Observers of America’s suicide crisis have noticed something peculiar in the past year. Rates of depression and suicidality have surged, likely spurred by the COVID-19 crisis and ensuing lockdowns and economic turmoil. But suicide rates are flat or down across countries, including in the United States, where suicide rates may have actually fallen for the first time in decades.

This outcome was what the data augured as far back as January, as I previously wrote for IFS. The case has only gotten stronger since then: In a review of the evidence, psychiatrist and blogger Scott Alexander notes that suicidal ideation doubled in spring 2020 compared to spring 2018, while rates of depression tripled in late March and early April of 2020. Yet the best data from the CDC suggest that

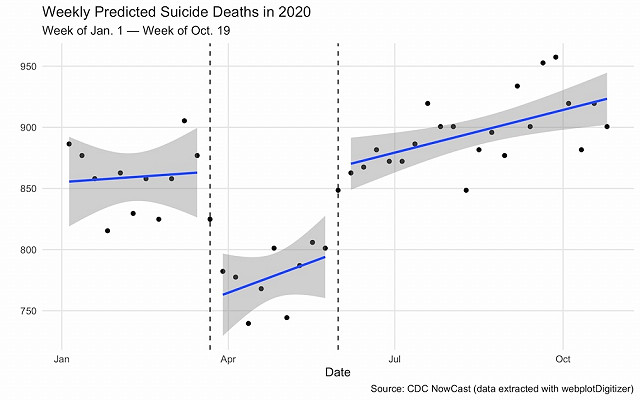

Predicted weekly numbers of suicide deaths were similar to historic levels in early 2020, then declined from March through June, and remain slightly lower than historic levels in more recent months.

Theories about what’s going on, Alexander notes, have tended to explain the disjuncture in terms of the pandemic—the crisis brought people together, reducing suicide even as it drove up suicidality. But that theory is not only not well-supported by the evidence; it’s also missing a key part of the story.

The divergence of suicide and suicidality is not new, but a consistent feature of the decades-long suicide crisis—a longstanding but underdiscussed mystery. The unexpected suicide drop during COVID may tell us something about that divergence, and about the suicide crisis more generally, suggesting that proximity to others is at least as important in preventing suicide as state of mind.

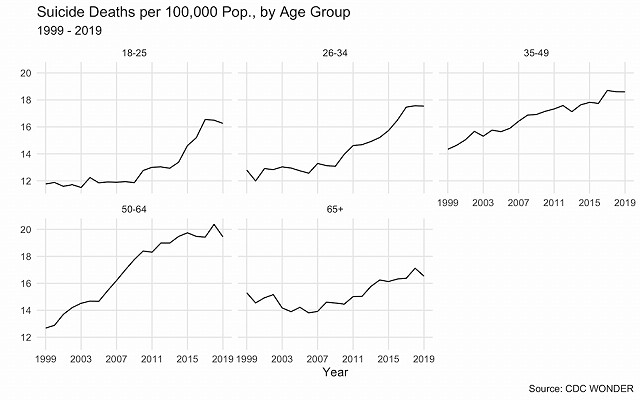

After over a decade of decline, in 1999, the American suicide rate began rising relentlessly, a trend which likely did not abate until last year. Suicides have risen across age groups, with large increases particularly among middle-aged white people, but also even among teenagers.

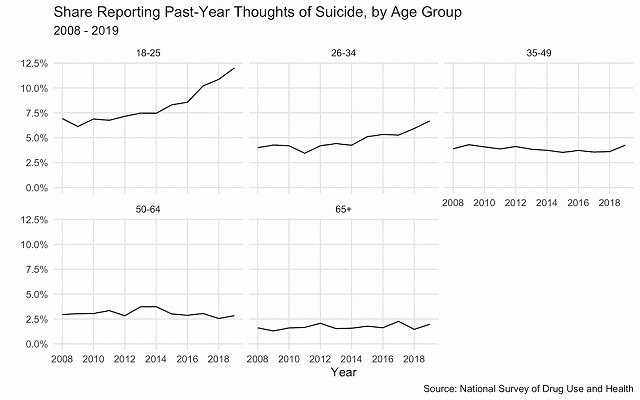

One of the many paradoxes of this increase, however, is that an increase in rates of suicide has not gone hand-in-hand with an increase in the rates of suicidality, as measured by self-reported cases of thinking about, planning, or attempting suicide. Suicidality has increased markedly among younger Americans, especially teenagers and those under 30, prompting concerns about a youth mental health crisis. But while older Americans have also seen large increases in suicide rates, their reported rates of suicidal ideation have been flat in at least the past decade.

The COVID-19 crisis appears to have preserved this disconnect, albeit in the opposite direction: suicidality rose, while suicide fell.

Although subject to the limits of modeled results, the CDC’s estimates of weekly suicides over 2020 paint a surprising picture. For the first several months of 2020, there were about 860 suicides per week in the United States. Then, in mid-March, as nationwide stay-at-home orders took effect, suicides dropped to an average of 780 per week. Starting in June, however, as lockdowns lifted, the suicide rate returned to prior levels.

In other words, being under lockdowns—arguably one of the most stressful events in modern American history—was associated with a significant reduction in suicides, even as it is linked to a large increase in stress.

Last year thus adds further evidence that the determinant of increases in suicide is not exclusively, or even primarily, increases in the level of suicidality in the population. That implies some other factor implicated in the suicide “process” but unrelated to emotional state is at play. Increasing firearms possession, for example, is often cited as a cause (although about two-thirds of the suicides “added” since 1999 are attributable to a cause other than gun deaths, making this an unsatisfying theory).

The COVID divergence actually suggests a different explanation: forcing people to stay at home, often with other family members or roomates or live-in romantic partners, reduced their opportunity for suicide, even as it potentially increased their motive for it.

Although lockdowns reduced our day-to-day interaction with others (leading, e.g., to spikes in loneliness), it put many people in closer quarters with a more restricted set of peers. Most Americans, particularly those under 75, do not live alone. And if anything, COVID lockdowns induced an increase in the number of Americans living with others, as it sent numerous young adults home to live with their parents.

Such social proximity may affect suicide through multiple causal pathways. One is that proximity to family may make us happier and less lonely. But even if it doesn’t do that—or even if it does not do so enough to offset the stress of a global pandemic, as was apparently true in 2020—it also facilitates what we might call “social surveillance,” making it harder to commit suicide for the simple reason that there are fewer opportunities to do so.

This mechanical explanation tells us something about suicide rates in the world before and after lockdowns: personal isolation, and particularly a lack of family formation, are likely contributing to rising suicide rates.

As I showed in a prior analysis for IFS, being married is highly protective against suicide, while being divorced is a major risk factor, such that divorced Americans were something like four times more likely to commit suicide than married Americans as of 2017. Some of this effect is driven by marriage’s effects on well-being (and some of it by selection), but it is likely that having a spouse also reduces your opportunity for suicide.

Yet as we know, rates of marriages have been in decline, as first marriage ages creep later and later; and while divorce rates are down (as a byproduct of declining marriage), “gray divorce” has risen. As of 2019, Census Bureau data show, 32.5% of the over-25 population were both unmarried and had no children at home, compared to 25.8% at the turn of the millennium.

This slow breakdown of the household has been happening longer than the suicide spike, but it likely still plays a role in worsening it. What the COVID suicide/suicidality suggests is a powerful role for such connections in preventing suicide—not necessarily by preventing suicidal thought, but by preventing the conversion of that thought into action.

______________________

Charles Fain Lehman is a fellow at the Manhattan Institute and a contributing editor of City Journal.

This piece originally appeared in Institute for Family Studies