An Ideological Screening Tool? DEI Statements Do Matter for Faculty Hiring, Evaluations

Introduction[1]

Diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) statements have become a popular additional criterion for academic hiring and promotion, with large numbers of universities or departments requesting or mandating their use for faculty hiring.[2] Yet little to no empirical research has assessed how university faculty actually evaluate these statements. As such, to date it has been unclear whether DEI statements (as styled by their proponents) operate as a supporting, additive component for faculty hiring or whether they are political litmus tests (as their critics argue) operating as a screening tool to reinforce ideological conformity, easily deployed to sift out academics holding dissenting views.

In this issue brief, data from seven survey experiments involving 4,953 tenured/tenure-track university faculty will be summarized. These studies stand as a robust, high-powered experimental assessment of how faculty evaluate DEI statements and what faculty think about them. These are the first experimental studies to investigate this topic. The results demonstrate that faculty exhibit a clear preference for DEI statements discussing race/ethnicity and gender and rate lower those that do not. Such outcomes suggest that DEI statements in this context are likely operating as an ideological screening device. The results from the present studies should prompt colleges and universities to reevaluate the purported goal, function, and use of DEI statements.

Background

The modern university’s increased focus on diversity has led to the use of DEI statements in the academy, most notably for faculty hiring and promotion. Styled as a way to “dismantle privilege” that perpetuates racial and ethnic disparities[3] or signal that a “department genuinely values equity, diversity, and inclusion,”[4] DEI statements are frequently marketed as a way for faculty applicants to be given credit for “invisible work” that previously would have been overlooked, ignored, or underappreciated.[5] In other words, they are purported to serve as an additive component in an application. Some proponents have also described DEI statements as a beneficial recruitment strategy for hiring faculty when affirmative action is prohibited.[67]

The University of California (UC) system has been a pioneer in the use and implementation of DEI statements for faculty hiring and promotion, and its leaders have been vocal in defense of the practice.[8] In 2015, system leaders decided that faculty achievement and efforts related to diversity should be recognized in academic personnel processes.[9] Many other institutions quickly followed suit, such that 22% of institutions surveyed in 2022 by the American Association of University Professors reported that DEI criteria were included in tenure standards, and an additional 39% had DEI criteria under consideration.[10]

Use and Application of DEI Statements

Despite the rising prevalence of DEI statements in academic hiring, some evidence suggests that universities do not always provide guidance on how to use DEI statements in hiring processes.[11] Additionally, it is generally ambiguous what types or combinations of diversity hiring committees are looking for: Do hiring committees desire broad and varied diversity actions and efforts from applicants or specific types of diversity actions and efforts? UC Berkeley, for example, articulates how the conceptualization of diversity can itself be quite diverse, stating that the institution “prize[s] diversity in all its forms” because “our excellence depends on diversity of thought and perspective.” This is then followed by a definition of diversity as:

The variety of personal experiences, values, perspectives, and worldviews that arise from differences of culture and circumstance. Such differences include race, ethnicity, gender, age, religion, language, abilities/disabilities, sexual orientation, gender identity, socioeconomic status, geographic region, perspective, and more.[12]

A definition such as this is fairly broad. But some claim that the range of acceptable forms of diversity in these contexts is typically limited, often to specific considerations or positions on race and gender[13] —if not in definition, then in practice. Furthermore, though many colleges and universities consider diversity to be a core value, DEI statements are almost exclusively required for faculty hiring, but not for staff or administrative hiring.[14] Such a dynamic raises questions about the purpose and intention of DEI statements.

DEI Statements as Screening Devices

Though DEI statements are often described as a supporting, additive component of faculty job applications,[15] and assurances are sometimes given that they are “not about penalizing faculty who do not promote [DEI],”[16] some hiring reports have indicated this is not always the case. Specifically, at some institutions, including UC Berkeley,[17,18] UC Santa Cruz,[19] and Cornell University,[20] public reports have detailed how DEI statements were intentionally used as a screening tool to reduce the number of applicants under consideration in a first round of review “based solely on contributions to diversity, equity and inclusion.”[21] Often this initial screening resulted in the mass elimination of hundreds of applicants.

