Correcting the Core University General Education Requirements Need State Oversight

Introduction

Universities across the U.S. are struggling to rebuild public trust, as many Americans are concerned about politicization and the return on investment of a college degree. At their best, universities impart knowledge and skills that students can apply both as informed citizens and in their careers. They are places of innovation, where research-driven students gain firsthand access to innovative technologies that shape our economy and drive our country’s success.

But universities have abused their role as custodians of students and stewards of taxpayer dollars by blurring the line between education and activism, especially in introductory course work or in required courses necessary to fulfill general education requirements. One way to restore trust is for universities, as well as the public officials responsible for oversight at the state level, to revisit those general education requirements that students must complete at public universities.

This report looks at ways to reduce politicization in general education courses and streamline the options offered to students. Key points:

- Revisions to general education requirements in Florida, which this brief uses as a case study, reduced activist-oriented courses and streamlined options for students.

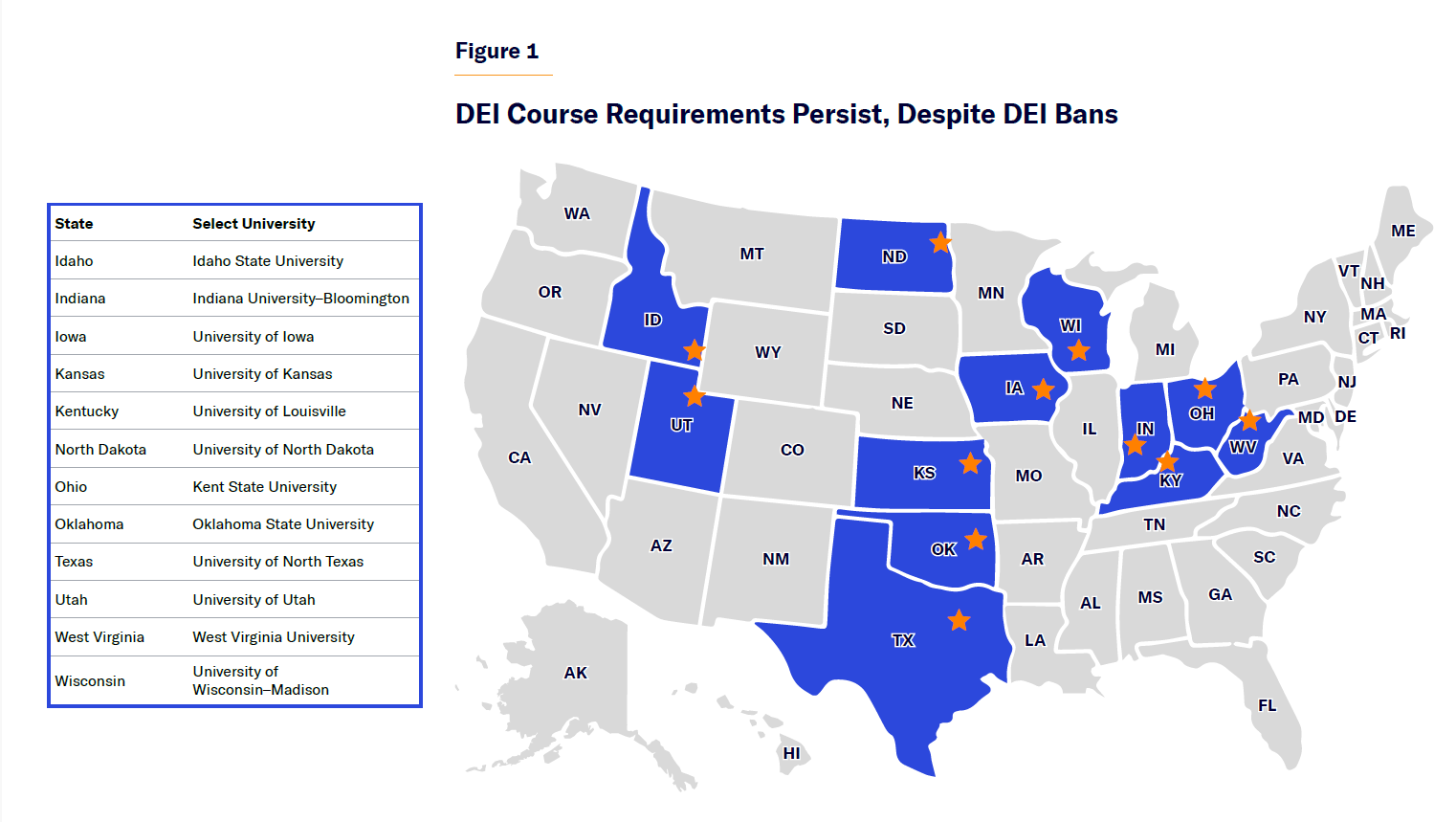

- Diversity requirements, whether embedded in general education programs or stand-alone graduation mandates, remain present in 12 states with diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) bans on the books.

- As public institutions funded by taxpayers, universities must ensure that general education courses are academically rigorous and broadly applicable, as opposed to advancing one political worldview.

The report concludes that state lawmakers must take a more active role in revisiting general education requirements in order to restore trust in higher education.

Background: General Education Requirements

Universities require general education to ensure that all graduates possess a standardized base of knowledge common to all students. This base is intended to cultivate within students a broad understanding of the fields of human inquiry and how various disciplines create, interpret, and apply knowledge. When executed well, students develop an appreciation for distinct methods, questions, and evidence that shape various fields of study by engaging in subjects outside their majors. They also have the opportunity to see where the various fields of human inquiry overlap. This kind of exposure builds intellectual flexibility so that students can engage responsibly with information in a pluralistic society.

