Will Employers Stop Offering Health Insurance? Expanded ACA Subsidies Leave Most Workers Better Off if They Do

Executive Summary

Congress is considering renewing an expansion of the Advance Premium Tax Credit (APTC), which provides federal subsidies for households to buy health insurance from the individual market.

Individuals are ineligible for APTC subsidies if their employers offer them tax-exempt health-insurance benefits. Without expanded subsidies, most workers are better off if they are offered employer-sponsored insurance (ESI). With expanded subsidies, they’re better off if they are not.

The average value of APTC subsidies was originally designed to be worth 5% less to workers than the ESI tax exemption, in order to maintain incentives for employers to provide health-care benefits. But the expanded subsidies average 65% more than the value of the ESI tax exemption. If all employers stopped offering health-care coverage to workers, to allow them to claim these expanded subsidies, it would increase the cost to the federal budget by $250 billion per year.

ESI Tax Exemption

The employer-sponsored insurance (ESI) tax exemption has made employers the main purchasers of health insurance for American workers and their families. Employers can avoid taxes of up to 54% by compensating workers—as well as their spouses and dependent children—with health-insurance benefits rather than cash.[1] As a result, 89% of privately financed health insurance was purchased by employers in 2023.[2]

The ESI tax exemption has long appealed to politicians of both parties. In the three decades following World War II, it encouraged the rapid expansion of health-insurance coverage to 70% of non-elderly Americans.[3] This protected millions of Americans from financial disaster associated with illness, improved their access to health care, and helped finance the expansion and development of medical facilities—all without increasing the cost of government, creating disincentives to work, or politicizing the details of medical payment.[4] Legislators saw tax preferences as a cheaper alternative to full public financing of regressive insurance benefits.[5]

But relying on employers to purchase health insurance also has disadvantages.[6] It imposes one-size-fits-all benefits on all workers, which are unresponsive to individual needs.[7] This makes benefits needlessly costly, causing wage compensation to stagnate.[8] ESI also gives employers responsibilities for which they are poorly suited and exposes them to risks that they have little ability to control—which is especially burdensome for small employers. Furthermore, it can leave families uncovered whenever their breadwinners lack stable employment.

Exchange Subsidies

The Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA) established federal subsidies for low- and middle-income households to purchase health-insurance plans from the individual market. Lawfully present households are entitled to receive the Advance Premium Tax Credit (APTC) if they lack eligibility for other federal health-care entitlements or an offer of comprehensive employer-sponsored health insurance that is “affordable” (i.e., with premiums less than 9.02% of household income in 2025).[9]

APTC subsidies can be used to purchase health-insurance plans from ACA’s exchanges. Insurers are generally required to sell each exchange plan to everyone who wishes to enroll within a geographic area at the same price, regardless of their health status. Plans are only permitted to adjust premiums according to age (by up to a 3-to-1 ratio), by family size (up to three children), and according to tobacco use (by up to 50%).

