The Right Price for Curb Parking

Editor's note: The following is the second chapter of Retooling Metropolis (2016) published by the Manhattan Institute.

Introduction

Everybody wants to park free, including me, but the only thing worse than paying for parking is having no parking at all. If curb parking is free, it is often crowded, and new arrivals have no place to park. Cities can install parking meters to avoid overcrowding, but what is the right price to charge? I will argue that the right price for curb parking is the lowest price that can produce one or two vacant parking spaces on each block. If many spaces are vacant, the price is too high. If no spaces are vacant, the price is too low. But if one or two spaces are vacant, the price is just right, and everybody will have great parking karma. Call it the Goldilocks principle.

Prices that produce one or two open curb spaces on every block will improve the city in three ways. First, and most obviously, curb parking will improve because the spaces will be well used yet readily available. Second, drivers won’t have to cruise to find an open space, which means less congestion, wasted fuel, and air pollution. Third, the economy will improve because customers will park, buy something, and leave promptly—freeing up spaces for other customers.

Cruising is an especially big problem. In 2006, researchers who interviewed drivers stopped at traffic lights on Prince Street in Manhattan found that 28% were hunting for curb parking.[1] In a study in 2007, researchers found that cruising for underpriced parking on 15 blocks on the Upper West Side of Manhattan created about 366,000 excess vehicle miles traveled per year.[2]

Although the demand for curb parking can vary throughout the day, parking meters in most cities charge the same price all day. Primitive technology once made it difficult to charge prices that vary throughout the day in response to changes in demand. Parking was, for decades, the most stagnant industry outside North Korea, but it is now taking advantage of everything that Silicon Valley has to offer. The new parking technology makes better parking policies possible, and the new parking policies increase the demand for the new technology.

The real barrier to implementing the Goldilocks principle for parking is not technoogy but politics. I will explain how cities have all the technology necessary to charge market prices for curb parking, using San Francisco as an example. Then I will explore how cities can make market prices for curb parking politically popular.

I. The Right Prices for Curb Parking in San Francisco

In 2011, San Francisco adopted the biggest price reform for onstreet parking since the invention of the parking meter in 1935: it varied the price of curb parking by both location and time of day. SFpark aims to solve the problems created by charging too much or too little. If the price is too high and many curb spaces remain vacant, nearby stores lose customers, employees lose jobs, and governments lose tax revenue. If the price is too low and no spaces are vacant, drivers who cruise to find an open space waste time and fuel, congest traffic, and pollute the air.

In seven pilot zones across the city—with a total of 7,000 curb parking spaces—San Francisco installed sensors that report the occupancy of each curb space on every block and parking meters that charge variable prices according to location and time of day. The city adjusts prices every two months or so in response to occupancy rates, increasing prices if occupancy is too high and reducing prices if occupancy is too low.

Consider the resulting prices of curb parking on a weekday at Fisherman’s Wharf, a popular tourist and retail destination (Figure 1):

Before SFpark began in August 2011, the price for a space was $3 an hour at all times. Now each block has different prices during three periods of the day—before noon, from noon to 3 p.m., and after 3 p.m. By May 2012, most prices had decreased in the morning hours. While some prices increased between noon and 3 p.m.—the busiest time of the day—most prices after 3 p.m. were lower than in midday though higher than in the morning. Prices changed every six weeks, never by more than 25 cents per hour. SFpark based these price adjustments purely on observed occupancy. City planners cannot reliably predict the right price for parking on every block at every time of day, but they can use a simple trial-and-error process to adjust prices in response to past occupancy rates. San Francisco charges the lowest prices possible without creating a parking shortage. This process of adjusting prices based on occupancy is sometimes called “performance pricing.” Figure 2 illustrates how nudging prices up on Block A, a crowded block, and down on under-occupied Block B can shift a single car to improve the performance of both blocks.

Beyond managing the on-street supply, SFpark helps to depoliticize parking. Transparent, data-based pricing rules can bypass the usual politics of parking. Because demand dictates the prices, politicians cannot simply raise them to gain more revenue.

While it is clear that demand-based parking prices are efficient, are they fair? In San Francisco, 30% of households do not own a car, so they don’t pay anything for curb parking. San Francisco uses all its parking-meter revenue to subsidize public transit, so automobile owners subsidize transit riders. SFpark furthers aids bus riders, cyclists, and pedestrians by reducing the traffic caused by cruising for underpriced and overcrowded curb parking.