The advent of general education followed the rise of modern universities. Prior to general education requirements, American colleges followed a strict and narrower curriculum rooted in classical studies. Universities focused on subjects such as Greek, math, and theology.[1] Students took the same courses with little flexibility for specialization or electives. But with the rise of professionally oriented programs driven by industrialization and the increased access to higher education through the Morrill Land Grant Act of 1862, universities began to prioritize practical and vocational skills.[2]

Yet the move to electives and specialization created its own set of challenges. University leaders noticed that students were increasingly disengaged from broader forms of knowledge and intellectual engagement. As former University of Chicago president Robert Maynard Hutchins put it: “The aim of education is to connect man with man, to connect the present with the past, and to advance the thinking of mankind. If this is the aim of education, it cannot be left to the sporadic, spontaneous interests of children or even of undergraduates.”[3] In the early 1900s, universities began to modify their curricula to include a shared set of general education courses. General education gained widespread traction after World War II, with some estimating that half of universities had adopted general education requirements by 1955.[4] Amid Cold War tensions and the West’s need for a cohesive front against Communism, education leaders recognized that citizenship in a democratic society requires deliberate teaching and could not be taken for granted.[5]

Despite its important role, general education today often falls short of its intended purpose. Many programs have become bloated and unfocused, where foundational introductions to a discipline, such as “Introduction to Literature,” are mixed with highly niche or specialized topics such as “The Rise of Modern Fantasy: Dragons, Elves, and the Building of Imaginary Worlds.”[6] While specialized topics may hold value in their own right, they are ill-suited as entry points into a field and can confuse, rather than clarify, core principles that students should learn.

General education has also drifted toward activism, emphasizing ideological commitments over academic inquiry.[7] This results in curricula that are disconnected from broadly shared American civic and intellectual values. As a result, students may graduate from college without gaining the broad knowledge or critical thinking skills that justify the existence of general education in the first place. Students instead leave with a fragmented understanding of the world and limited transferable skills rather than becoming better prepared to participate in a democratic society.