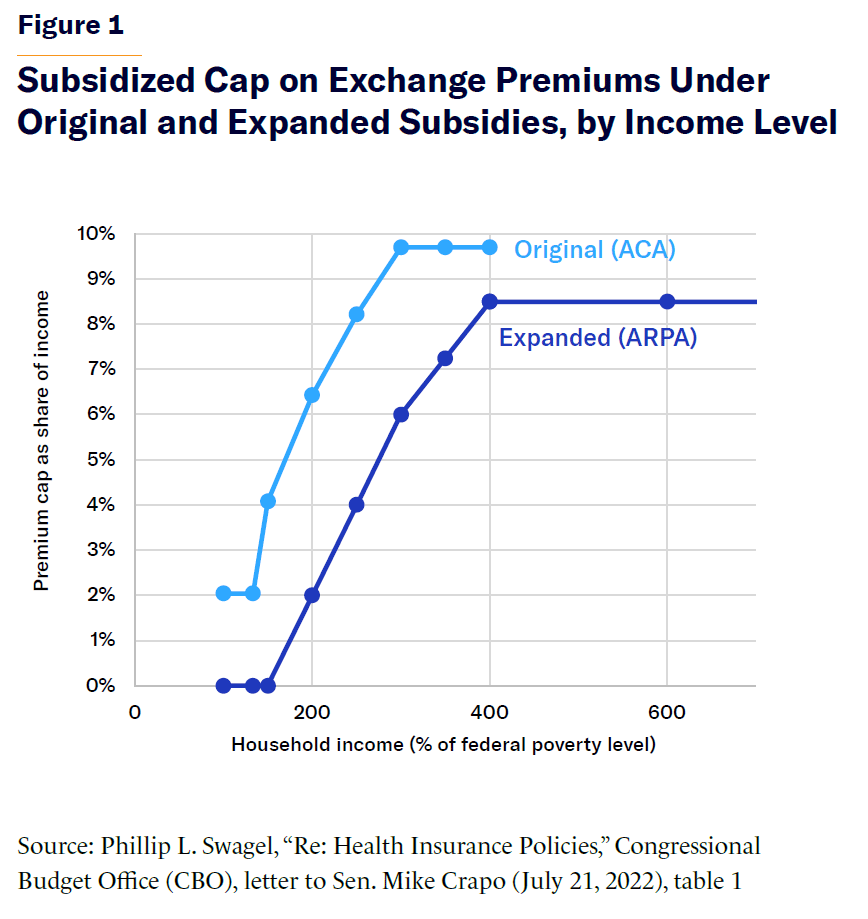

Under the original ACA, eligibility for APTC is limited to households with incomes between one and four times the federal poverty level ($15,960–$63,840 for a household of one; $33,000–$132,000 for a household of four, in 2026).[10] These subsidies expand automatically as necessary to limit the cost of benchmark premiums as a share of each household’s income (Figure 1).

The American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (ARPA) expanded APTC eligibility to households with incomes greater than four times the federal poverty level. It also increased the magnitude of APTC subsidies, by reducing the limit on post-subsidy premiums, defined as a proportion of household income (Figure 1). In 2022, the Inflation Reduction Act extended the APTC expansion until the end of 2025.

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has estimated that permanent APTC expansion would increase the number of beneficiaries by 4.8 million, while reducing ESI enrollment by 2.3 million, as employers stopped offering health-insurance benefits to employees. CBO projects that this would indirectly increase Medicaid enrollment by 0.2 million.[11]

As a result, CBO estimates that permanent APTC expansion would increase the cost of the subsidies to the federal budget by 20% ($23 billion in 2026), even after accounting for increased tax revenues from reduced provision of tax-exempt ESI.[12] But CBO has greatly underestimated the impact that the expansion of APTC subsidies would have on decisions by employers to offer health-insurance benefits to their workers—and therefore the overall cost of expansion may be many times larger.

Incentives to Abandon Employer Coverage

If APTC subsidies exceed the value of the ESI tax exemption, workers and their dependents may be better off if their employers do not offer them affordable ESI.[13]

To prevent this from happening, the ACA established an “employer mandate” penalty ($2,970 per worker in 2024, indexed for inflation) for employers with 50 or more workers who do not offer affordable health insurance to their staff.[14] But the penalty provides no incentive for employers to provide coverage for the spouses and children of employees.[15] The penalty also does not apply to small businesses or federal, state, and local governments.[16]

For low-wage workers, even the original ACA subsidies were worth more than the value of the ESI tax exemption. However, most workers who are offered ESI have higher incomes, so in most cases the ESI tax exemption was worth more than the APTC subsidies.[17]

Furthermore, the ACA’s reforms greatly degraded the appeal of plans on the individual market: premiums more than doubled, deductibles soared, provider networks narrowed, and many insurers abandoned the marketplace altogether.[18] For most workers, ESI coverage remained cheaper than even subsidized exchange plans.[19] Due to disappointing enrollment in the individual market and the establishment of a penalty on employers that failed to offer ESI, the net effect of ACA was initially to increase the proportion of workers offered ESI by 5%.[20]

Nor did the ACA’s expansion of Medicaid to low-income able-bodied adults deter employers from offering ESI to workers.[21] Medicaid-eligible employees can decline an offer of ESI and enroll in Medicaid to get coverage that doesn’t require premiums or out-of-pocket costs. To some extent, this could incentivize employers to offer ESI, since it makes it cheaper for employers to offer ESI, if they know that many low-paid workers may not enroll. Nonetheless, Medicaid expansion led to a substantial crowd-out of ESI enrollment, with 56% of workers newly enrolled in the program having previously been covered by ESI.[22]