SFpark’s goal is to optimize occupancy, not to maximize revenue, and prices go down as well as up. Because the prices at most meters had been too high in the mornings, the average price of curb parking fell by 4% during SFpark’s first two years. Varying the prices for curb parking by location and time of day aroused almost no political opposition, especially because the prices changed slowly and more prices went down than up. Most drivers didn’t even seem to notice that prices were changing. Opposition did erupt, however, whenever the city proposed new parking meters on blocks that had previously been free. So I will turn next to policies that cities can adopt to make parking meters politically popular.

II. Parking Benefit Districts

If all the parking-meter revenue disappears into a city’s general fund— as it now does in most cities—few businesses or residents will want to support charging for on-street parking. But if meter revenue is dedicated to specific, additional public services in the metered neighborhood, residents will be much more inclined to support performance pricing.

As a way to appeal to local stakeholders, some cities have created Parking Benefit Districts that spend the meter revenue only in the metered areas. Everyone who lives, works, visits, or owns property in the district can readily see the benefits paid for by the parking meters.

Old Pasadena, a historic business district in Pasadena, California, illustrates the potential of Parking Benefit Districts. Old Pasadena began to improve dramatically when the city installed parking meters in 1992 and began spending revenue of more than $1 million a year to rebuild the sidewalks, plant street trees, add historic street furniture, and increase police patrols. Parking revenue helped to convert what had been a commercial skid row into a popular destination.[3] Following the example of Pasadena, several other cities, including Austin, Houston, Mexico City, San Diego, and Washington, D.C., have committed parking revenue to finance public services on the metered streets.[4] Thus far, Parking Benefit Districts have been adopted almost entirely in commercial areas. A key question is whether they can also work in residential neighborhoods where everyone is accustomed to free parking on the street.

Currently, most cities issue residential parking permits either free (as in Boston) or at a low price (such as $34 a year in Los Angeles) for all the cars registered at each address. Although cities create permit districts only in neighborhoods where parking is scarce, they can be freewheeling about the number of permits they issue. For example, a political storm erupted in San Francisco in 2002 when journalists discovered that romance novelist Danielle Steel had 26 residential parking permits for her house in Pacific Heights.

What would it look like to institute a Parking Benefit District in a residential zone? First, drivers pay market prices for the permits. Second, the number of permits is limited to the number of curb spaces. Third, the permit revenue pays for neighborhood public services on the permit blocks.

Conventional residential permits are usually priced far below the market price because car owners resist paying to park in front of their own homes. The political incentives change drastically, however, when the majority of residents park off-street or don’t own a car and the parking revenue pays for neighborhood public services. The residents’ desire for public services can outweigh the motorists’ desire to park free on the streets.

Can charging market prices for on-street parking permits produce enough revenue to pay for public services in residential neighborhoods? I believe that they can. In the next section, I will outline the best way to price parking permits.

Uniform-price auctions

If a residential neighborhood wants to implement a Parking Benefit District, the simplest way to discover the market price is through a uniform-price auction. Here is an example of how it would work: each resident on a block with 20 parking spaces is allowed to submit a bid for one permit. The bids are ranked in descending order, and the highest 20 bidders receive permits. All the winning bidders then pay the same price: the lowest accepted bid. All but the lowest winning bidder thus pay less than what they actually bid. (Some universities use uniform-price auctions to sell campus parking permits.)

The auction price for street parking is the lowest price that will not create a shortage of parking and the price that will presumably compete with the market price of nearby off-street parking. For example, if residents can rent parking in a nearby garage, that price should put a ceiling on what residents are willing to bid for a permit to park on the street. If the monthly rent in the nearest garage is $100 a month, for example, this seems a reasonable estimate for the auction value of a permitted parking space on the street.

Although $100 a month ($3.30 a day) may seem a lot to pay for a permit to park on the street, drivers receive guaranteed parking spaces—a valuable asset in a neighborhood where street parking had previously been a gamble. Furthermore, because the revenue from parking permits pays for public services, the combination of guaranteed parking and the new public services may persuade even car owners to support a Parking Benefit District. A few spaces on each block could have conventional parking meters to accommodate visitors.

If the auction price is $100 a month, 20 permits will yield total annual revenue of about $24,000 to pay for public services on the block. Each block will require a separate auction because the demand for and supply of on-street parking varies by location. The auctions can be repeated every year, and the permits can be transferrable. Cities that are not equipped to manage the permit auctions can contract with e-commerce companies such as eBay that specialize in online auctions.

An alternative to alternate-side-of-the-street parking regulations

In addition to providing guaranteed curb spaces, a Parking Benefit District can eliminate the frustrating requirement that residents move their cars from one side of the street to the other on street-cleaning days. As Calvin Trillin showed in his brilliant novel Tepper Isn’t Going Out, alternate-side parking creates a nightmare for residents who park on the street. If cities use parking revenue to pay for vacuum equipment to clean around and under parked cars, streets can be swept without requiring drivers to move their cars.