One way in which general education requirements often bend toward activism is by creating diversity course requirements. Diversity course requirements have students take classes that are fixated on identities or approach social issues through a progressive lens, emphasizing topics like privilege, oppression, and systemic discrimination. These are categories defined by the universities themselves, often labeled in catalogs as “diversity requirement,” “cultural diversity,” “equity and inclusion,” or similar terms. Not all such requirements are technically included in the general education requirements; they may be stand-alone requirements instead. However, the effect is the same: students must take these courses in order to graduate. In fact, a 2024 report found two-thirds of the colleges investigated required students to take a DEI course to graduate.[8]

Because of these issues with general education, some have concluded that the whole project is flawed.[9] Critics argue that K–12 is already a form of general education and that many university general education courses are redundant or irrelevant to students’ career goals, or that the requirements can feel like a bureaucratic obstacle rather than an intellectual opportunity.[10] These frustrations reflect real shortcomings of the way general education is currently designed and delivered. But they mischaracterize today’s misuses of general education with its purpose. Especially in an age of rapid technological advancement, students need transferable skills that can stand the test of time—the kind of skills that general education requirements can instill.

There are also administrative reasons that general education requirements are useful. Importantly, general education requirements can assist with the smooth transfer of credits between universities, which is particularly true when general education requirements are set at the state level for all public universities. These requirements ensure not only that all students at a particular school receive a comparable exposure to key disciplines but also that all students attending public universities in the state receive that same curriculum.

Regardless of one’s views, general education requirements remain a fixture of American higher education, and universities are not dropping them anytime soon, which makes it all the more important for higher-education reformers to participate in the general education requirement-setting process.

The National Landscape

Across the country, several states have banned diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) practices at universities in order to safeguard universities from political bias and racial discrimination. But banning DEI is not enough to address the politicization of universities (Figure 1). For instance, Ohio lawmakers banned hiring based on DEI requirements in 2025. But that law has not stopped universities like Kent State from mandating diversity courses for students.[11] Similarly, the University of Utah requires students on the baccalaureate track to take a diversity course, despite the state’s ban on DEI in 2024.[12] And Arkansas’s recent DEI ban does not prevent activist courses like “Social Problems,” where students analyze issues from a sociological lens with “emphasis placed on social justice,” from general education consideration.[13]

State legislatures must take a more active role to rein in the mission drift at public universities. They can do so by reforming general education requirements.

States generally exercise some oversight over general education programs at public universities, particularly through statewide core curriculum frameworks or transfer guidelines. This oversight is usually limited to establishing broad requirements, such as subject areas, total credit hours, and transferability rules to ensure that students can move between state schools without losing credit. But most states take a hands-off approach on academic matters, leaving significant discretion to faculty. While state-appointed governing boards, like a board of regents, provide oversight, they typically defer to faculty committees on matters of curriculum and instruction. State policies may set general expectations, such as the total number of credits or required subject areas, but they typically do not decide the credit hours or content for institution-specific general education courses. Faculty committees or academic departments, instead, propose and approve these courses internally.

The modern university governance model heavily weighs faculty input on academic matters because, as subject-matter experts, the faculty are assumed to be suited to guide the development of course content. External actors like state governments, meanwhile, are expected to avoid micromanagement, as they are less familiar with current research and pedagogical best practices.[14]

The assumptions made under this model work only if faculty uphold academic standards and avoid using the classroom to promote ideological agendas; and if university boards hold faculty accountable when they cross lines. But faculty and academic departments have eroded trust by advancing activist agendas. For instance, the University of Alaska considers “decolonizing teaching practices” as a “pedagogical or assessment innovation,” which is one criterion that proposed courses should meet before the university’s General Education Council evaluates them for approval.[15] In such instances, states should be able to intervene and ensure that public universities remain aligned with their academic missions to assure public accountability.

State governments need to remember that there are other stakeholders in public higher education: taxpayers and students. The current, outsize influence of faculty means that courses may be kept—not because the courses benefit students but to protect a department from insolvency.[16] The fear of a department being eliminated is a poor reason to keep a requirement or course. Universities must prove that a course is intellectually valuable and how it benefits students.

A straightforward solution would appear to be cutting all courses that promote DEI or social justice. But lawmakers will quickly run into legal roadblocks. The courts have repeatedly viewed academic freedom as protected under the First Amendment to preserve instruction and debate from external pressure.[17] A more strategic approach is for lawmakers to balance the needs of all stakeholders. Ending diversity course requirements, placing stricter standards on general education course qualifications, and periodically reviewing courses all address politicization and the quality of courses while preserving academic freedom.