ARPA has substantially altered the situation by greatly increasing APTC subsidies and eliminating the associated means test. As a result, APTC subsidies became potentially appealing for the bulk of full-time and securely employed middle-class workers, who were previously most likely to have been offered ESI. From 2014 to 2024, subsidized individual market enrollment increased from 6 million to 21 million, even as unsubsidized enrollment declined from 8 million to 2 million.[23]

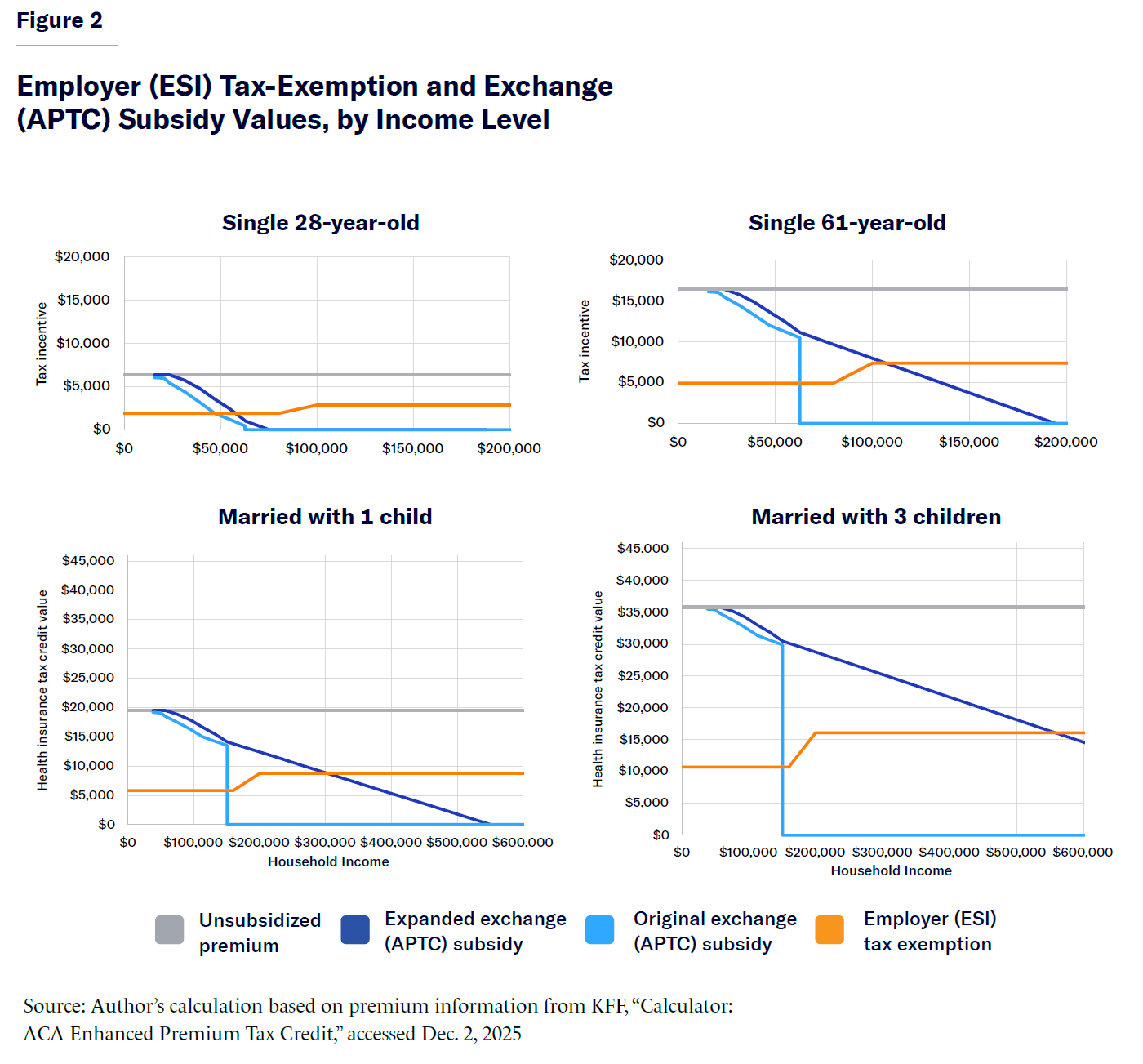

In particular, ARPA greatly increased the relative magnitude of APTC subsidies for higher-income households with the costliest insurance (Figure 2).

