Thinking Again About Midtown South NYC’s New Plan is a Mass of Contradictions

Introduction

One of the most rewarding aspects of being a city planner in New York City, as I was for 38 years, is participating in the stewardship of Midtown Manhattan, one of the most dynamic and exciting places in the world. Midtown is truly a globally significant economic and cultural resource, and the decisions that planners make can advance it to its next stage of greatness.

Ill-considered planning decisions, however, can impair Midtown’s dynamism and make it dull, ugly, and moribund. I was reminded of that as I reviewed the Midtown South Mixed-Use Plan recently proposed by the NYC Department of City Planning (NYC DCP).[1] The zoning changes implementing the plan began a roughly seven-month process of public review in January 2025. As a longtime, now-retired NYC DCP official, I applaud the plan’s goal of updating antiquated zoning and constructing large numbers of new housing units in Midtown. Unfortunately, the plan is seriously flawed due to contradictory policies imposed both by the city itself and by the state legislature. This brief explains in detail where the plan goes wrong and how it can be improved, as well as additional actions that the city should take to achieve its Midtown housing goals.

The Midtown South Mixed-Use Plan originated with a bill passed by the state legislature passed in April 2024. Between 1961 and 2024, the state Multiple Dwelling Law (MDL) capped the size of new residential buildings, even in Midtown Manhattan, at a floor area ratio (FAR) of 12.[2] The cap resulted from political bargaining, which led to the passage of the 1961 comprehensive revision to NYC’s Zoning Resolution. The city had long sought more flexibility to determine through local zoning how large residential buildings could be—the same flexibility it has for nonresidential buildings. In 2024, the legislature amended the MDL to allow new residential buildings to exceed 12 FAR, provided that such buildings comply with the provisions of the Mandatory Inclusionary Housing (MIH) program.[3] As a result, NYC DCP duly created two new zoning districts, R11 and R12, in which residential buildings could attain FARs of 15 and 18, respectively, with MIH compliance. These new districts were approved by the city council in December 2024 as part of the “City of Yes for Housing Opportunity” zoning amendment.[4] In the Midtown South Mixed-Use Plan zoning amendment, the new districts are mapped in four zones in and adjacent to Midtown Manhattan. These four areas are currently zoned for manufacturing and do not allow new housing, reflecting circa-1961 land-use conditions that have long since changed markedly.

This brief will: describe the four zones and the proposed new zoning; raise some concerns about the financial feasibility of MIH as proposed; discuss why the proposed zoning changes, even if financially feasible, may not represent good land-use planning; and make suggestions for how this proposed zoning should be modified by the City Planning Commission and the City Council.

Background and Proposal

The zoning plan affects four areas, referred to in project documents as Northwest, Northeast, Southwest, and Southeast (Figure 1). The four areas are all zoned for manufacturing but have varying histories.

Northwest Area

The Northwest Area is the core of the historic Garment Center. For several decades after the enactment of the city’s current zoning resolution in 1961, it remained a declining, but still active, location for apparel manufacturing and the front offices and showrooms of companies producing women’s apparel. Its current manufacturing zoning designation (M1-6, the same zoning district that is mapped in nearly all the other rezoning areas), allows 10 FAR for nonresidential uses, which can be increased to 12 through floor area bonuses for public amenities.

In 1984, the city and state approved the 42nd Street Redevelopment Project, an ultimately highly successful effort to upgrade the urban environment of Times Square and the crime-ridden block of 42nd Street between Times Square and 8th Avenue.[5] The International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union (ILGWU) asserted that upgrading Times Square and 42nd Street would make the buildings of the Garment Center, immediately to the south, valuable as office space, resulting in the involuntary displacement of apparel manufacturing firms. To gain the union’s support, the city agreed to create a special zoning district in the Garment Center that would restrict conversions of manufacturing space to office space.

