Reimagining Rikers Island: A Better Alternative to NYC’s Four-Borough Jail Plan

Six months before the Covid-19 epidemic spread across New York City in early March, Mayor Bill de Blasio and the city council approved a plan to spend nearly $9 billion over the next half-decade to build four jails, one each in the Bronx, Brooklyn, Manhattan, and Queens. The completion of the new jails, in turn, would allow the city to close Rikers Island, home to most existing jail facilities.

The mayor and the council are right in one respect: the jail facilities on Rikers are deficient. One way or another, New York must invest billions to make good on its promise to treat detainees—most of whom have not yet been convicted of any crime—with compassion and dignity.

But there are major flaws in the city’s plan. The construction of four new jails in dense urban neighborhoods, at enormous expense and risk to the city’s fiscal health, does not guarantee inmates the better care that the city has promised. By concentrating on location rather than on deeper-seated problems, the city may simply replicate Rikers’ problems elsewhere. Indeed, should the city fail to successfully execute its borough-based jails plan, it would even fall short of its ultimate, symbolic goal: closing Rikers.

The coronavirus crisis puts these flaws into sharper relief. At present, the city faces the loss of hundreds of thousands of jobs, billions—if not tens of billions—in tax revenue, and significant uncertainty over when recovery will begin and how strong it will be. As a result, New York simply has far less room for error than it did last fall, when it approved its plan to build new jails.

There is a better alternative: rebuild Rikers. This 400-acre island is an optimal location for multiple, welldesigned, low- to mid-rise jail facilities. Rikers is also New York’s only remaining open space near enough to the courthouses in all five boroughs to be a practical location for housing inmates in a sprawling setting—but far away enough from the general population to serve as a secure location. Figure 1 is a sketch of what a rebuilt Rikers Island might look like.

New York could turn Rikers’ fabled isolation into an advantage, rather than a disadvantage. The island’s geography presents an opportunity to experiment with giving inmates more freedom and flexibility than they could hope to experience in four new high-rise borough jails.

The Borough-Based Jails Plan: A Brief Overview

The ultimate goal of the new “borough-based jails plan,” according to the city, is “modern,” “humane” jails that are “smaller, safer, and fairer.”[1] Before Covid-19 spread, New York City’s jails, the majority of them on Rikers Island, were the home, at any given time, to nearly 6,000 daily inmates.[2] Most inmates are awaiting trial; that is, they are charged with, but not convicted of, a crime, and they cannot make bail or are not eligible for bail.

Rikers has long been a symbol of poor incarceration practices. Many of the island’s collection of nine low-rise jail facilities are outdated and poorly maintained. They lack basic provisions for personal hygiene and public health, forcing inmates to share toilets, for example. They also lack modern temperature controls, endangering the health and lives of inmates sensitive to heat or cold.[3] Such public-health deficiencies are even more urgent in the current pandemic, as corrections workers and inmates have tested positive for Covid-19. Indeed, the city has released nearly one thousand older and unhealthy inmates to protect their health.[4]

There are other problems. Cells and hallways are noisy and smelly.[5] Violence is prevalent: between 2008 and 2017, the city’s Department of Correction reported a doubling of inmate injuries, from 15,620 to 31,368, even as the inmate population declined 32%.[6] Deteriorating facilities and violence go together, as inmates are reported to have chipped off pieces of the decaying infrastructure to create weapons. Visitors have a difficult time coming to see inmates, as public transportation to the island is scarce. Once on the island, visitors must endure multiple security checks and additional bus rides from a central intake area to each jail facility, requiring more waiting.

To address the many long-standing deficiencies of Rikers Island, the mayor and the city council, in October 2019, approved a plan to build four new jails across New York City by 2026.[7] If all goes as planned, the city’s jail population would have fallen by more than half, making jails “smaller.” A better design would discourage violence, making jails “safer.” Jails would be located nearer to inmates’ homes, families, and friends, facilitating easier visits. Jails would also be closer to courts, helping to speed up the process between arraignment and trial outcome. The jails would offer outdoor space, natural sunlight, superior medical and mental-health care, and education, thus making the jails “fairer.”

