Only Judges Can Close the Border

Introduction

One of the main campaign promises of the new Trump administration was to secure the border and carry out mass deportations, especially of criminals and recent illegal immigrants. But unfortunately, for many political leaders, increased enforcement is exclusively a matter of adding more border patrol agents or building physical barriers on the southern border. These measures ignore the Achilles’ heel of border enforcement: the immigration court system, which is badly underfunded and which allows illegal immigrants to stay indefinitely, despite clear laws mandating their removal. Unless this problem is resolved, illegal immigrants will continue to flood the border over the long run, because they will know that they can live and work in the U.S. for up to a decade before facing a judge. Every delayed immigration court hearing is an invitation for more illegal immigration.

Typically, an illegal immigrant can be deported only after an immigration judge issues a deportation order. If there are no judges to issue deportation orders, illegal immigrants remain in the country indefinitely as they wait for their cases to be heard. For decades, immigration courts have been underfunded, which—combined with record-setting illegal immigration during the Biden administration—has led to a backlog of 4 million cases. Even if illegal immigration falls to pre-pandemic levels now that Trump is in office, as long as the current number of immigration judges remains stable, it will take a decade to clear the backlog.

Illegal immigrants know about this backlog and that it presents an opportunity to enter the U.S., work illegally for years, and then, worst case, go back home on the taxpayers’ dime years later. Worse, criminal illegal immigrants—including gang members, drug traffickers, and repeat offenders—roam free in U.S. communities for years before facing deportation. Expanding immigration courts means getting dangerous criminals out of the country faster.

Thus, the longer it takes to hear a removal case in immigration court, the stronger the magnet to immigrate illegally; that’s why recent actions such as firing 20 immigration judges will only worsen this situation and will make securing the border harder.[1]

Without more immigration judges, Trump’s promise of mass deportations will fall flat. More than 13 million illegal immigrants reside in the country, but only 1.4 million of them already have a final order of deportation from a judge.[2] If the campaign of mass deportations were to begin today, it would quickly run out of deportable individuals. More ICE agents and detention space are needed to deport those who are deportable in a timely manner—but more immigration judges are also needed. Congress has recognized this challenge and rightfully included 1.25 billion dollars in additional funding to hire and support immigration judges over the next five years. This is an excellent step.

Some might prefer a more radical solution: scrapping the immigration court process altogether so that deportation no longer requires an order from an immigration judge. Depending on the details, this argument may have merit in the abstract. But it is irrelevant: the right to asylum and the Immigration and Nationality Act are set in statute by Congress, and altering the process would require 60 senators and a majority of the House, which immigration hawks are unlikely to garner. More important, such a radical change is unnecessary; to carry out mass deportations and secure the border now, the U.S. does not need any changes in the law but only more funding for enforcement, which means funding immigration courts.

Immigration Court Backlog

The Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) reports that there are approximately 4 million pending cases in front of immigration judges (Figure 1).[3] This does not include the 1.5 million pending affirmative asylum cases filed with United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS),[4] which typically involve those who enter on a visa and overstay because of fear of returning to their home country. The consequence of this growing backlog is that it takes longer to get a hearing in front of a judge. Instead, as long as illegal immigrants claim some credible fear of returning home, they are released into the U.S., only to have their cases heard a decade into the future.

If there is no change in the current number of immigration judges (701)[5] and if illegal immigrant flows at the southern border return to normal, pre-Biden administration levels, the backlog of pending cases will start to fall—but slowly. As shown in Figure 2, By the last year of Trump’s final term, there will still be more than 3 million people with cases pending in immigration courts, none of whom can be deported until their cases are decided. Without more immigration judges, it will be impossible to drastically reduce the illegal immigrant population.

Of course, some of those with pending cases will ultimately receive favorable decisions from the immigration court. Over the last 27 years, some 15% of immigration court cases that were not closed or dismissed (two outcomes that became increasingly common during the Biden administration)[6] have resulted in some form of relief granted to the immigrant—e.g., asylum, withholding of removal, or another status that prevents removal (Figure 3). But that means that 85% of these decisions result in final orders of removal or voluntary departure. If this ratio holds for the current backlogged cases, 3.4 million out of the 4 million immigrants with pending cases will be deportable, and only 600,000 will be granted a right to remain.

Affirmative Asylum Backlog

The affirmative asylum backlog is also worsening, at more than 1.4 million cases as of December 2024 (Figure 4).[7] But these cases are typically not as exigent as those of unvetted border crossers because they generally involve individuals who obtained a visa to enter the U.S. in the first place and thus are far less likely to be violent criminals. Still, the growing backlog encourages tourists and other visa holders to file for asylum to remain in the country for years, as their cases are adjudicated.