ARPA raised the break-even point at which the value of APTC exchange subsidies exceeds that of the ESI tax exemption:

- For a single 28-year-old, from $47,000 to $58,000

- For a single 61-year-old, from $63,000 to $115,000

- For married parents (both aged 40) with one child (aged 10), from $150,000 to $300,000

- For married parents (both aged 50) with three children (aged 18, 16, and 14), from $150,000 to $550,000

Using statutory rules for APTC subsidies, marginal tax rates, census survey data on household incomes, and reported national unsubsidized health-insurance premiums, it is possible to estimate the value of the ESI tax exemption and APTC subsidies (original and expanded) for a representative sample of the non-elderly American population.[24]

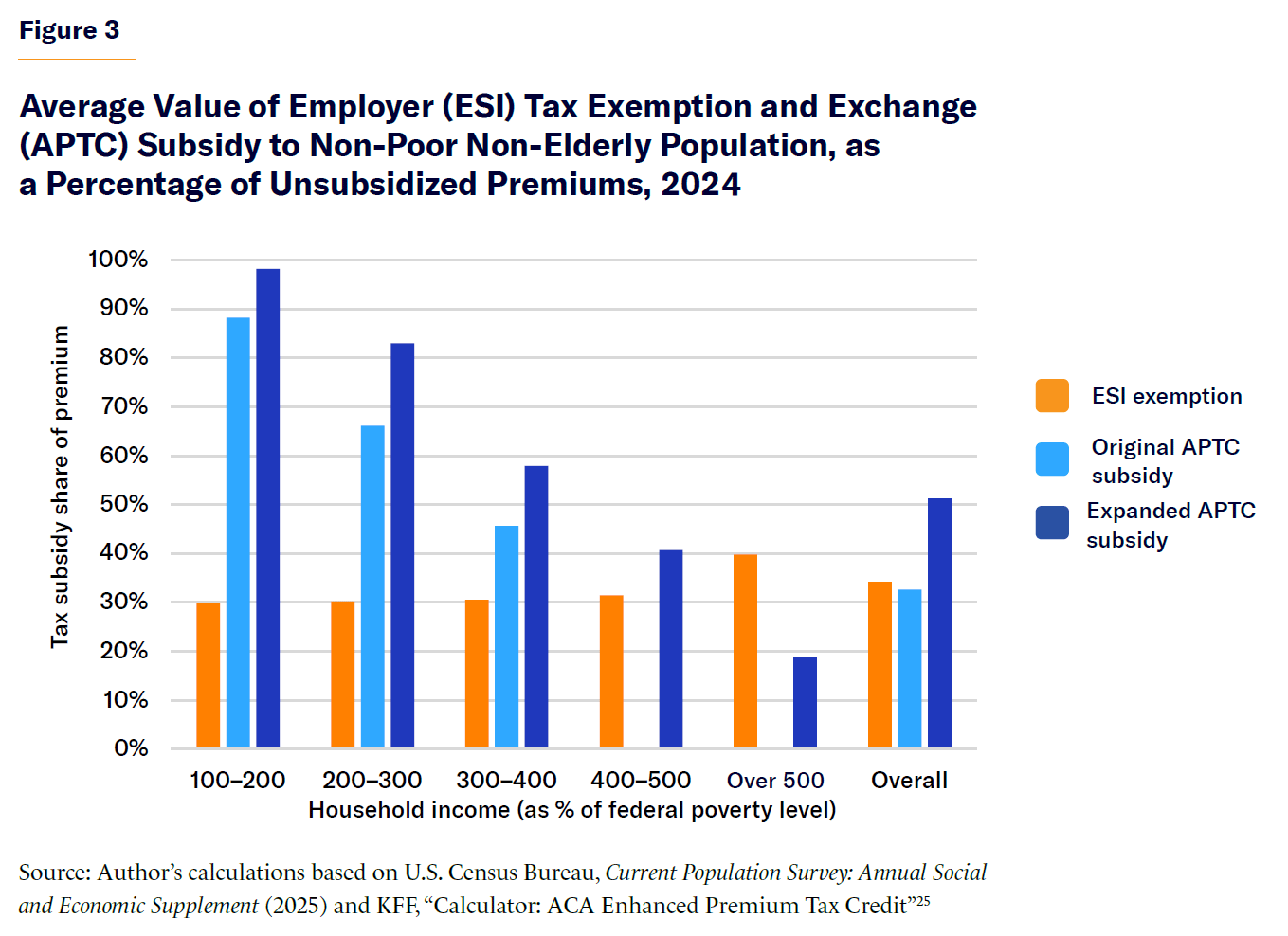

The expansion of APTC subsidies greatly increases the federal subsidy as a proportion of health-insurance premiums for the non-elderly non-poor population from 33% to 51% (Figure 3). That increases the average value to workers of APTC subsidies from 5% less than the average value of the ESI tax exemption, to 65% more.

