Elizabeth Warren, U.S. senator from Massachusetts and candidate for president, recently released a Social Security plan that would exacerbate many of the program’s existing problems while also creating several new ones. The plan was announced in an article she posted on Medium, along with an analysis authored by Moody’s Analytics’ Marc Zandi. Normally, members of Congress have their Social Security proposals scored by the nonpartisan Social Security Administration Office of the Chief Actuary, but this proposal was introduced in a campaign context rather than a legislative one, hence the private analysis. While the proposal contains several substantive flaws, it serves the simple rhetorical message of promising higher Social Security benefits for all. The rationales given in Sen. Warren’s article for her plan exhibit several points of substantive confusion, which may partially explain why the proposal contains as many problems as it does.

It is impossible for an outside analyst to state with certitude why any particular public figure embraces a specific policy. Policy choices derive from several things, including subjective value judgments, gut instincts, one’s read of the substantive realities, political considerations, and many other factors. It is common for public figures to release plans accompanied by analytical findings that appear to support the proposed policies. However, the inclusion of such material rarely means that the policy was developed on the basis of neutral analysis of available information. At least as often, the analysis is provided as an after-the-fact rationale for policy choices driven by other subjective goals. This is particularly important to bear in mind when reviewing a Social Security plan such as Sen. Warren’s. An accurate understanding of the issues discussed in her Medium article would lead to policy proposals starkly different from the ones she has put forward.

The plan is a complex one and raises more issues than can be covered here. Below I will review a few of the major problems with it.

Problem #1: Misunderstanding Social Security benefits and replacement rates. In arguing for an across-the-board Social Security benefit increase, Sen. Warren writes:

“For someone who worked their entire adult life at an average wage and retired this year at the age of 66, Social Security will replace just 41% of what they used to make. That’s well short of the 70% many financial advisers recommend for a decent retirement—one that allows you to keep living in your home, go to a doctor when you’re sick, and get the prescription drugs you need.”

This presentation is inaccurate. The 41% percentage cited by Sen. Warren comes from a Social Security Administration (SSA) Actuary’s office memo, and is not actually a percentage of what a retiree “used to make” while working. Instead it is a percentage of the worker’s prior earnings “wage-indexed to the year before retirement”—that is, multiplied by subsequent average wage growth in the national economy. In other words, it’s not a comparison of that individual’s retirement benefits to his or her own previous earnings, but instead to the earnings of others who are working at the time the beneficiary retires. While this comparison may be of interest to some, it is not a measure of the degree to which retirees maintain their own pre-retirement standards of living.

This is a very significant error that essentially invalidates the argument advanced above. The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office (CBO) recently reported that Social Security will provide the average retiree born in the 1960s a benefit equal to 55% of the average inflation-adjusted value of their own career earnings. For workers in the lowest-income quintile, the average replacement rate is a much higher 80%.

When Sen. Warren’s mistaken interpretation of Social Security replacement rates is corrected, her foundational case for an across-the-board benefit increase disappears. Social Security replacement rates for low-income workers are already above the level Sen. Warren cites financial advisers as recommending, so they cannot be further increased without causing these Americans’ standards of living as workers to be much lower than they would later be as beneficiaries. In addition to being problematic for the workers themselves, this perverse outcome would create huge disincentives for labor-force participation and personal saving. Even middle-income Americans are already in a situation where Social Security is crowding out much of the saving they could or would otherwise do on their own for retirement. Unless we want to have Social Security displace nearly all long-term saving done by the lion’s share of Americans, the across-the-board benefit increase specified in Sen. Warren’s proposal runs counter to widely-expressed societal objectives for Social Security—namely, to provide a base of income protection underlying other retirement saving.

In fairness to Sen. Warren, SSA’s method of calculating replacement rates is counterintuitive and not widely understood. However, given the centrality of the data point to her piece’s case for a sweeping benefit expansion, it would presumably have been checked with a Social Security expert, most of whom are aware of the difference between how SSA defines this number and how the senator’s piece presents it. In addition, the CBO recently provided a comprehensive report to Congress detailing how SSA’s replacement rate calculations differ substantially from comparing a worker’s Social Security benefits to his or her own prior earnings.

Problem #2: Misunderstanding benefit increases under current law. Sen. Warren’s piece also contains the following statement in support of the case for an across-the-board benefit increase:

“…Congress hasn’t increased Social Security benefits in nearly 50 years.”