To be sure, vacuum cleaning will require hiring more personnel and replacing conventional street-sweeping vehicles with new equipment. But ending the requirement to move cars back and forth may increase the auction value of parking permits by more than the cost of the vacuuming. If so, there will be revenue to pay for additional public services.

Discounts for shorter and cleaner cars

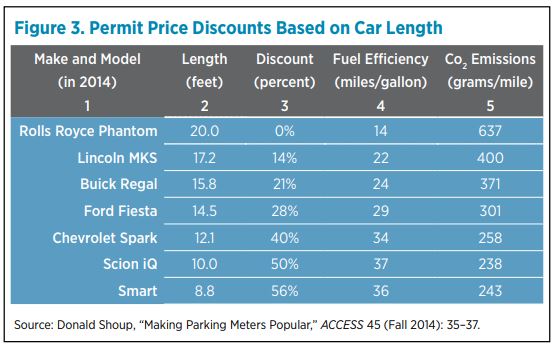

How many cars can park on a block in a Parking Benefit District? That depends on the length of the block and the size of the cars. To encourage drivers to economize on curb space, the city can give discounts on the permit prices for smaller cars. In addition to taking up less space, smaller cars tend to be more fuel-efficient, so discounts for smaller cars will reduce fuel consumption and CO2 emissions.

Figure 3 illustrates parking discounts based on car lengths. Column 1 shows a selection of cars, and Column 2 shows their lengths, ranging from 20 feet for a Rolls Royce down to 8.8 feet for a Smart car. Column 3 illustrates the discount for each car based on its length. Because the Rolls Royce is 20 feet long, it pays the full price, while the 10-foot Scion receives a 50% discount. Two Scions pay the same as one Rolls Royce, so the payment per foot of curb space is the same for both cars.

Column 4 shows each car’s fuel efficiency, ranging from 14 miles per gallon for the Rolls Royce up to 37 miles per gallon for the Scion. Finally, Column 5 shows each car’s CO2 emissions. For example, the Ford emits less than half as much CO2 as the Rolls Royce.

Cities with serious air pollution can also consider giving parking discounts for cars with low hydrocarbon or nitrogen oxide emissions. Parking meters in Madrid, Spain, for example, charge 20% less for clean cars and 20% more for dirty cars. Prices are the most reliable way for cities to send signals about the behavior that they want to encourage. If cities give discounts on permit prices for smaller and cleaner cars, more people will drive them.

Political prospects of Parking Benefit Districts

To examine the political prospects of charging for street parking to finance public services, we need to look at the demographics in a city that would benefit from this policy. Consider Manhattan, where 78% of households do not own a car (Figure 4). The carless majority will receive better public services without paying anything, and they outnumber car owners by more than three to one. In some especially dense neighborhoods, such as Chinatown, carless residents outnumber car owners by more than 10 to one. And even among car owners, many park in expensive lots and garages rather than on the street. Where a large majority prefers better public services to free curb parking, a Parking Benefit District may be politically feasible.

The motoring minority are also wealthier than the carless majority (Figure 5). Because car-owning households have much higher incomes than carless households, charging for parking to pay for public services seems fair.

Charging fair market prices for on-street parking can raise money to repair broken sidewalks, plant street trees, install security cameras, or remove the grime from subway stations. In dense neighborhoods, few will pay for on-street parking, but everyone will benefit from the public services.

Most existing parking-meter revenue has already been spoken for, often in complex ways. Because most cities now receive no revenue from on-street parking in residential neighborhoods, Parking Benefit Districts have the advantage of providing an entirely new source of public revenue.

Power equalization

Parking Benefit Districts allow each neighborhood to decide whether to charge for curb parking and how to spend the resulting revenue. Such a pointillist style of public finance can lead to more rational decisions about parking policies as well as public services.

Still, if more affluent neighborhoods have a higher demand for curb parking, they will earn more revenue than poorer neighborhoods, which seems unfair. Suppose, for example, rich neighborhoods earn an average revenue per curb space of $5,000 a year ($14 a day) while poor neighborhoods earn only $500 a year ($1.40 a day). In this case, rich neighborhoods would receive 10 times more than poor neighborhoods. How can a city avoid this inequality and still provide local incentives to charge for curb parking?