Case Study: Florida

In 2023, Florida lawmakers passed SB 266, which prohibits the state’s core general education courses from promoting historical distortions and political agendas.[18] Florida has a 15-credit statewide general education core that is required for students who attend any of Florida’s public universities. Each public university, such as Florida State or the University of Florida, can have its own general education framework beyond the statewide core. SB 266 also implemented a review process for all general education requirements, including noncore courses, at Florida public universities.

SB 266 gave greater oversight power to Florida’s Board of Governors (which oversees 12 public universities) and the State Board of Education (which oversees 28 state colleges). These boards now have the final say on the courses that can be included in the general education curriculum. Individual universities still review all their general education courses separately. Anticipating political pressure and potential funding loss, universities took a more cautious approach to submitting their courses for approval after the law’s passage.[19] After the law was passed, the Florida Department of Education reported a nearly 60% decrease in the number of general education classes across its 28 state colleges.[20]

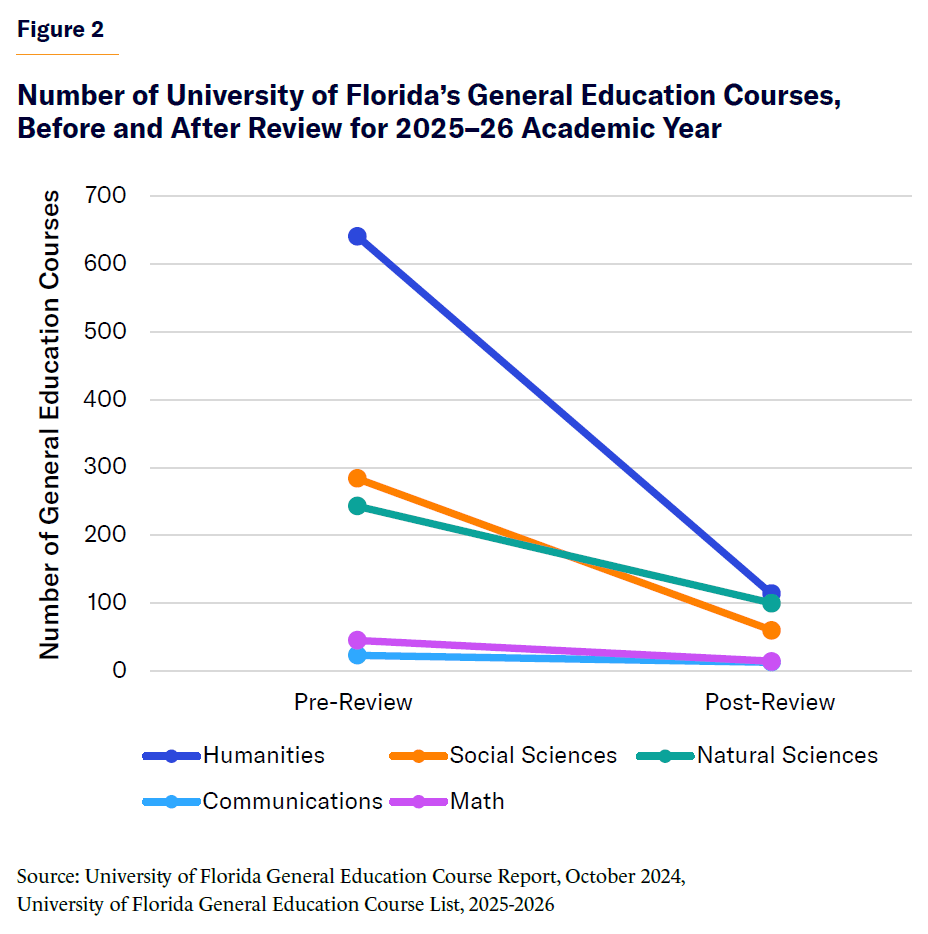

We took a closer look into the University of Florida to illustrate the law’s effect. The University of Florida originally proposed more than 1,200 courses for general education status.[21] Following the review process for the 2025–26 academic year, nearly 300 courses at the University of Florida were approved—a 75% reduction.[22]

The University of Florida categorizes courses into five fields: communications, humanities, math, natural sciences, and social sciences. Figure 2 shows that all fields experienced declines after the law took effect. Humanities and social sciences saw the steepest declines, with a reduction of 527 courses and 224 courses, respectively.