What this sentence omits is critical: a core reason no such legislation has been enacted in nearly 50 years is that federal law was changed back then to cause Social Security benefits to increase automatically without Congress having to act. Prior to the 1970s, Social Security operated very differently. Before then, Social Security benefits didn’t increase unless Congress enacted legislation to increase them. But in 1972, Congress passed a law (amended in 1977) that would cause Social Security benefit levels to increase over time, not only in absolute terms, but substantially faster than consumer price inflation. While people can differ over how large and generous the Social Security program should be, it is inaccurate to suggest that its benefits haven’t increased in nearly 50 years. The following graph shows how benefits for medium-wage workers have increased in real (inflation-adjusted $2019) dollars in recent decades.

Social Security Benefits Increase Automatically Under Current Law

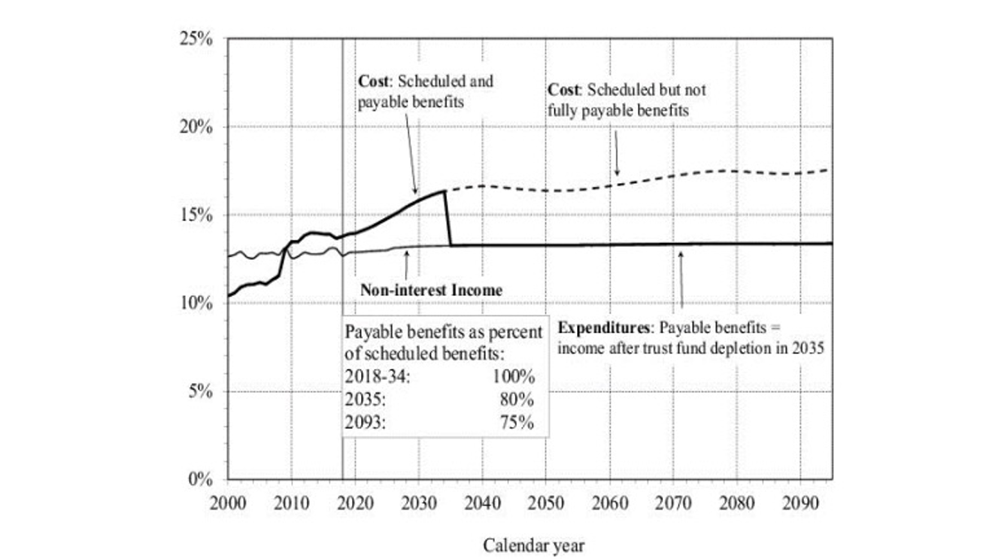

Instead of failing to increase Social Security benefits, we have the opposite situation: The current benefit formula causes benefits and costs to grow faster than our economic capacity and faster than workers’ earnings. It has been known since the 1970s that this rate of cost growth cannot be financed via a stable tax rate. Congress’s Social Security Consultant Panel cautioned back in 1976, “this Panel gravely doubts the fairness and wisdom of now promising benefits at such a level that we must commit our sons and daughters to a higher tax rate than we ourselves are willing to pay.” Sen. Warren’s proposal would cause the required tax increases to rise even faster, while her statement above creates a misimpression that is exactly opposite of what is happening. Instead of reflecting the reality that program benefits and costs are growing faster than is sustainable (as shown in the following figure reproduced directly from the Social Security trustees’ report), it fosters confusion to the effect that benefits haven’t been increasing at all.

Social Security Costs Grow Faster than Worker Wages

(All Numbers Expressed Below as a % of US Workers' Taxable Wages)

Problem #3: Worsening the treatment of younger generations. One of the biggest problems arising under current Social Security law is that it treats younger generations much worse than older ones. Because Social Security is not a savings program but rather an income transfer program, it is a zero-sum game at best: No one can gain net income through Social Security without someone else losing it. The largest such income transfers occur across generations. The trustees’ report shows that unless something is done to moderate the benefit growth rate for current participants, younger generations will lose income through Social Security equal to 3.4% of their career taxable earnings—net of all benefits they receive. The program cannot reasonably provide social insurance for young workers if it is making them more than 3% poorer over the course of their lives. By increasing benefits for today’s participants (including the wealthiest) well beyond what their own future taxes can finance, the Warren plan would substantially worsen the aggregate net income losses of younger generations.