The basic specifications for each jail[8] are as follows, although these deadlines are already subject to change as the city grapples with its coronavirus response.[9]

Financial Risks of the Jails Plan: At What Cost to the City’s Capital Budget?

Since mid-March, the state and city have mandated public-health closures of entire swaths of the city’s economy, including most retail, restaurant, and personal- services businesses. These closures will soon cause a steep falloff in tax revenues, likely far worse than what New York experienced after 9/11 or the 2007–08 financial crisis. Safeguarding the city’s capital budget for critical infrastructure that can support its fragile tax base has thus become paramount. Building four new jails, however, is the single biggest capital-construction project that the city government has embarked upon in more than a half-century—and the project is supposed to be finished on an aggressive schedule of six and a half years from mid-2020. The city estimates that the four borough jails will cost $8.7 billion in total.[10]

Even if the city builds the jails on time and on budget, $8.7 billion is a significant portion of the city’s 10-year capital budget—that is, the city’s schedule for long-term investments in infrastructure such as bridge repairs and restorations, bus and bike lanes, sanitation facilities, school buildings, and subsidized housing. Money that goes to the four-borough jail program is money that could have gone to other critical needs, including rebuilding the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway or repairing the New York City Housing Authority properties.

A comparison between the mayor’s January 2019 capital- budget proposal for the next decade,[11] which did not include funding for the four borough jails, and the mayor’s April 2019 proposal,[12] which did include such funding, illustrates this point. In January 2019, the projected capital (infrastructure) budget for the city’s justice system was $5.2 billion. By April, the justice system’s projected capital budget was $13.7 billion, driven by an increase in the corrections budget from $1.8 billion to $10 billion. The justice system now accounts for 12% of the overall $117 billion capital budget over the next 10 years, up from 5%.

For as long as the city’s economy continued to grow, committing $8.7 billion to borough jails did not cut the total amount of money that the city has to pay for other long-term needs. With the pandemic, the city must inevitably rethink its capital-budget priorities so that one experimental project does not overwhelm the rest of the scarcer money available for critical infrastructure.

Construction Risks: Can the City Build the Jails on Time and on Budget?

Overseeing the design and construction of four new complex high-rise buildings in dense urban neighborhoods simultaneously in little more than half a decade is an extraordinary undertaking, especially for a city government unaccustomed to overseeing projects of such scope. It is also the city’s largest complex infrastructure project in modern history.

The schedule is even more aggressive than originally intended. In April 2019, the city moved the timeline for the completion of the jails by one year, from 2027 to 2026, without explaining why the scope of the plan supported such compression.[13]

New York’s underground Third Water Tunnel is the closest rival to the jails plan. It costs $6 billion but spans five decades.[14] The Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s $11.1 billion East Side Access project will bring Long Island Rail Road trains below Grand Central Station. It is now a nearly two-decades-long undertaking.[15]

The jails plan is similar in scope to the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey’s rebuilding of the World Trade Center—also a project involving complex highrise buildings with specific security needs. It took well more than a decade and cost $15 billion.[16] The East Side Access and World Trade Center projects, moreover, encountered significant cost and schedule overruns, despite their governing agencies’ greater experience in managing large-scale infrastructure projects.

New York City’s government regularly oversees contracts to rebuild roads and repair bridges, construct schools, and build sanitation and environmental-protection facilities. But it has little experience in overseeing the design and construction of four complex high-rise buildings in such a short time. As the city puts it, the project involves “complex construction on … severely constrained project site[s].”[17] Each jail must have a 100% reliable power source; three of the four facilities must include secure bridges or tunnels to adjacent or nearby court facilities in lower Manhattan, central Brooklyn, and central Queens.

New York City’s Department of Design and Construction, which will oversee the jails plan, has no experience in such a large-scale project and has performed poorly on smaller projects. The department, for instance, spent $41 million and a decade—well over the initial $30 million budget and 2017 deadline—to build a modest library in Queens’ Long Island City. Yet the facility has been sued for violating the Americans with Disabilities Act, the federal handicapped-accessibility law.[18]

“Design-build,” the framework through which the city will award contracts to build the four jails, theoretically reduces the risk of cost overruns to city taxpayers by holding winning bidders responsible for design and construction, thus alleviating discrepancies between the two. Yet in its initial bid documents, the city notes to potential bidders that it will “mitigat[e] the risk to the design-builder by providing for appropriate allowances, potential economic price adjustment provisions, and mitigating unknown subsurface conditions.” Agreeing to shoulder the cost of “economic price adjustment[s]” leaves the taxpayer open to unknown cost overruns.