Departments that are particular hotbeds for activism and controversy were most likely to have their classes removed from the general education list. For example, none of the women’s studies courses qualified for general education status in the 2025–26 academic year. Other courses that were removed because of the state’s revised standards included “Be a Social Justice Activist: #Activism, Intersectionality, and Social Movement Organizing,”“Latin American and US Latinx Theatre,” and “Diversity and Inclusion in Sports Organizations.”

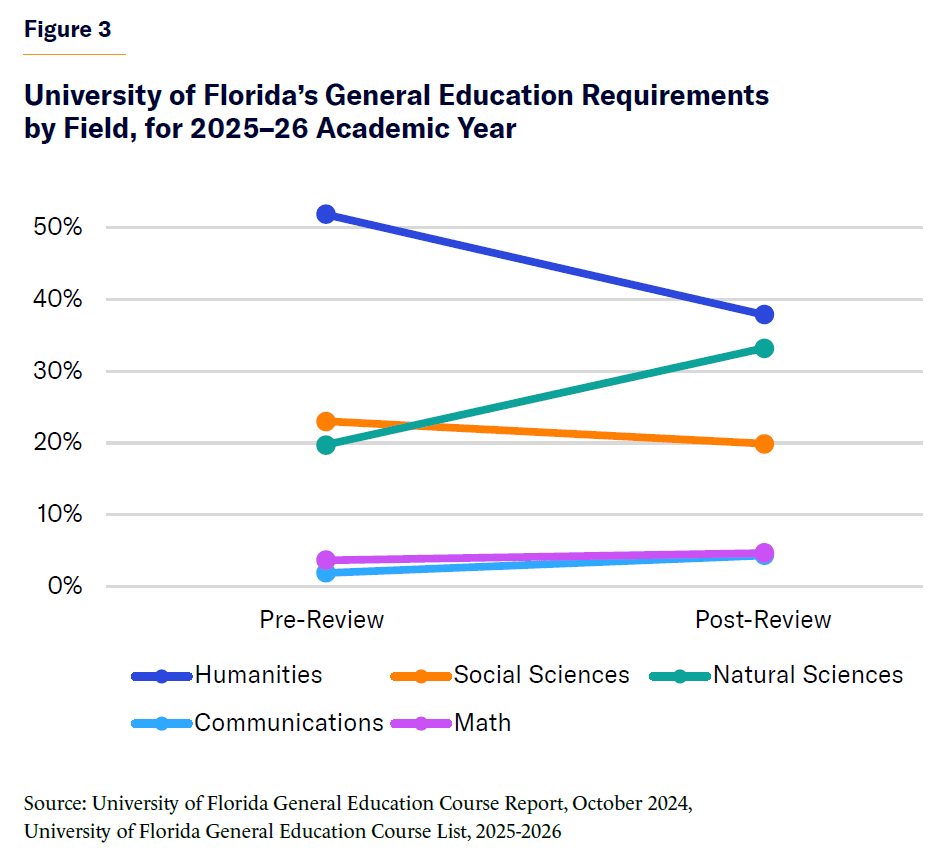

Figure 3 shows the distribution of fields represented in general education. Prior to the review, humanities represented over half of general education courses, followed by social sciences (23%), natural sciences (20%), math (4%), and communications (2%). For the 2025–26 academic year, humanities still represent the largest proportion of general education classes, but now at 38%. Natural sciences gained in proportion, making up 33% of the courses, while social sciences fell slightly to 20%; math (5%) and communications (4%) saw slight increases.

A common criticism levied against the Florida legislature’s revision of the general education courses is that it is merely a way to “implicitly weed out classes that do not subscribe to ‘Western’ perspectives or topics.”[23] But that narrative is oversimplified. The University of Florida maintains general education courses on various world religions, like “Religions of India” and “Introduction to Buddhism.” Florida A&M University offers “Afro-American Music.” Florida International University has “Politics of Latin America.” And just because a course covers aspects of the West does not guarantee approval. The University of Florida, for instance, did not recognize “Modern Britain” and “New Testament Greek” for general education status.