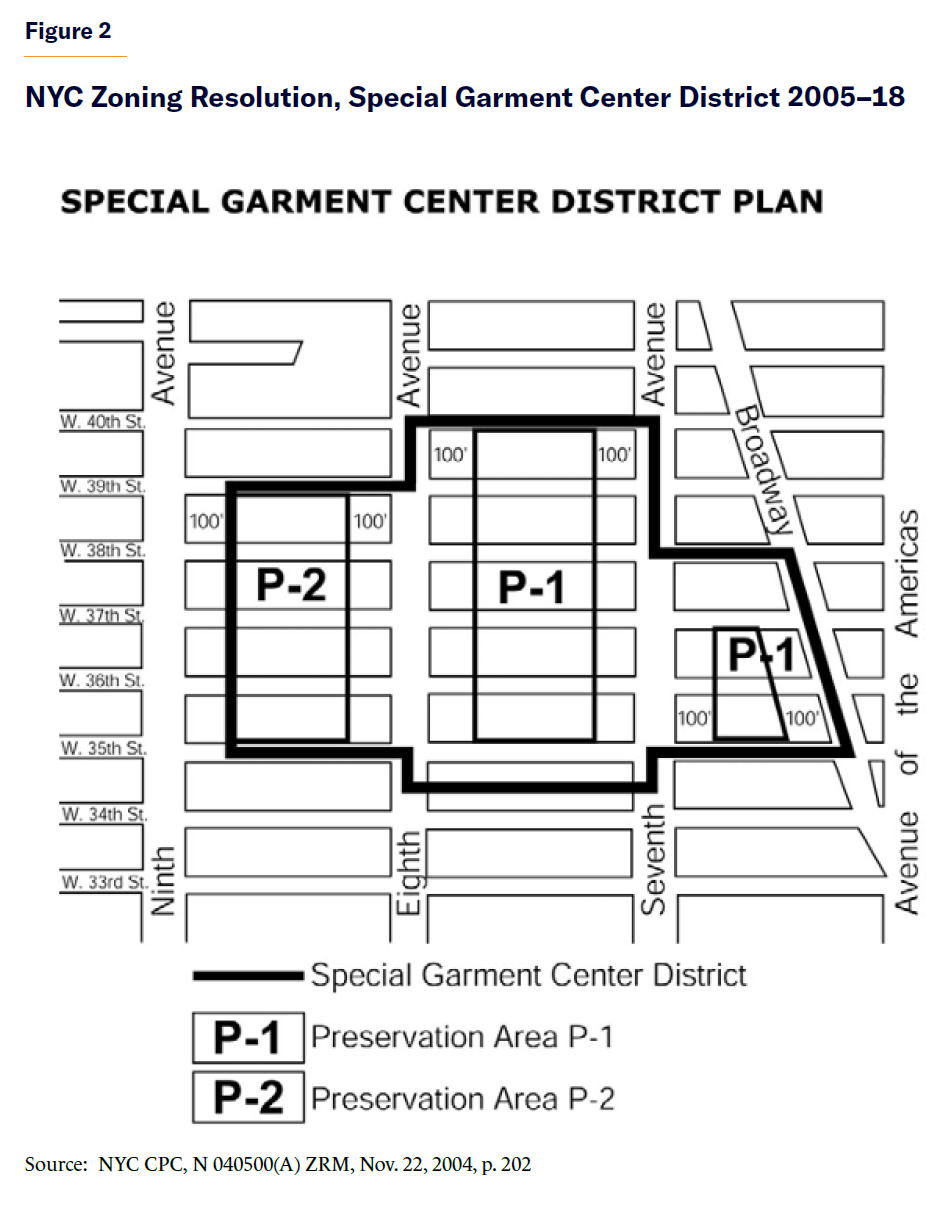

The Special Garment Center District (within the boundaries shown in Figure 2) was added to the city’s Zoning Resolution in 1987.[6] The special zoning district created “preservation” areas in the mid-blocks between Broadway and 9th Avenue, where most of the apparel manufacturing businesses were located. In these areas, manufacturing and showrooms were allowed, but new offices were not. In buildings fronting Broadway, 7th Avenue, and 8th Avenue, no new restrictions were imposed.

The new zoning was vehemently opposed by property owners and difficult to enforce, as the distinction between showrooms and offices was obscure. Over time, the proportion of supposedly “preserved” space used as offices rose steadily. The zoning was more successful in deterring upgrades to older manufacturing loft buildings, because it was impossible to obtain approval from NYC Department of Buildings for any improvements that would require a new certificate of occupancy as office space.

In 2005, the special district zoning was amended to allow new residential construction in the mid-blocks between 8th and 9th Avenues (renamed area P-2, shown in Figure 2), and residential conversion of smaller non-residential buildings. Residential conversions were not allowed, and existing restrictions on offices were maintained, for buildings over 70,000 sq. ft. in floor area.[7] The change resulted in significant development of new apartment buildings and hotels. The preservation areas east of 8th Avenue, which still had the 1987 rules, were renamed P-1.