Three of the jails will require extensive work just to prepare the sites. In Manhattan, the winning bidder must first demolish two existing nine- and 11-storey towers comprising more than half a million square feet. The demolition, in turn, requires asbestos mitigation. The Brooklyn and Queens sites require similar demolition and remediation. In the Bronx, the city must first determine where to relocate the NYPD’s existing “tow pound”—where hundreds of impounded vehicles are kept—before a contractor can begin construction.

Legal uncertainty puts additional pressure on the city’s already aggressive bidding and construction schedule. Community groups in the Bronx, Manhattan, and Queens,[19] for example, have filed suits in state court against the proposed jails for each of their respective boroughs, claiming that the city did not follow the proper procedure for approval of a change in land use. Even short-term delays caused by these legal proceedings will put additional pressure on the city to do more work in a shorter time frame, thus pushing up costs as contractors add extra shifts and overtime.

Operational Risks: Would Borough-Based Jails Solve Rikers’ Problems?

Even if the city completes the four jails on a reasonable schedule and budget, it may not solve Rikers’ existing problems. Success depends, above all else, on the city achieving a highly challenging feat: ensuring that the inmate population does not exceed the facilities’ significantly reduced capacity. The city must reduce inmate populations below today’s record-low levels, or the jails will not function as designed. If the city cannot reduce the jail population, operating close to, at, or above capacity would imperil its ability to safeguard inmates’ health.

As of late 2019, the average daily population in the city’s jails was 7,365 inmates; by early 2020, the population had fallen to 5,721, the first time it had fallen below 6,000 in decades. (In addition to Rikers, the city has two smaller jails in Brooklyn and Manhattan, and a floating jail barge near the Bronx; all three would close as part of the four-borough jail plan, and the inmates would be transferred to the new facilities in Brooklyn and Manhattan.)[20] The four new jails will have a cumulative capacity of just 3,544 beds.

The city arrived at this number politically. The mayor’s office needed the city council member in each neighborhood to vote for a new jail and had to repeatedly reduce the number of beds to get each council member to sign on.[21] In 2017, however, when the city began to explore reducing its jail capacity, the report that it commissioned concluded “that it is possible to reduce the jail population to less than 5,000 people over the next decade.”[22]

But the city has never explained how it abruptly arrived at a maximum figure of 3,544 inmates rather than 5,000. To keep inmates below this new capacity, the city must reduce the current average daily number of inmates to its projected goal of 3,300 inmates[23] within seven years, a 42% decrease.

New York City’s jail population has declined from a high of nearly 22,000 inmates on an average day in 1991.[24] And over the past seven years, from 2012 to 2019, the jail population declined by 45%. New York today has a low rate of incarceration: 97 inmates per 100,000 adults, compared with 241 in Los Angeles and 450 in Philadelphia.[25]

Unless crime falls significantly from today’s near record-low levels, the city will have a difficult time achieving its far more aggressive goal without endangering public safety. Of the city’s mid-2019 average daily population in jail, 3,261 people were there awaiting trial for a violent felony, and another 901 were serving a short sentence. Even under pressure to allow nonviolent inmates to leave jail in order to reduce the risk of spreading coronavirus, New York could come up with only 1,500 of candidates, not thousands, leaving the population just below 4,000, or above the planned capacity of the new jails, and only by making dubious decisions such as releasing an inmate awaiting trial for allegedly murdering his girlfriend.[26] Reducing the population, then, even to today’s population of the most violent of the alleged offenders, and people already sentenced, would still leave the new jails above capacity.[27]