Concerns About DEI Statements

Many have argued that the use of DEI statements is problematic.[22] Some have argued that DEI statements operate as a political litmus test[23] or that they threaten academic freedom.[24]

Critics also allege that DEI statements compel faculty to demonstrate allegiance to debatable political arguments about DEI. Legally, DEI mandates may “cast a pall of orthodoxy” over campuses[25] and could constitute compelled speech[26] and viewpoint discrimination.[27] Because of these or other concerns, 10 states (as of March 21, 2025; see Figure 1) have passed legislation to restrict the use of DEI statements for faculty hiring.[28] Additionally, some institutions, including the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), the University of Michigan, and the Harvard Faculty of Arts and Sciences, have walked back or prohibited their use.[29]

Yet it is unclear to what extent some of these institutions may have walked back DEI requirements. At the University of Michigan, for example, the DEI statement requirement was purportedly eliminated following the recommendation of a working group of faculty who concluded in part that, “as currently enacted, diversity statements have the potential to limit viewpoints and reduce diversity of thought among faculty members.”[30] But while the working group successfully advocated for the removal of standalone DEI statements, the group also recommended moving toward a model whereby faculty applicants are expected to incorporate DEI discussions within their teaching, research, and service statements instead. Thus, it is unclear whether the DEI statement requirement at the University of Michigan was truly eliminated or whether efforts are now being made to repackage and rebrand DEI statements. This recommendation mirrors that found in the 2024/25 Senate Search Guide at UC Berkeley, where search committees are encouraged to consider piloting the “integration of DEIB [diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging] into the expectations for the research statement, teaching statement, and a service statement, rather than as a standalone statement.”[31]

Critics of DEI statements have also raised concerns about using DEI statements as a screening tool that leads to a de-emphasis of other faculty capabilities. If researchers or teaching instructors are overlooked primarily due to a perceived deficiency in DEI credentials—overlooked without an evaluation of their teaching, research, or service records—some argue that this could produce downstream consequences for student learning, research activity, and publication quality.[32]

Faculty Opinions on DEI Statements

In two different large national surveys of U.S. university faculty, the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) found that faculty were split on whether colleges should require job applicants to submit a DEI statement as a prerequisite for being hired. In a 2022 survey, half of the faculty respondents said DEI statements are “a justifiable requirement for a job at a university,” while the other half said they are “an ideological litmus test that violates academic freedom.”[33] Similarly, in a 2024 survey, half of the faculty respondents indicated that DEI statement pledges in hiring are “never” or “rarely” justifiable.[34] At best, faculty opinions on DEI statements appear mixed.

Overview of Study

Given the mixed perspectives on DEI statements, as well as the nonexistence of any research on how faculty actually evaluate DEI statements, the present study sought to generate empirical data on the topic. The study sought to empirically test whether DEI statements (intentionally or not) are being used in the academy as a screening tool (or litmus test)[35] to reinforce ideological conformity and help sift out those holding dissenting views—or, conversely, if DEI statements are operating and being evaluated in an apolitical manner.

Study Design

Seven studies, identical in design, were conducted, using a total of 4,953 tenured/tenure-track university faculty,[36] recruited to evaluate the DEI statements of individuals who had ostensibly applied for a university faculty position. In each study, participants were randomly assigned to read and evaluate one of three DEI statements. The DEI statement that faculty participants read and evaluated was one of the following:

- An equalitarian DEI statement that discussed DEI actions and efforts related to race/ethnicity and gender (this was a statement shared online by UCLA as an exemplar[37]);

- An “alternate” DEI statement that discussed non-race/ethnicity or gender types of diversity; or

- A hybrid statement that combined elements from the equalitarian and “alternate” DEI statements.

In studies 1–4, the “alternate” form of diversity actions and efforts discussed was viewpoint diversity (see the exact text from an example in Figure 2). In study 5 the “alternate” was disability diversity, in study 6 rural diversity, and in study 7 socioeconomic diversity.

Faculty participants received no other information about the applicant other than what was in the DEI statement they read. The only factor that changed between each DEI statement read and evaluated by faculty (i.e., the experimental manipulation) was the DEI-related content each statement showcased (i.e., the DEI actions and efforts that the candidates discussed). Because all other information was held constant between experimental conditions, any differences in participants’ evaluations are attributable to the specific DEI content in each statement. A key comparison in each study was how faculty evaluated the DEI statement that did not mention race/ethnic or gender diversity actions and efforts (i.e., the “alternate” DEI statement) compared to the equalitarian and hybrid DEI statements.