Florida’s approach could be improved by other states, however. Current language leaves Florida’s law vulnerable to legal challenges.[24] And its broad approach, while cutting down on activist courses, has unnecessarily affected legitimate courses like Florida International University’s “Introduction to Machine Learning.”[25]

Many states could still benefit from reviewing their general education offerings.[26] For instance, the University of Arizona currently offers more than 500 general education courses. At least one-third focus on race, identity, and activism, by my assessment. The College of Charleston (South Carolina) also offers more than 500 general education courses, with at least 11% focusing on race, identity, and activism. Out of the 11% of general education courses that focus on race, identity, or activism, 95% come from the humanities or social sciences. See the Appendix of this paper for a sampling of general education courses offered that could be sensibly cut.

As the public grows increasingly skeptical of higher education’s ability to reform itself, we must remember that universities still play a vital role in cultivating talent, making discoveries, and supporting our economy. Not all departments are driven by activism, and only some departments have undermined the reputation of other serious and rigorous programs. Rebuilding trust requires states to hold institutions accountable—rewarding genuine academic rigor and refusing to propagate ideological agendas.

Recommendations

1. End Diversity Graduation Requirements

Some universities have begun to suspend DEI requirements because of pressure from the Trump administration.[27] But many continue to keep them. State governments should ensure that universities do not compel students into specific ideologies and beliefs by way of diversity requirements. If individual majors must offer diversity-related course work to adhere to accreditor or licensure policies, university leadership should offer limited waivers to work around accreditor mandates.

2. Eliminate Activism in General Education Courses

States manage public university governance differently. I recommend adapting the following language from Florida’s law to give quality options to students. My revisions, in Table 1, aim to add clarity and protect students from compelled speech and belief.

Table 1

Adapted Language from Florida General Education Law

| Definition: “Promote or endorse”: to present as objectively true or morally normative without offering substantial room for analysis, debate, or dissent | |

| Florida | Revised Language |

| General education core courses may not distort significant historical events or include a curriculum that teaches identity politics, violates § 1000.05, or is based on theories that systemic racism, sexism, oppression, and privilege are inherent in the institutions of the United States and were created to maintain social, political, and economic inequities. | General education courses may not: a) Include curriculum that promotes or endorses theories asserting that individuals are inherently oppressive, privileged, or morally to blame based on their ethnicity, national origin, race, sex, or other protected characteristics; b) Violate {insert applicable state antidiscrimination law/s}; c) Promote or endorse the belief that the United States or its institutions were established to maintain social, political, and economic inequities on the basis of protected characteristics and that such inequalities are inherent or permanent features of these institutions; d) Require students to adopt, affirm, or internalize specific ideological, political, or social beliefs as a condition of academic participation or evaluation. Nothing in this section prohibits the objective academic discussion or examination of such theories, provided that such instruction does not compel student agreement or present such theories as the only moral or intellectually valid perspective. |

Annual Review of General Education Requirements

The appropriate state agency should annually review and approve general education courses at its public universities to check whether they are aligned with the above requirements. A list of approved courses should be available on the state’s department of education website.

Place Eligibility Caps for Academic Departments

State governments can streamline general education courses by capping each academic department to 10% of its own undergraduate course inventory or five courses, whichever is greater. A cap would reduce the administrative burdens on curriculum review committees. Without such limits, departments may flood the review process with excessive course proposals, expecting only a small fraction to be approved, which would strain the review system and dilute the effectiveness of the review process. A cap based on percentage rather than the raw number avoids penalizing larger departments. A percentage cap, rather than a raw number, also avoids encouraging smaller departments to spin off into more departments, just to have more courses represented under general education.

Conclusion

Restoring general education at public universities is essential to realigning them with their core academic and civic missions. States have a legitimate interest in maintaining rigor in general education. It is not only about guiding students toward meaningful learning outcomes but also about ensuring that public universities remain accountable stewards of taxpayer funds. A well-designed, focused general education curriculum can equip students with the intellectual tools to navigate life after college and to participate thoughtfully as citizens.