In 2018, the office conversion restrictions were finally lifted in the P-1 and P-2 areas. The nomenclature of the district was changed, with Area P-2 becoming Area A-2 and the remainder of the special district becoming Area A-1. Special height and setback rules were applied to Area A-1 intended to ensure that new buildings would be compatible with surrounding loft buildings.[8] The upshot of decades of restrictive zoning and disinvestment in the areas other than P-2 is the substantial preservation of the area’s historic loft building stock. In 2008, in recognition of the area’s architectural consistency and notable history, the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation nominated the Garment Center Historic District to the National Register of Historic Places.[9] According to the nominating form:

The proposed Garment Center historic district is historically and architecturally a remarkable section of Manhattan which has no parallel anywhere else in the city or the country. Formed in large measure by political and economic forces—notably the effort to move the garment industry away from fashionable Fifth Avenue—and planning reforms—in particular, the 1811 Commissioners Plan laying out the street grid, the 1916 Zoning Resolution creating the typical set-back profile of the loft buildings, as well as reforms in garment industry practices and buildings resulting from the tragedy of the Triangle Building fire—the district encompasses a significant piece of the city’s and the country’s economic history, its immigrant history, and the development of vernacular commercial architecture in the years between the two world wars.[10]

The Northwest Area is entirely within the National Register historic district—which, unlike NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) historic districts, does not regulate development or prevent demolition of contributing buildings—but which does confer eligibility for federal Historic Preservation Tax Credits. The tax credits, in turn, facilitate rehabilitation of the historic loft buildings.

NYC DCP’s current Midtown South Mixed-Use Plan would rezone this area to permit new residential buildings at 18 FAR and commercial and community facility buildings at 15 FAR. Even larger buildings could be built, here and in the other three subareas, in exchange for providing space for a public school, creating a Covered Pedestrian Space, or making an improvement to a mass transit station. Conversions of existing non-residential buildings to residences would also be permitted. Any new residences would also be subject to MIH affordability requirements, and height and setback rules would be like those now applied in Special Garment Center District, Area A-1.[11] However, with more floor area allowed and no height limit, new buildings could be much taller. An illustrative graphic (Figure 3) provides an idea of how this might look on a typical Garment Center side street.

The zoning proposal includes two land swaps in which blocks are moved from one special district to another. The A-2 area in the Garment Center mid-blocks between 8th and 9th Avenues is moved into the Special Hudson Yards District, and the restriction on residential conversion of buildings over 70,000 sq. ft. is lifted. The southern half of the block bounded by 7th and 8th Avenues and West 40th and 41st Streets is moved from the Special Midtown District (Theater Subdistrict) to the Northwest Area. The half-block is occupied largely by the New York Times office tower on the 8th Avenue corner but also includes smaller buildings that might be redeveloped.

Northeast Area

The small Northeast Area exists because of political pushback by business, labor, and real-estate interests against the city’s efforts in the early 1980s to legalize nonresidential spaces occupied illegally as residential lofts. Mapping a manufacturing zone in place of the prior commercial zoning (which allowed residences), according to the City Planning Commission’s 1981 report, would “protect an additional 2.4 million square feet of apparel-related industrial space from residential conversion.”[12] The commission’s artful phrasing indicates that, even then, there was little manufacturing in the area.

The Northeast Area includes some older loft-type buildings, but they are not as predominant as they are in the Northwest Area. Hotels, mostly constructed in the past two decades, feature prominently. Many of these are “limited service” hotels, that is, without full-service restaurants or meeting space. During the mayoral administration of Bill de Blasio, the city effectively prohibited new construction of hotels at the behest of the Hotel Trades Council labor union, who wanted to suppress lower-priced competition for full-service union hotels.[13] The change left property owners in the area with few viable development options. In contrast, the frontages on 5th Ave and the Avenue of the Americas, which are mapped with commercial zoning at 15 FAR, have seen the development of large mixed-use buildings including commercial and residential space.

The Midtown South Mixed-Use Plan would have the same rules for new buildings and residential conversions as the Northwest Area. An illustrative graphic (Figure 4) provides an idea of how this might look on a typical Northeast Area side street.