The main driver of the growing backlog is the record number of asylum requests made during the Biden administration by those paroled at the border or as part of the Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Venezuela (CHNV) parole process. This has placed significant strain on USCIS, especially because the agency is almost entirely self-funded through user fees, rather than through taxpayer dollars appropriated by Congress; but asylum applicants don’t pay a fee. Last year, to help fund the asylum backlog, the Biden administration implemented a new fee rule that increased fees for high-skilled immigrants by up to $600.[8] But asylum seekers continue to pay no fee to apply, and there will likely be hundreds of thousands more applications in the coming years from Biden-era migrants whose parole is set to expire and from those affected by Trump’s moves to revoke Temporary Protected Status. Without funding, USCIS simply will not be able to process these applications, and the applicants will remain in the country regardless of the accuracy of their asylum claims.

Expanding Immigration Courts

How many more immigration judges do we need? It depends on what the goal is. Clearing the immigration court backlog by the end of the Trump administration will require hiring an extra 250 judges per year. Assuming no change in how many cases each judge decides per year (currently 957), this would shrink the immigration court backlog from 4 million to about 100,000 by fiscal year 2029—which begins in October 2028, the final months of the Trump presidency. Alternatively, hiring only 100 immigration judges annually over the next four years would reduce the backlog to 1.8 million in fiscal year 2029 and would completely clear it by fiscal year 2032.

The “One Big Beautiful Bill” that Congress is debating contains enough funding to add approximately 250 judges over the next five years but leaves these positions unfunded afterwards. The bill would thus end the immigration court backlog by 2032 as long as current low levels of illegal immigration continue, but it would not be provide enough judges to issue deportation orders for all pending cases by the end of the Trump administration.

If the Trump administration is serious about enforcing immigration law, it should seek to expand immigration courts aggressively. Immigration judges are executive-branch employees; after Congress funds positions, new judges can be hired without confirmation hearings, in a process much quicker than that used for Article III judges.

Cost Estimates

In its fiscal year 2025 budget request, the Department of Justice requested 25 new immigration judge positions, as well as 37 new legal assistants, 38 attorneys, and 50 professional and other administrators to accompany these judges.[9] It estimated that these positions would cost $32,785,000, or approximately $1.31 million per immigration judge added. Therefore, we can assume that it would cost $131 million to add 100 immigration judges in FY2025, and $328 million to add 250 judges.

To expand immigration courts, Congress would need to include this funding in a reconciliation bill, which involves producing a 10-year cost estimate for this policy. To do this, I assume that the cost of employing these federal judges and staffers grows at the same rate as overall projected discretionary spending according to the Congressional Budget Office, which is slightly higher than inflation.[10] I then assume that, after four years, immigration court hiring stops—no judges are added, while the attrition rate due to retirement or termination matches that of the past decade (approximately 5.6% annually) (Figure 5).[11] I do not assume that all the additional judges will be immediately separated from employment after the backlog is cleared, because few people would apply for a position that could last only a maximum of four years. Allowing for natural attrition does increase the cost of the policy, but it is more realistic.