Appendix

Select General Education Courses Nationwide

| State | University | Sample Courses |

| AL | University of Alabama | Anti-Oppression Social Justice Social Justice in the Hispanic World The Latinx Experience |

| AK | University of Alaska | Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Through Community Service Learning Introduction to Gender and Sexuality Studies Decolonizing Methodologies |

| AZ | University of Arizona | Race, Racism, and the American Dream The Social Construction of Race: Whiteness Wokeness: Power, Identity, and the Psyche in Contemporary America |

| AR | University of Arkansas | Introduction to Gender Studies Social Problems |

| CA | California State University–Fullerton | Black Lives Matter Creative and Critical Ideas Art and Social Justice Queer Literature and Theory |

| CO | University of Colorado–Denver | Foundations in Social Justice Through the Lens: Photography and Diversity Introduction to Chicanx and Latinx Studies |

| CT | University of Connecticut | Power, Privilege, and Public Education Feminisms and Arts Devising Theatre for Social Justice I |

| DE | University of Delaware | Re(de)constructing AfroLatinx Intersections Racial Identity, Bias, and the Self Religion and Social Justice |

| GA | University of Georgia | Race and Ethnicity in America Introduction to LGBTQ Studies Survey of Diverse Literature for Young Audiences–Service Learning |

| HI | University of Hawaii–Manoa | Gender and Race in U.S. Society Latinx Experience in Hawaii Oceanic Ethnic Studies: Theories and Methods |

| ID | Idaho State University | Critical Analysis of Social Diversity Introduction to Gender and Sexuality Studies |

| IL | University of Illinois–Urbana-Champaign | Feminist and Queer Activisms Race, Social Justice, and Cities Education and Social Justice |

| IN | Indiana University–Bloomington | Popular Music Critical Theory Understanding Diversity in a Pluralistic Society Seeing Black Resistance Through Relational Lens |

| IA | University of Northern Iowa | Exploring Social Justice Issues Through Math American Racial and Ethnic Minoritized Populations Intro to LGBTQ+ |

| KS | University of Kansas | Language, Gender, and Sexuality Perspectives on Science, Engineering, and Mathematics Perspectives in Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies |

| KY | University of Louisville | Gender, Race, Sexuality in Children’s Lit Art and Social Justice Social Justice |

| LA | Louisiana State University | Language Diversity, Society, and Power Gender, Race, and Nation Introduction to Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies |

| ME | University of Maine | Introduction to Feminist and Critical Data Analysis Ethics and Social Justice in Outside Leadership Intersectionality and Social Movements |

| MD | University of Maryland | The New Jim Crow: African-Americans, Mass Incarceration, and the Prison Industrial Complex Social (In)Justice and African-American Health and Well-Being Introduction to WGSS: Gender, Power, and Society |

| MA | University of Massachusetts–Amherst | Writing, Identity, and Power Self-Awareness, Social Justice, and Service Race, Gender, Sexuality, and Equity |

| MI | Western Michigan University | Gender and Plastic Bodies Women of Color in the United States The Black Community |

| MN | University of Minnesota–Twin Cities | Queer Kinship: Undoing the American Family Women, Rage, and Politics Race, Power, and Justice in Business |

| MS | University of Mississippi | Introduction to Queer Studies Advanced Queer Studies Gender Theory |

| MO | University of Missouri–Columbia | Studies in Black Feminist Thought Social Justice for Educational Leaders Decolonizing Methodologies |

| MT | University of Montana | Feminist and Queer Theories and Methods Race, Gender, and Class Social and Political Perspectives on Gender and Sexuality |

| NE | University of Nebraska–Omaha | Diversity in Aviation Principles of Sustainability: Impact of Individuals and Organizations on Ecology, Equity, and Economics Introduction to LGBTQ Studies |

| NV | University of Nevada–Las Vegas | Critical Race Feminism Leadership and Social Identity Sociology of Education and Race |

| NH | University of New Hampshire | Race and Diversity in the U.S. Social Stratification and Inequality |

| NJ | Rutgers University | Queer Crime Social Justice in Film |

| NM | University of New Mexico | Introduction to Environmental and Social Justice Introduction to Comparative and Global Ethnic Studies The Dynamics of Prejudice |