Southwest Area

The Southwest Area consists of portions of blocks between Avenue of the Americas and 7th Avenue, which have had the same manufacturing zoning designation since 1961. In addition, the area includes most of the two blocks bounded by 7th and 8th Avenues and by West 28th and West 30th Streets. These two blocks are known historically as the Fur District, and they also include older loft-type buildings, similar to those in the Northwest and Northeast Areas, where fur apparel manufacturing and showrooms once predominated. With the decline of that industry, the city in 2011 rezoned the blocks to a mixed-use zoning designation called M1-6D, permitting new residential development at up to 12 FAR. Residential conversions were also allowed, but only in buildings with less than 40,000 sq. ft. in floor area, ensuring that the larger loft buildings would remain nonresidential.[14] Subsequently, several new residential buildings and hotels were constructed on the two blocks.

The blocks between Avenue of the Americas and 7th Avenue include a significant number of additional modern hotels, with two clusters along 28th Street and 24th and 25th Streets. Much of the remaining area is comprised of loft buildings, with larger buildings along Seventh Avenue and smaller buildings on the mid-blocks. Unlike the Northwest and Northeast Areas, there are a significant number of existing residences in the mid-blocks, mainly in converted buildings. Avenue of the Americas, outside the rezoning area, is lined with high-rise residential buildings.

The Midtown South Mixed-Use proposal would rezone the portion of the Southwest Area north of West 29th Street—parts of three city blocks—to 18 FAR residential and 15 non-residential, like the Northwest and Northeast Areas. The block west of 7th Avenue between West 28th and West 29th Streets would be rezoned to 18 FAR residential and 12 non-residential. The remaining blocks, east of 7th Avenue and south of West 29th Street, would be rezoned to 15 FAR residential and 12 non-residential. MIH would apply to new residential developments and conversions. Property owners in the two M1-6D blocks west of Seventh Avenue, where new residences are currently permitted, would effectively lose the ability to develop market-rate condominium buildings as-of-right. An example of such a building is the 87-unit Maverick at 215 West 28th Street.[15] An illustrative graphic (Figure 5) provides an idea of how this might look on a Southwest Area side street.

Southeast Area

Like the Southwest Area, the Southeast Area is comprised of manufacturing-zoned blocks that have not been rezoned since 1961. The area can be divided into distinct built contexts. South of West 28th St., the area is generally built with moderate-scale, historically non-residential buildings, some of which have been converted to residential use. Much of this area is within two NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC)-designated historic districts: Ladies’ Mile, between West 23rd and West 24th Streets; and Madison Square North, north of West. 26th St. The Ladies’ Mile historic district celebrates the architecture of the city’s 19th-century retail district.[16] Madison Square North, according to LPC,“consists of ... buildings representing the period of New York City’s commercial history from the 1870s to the 1930s, when this section prospered, first, as a major entertainment district of hotels, clubs, stores and apartment buildings, and then, as a mercantile district of high-rise office and loft structures.” [17]

North of West 28th St., west of Broadway, the built context is marked by high rise modern hotels: a 40-story building at the corner of West 28th St. and Broadway, and a 38-story building at West 29th St. and Broadway. East of Broadway, the Madison Square North historic district extends to West 29th St. Outside of the historic districts, the area is dense with individual landmarks: the Serbian Orthodox Cathedral of St. Sava between West 25th and West 26th Streets, the “Tin Pan Alley” buildings on the north side of West 28th St., a loft building, now residential, at 1200 Broadway (West 29th St.); and historic hotels at 1234 Broadway (31st St.) and 4 West 31st St. The landmarked Marble Collegiate Church at 270 5th Ave. is partly within the rezoning area, as is the Wilbraham apartment building at 284 5th Ave.

High-rise residential buildings flank the Southeast Area along Avenue of the Americas. Along Fifth Avenue, much of the frontage is protected from redevelopment by historic districts and individual landmarking. One of the few lots that is not, 262 Fifth Ave. at West 29th St., recently saw construction of a 54-story residential building.

The Midtown South Mixed-Use Plan would rezone the entire Southeast Area for 18 FAR residential and 12 non-residential. MIH would apply to new residential developments and conversions. An illustrative graphic (Figure 6) provides an idea of how this might look on a Southeast Area side street.