There are a variety of reasons why the “alternate” forms of diversity actions and efforts were selected for study. First, viewpoint diversity was tested, as some researchers have argued that because ideological minorities are a notably underrepresented group in the academy,[38] a discussion of DEI efforts to help individuals in these groups would genuinely be relevant and on-topic for a DEI statement. Second, some have asserted that discussions of viewpoint diversity in a DEI statement would automatically result in lower evaluation scores,[39] making this an empirical question worth testing. I selected rural diversity for investigation because top U.S. universities (e.g., Yale, MIT, University of Southern California) have started to direct increased attention toward recruiting rural students,[40] given the low numbers of students from rural communities who enroll in college. I investigated socioeconomic diversity in part because of high participant endorsement (in studies 1–6) of this topic as a relevant topic to discuss in a DEI statement and because of increased awareness and focus on this as an important type of diversity.[41] Disability diversity was selected as a way to further probe the extent to which faculty may rate lower any DEI statement that does not discuss race or gender.

Faculty participants evaluated the DEI statement using five outcome variables. First, participants evaluated the DEI statement using preexisting DEI rubrics established for evaluating such statements. In studies 1, 2, and 4–7 this was UCLA’s DEI rubric;[42] in study 3 this was UC Berkeley’s DEI rubric.[43] Following that, faculty rated the applicant on other outcome variables including competence, hireability, likability, and whether or not they recommended advancing the applicant for further review (i.e., whether the applicant passed an initial screening). After evaluating the applicant, faculty answered questions on their opinions about DEI statements.

Additional information about the methods and materials, including the exact wording used in all of the DEI statements, can be found in the online academic preprint for these studies and in the online preregistration.[44]

A summary of the key results across the studies follows.

Results and Discussion

Differences in Evaluation—DEI Rubrics

Scores from the DEI rubrics are consequential because they are used for evaluating real job applicants at UCLA, UC Berkeley, and other institutions. Across all studies, statistically significant results emerged from these rubric scores. DEI rubric scores indicated that faculty evaluators perceived the “alternate” DEI statements to be weaker, less clear, and less effective statements on contributions to DEI compared to the hybrid and equalitarian (race/ethnicity and gender) statements (Figure 3). This was evident when the DEI statements were rated with both the UCLA DEI rubric (studies 1, 2, and 4–7) and the UC Berkeley DEI rubric (study 3). As such, given identical outcomes, both rubrics appear to function in a similar manner. Across the seven studies, faculty applied significant penalties to DEI statements that did not discuss race/ethnicity or gender (i.e., equalitarian) diversity actions and efforts, though the difference effects in study 5 for the disability diversity DEI statement were smaller and weaker compared to the other studies.

Differences in Evaluation—Competence

Faculty next evaluated the writer of the DEI statement they read on competence. Findings were similar to those for the DEI rubrics: for studies 1–4 and 6–7, statistically significant results emerged such that faculty evaluators perceived the “alternate” diversity statement writers to be less competent compared to the equalitarian and hybrid statement writers (Figure 4). But in study 5, faculty evaluators generally did not perceive the writer of the disability diversity statement to be less competent compared to the writer of the equalitarian DEI statement. As such, across six of the seven studies, faculty again applied significant penalties to DEI statements that did not discuss race/ethnicity or gender diversity actions and efforts.

Differences in Evaluation—Hireability

Third, faculty evaluators rated the DEI statement applicants for hireability. Across all seven studies, statistically significant results emerged such that faculty evaluators perceived the “alternate” DEI statement writer to have a decreased likelihood of hireability (Figure 5). That is, based only on the DEI statement they read, faculty perceived the “alternate” DEI statement applicants to be less hirable. Thus, again across the seven studies, faculty applied significant penalties to DEI statements that did not discuss race/ethnicity or gender diversity actions and efforts. But as with the prior outcome variables, the effect was smaller for study 5.

Differences in Evaluation—Likability

Next, faculty evaluators rated how much they liked the applicant whose DEI statement they read. For studies 1–4 and 6–7, statistically significant results emerged such that faculty evaluators liked the “alternate” diversity statement writers less compared to the equalitarian and hybrid statement writers (Figure 6). But in study 5, faculty evaluators generally did not perceive the writer of the disability diversity statement to be less likeable compared to the writer of the equalitarian DEI statement. As such, across six of the seven studies, faculty continued to apply significant penalties to DEI statements that did not discuss race/ethnicity or gender diversity actions and efforts.