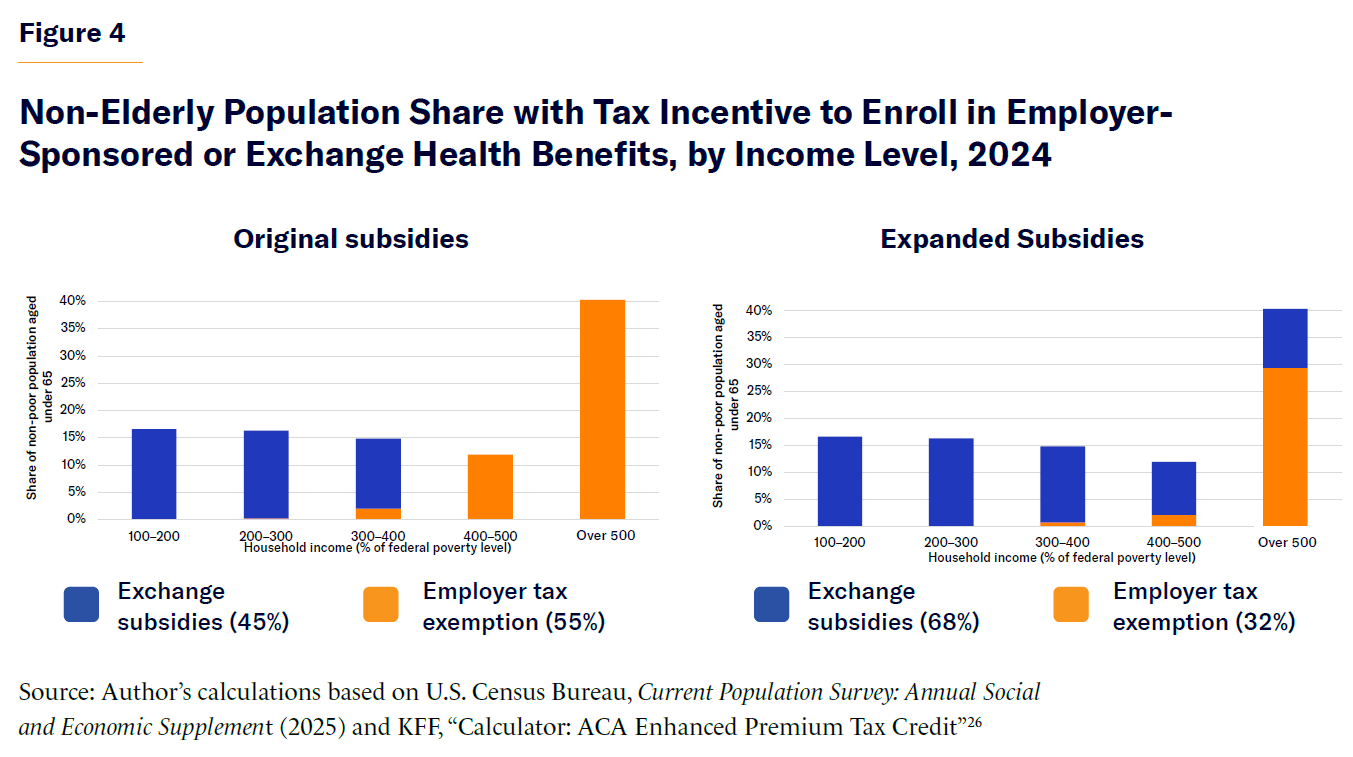

With APTC expansion, the subsidies would be worth more than the ESI tax exemption for 68% of non-elderly Americans in non-poor households in 2024; without expansion, subsidies exceed ESI for only 45% of workers in such households (Figure 4). As a result, the majority of workers would be better off if their employers did not offer them health insurance. Among those for whom the ESI exemption remains more valuable than expanded APTC, expansion decreases the median difference in the value between the two, from $5,391 (without expansion) to $3,372 (with expansion).