Issues with the Proposal

Economic Feasibility

The Midtown South Mixed-Use Plan proposes to rezone some of the most valuable land in the world to permit more housing, which is in high demand and commands premium rents and condominium sales prices. For example, The Capitol at 776 Avenue of the Americas is a 39-story, 387-unit rental building, built in 2001. It is located between the Southwest and Southeast Areas. According to the Streeteasy real-estate information website, in early February 2025, asking rents in the building were $3,978–$4,158 for studios, $4,762–$6,837 for 1-bedrooms, and $9,712–$9,887 for 2-bedrooms.[18] The Capitol’s annual property taxes are $8.8 million in 2025.[19]

With the potential for rents like these, real-estate developers would rush to invest in the rezoning area, were it not for an additional detail—the imposition of MIH, which effectively precludes condominium development and requires below-market rents for 25% to 30% of units. The theory of MIH is that rezonings confer an undeserved land-value windfall on property owners, some of which should be captured for a public benefit, for example, affordable housing. However, the de Blasio administration recognized that the cost of the affordability requirement far exceeded any windfall and that to induce developers to participate, the cost of MIH would need to be offset with public subsidy. Initially, the city negotiated with the state legislature to secure an extraordinarily generous long-term tax exemption for new buildings, known as Section 421-a, to offset the cost of providing affordable housing. Even with the tax exemption, MIH worked economically only for new rental buildings in the city’s strongest housing markets.[20]

The combination of MIH and 421-a likely would have worked economically for new rental buildings in the Midtown South Mixed-Use Plan rezoning areas. However, 421-a expired in June 2022, and its generous terms are no longer available. In 2024, the state legislature passed a new tax exemption known as 485-x, which is far less generous, especially for the large buildings likely to be produced at FARs of 15 or 18. The main difference is the imposition of “prevailing wage” requirements. Much of the net present value of the tax exemption, which offsets the cost of the below-market units, is effectively diverted to labor.[21]

Despite the reduction in offsetting tax benefits, NYC DCP has made no adjustment to MIH, nor has it offered any analysis indicating if and where the new tax exemption works economically. The risk that the subsidy might be inadequate is heightened by the post-pandemic rise in interest rates, as of early 2025, which makes both construction and permanent financing more expensive than was the case in the de Blasio years. The Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) for the Midtown South Mixed-Use Plan projects that, over a 10-year period after its adoption, it will result in the development of 8,949 housing units in new buildings, and 781 in converted non-residential buildings, for a total of 9,730 units.[22] That would be a significant increase for Manhattan, which once dominated NYC housing construction but, in recent years, has mostly lagged in new housing permits behind the Bronx, Brooklyn, and Queens.[23] However, the DEIS projection does not consider the economic feasibility of new construction, and the uncertainty concerning the economic feasibility of 485-x makes NYC DCP’s projections of future new construction questionable.

The projection about new units from conversions, while more modest, is also questionable. The same state legislation that created 485-x also created another new tax exemption, 467-m, for residential conversions that include below-market units. This incentive is less generous than 485-x and is structured to favor projects that commence construction by June 30, 2026. Benefits diminish for projects commenced after that date, and even more so for projects that begin construction after June 30, 2028. The benefit terminates on June 30, 2031. Since nonresidential buildings need to wait for the expiration of commercial leases before commencing construction, many potential conversions will be subject to MIH but eligible for diminishing tax offsets.[24]

Moreover, it is often difficult to convert commercial buildings into residential with modestly sized units associated with affordable housing. Recognizing this, the proposal includes a provision allowing the NYC Board of Standards and Appeals (BSA) to permit a cash contribution to an Affordable Housing Fund to substitute for the provision of onsite affordable units. According to the DEIS:

BSA must determine that the configuration of the building imposes constraints such as deep, narrow or otherwise irregular floorplates, limited opportunities to locate legally required windows, or pre-existing locations of vertical circulation or structural column systems that would create practical difficulties in reasonably configuring the required affordable floor area into a range of apartment sizes and bedroom mixes.[25]

However, since the cash contribution would not be offset by tax benefits, this is not a meaningful alternative. An existing provision allowing smaller MIH buildings to contribute to the same Affordable Housing Fund in lieu of providing affordable units has never been used.

BSA also has a separate “hardship” provision that allows a reduction or waiver of MIH affordability requirements that are found to be economically infeasible, but this has not proven to be a useful tool; like the Affordable Housing Fund provision, it has never been used. Applying to BSA is expensive and, in the absence of any guidance as to which cases might qualify for waivers, highly uncertain. Property owners prefer simply to leave their properties in their current condition and invest somewhere else. That implies that nonresidential buildings unsuited for a mix of market-rate and affordable housing will remain nonresidential under this proposal.