If the city cannot safely reduce the inmate population to match the capacity of its new jails, it will face two unpalatable options: running overcrowded jails or keeping obsolete facilities on Rikers open. Overcrowded jails would endanger the city’s stated goal of creating a more humane environment; it would, for example, endanger the city’s goal to reduce violence among inmates. In short, falling back on Rikers in 2026 would represent a failure to deliver on its multibillion-dollar promise. Yet the city has quietly left itself this option; the city council has not yet rezoned Rikers to prohibit jails there.[28]

There are other operational risks to the promises that the new high-rise jails will be safer and fairer. For instance, the government has never explained how it would evacuate hundreds of inmates onto crowded New York City streets in a fire or other emergency. As for the danger that inmates pose to one another (and to guards): though the city has projected operational savings from its potential reduction in inmates, having to secure each floor of a high-rise jail—rather than one large, open space across a horizontal corridor—likely will require more corrections officers per inmate, not fewer.

The city’s conception for new jails is that of small, apartment-style housing units (one inmate per unit, with a private bathroom and shower) surrounding a common area on each floor, a big contrast from today’s communal cells, where up to dozens of people can share a toilet.[29] Yet the city has never explained how guards might respond quickly to a disturbance on any one floor, or how guards might transport inmates by elevator from one floor to another without the risk that inmates might encounter fellow inmates from rival gangs. Even in modern jails, efforts at privacy and dignity may require more supervision, not less. A private bathroom and shower may be a noble goal, but a guard must be on hand to ensure that no inmate is spending a potentially dangerous amount of time by himself in such a private space.

In light of the problems revealed by the current pandemic, New York must also consider the heightened public-health implications of dispersed jails in dense neighborhoods. Corrections officers who interact with an institutional population that is, by definition, at greater risk of infection would be going to and from work in populous areas, possibly by public transit, rather than driving to and from a secured island.

The city also faces significant challenges in being able to offer ample recreational, outdoor, therapeutic, and medical spaces within high-rise configurations. The existing Rikers Island jails offer supervised inmate access to a modest outdoor farm. It will be hard to re-create such an opportunity on the roof of a high-rise building, especially with security and power needs competing for space on that roof.

The New Borough Jails: Transportation

Rikers Island has two transportation problems: moving inmates to and from court; and encouraging family members and friends to visit inmates. Four-borough jails do not automatically solve either of these problems.

One motive behind the four-borough jail plan is to locate jails nearer courts, ensuring easier travel time from Rikers to the rest of the criminal-justice system. The new Bronx jail, however, will be two miles from the Bronx Criminal Court. At the other three jails, there is no guarantee that any given inmate will find himself incarcerated near the court that is relevant to his case. The four jails divide inmate capacity equally, but the distribution of inmates jailed before trial is not equal by borough. A recent survey of inmates found that 32.1% of the average daily population had been arraigned in Manhattan, for example. Only 15.1% were arraigned in the Bronx (Figure 2).

If the new jails operate at or above capacity, the unequal distribution of inmates by borough will require the transfer of some inmates to a jail not near the courthouse where their case will take place. If Manhattan continues to detain a disproportionate number of inmates, for example, inmates awaiting a court date will have to await their trial in a Bronx or Queens jail. (Inmates awaiting a Staten Island Court date will face incarceration in the Brooklyn jail.)[30]

If the new jails operate at or above capacity, the unequal distribution of inmates by borough will require the transfer of some inmates to a jail not near the courthouse where their case will take place. If Manhattan continues to detain a disproportionate number of inmates, for example, inmates awaiting a court date will have to await their trial in a Bronx or Queens jail. (Inmates awaiting a Staten Island Court date will face incarceration in the Brooklyn jail.)[30]

Dividing the inmate population equally by borough ignores another issue: crime and incarceration rates are not distributed equally by borough, nor do offenders necessarily commit a crime in their home borough. The Bronx, for example, has the highest incarceration rate, proportionate to population, among the five boroughs.[31] An inmate from the Bronx who had allegedly committed a crime in Brooklyn could find himself detained in Queens, making it difficult for family and friends to visit.

Another Way: A Reimagined Rikers

As the city notes, its new jails must be a successful example of an “enduring design that supports justice reform for many decades to come.”[32] In that spirit— and before committing irrevocably to spending billions of dollars in taxpayer money on a flawed plan—the city council and mayor should pause the current bid process and consider an alternative: rebuilding Rikers as a modern jail.