Differences in Evaluation—Initial Screening

Finally, faculty indicated whether or not they recommended advancing the applicant for further review (i.e., whether the applicant passed an initial screening). This served as a blunt assessment for how a DEI statement may operate as a screening device. For studies 1–4 and 6–7, statistically significant results emerged such that faculty were less likely to recommend advancing the “alternate” DEI statement applicants for further review compared to the hybrid and equalitarian statement applicants (Figure 7).

For example, in study 3, the largest disparity emerged: Based solely on their reading of the DEI statement, less than half of faculty who evaluated the viewpoint diversity statement (45%) recommended advancing the applicant for further review, compared to 80% of faculty who evaluated the hybrid statement and 88% of faculty who evaluated the equalitarian statement. In study 5, no statistically significant differences emerged. Thus, across six of seven studies, faculty again applied a significant penalty to DEI statements that focused only on “alternate” actions and efforts. In the case of initial screening, this evaluative penalty would translate (in a practical sense) to a candidate being blocked from receiving a holistic evaluation (i.e., from having their teaching statement, research statement, letters of recommendation, and CV/résumé reviewed) simply because their DEI statement was deemed inadequate.

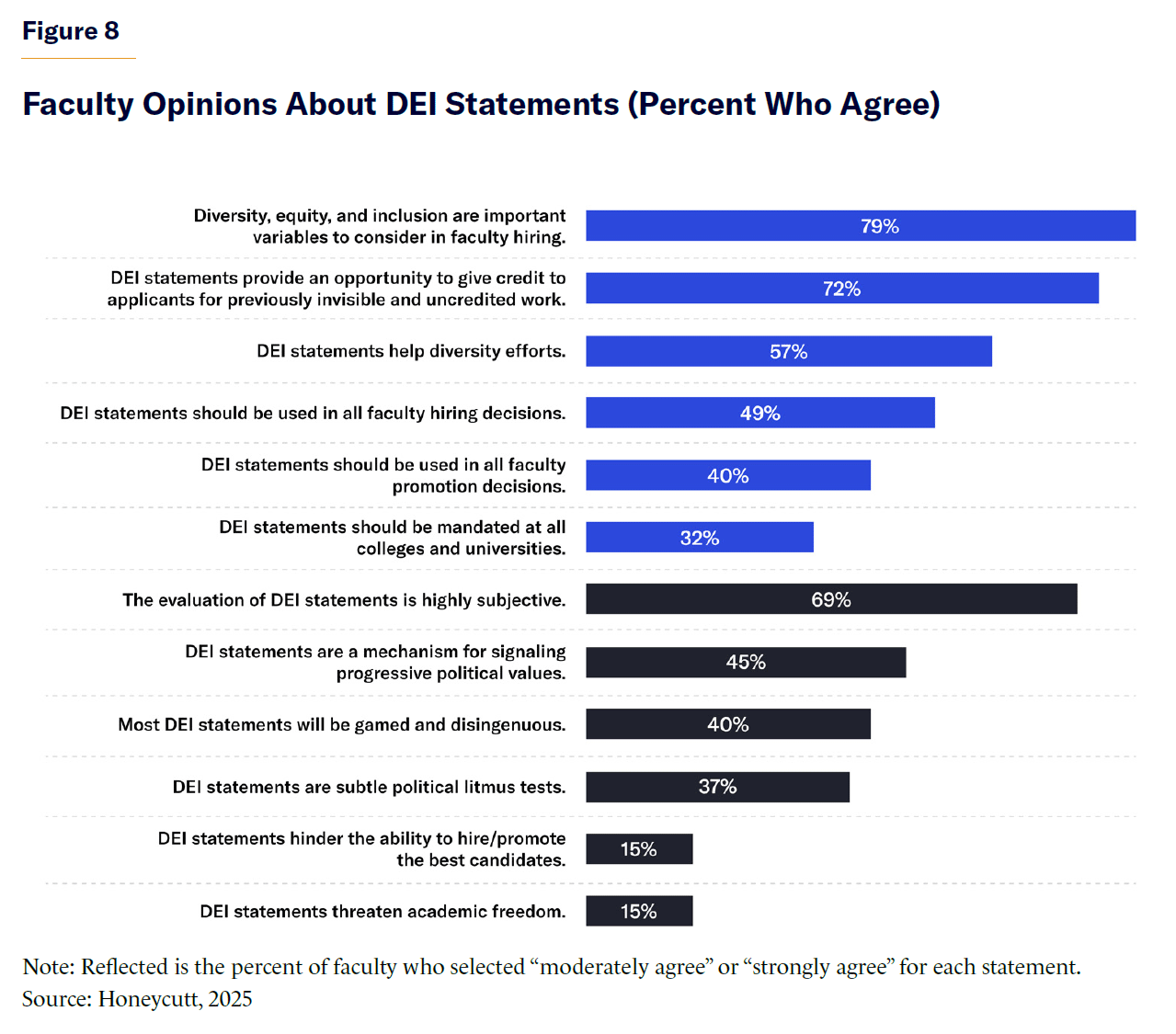

Faculty Opinions About DEI Statements

Across all seven studies, faculty were asked to give their opinions about various facets of DEI statements (Figure 8). Opinions were mixed. Notably, 79% of faculty participants agreed that “diversity, equity, and inclusion are important variables to consider in faculty hiring,” but 69% agreed that “the evaluation of DEI statements is highly subjective.” Furthermore, 57% agreed that “DEI statements help diversity efforts,” but 40% agreed that “most DEI statements will be gamed and disingenuous,” and 37% agreed that “DEI statements are subtle political litmus tests.”

Additionally, as shown in the original version of this report, nearly a quarter (23%) of faculty participants agreed both that “diversity, equity, and inclusion are important variables to consider in faculty hiring” and that “DEI statements are subtle political litmus tests.”