Sound Land Use Planning

Even if the Midtown South Mixed-Use Plan were economically feasible and able to produce all the projected housing, it would not necessarily represent good land-use planning. The DEIS identifies 62 “projected” sites where new housing under the plan will be developed and 7 “potential” sites where development is less likely to occur (Figure 7). The projected sites are occupied by vacant lots, parking lots, or small buildings and therefore make attractive development sites.

However, the plan has several flaws that make it less beneficial than it should be.

Failure to Consider Effects of Zoning Lot Mergers

A graphic provided in the DEIS indicates that most of the lots in the rezoning areas do not exceed 12 FAR, and in many cases are well below that amount (Figure 8). The graphic indicates that buildings over 12 FAR are most likely to be found among the bulky loft buildings in the Northwest Area (Garment Center), Fur District, and along Seventh Avenue.

None of the new construction sites are projected to exceed 18 FAR. The combination of zoning that permits buildings of 18 FAR, and sometimes additional floor area, in areas where the existing built context is often much smaller implies that NYC DCP believes that enormous volumes of zoned floor area will be left unused. Unfortunately, that is contradicted by the entire history of Manhattan since the 1961 comprehensive rezoning. FAR is an asset for profit-seeking property owners whose value can be realized only by using it. For buildings that are occupied and not considered development sites, the principal way this can be achieved is through a zoning lot merger. In a merger, multiple adjoining tax lots are combined, and buildings that are to remain transfer FAR to a building site whose “footprint” FAR—the ratio of the floor area within the building to the size of the tax lot on which it stands—far exceeds the “zoning lot” FAR.

Manhattan real estate developers use zoning lot mergers all the time. For example, the 40-story hotel on the northwest corner of Broadway and West 28th St., in the Southeast Area, merges its “footprint” lot with unused floor area on six additional tax lots (Figure 9). Its FAR is 12 on the zoning lot (the maximum allowed by the existing zoning district) and nearly 14 on its “footprint” lot.

Zoning lot mergers are not unlimited; generally, development rights must be contained within city blocks and merged lots must abut. However, the possibility of zoning lot mergers has several ramifications. First, new residential buildings can be much taller than the drawings in the DEIS (see Figures 3–6 above) show. Second, many more existing buildings are potential development sites, as real-estate developers seek buildings that can be vacated and demolished to provide “landing” locations for enormous quantities of otherwise “stranded” development rights.

Effects on Landmarks and Historic Districts

The likely role of zoning lot mergers has further implications. The proposed zoning is particularly destabilizing in the Northwest Area, where the National Register historic district provides financial incentives for preservation of the historic buildings but no prohibition against alterations and demolitions. The possibility exists not only of new buildings on the DEIS projected sites that are greatly out of scale with the historic built context that prompted the historic district designation, but also the demolition or incompatible alteration and enlargement of contributing buildings.

Additionally, the proposed zoning change in the Southeast Area raises the danger of damaging the two historic districts mapped within that area. Generally, historic districts should not be upzoned to a density well beyond the built context because such upzoning is inherently incompatible with the preservation objectives of the historic district. In this case, the proposed zoning conflicts with provisions of the state Multiple Dwelling Law that authorize residential buildings exceeding 12 FAR but which do not apply to buildings within LPC-designated historic districts.[26] The LPC could still find itself under pressure to approve inappropriately scaled new buildings adjacent to an historic district and using development rights from lots within the district.

Moreover, the enormous floor area increment in the Southeast Area undermines the ability of many designated landmarks to take advantage of their recently enhanced ability to raise preservation funding by transferring their unused development rights to a nearby site.[27] The Midtown South Mixed-Use Plan DEIS acknowledges that the proposal “would result in direct (demolition, shadows, and adjacent construction) and indirect (contextual) significant adverse impact to architectural resources.”[28] No specific mitigation of these adverse impacts is proposed, with more evaluation anticipated prior to the completion of a final EIS.

Effects on Existing Residences

In the Southwest and Southeast Areas, the potential for enormously tall buildings can be incompatible with the residents’ expectations of how much natural lighting they can experience at home. Many residential units obtain light only from windows on the 60-foot-wide side streets and on narrow rear yards. While these residents should have realistic expectations about new development—buildings with 10–12 FAR have been allowed since 1961, with no height limit—the proposed new zoning represents a significant change and greatly increases the potential for adverse effects on residents’ access to natural light.