To be sure, the city should demolish Rikers’ existing jail buildings. But it can do so one by one, taking advantage of the fact that Rikers is at only 60% of its capacity. The city can rebuild a jail campus in place and transfer inmates from old to new facilities as each new facility opens, thus avoiding a high-pressure deadline.

By rebuilding Rikers, New York can avoid significant risks posed by the borough jails plan:

- the risk that the cost of four new jails will overwhelm the rest of the city’s capital-investment priorities after the coronavirus pandemic;

- the risk that the city cannot complete the project on time, on budget, and to stated specifications; and

- the risk that the jails will not have enough capacity for the inmate population.

Finally, New York can avoid the most significant risk of all: that shortfalls in achieving the goals of the borough jails would force the city to return to Rikers’ current outdated, deficient buildings to house an overflow of inmates. Indeed, as coronavirus hit Rikers, the city was forced to reopen a previously shuttered jail on the island to keep inmates spaced farther apart.[33]

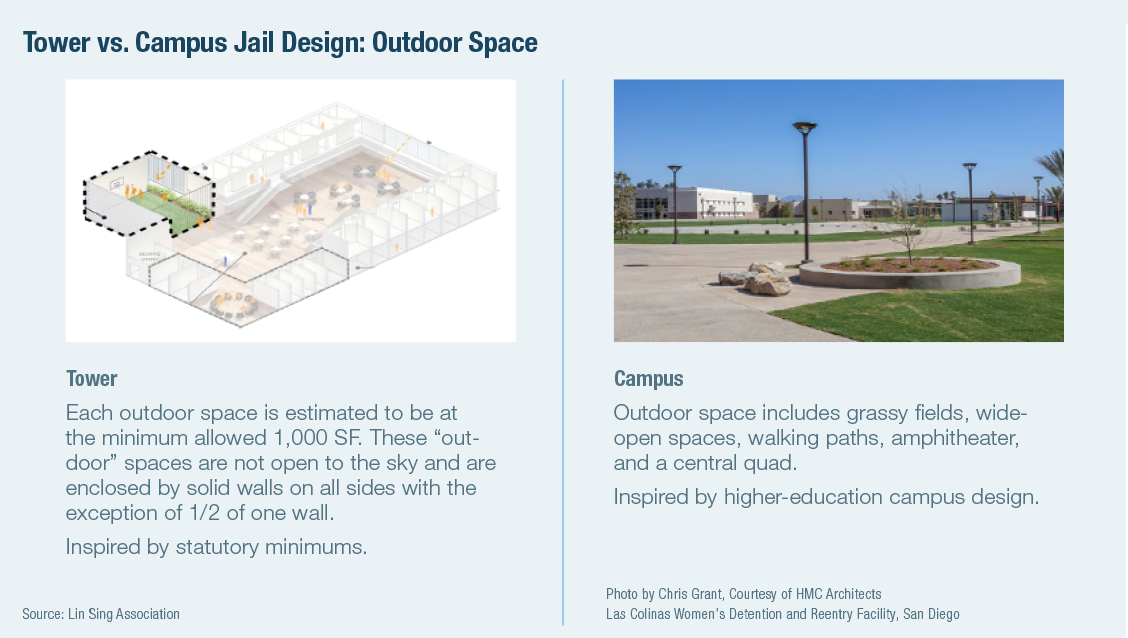

Bill Bialosky, a New York City architect, suggests a rough prototype. Working in collaboration with the Lin Sing Association, a Chinese-American advocacy group in lower Manhattan (which opposes a nearby neighborhood jail), Bialosky has concluded that a revamped Rikers would be far superior to four high-rise jails because the “campus” model for jails, just as it is for schools, is far superior to the “tower” model (Figure 3). He has drawn up a preliminary sketch (Figure 1) to illustrate the possibilities for Rikers as well. In fact, the jails and prisons that city officials visited as models for New York’s borough-based plans are campus-style jails, not high-rises.[34]

Examples of successful, modern, low- to mid-rise jails, by contrast, include the Van Cise–Simonet Detention Center in Denver (completed in 2010) and San Diego’s Las Colinas Women’s Detention and Reentry Facility (completed in 2014).