One option is to employ what in public finance is called “power equalization.” Suppose the average revenue per curb space is $2,000 a year. In this case, the city can spend $1,000 a year per space for added public services in each Parking Benefit District and spend the other $1,000 for citywide public services. All neighborhoods that charge market prices for their curb parking thus receive the same revenue per space; equal effort will produce equal results everywhere. Even neighborhoods that do not charge for curb parking can benefit from the citywide public expenditures.

Power equalization can transfer money from more affluent to less affluent neighborhoods and yet maintain the incentive for every neighborhood to charge for curb parking. To further increase the political appeal of the policy, the city can dedicate the citywide share of parking revenue to pay for highly visible public services, such as cleaning subway stations or installing bus shelters.

Giving money to Parking Benefit Districts according to the number of parking spaces might lead residents to oppose using the curb lanes for anything except parking, such as to make room for a bus lane or bike lane. To avoid this problem: where the city prohibits curb parking, it can give the districts an equivalent amount of money per foot of curb space.

Conclusion: Turning Problems into Opportunities

Decisions about parking are political, and the prospects for parking reform depend on what the political context allows. Parking Benefit Districts can appeal to people across the political spectrum. Liberals will see that a Parking Benefit District increases public spending. Conservatives will see that it relies on markets to allocate scarce land. Libertarians will see that it relies on individual choices rather than regulations. Drivers of all political stripes will see that it ensures guaranteed curb parking and removes the requirement to move their cars for street cleaning. Residents will see that it pays for public services. Environmentalists will appreciate that it reduces energy consumption, air pollution, and carbon emissions. Neighborhood activists will celebrate the fact that it allows key public decisions to be made at the local level. Local elected officials will see that it depoliticizes parking, reduces traffic congestion, and pays for public services without raising taxes.

Yet people also want to park free. They may not have an ideological or a professional interest in free parking, but they do have a personal interest in it. Nevertheless, strategic use of the parking revenue can create a countervailing personal interest in charging for curb parking. Cities can create the necessary political support for priced parking by dedicating the resulting revenue to pay for public services on the metered streets.

Any city can offer a pilot program to charge for on-street parking and use the revenue to finance public services. If residents don’t like the results, the city can cancel the program and little will be lost. If residents do like the results, however, the city can offer this self-financing program in other neighborhoods. Because neighborhoods will have money to spend and decisions to make, residents will gain a new voice in governing their communities.

This simple parking reform may be the cheapest, fastest, and simplest way to improve cities and create a more just society, one parking space at a time.

References and Additional Reading

Martin, Elliot, and Susan Shaheen. 2011. “The Impact of Carsharing on Household Vehicle Ownership.” ACCESS 38: 22–27.

Orlove, Raphael. 2014. “Hell Is Street-Parking Two Broken Cars in Manhattan.” Kinja, Sept. 25.

Pierce, Gregory, and Donald Shoup. 2013. “SFpark: Pricing Parking by Demand,” ACCESS 43: 20–28.

Schaller, Bruce. 2006. “Curbing Cars: Shopping, Parking and Pedestrian Space in SoHo.” New York: Transportation Alternatives.

Shoup, Donald. 2007a. “Gone Parkin’.” New York Times, Mar. 29.

———. 2007b. “Cruising for Parking.” ACCESS 30: 16–22.

———. 2011. The High Cost of Free Parking. Chicago: Planners Press.

———. 2014. “Making Parking Meters Popular.” ACCESS 45: 35–37.

———. 2015. “Informal Parking: Turning Problems into Solutions.” ACCESS 46: 14–19.

———, Quan Yuan, and Xin Jiang. Forthcoming. “Charging for Parking to Finance Public Services.” Journal of Planning Education and Research.

Transportation Alternatives. 2007. “‘No Vacancy’: Park Slope’s Parking Problem and How to Fix It.”

———. 2008. “Driven to Excess: What Underpriced Curbside Parking Costs the Upper West Side.”

Trillin, Calvin. 2001. Tepper Isn’t Going Out. New York: Random House.

Endnotes

- Bruce Schaller, “Curbing Cars: Shopping, Parking and Pedestrian Space in SoHo,” Transportation Alternatives, Dec. 14, 2006.

- Transportation Alternatives, “Driven to Excess: What Under-Priced Curbside Parking Costs the Upper West Side,” June 2008.

- Douglas Kolozsvari and Donald Shoup, “Turning Small Change Into Big Changes,” ACCESS 43 (Fall 2003): 27.

- See austintexas.gov; houstontx.gov; Andrés Sañudo et al., “Impacts of the ecoParq Program on Polanco: Preliminary Overview of the Parking Meter System After One Year Running,” Institute for Transportation and Development Policy Mexico, 2013.