Faculty participants were also asked to indicate what topics they thought were relevant for applicants to discuss in their DEI statements. Large percentages indicated that race/ethnicity, gender, and socioeconomic diversity are relevant to discuss in DEI statements (Figure 9). However, given the broad and nonspecific nature of most DEI statement prompts, it is perhaps surprising that only four topics were considered relevant to discuss in DEI statements by a supermajority of faculty. This finding may go hand in hand with the experimental data in further suggesting that many faculty consider certain topics within or out of bounds for discussion in a DEI statement.

Additionally, given the high percentage of faculty endorsing socioeconomic diversity as a topic relevant to discuss, it is unclear why the socioeconomic diversity “alternate” DEI statement was rated lower than the hybrid and equalitarian DEI statements in study 7. If it was the case that faculty gave favorable evaluations to statements that discussed DEI actions and efforts that most faculty consider relevant, then the socioeconomic diversity DEI statement should have been rated higher, but this was not the case.

Analysis

These studies provide the first empirical data on how college/university faculty evaluate and perceive DEI statements in the context of faculty hiring. Across all evaluation outcome variables faculty applied an evaluation penalty, rating DEI statements that did not discuss race/ethnicity or gender lower. This evaluative penalty was most severe toward DEI statements that discussed only viewpoint diversity (studies 1–4) but was also of consequence for statements that focused only on rural diversity (study 6) or on socioeconomic diversity (study 7). The evaluative penalties reflected faculty perceptions that the “alternate” statements (compared to the hybrid and equalitarian statements) were weaker and that the applicants who submitted these statements were less competent, less hirable, and less likable. Furthermore, faculty were less likely to recommend—often by a large margin—that these “alternate” statements pass an initial screening. Findings related to disability diversity (study 5) were mixed.

Importantly, all DEI statements evaluated in these studies were on-topic, implicitly endorsed DEI, and focused on DEI actions and efforts, not personal beliefs or views on DEI. As such, it can be concluded that evaluative penalties in these studies stem from the applicants purportedly engaging in incorrect (or insufficient) DEI actions and efforts, not from holding incorrect views related to DEI. This distinction is important because some defenses of DEI statements argue that it would be acceptable to penalize candidates who refuse to discuss DEI efforts or actions or whose discussions are not on-topic.[45] But that was not the case here, as each of the DEI statements evaluated included an earnest and forthright discussion of DEI actions and efforts.