Problem #4: Enabling state/local workers to double-dip benefits at Social Security’s expense. The Warren proposal would repeal provisions of Social Security law called the Windfall Elimination Provision (WEP) and the Government Pension Offset (GPO). In effect the plan would allow state and local employees to double-dip from the Social Security system, receiving much higher benefits than the program’s benefit formula intends. The reason that the WEP and GPO exist is that Social Security’s formula for computing benefits is very crude: It simply averages one’s highest 35 years of earnings, and applies a progressive benefit formula that pays higher returns to lower-wage workers than higher-wage workers. Because the system only “sees” earnings covered by Social Security, and because it computes benefits on the basis of lifetime average wages, at first glance it mistakes someone who works for 15 years under Social Security and 20 years in a state retirement system as having 20 years in which they earned nothing at all, in effect treating this person as having a much lower income than someone with the same annual earnings for 35 years under Social Security. The WEP/GPO adjusts benefits so that state and local workers aren’t mistakenly treated as much lower-income households than they actually are. The WEP/GPO doesn’t work perfectly and should be reformed. Texas Congressman Kevin Brady has a bill that would fix the formula to accurately reflect workers’ actual earnings, a perfectly good solution. Better still would be to reform the Social Security benefit formula altogether to obviate the need for the WEP/GPO. It would make no sense, however, to repeal the WEP/GPO without a replacement provision to prevent large overpayments of Social Security benefits.

Problem #5: Reducing saving. Social Security provides retirement income without generating additional saving to finance it, and accordingly has a net negative effect on national saving. The effects are particularly severe for low-income workers, whose burden of paying payroll taxes, combined with their income and liquidity constraints and Social Security’s benefit structure, causes many low-income households to suffer lower standards of living as workers than they anticipate as beneficiaries. Simply put, these households have neither the ability or incentive to engage in retirement saving after paying their Social Security taxes. Sharply increasing Social Security costs and benefits as in the Warren plan would considerably exacerbate these adverse trends, driving saving by low-income households even lower and discouraging saving by the middle class. Ironically, Sen. Warren’s piece cites low savings rates as a rationale for further expanding Social Security, when doing so would worsen this problem.

Problem #6: Mismeasuring inflation. The Warren plan would use an experimental index called the CPI-E to calculate beneficiaries’ annual cost-of-living adjustments. As I stated in a previous piece about another Social Security bill, “there is a general consensus among economists that CPI-E overstates price inflation relative to CPI-W (the measure Social Security currently uses), which in turn overstates inflation relative to C-CPI-U, a more accurate measure tracked by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Relative to accurate inflation indexing, the bill’s CPI-E would cause COLA overpayments of roughly 0.5 percentage points annually. . . . These overpayments would disproportionately benefit higher-income seniors who live longer, pushing costs and worker tax burdens higher.”

Problem #7: Weakening the economy through massive tax increases. The Warren proposal would increase national Social Security tax burdens by roughly 30% relative to current law. Even the Zandi memo issued in support of the proposal recognizes that these tax increases would reduce economic growth by having a “negative impact on the supply of labor.” Elsewhere the Zandi memo argues that the Warren proposal would increase economic growth over the long term primarily by reducing federal indebtedness, but this finding relies on an accounting convention that does not reflect actual law. This scoring convention assumes that in the absence of action, the federal government would continue to pay full Social Security benefits without collecting taxes sufficient to finance them, even though there is “no legal authority to make such payments.” Under a literal no-action scenario, current law would instead cause Social Security benefits to be cut dramatically when its old-age benefits trust fund runs dry in 2034. Alternatively, a different package of reforms to prevent trust fund depletion could be enacted before then. The key point is that the Warren plan would reduce economic growth relative to either a literal no-action scenario, or relative to an alternative solvency package that eschews the massive tax increases in her plan. Her plan only appears to improve economic growth starting in the 2030s, and only relative to a fictional budgetary scenario at variance with actual law.

The Warren Social Security plan would worsen Social Security’s intergenerational inequities, undermine saving, reduce labor-force participation, lower economic growth, employ an inaccurate measure of inflation, allow state and local employees to double-dip, and is premised upon fundamental misunderstandings of Social Security’s benefit structure. The plan would result not only in a far more expensive Social Security system, but also one with benefits less efficiently targeted for actual need.

Charles Blahous is the J. Fish and Lillian F. Smith Chair and Senior Research Strategist at the Mercatus Center, a visiting fellow with the Hoover Institution, and a contributor to E21. He recently served as a public trustee for Social Security and Medicare.

Interested in real economic insights? Want to stay ahead of the competition? Each weekday morning, e21 delivers a short email that includes e21 exclusive commentaries and the latest market news and updates from Washington. Sign up for the e21 Morning eBrief.

Photo by Mario Tama/Getty Images