Flawed Application of the 18 and 15 FAR Zoning Tools

The proposed zoning has the fewest effects in the Northeast, which is small, has few residents, and is surrounded by the tall towers of the Special Midtown District. That raises the issue of why this specific plan has been proposed, rather than one that would locate NYC’s densest apartment towers in the same areas where NYC’s dense office buildings are located. In the Special Midtown District (Figure 10), residences remain capped by zoning at 12 FAR. The decision to propose this plan, and not one focused on the Special Midtown District, is a consequence of the ideology of MIH set forth originally by the de Blasio administration—that MIH had to be mandatory and could never be a choice for real estate developers. That means that if the new 15 and 18 FAR residential districts were mapped in Midtown proper, affordability requirements would have to apply to any new building, even one with less than the 12 FAR of residential floor area permitted by existing zoning. Property owners would lose the right to build very lucrative market-rate condominiums up to 12 FAR and would be very unhappy.

However, this view of MIH is not immutable. The state law authorizing residential buildings to exceed 12 FAR, provided they comply with MIH, allows considerable flexibility to define MIH appropriately.[29] The MIH requirements could apply only where mandated by state law (buildings over 12 FAR). Good planning requires more ideological flexibility than is evidenced by the Midtown South Mixed-Use proposal.

For orientation, the two crosstown subway lines depicted are at 53rd and 42nd Sts. and the north/ south lines are at Lexington Ave., Avenue of the Americas, Broadway, 7th Ave. and 8th Ave. The proposed Northeast Area is shown as a cutout surrounded by the Special District.

Conclusion and Recommendations

The City Planning Commission and the City Council should adopt a modified version of the Midtown South Mixed-Use Plan with the following changes from the initial proposal. The proposed revised zoning is depicted in Figure 11. Modifications to the plan should include:

- The mapping of 18 FAR residential districts with MIH should be limited to the Broadway, Seventh Avenue, and Eighth Avenue corridors in the Northwest Area; the Northeast Area; the Seventh Avenue corridor in the Southwest Area; and the small blocks west of Broadway and north of West 28th Street in the Southeast Area. These areas are characterized by existing buildings that are at or exceeding 12 FAR.

- The existing M1-6D district in the historic Fur District should be left alone, except that the prohibition on converting buildings over 40,000 sq. ft. to residences should be removed.

- The remaining portions of the study areas should be rezoned to 12 FAR residential, consistent with existing maximum FARs for nonresidential buildings.

- City policy is to apply MIH in these areas. However, the special district should, for reasons of practical economic feasibility, exclude conversions of nonresidential buildings from MIH. That will greatly increase unit production from conversions and help reduce the city’s post-pandemic oversupply of Class B and C office space. More housing production from conversions will also compensate for the reduced rezoning FARs.

- NYC DCP should study the economic feasibility of MIH combined with the less generous 485-x tax exemption. Where the combination is shown to be infeasible, appropriate adjustments should be made in a future zoning amendment to the minimum required percentages of affordable housing.

- NYC DCP, BSA, and the Department of Housing Preservation and Development should work to make the BSA “hardship” waiver for economically infeasible MIH projects a meaningful option by providing clarity about the standards by which applications will be judged to qualify.

- NYC DCP should also study the applicability of the zoning districts allowing residences over 12 FAR to the Special Midtown District. Pragmatically, one option that should be studied is applying MIH only to buildings with a residential FAR over 12, where state law requires it.

NYC DCP’s Midtown South Mixed-Use Plan is a laudable effort to increase housing construction in Manhattan, the city’s wealthiest borough. However, planners have failed to take into account the full effects of their proposal. Aspects of the plan might adversely affect historic districts, hinder efforts by designated landmarks to raise funds for renovation and preservation, and deprive residents of reasonable access to natural light. Additionally, the city remains committed to problematic Mandatory Inclusionary Housing rules that act as a de facto entry tax on housing construction. The city’s practice of offsetting the cost of affordable housing mandates through the back door with tax exemptions is hindered by the state legislature’s recent efforts to have labor share in the benefits, offering less support to affordable housing than past programs. These issues should prompt the City Planning Commission and City Council to ensure appropriate modifications are made to the plan and policy changes implemented where needed.

Endnotes

Photo: Deven Dadbhawala / Moment via Getty Images

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).