Additionally, it is noteworthy that across all studies, the hybrid statement was consistently evaluated similar to the equalitarian DEI statement. Thus, in principle, faculty were not unilaterally opposed to “alternate” DEI actions and efforts; contrary to expectations, these statements were not tainted by the different DEI actions and efforts discussed. Such findings suggest that faculty do not necessarily outright reject the validity of “alternate” types of DEI actions and efforts; they just might pale in importance to others such as race or gender. As such, the evaluative penalties may have more to do with a failure to discuss race/ethnicity and gender DEI actions and efforts than with having discussed “alternate” diversity actions and efforts.

In other words, the problem appears to lie in what was not discussed in these DEI statements rather than in what was discussed. Looking at it another way, two DEI statement conditions were missing something: The equalitarian DEI statement did not discuss “alternate” forms of diversity, and the “alternate” diversity statements did not discuss race/ethnicity or gender. But across these studies, only the “alternate” diversity statements were penalized.

In general, faculty evaluators appeared to be looking for specific answers when evaluating the DEI statements. Data from these seven studies suggest that a candidate submitting a DEI statement that does not discuss equalitarian forms of diversity actions and efforts—especially if the statement focuses solely on viewpoint diversity—would be rated poorly.

The results indicate that in this sample (and perhaps in much of higher education), many faculty consider race/ethnicity and gender essential for applicants to discuss in their DEI statements—so essential, in fact, that an applicant who does not mention them would generally be rated as having a poorer-quality DEI statement. Though high percentages of faculty in these samples reported supporting the use of DEI statements and agreeing with common claims about the benefits of using them, noteworthy percentages also agreed with some of the concerns that critics have raised.

Implications

DEI statements are often defended under the premise that they create an opportunity for applicants to receive credit or “due recognition” for important actions and efforts that otherwise would be overlooked.[46] While this may be true in theory, results from the present studies raise the question of whether the purported goal and desired function of DEI statements match how they are treated and evaluated by faculty in practice. Put differently, if DEI statements discussing racial/ethnic and gender diversity are rated higher than those that do not, does this mean that these are the primary types of diversity desired in the academy?

The evaluative outcomes across these studies also raise the question of whether DEI statements operate as a gatekeeping tool. Consider, for example, faculty ratings on the screening questions. Substantial percentages of faculty evaluators recommended (based solely on the DEI statement they read) that the writers of the “alternate” DEI statements (except for disability diversity) should not be advanced for further review. Practically, this indicates that such candidates would not be holistically evaluated, regardless of their strengths, proficiencies, or laudable accomplishments in teaching or research. This dynamic would effectively prevent such candidates from being hired and is inconsistent with assurances that these statements “are not about penalizing faculty who do not promote [DEI].”[47]

Results from these seven studies, given the obtained effect sizes (r-range across all studies: 0.07 to 0.42; median r=0.28), suggest that the differences in evaluation are nontrivial and meaningful. Specifically, the magnitude and consistency of obtained effect sizes suggest that how DEI statements are evaluated could translate into large real-world disadvantages for applicants to faculty jobs who fail to discuss race/ethnicity or gender DEI actions and efforts.

Although DEI statements are still a relatively recent development and trend at the faculty hiring level, they are starting to be proliferated and incorporated in other areas of the academy, such as graduate student admissions[48] and academic conference submissions.[49] Given the 2023 Supreme Court ruling impacting affirmative action in college admissions in the U.S.,[50] more institutions may turn to DEI statements as an alternate recruitment strategy.[51]

Finally, across all seven studies, the careful selection of participants,[52] the large samples of tenured/ tenure-track faculty that participated in the studies, and the use of a randomized controlled design with basic established audit study methodologies support a high degree of validity for the findings for the broader academy. The methods employed allow for at least a moderate amount of generalizability relative to an approach using a smaller and/or less geographically diverse sample or a sample of non-expert participants.

Conclusion

The present studies provide the first empirical evidence bearing on how faculty evaluate DEI statements for academic hiring. The results demonstrate that faculty appear to prefer DEI statements that discuss specific types of DEI actions and efforts. Specifically, across these studies, faculty expressed a preference for DEI statements that included a discussion of race/ethnicity and gender DEI actions and efforts and rated lower those statements that neglected to include such content.

The results from the present studies could have academic-freedom implications and are pertinent for hiring committees, departments, and colleges or universities that may be using DEI statements for any evaluative purpose, or for those that may be considering their adoption.

Endnotes

Photo: skynesher / E+ via Getty Images

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).