The appeal of employer-sponsored insurance has been further diminished by the relative reduction of premiums for equivalent unsubsidized coverage on the exchanges. In 2018, the average ESI plan ($6,896) cost only slightly more than gold plans on the exchange ($6,312); in 2025, ESI plans cost significantly more ($9,325 for ESI vs. $6,084 for gold).[27] The difference between the two is now greater than the penalty for large employers that fail to offer health-insurance coverage to their workers.

For most covered by ESI, there is no employer mandate penalty to offset the growing relative appeal of coverage from the exchange. This is because the penalty applies to only 58 million of 268 million non-elderly Americans.[28] The penalty provides no incentive for businesses to offer coverage to spouses and children, and it does not apply to firms with fewer than 50 full-time employees or to the public sector. Businesses can also evade penalties by outsourcing employment to smaller firms.

Since ARPA increased APTC subsidies, there has already been a substantial decline in offers of ESI, concentrated among smaller employers. From 2019 to 2025, the share of firms with 10–49 workers offering ESI fell from 67% to 54%; for firms with 50 or more workers, that share declined from 94% to 91%.[29]

CBO has suggested that a permanent expansion of APTC subsidies would lead to a larger decline in ESI coverage than ARPA’s temporary expansion because the “temporary nature of the enhanced subsidy” deterred employers from changing their “decision to offer health insurance.”[30] But any agreement to temporarily expand APTC subsidies beyond 2026, under the Republican-led 119th Congress, would likely be widely viewed as a signal of bipartisan support and a precedent equivalent to a de facto permanent expansion.

Implications

Several other factors may deter the elimination of ESI. Employers are likely to be wary of suddenly taking away benefits that workers cherish and rely upon. Workers are likely to dislike the prospect of changes in their access to care, being forced to shop around and enroll in exchange plans, and the poor reputation that these plans retain from ACA’s early years. Human resources staff would be unlikely to promote such a transition, as it threatens their own employment. But these factors would not exist for new businesses. For existing businesses, they may be gradually overcome if a switch from ESI to subsidized exchange coverage allows them to provide workers with substantially higher disposable incomes and better health-care benefits.

Attempts to eliminate ESI may also be impeded by heterogeneity in the circumstances of workers and their dependents. Employers cannot limit offers of benefits to workers for whom the value of the ESI tax exemption exceeds that of the APTC subsidy, because federal law restricts their ability to discriminate in offering ESI to some employees and not to others.[31] Furthermore, it may be hard for firms to identify which workers would benefit, since the value of APTC subsidies depends on spousal income levels, which may be unknown to employers offering health insurance. Workers who stand to lose from the elimination of ESI may therefore endeavor to impede any shift.

But employers could target the distribution of pay increases funded by the elimination of ESI to ensure that all workers profit from a switch. If the aggregate magnitude of APTC gains to all employees within a firm exceeds the aggregate magnitude of the ESI tax exemption forgone, businesses could make all workers better off by eliminating offers of ESI and increasing the wages of workers who suffer net losses. If such strategies are widely employed, ESI may become limited to firms with predominantly highly paid employees.

The fiscal cost of the widespread abandonment of ESI would be enormous. If the ESI tax exemption had been claimed by all non-elderly non-poor households in 2024, it would have averaged $6,379 per family. This exceeds the mean APTC subsidy that such households would have obtained under the original ACA ($6,086), but it falls well short of the enhanced APTC subsidy that they could have received post-ARPA ($10,046).[32] As the ESI tax exemption cost the federal government $384 billion in 2024, a comprehensive switch from ESI to exchange plans with APTC subsidies could cost the federal budget an additional $250 billion per year.[33] Costs to the federal budget may be further increased if the elimination of ESI coverage reduces incentives for marriage and employment.

The permanent expansion of APTC subsidies is likely to have a much more significant impact on offers of employer-sponsored health insurance than has been appreciated. Much is to be said for shifting control over the purchase of health insurance from employers to individual families; but it can and should be done without greatly increasing overall federal subsidies for the purchase of coverage.[34]

Endnotes

Photo: krisanapong detraphiphat / Moment via Getty Images

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).