Companies Like Chariot,” New York Daily News, May 3, 2017.

- California Department of Housing and Community Development, “Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs).”

- City of San Jose, “Coyote Valley Plan: A Vision for Sustainable Development,” April 2008.

- Doug Svensson, “Memo to John Lang,” City of San Jose, Apr. 10, 2015.

- KTVU.com, “City Leaders Reject South Bay Housing Proposal for Teachers,” Aug. 8, 2017.

- Haydar Kurban, Ryan M. Gallagher, and Joseph J. Persky, “Estimating Local Redistribution Through Property-Tax-Funded Public School Systems,” National Tax Journal 65, no. 3 (2012): 629–52.

- Sharon Noguchi, “In San Jose District, Identifying Schools to Close a Gut-Wrenching Prospect,” Mercury News, Dec. 26, 2017.

- Author’s conversation with Reed.

- Fischel, Zoning Rules!

- Shoup, The High Cost of Free Parking, xxviii.

- Ibid.

- Dennis Lynch, “Latest Bill to Boost Housing Statewide Takes a Step Forward,” TheRealDeal.com, May 31, 2018.

- Kol Peterson, “ADU Legislative Initiatives Abound,” AccessoryDwellings.org, May 2, 2018.

- See, e.g., Alan Greenblatt, “As Prop 13 Turns 40, Californians Rethink Its Future,” Governing, March 2018.

______________________

Howard Husock is Vice President for research and publications at the Manhattan Institute.

This piece originally appeared in Urban Policy 2018