| NY | State University of New York–Binghamton | Archaeology and Social Justice AI, Deepfakes, Race, and Gender Queer World Literature |

| NC | Appalachian State University | Social Diversity and Inequalities Gender, Race, and Class Foundations for Social Justice Practice |

| ND | University of North Dakota | Bridging the Divide: Dialoguing Across Identity Differences Multicultural Education Curriculum and Pedagogy in Indigenous Education |

| OH | Ohio State University | Introduction to Queer Studies Issues in Social Justice: Race, Gender, and Sexuality Queer Comrades: Sexual Citizenship and LGBTQ Lives in Eastern Europe |

| OK | Oklahoma State University | Minorities in Science and Technology: Contributions Past, Present, and Future Social-Justice Politics American Stories: Diverse Peoples in YA Literature |

| OR | Oregon State University | Antiracism and Diversity, Equity, Inclusion in Practice Higher Education Goes Hollywood: Racial Narratives and Student Experiences Arts and Social Justice |

| PA | PennWest California | DEI at Work Advanced Studies in Literature, Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Social Advocacy |

| RI | University of Rhode Island | Queer Studies: Identities, Perspectives, and Social Justice Education and Social Justice Leadership for Activism and Social Change |

| SC | College of Charleston | History of Queer America, 1600–2000 Geology—Race, Equity, and Inclusion Elementary Statistics—Race, Equity, and Inclusion |

| SD | South Dakota State University | Sustainable Society Introduction to Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies |

| TN | University of Tennessee–Knoxville | Social Justice and Community Service Social Problems and Social Justice |

| UT | University of Utah | Feminist Economics Exploring Identity Through Storytelling for Engineers Identity and Justice in the Built Environment |

| VT | University of Vermont | Interrogating White Identity Critical Race Feminist Theory Diversity Issues: Math, Science, Engineering |

| VA | George Mason University | Social-Justice Education Critical Race Studies Social-Justice Narratives |

| WV | Fairmont State University | Principles of Race, Class, and Gender |

| WA | Eastern Washington University | Introduction to Gender, Women’s, and Sexuality Studies Introduction to LGBTQ+ Studies Gender, Representation, and Popular Culture |

| WI | University of Wisconsin–Madison | Latinx Feminisms: Women’s Lives, Work, and Activism Education and White Supremacy Asian American Feminist and Queer Cultural Productions |

| WY | University of Wyoming | Queer Theory Gender, Race, Sex, and Social Systems Rhetorics for Social Justice |

Methodology

Florida

I obtained information from the October 3, 2024, Board Book from the University of Florida Board of Trustees, which was submitted to the state for review, and the approved courses for the 2025–26 academic year, available on the Florida Board of Governors website. I compared the courses from the board book, representing courses before review, and those on the Board of Governors website, representing the final approved courses. Field categories such as humanities and math were determined by the state.

University of Arizona and the College of Charleston

I obtained the approved general education course lists for 2025 from each college’s website. Duplicate course titles were eliminated so that the analysis reflected only unique courses. For organizational purposes, courses were categorized into three broad groups: STEM, humanities, and social sciences.

To determine whether a course emphasized race, identity, or progressive activism, I relied on official course titles and descriptions. Certain words and phrases often served as indicators—e.g.,“activism,” “social justice,”“critical theory,”“race, equity, and inclusion.” Courses that were primarily descriptive of cultures or languages were excluded unless they explicitly framed the material around activism or identity-based analysis. The presence of a keyword alone was not sufficient to include a course. For example, if a course mentioned Marxism only as part of a survey of philosophical thought, it was not coded as activist. Titles and descriptions were reviewed in full to assess whether the course was framed in an activist, identity-centered, or advocacy-oriented way. Only courses with obvious ideological framings were included. In cases where course titles and descriptions were too vague to determine whether the class emphasized race, identity, or activism, these courses were excluded from the count. As a result, the analysis is limited to courses where the ideological framing was apparent from the title and description.

Endnotes

Photo: SDI Productions / E+ via Getty Images

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).