At Van Cise (Figure 4), inmates stay in dormitory-style housing that features natural lighting and spontaneous recreation opportunities.[35] Inmates can walk to decentralized medical clinics as well as therapeutic and recreational activities.

At Las Colinas (Figure 5), separate facilities house different functions, from sleeping to eating to recreation and education, with inmates getting outdoor exercise as guards escort them among facilities. The jail’s architects and designers paid attention to light and acoustics to create an environment to soothe, not agitate, detained individuals.[36]

Yet both these facilities are low-rise; the taller of the two, Van Cise, is five storeys.

For safety, new jails on Rikers would also offer better options than high-rise towers in dense urban neighborhoods, such as a need for evacuation to secure refuge points in the case of fire or other danger. Similarly, visitors to new jails would have ample room and time to go through well-staffed security entrances equipped with modern contraband-detection machines. As for fairness: new jails could offer far more natural outdoor space for recreation and therapy, including farming and animal husbandry, than can indoor high-rise spaces.

Finally, though the city’s goal to reduce its inmate population is noble, it could rebuild a new Rikers Island with extra capacity, ensuring that new jails are not overcrowded and not harming inmates’ quality of life and public-health outlook.

A Reimagined Rikers: Financial Benefits

Rebuilding Rikers Island could achieve significant cost savings compared with building four separate new jails. Material and labor costs will be the same. However, the city could save on the logistical costs of setting up four separate construction sites in four separate dense urban neighborhoods—which makes everything from pouring concrete to accepting delivery of rebar more difficult.[37] These overhead costs generally constitute 20% of a large project, or nearly $2 billion; saving 20% on this portion of the project, in turn, would yield savings of over $300 million. Moreover, in building on Rikers, the city would have more deadline flexibility. It could simply transfer inmates from an older facility to a newer one as each building opens, without having to scramble to meet the current drop-dead symbolic goal of closing Rikers.

In addition, eventually, the city could sell the Manhattan and Brooklyn jail sites to developers for midrise market-rate housing, earning a profit that it could invest in a rebuilt Rikers. The Queens and Bronx sites are good candidates for below-market, working-class and middle-class housing, though such projects would likely require subsidy. In fact, the city had once considered the Bronx site for such “affordable” housing.[38]

A Reimagined Rikers: What About the Drawbacks?

Rebuilding Rikers requires upgrading the inadequate transportation services for visitors. It also requires environmental remediation. Neither hurdle is insurmountable— and the city must address them, anyway, in whatever it decides to build at Rikers when it no longer uses the island for jails.

There are two ways to solve the current challenges faced by visitors to Rikers. First, to supplement the MTA bus, which provides service from Queens every 12 minutes,[39] the city can provide more frequent free shuttle service from Harlem and Brooklyn, increasing the service from its current 45–60-minute waits.[40] The existing bus service to Rikers costs the city $1.6 million annually; expanding this service would be a negligible expense, compared with building four borough jails.[41]

More ambitiously, the city could integrate Rikers Island into its five-borough fast-ferry system. As architect Bialosky points out, ferries to Rikers from Astoria in Queens and Soundview in the Bronx would provide far faster access than does current mass transportation. The city currently spends $60 million annually to subsidize its existing six-route ferry system; adding a limited route to Rikers likely would cost in the low tens of millions of dollars annually, including the cost of debt on the initial construction of a pier.[42]