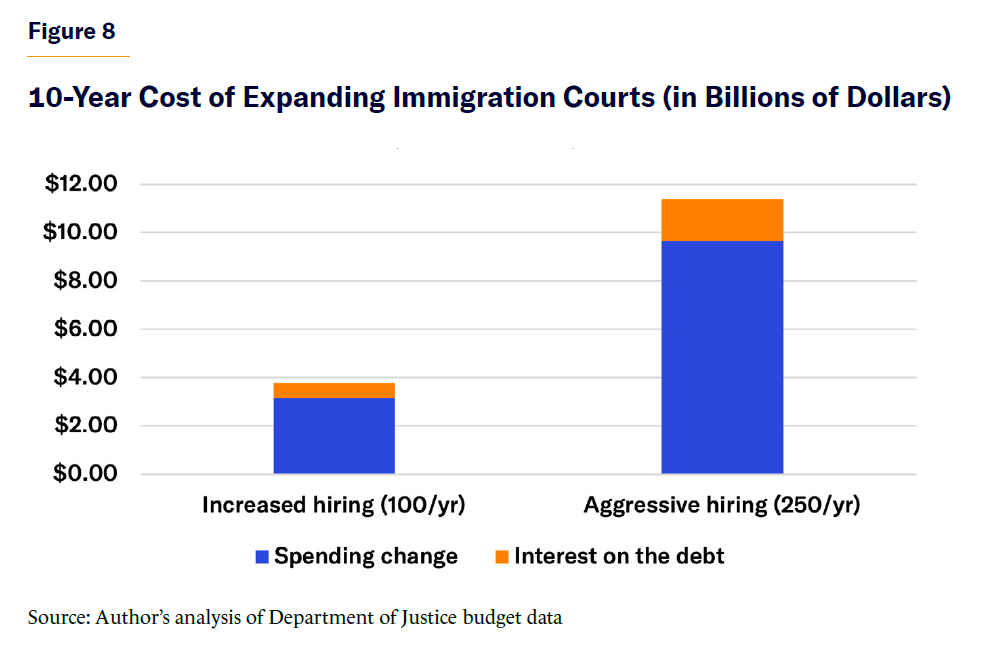

The total 10-year cost of the aggressive hiring scenario (250 new judges per year) would be approximately $11.38 billion, with $9.65 billion in direct spending and $1.73 billion from added cost of servicing the debt. This spending, about $1 billion annually, or $3 per American, would be a large increase relative to these courts’ current budget, but it is a small price to pay to fully clear the asylum backlog. In this scenario, the budget of EOIR would more than double from its baseline at the peak of the expansion, and then gradually converge back to the baseline. Figures 6 and 7 show the change in the budget of EOIR under the various scenarios.

Under the moderate hiring scenario (100 new judges per year), the 10-year cost of expanding immigration courts would be $3.76 billion, including $3.13 billion in direct spending and $630 million from added interest on the debt (Figure 8).

Solving the Affirmative Asylum Backlog

Two main solutions should be implemented as soon as possible to deal with the affirmative asylum backlog and end the magnet for new illegal immigrants:

- Implement a last-in-first-out rule both in immigration courts and USCIS asylum filings.

- Charge a $1,000 asylum filing fee to applicants for asylum with USCIS as proposed by Congress in the “One Big Beautiful Bill.”

Last-In-First-Out

The Trump administration should order immigration courts and USCIS to process asylum cases in reverse order of filing date—that is, prioritize those filed this year over those filed in previous years. This ensures that new asylum cases are decided quickly—which, because most of these decisions will be denials, will discourage those currently considering coming to the U.S. from filing false asylum claims. This strategy was adopted during Trump’s first term, and it had a deterrent effect as intended. However, because it was not combined with other solutions to ramp up processing, old cases were left collecting dust without decisions, creating a de-facto amnesty and leaving millions in legal limbo.

Implementing an Asylum Fee

Rather than forcing others to pay for the mess, we should raise the funding needed to close the asylum backlog by charging asylum seekers a reasonable processing fee. Applying for asylum is already expensive because applicants often hire lawyers. An additional $1,000 fee would not be difficult for true claimants and would discourage frivolous filings while raising over $400 million annually at the current filing rate of more than 400,000 cases. This would allow USCIS to hire hundreds more asylum officers to review their cases and remedy the backlog. Charging this fee to asylum applicants would also make the system as a whole more fair, by not imposing even higher costs on high-skilled immigrants, who already pay thousands of dollars in fees throughout the application process.

Conclusion

Laws lose their meaning when they are not enforced. In the immigration system, this non-enforcement is largely driven by the significant underfunding of the courts, which have become a major bottleneck after years of rising illegal entries. The result is that millions of migrants have ended up in years-long legal limbo, while the U.S. is unable to deport those who legally should not be present in the country.

Congress is right to fund immigration courts in the “One Big Beautiful Bill” as proposed but 1.25 billion over five years will fall short of accomplishing President Trump’s mass deportation goal even in the lowest illegal immigration case scenario. However, for just about $1 billion a year, the U.S. government would finally be able to enforce immigration laws properly, reduce illegal border crossings, and avoid billions in taxpayer-funded welfare and benefits for illegal immigrants. Even in the best scenario for the president, in which these positions are funded just for the next four years, Congress should allocate some $4 to $5 billion to fully get rid of the immigration court backlog during Trump’s Presidency.

The only way to permanently solve the illegal immigration crisis under current law is greater enforcement. That requires allowing immigration courts to do their job in determining who should be deported and who should remain. Republicans have campaigned on stopping illegal immigration; expanding immigration courts would do just that. Hiring more immigration judges is the most legally and cost-effective way to address the consequences of mass illegal immigration and enforce the law once and for all.

Endnotes

Photo: stocknshares / iStock / Getty Images Plus

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).