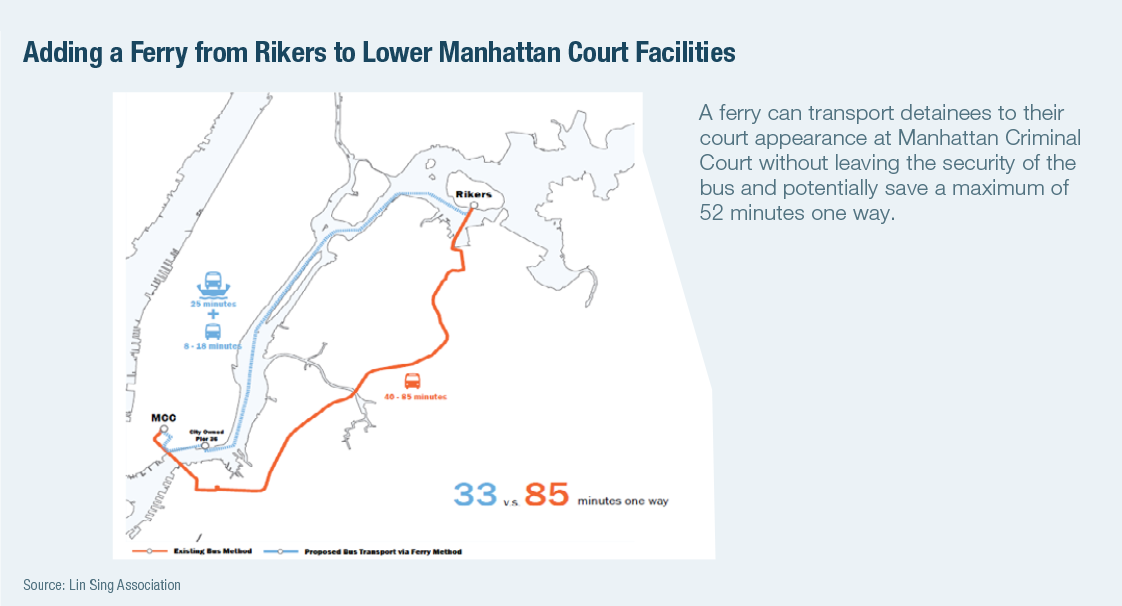

Ferries could also provide the city with a better way to transport inmates to and from Manhattan Criminal Court (Figure 6). A ferry from Rikers to lower Manhattan court facilities could “transport detainees to their court appearance[s],” says Bialosky, “without leaving the security of the bus.” He adds that it might save “52 minutes one way.” Similar ferry service to Rikers from Brooklyn, Queens, or the Bronx could cut inmate-commute trips, as well.

Further, as the city remakes its street space to provide priority access to MTA buses, it can integrate buses to and from Rikers in bus-only lanes along major thoroughfares across the boroughs.

The second major hurdle that the city faces in reimagining Rikers is environmental remediation. Rikers is built on landfill, which emits noxious methane gas.[43] The island also requires flood protection. The city has never comprehensively cataloged Rikers’ environmental challenges, or estimated the cost required to address them. Yet environmental remediation and flood protection are likely prerequisites for many other future uses of Rikers Island and, here again, the costs are likely less than those associated with borough-based jails.

Conclusion

New York’s four-borough jails plan would require significant taxpayer investment and government competence to execute on time and on budget. Yet executing this plan exactly as laid out may not even pay off, in terms of helping the city achieve its goals of smaller, safer, and fairer jails. There is no guarantee that smaller jails in Brooklyn, the Bronx, Manhattan, and Queens, built in constricted highrise environments, can successfully provide ample outdoor space or ample therapeutic space. There is no guarantee that high-rise jails can provide visitors with a better, faster experience in overcoming transportation and security hurdles. Should the jails ever exceed their 3,300-inmate capacity on a sustained basis, overcrowding would make it even harder to achieve the goals of safety and fairness.

No one disputes that the existing Rikers facilities need razing. Before awarding multibillion-dollar designand- build contracts that put the city on a path of no return, though, the mayor and city council should halt this process. It is not too late. The city’s Department of Design and Construction does not anticipate awarding a contract for the first two jails, in Manhattan and the Bronx, until September and November 2021, respectively.[44] The city should use this time to invite architects and developers to propose their own visions of what a reimagined Rikers could look like.

Opening these new jails would, in turn, allow the city to achieve another stated aim: the closure of all existing, obsolete jails on Rikers Island. Rikers, for more than eight decades the site of most of the city’s incarceration facilities, is now shorthand for failure. “Obviously, we’re going to get off Rikers Island,” the mayor said last year, in response to the news that an inmate there had attempted to hang himself. “We get out of Rikers, and we get into the kind of facilities that are modern.”[45] But why not stay on Rikers, and accomplish the same goal, transforming Rikers from failure to success?

Endnotes

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).